History of Chennai

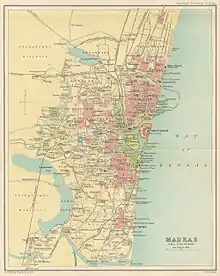

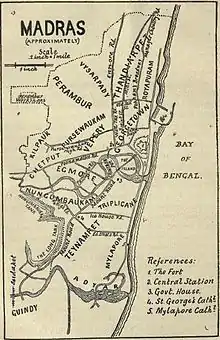

Chennai, formerly known as Madras, is the capital of the state of Tamil Nadu and is India's fifth largest city.[1] It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. With an estimated population of 8.9 million (2014), the 383-year-old city is the 31st largest metropolitan area in the world.

Chennai boasts a long history from the English East India Company, through the British rule to its evolution in the late 20th century as a services and manufacturing hub for India. Additionally, the pre-city area of Chennai has a long history within the records of South Indian Empires.

Ancient area in South India

Chennai, originally known as "Madras", was located in the province of Tondaimandalam, an area lying between Penna River of Nellore and the Ponnaiyar river of Cuddalore. Before this region was ruled by early Cholas during the 1st century CE. The capital of the province was Kancheepuram. The name Madras was Derived from Madrasan a fisherman head who lived in coastal area of Madras. The Original Name of Madras Is Puliyur kottam which is 2000 year old Tamil ancient name. Tondaimandalam was ruled in the 2nd century CE by Tondaiman Ilam Tiraiyan who was a representative of the Chola family at Kanchipuram. The modern city of "Chennai" arose from the British settlement of Fort St. George and its subsequent expansion through merging numerous native villages and European settlements around Fort St. George into the city of Madras. While most of the original city of Madras was built and settled by Europeans, the surrounding area which was later incorporated included the native temples of Thiruvanmiyur, Thiruvotriyur, Thiruvallikeni (Triplicane), and Thirumayilai (Mylapore) which have existed for more than 2000 years. Thiruvanmiyur, Thiruvotriyur, and Thirumayilai are mentioned in the Thevarams of the Moovar (of the Nayanmars) while Thiruvallikeni in the Nalayira Divya Prabhandhams (of the Alwars).

Chola and Pallava eras

Subsequent to Ilam Tiraiyan, the region was ruled by the Chola Prince Ilam Killi. The Chola occupation of Tondaimandalam was put to an end by the Andhra Satavahana incursions from the north under their King Pulumayi II. They appointed chieftains to look after the Kanchipuram region. Bappaswami, who is considered as the ruler to rule from Kanchipuram, was himself a chieftain (of the tract around) at Kanchipuram under the Satavahana empire in the beginning of the 3rd century. The Pallavas who had so far been merely viceroys, then became independent rulers of Kanchipuram and its surrounding areas.

The Pallavas held sway over this region from the beginning of the 3rd century to the closing years of the 9th century, except for the interval of some decades when the region was under the Kalabhras. The Pallavas were defeated by the Cholas under Aditya I by about 879 and the region was brought under the Chola rule. The Pandyas under Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan rose to power and the region was brought under the Pandya rule by putting an end to Chola supremacy in 1264.

Historical establishment of the city

Under Vijayanagara Dynasty Nayaks

The present-day city of Chennai started in 1644 as an English settlement known as Fort St. George. The region was then a part of the Vijayanagara Empire, then headquartered at Chandragiri in present-day Andhra Pradesh. The Vijayanagar rulers who controlled the area, appointed chieftains known as Nayaks who ruled over the different regions of the province almost independently. The region was under the control of the Damerla Venkatadri Nayakar, a Padma Velama Nayak chieftain of Srikalahasti and Vandavasi. He was also an influential Nayak ruler under the Vijayanagara King Peda Venkata Raya then based in Chandragiri-Vellore Fort, was in-charge of the area of present Chennai city when the English East India Company arrived to establish a factory in the area.[2][3]

Obtaining the Land Grant

On 20 August 1639, Francis Day of the East India Company along with Damerla Venkatadri Naick traveled to Chandragiri palace to meet the Vijayanagara King Peda Venkata Raya and to obtain a grant for a small strip of land in the Coromandel Coast from in Chandragiri as a place to build a factory and warehouse for their trading activities. It was from Damarla Venkatadri Naick domain, on 22 August 1639, the piece of land lying between the river Cooum almost at the point it enters the sea and another river known as the Egmore river was granted to East India Company after deed from Vijaynagara emperor.

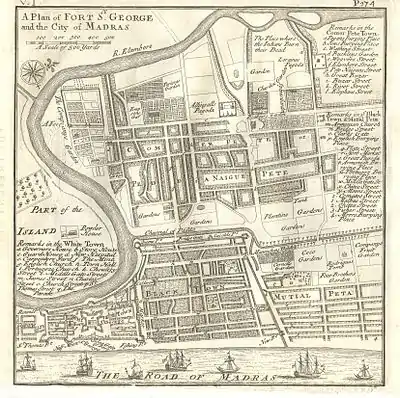

On this piece of wasteland was founded Fort St. George, a fortified settlement of British merchants, factory workers, and other colonial settlers. Upon this settlement, the English expanded their colony to include a number of other European communities, new British settlements, and various native villages, one of which was named Mudhirasa pattanam. It in honor of the later village upon which the British named the entire colony and the combined city Madras. Controversially, in an attempt to revise history and justify renaming the city as Chennai, the ruling party has purged the history of the early English Madras settlements. According to the new party history, instead of being named Madras, it was named Chennai, after a village called Chennapattanam, in honour of Damarla Chennapa Naick, father of Damerla Venkatadri Naick, who controlled the entire coastal country from Pulicat in the north to the Portuguese settlement of Santhome.[3][4]

However, it is widely recorded that while the official center of the present settlement was designated Fort St. George, the British applied the name Madras to a new large city which had grown up around the Fort including the "White Town" consisting principally of British settlers, and "Black Town" consisting of principally Catholic Europeans and allied Indian minorities.

Early European settlers

Modern Chennai traces its roots to its early days as a trading hub with a history influenced by various foreign powers. The city's initial growth was closely linked to its role as an artificial harbor and trade center. In 1522, the Portuguese arrived and constructed a port, which they named São Tomé in honor of Saint Thomas, believed to have preached in the region between 52 and 70 AD. They also undertook the restoration of the Nestorian church in Mylapore and the renovation of Saint Thomas's tomb.

Subsequently, the region fell under Dutch control, with their establishment near Pulicat, just north of the city, in 1612. Both the Portuguese and the Dutch aimed to expand their colonial populations, but even with a combined population of 10,000 people by the time the British arrived, they remained outnumbered by the local Indian population.

Arrival of the English

By 1612, the Dutch established themselves in Pulicat to the north. In the 17th century, the English East India Company decided to build a factory on the east coast and in 1626 selected its site as Armagon (Dugarazpatnam), a village some 35 miles north of Pulicat. The calico cloth from the local area, which was in high demand, was of poor quality and not suitable for export to Europe. The English soon realized that the port Armagon was unsuitable for trade purposes. Francis Day, one of the officers of the company, who was then a Member of the Masulipatam Council and the Chief of the Armagon Factory, made a voyage of exploration in 1637 down the coast as far as Pondicherry with a view to choosing a site for a new settlement.

Permission from Vijayanagara Rulers

At that time the Coromandel Coast was ruled by Peda Venkata Raya, from the Aravidu Dynasty of Vijayanagara Empire based out of Chandragiri-Vellore. Under the Kings, local chiefs or governors known as Nayaks ruled over each district.

Damarla Venkatadri Naick, the local governor of the Vijayanagar Empire and Nayaka of Wandiwash (Vandavasi), ruled the coastal part of the region, from Pulicat to the Portuguese settlement of San Thome. He had his headquarters at Wandiwash, and his brother Ayyappa Naickresided at Poonamallee, a few miles to the west of Madras, where he looked after the affairs of the coast. Beri Thimmappa, Francis Day's dubash (interpreter), was a close friend of Damarla Ayyappa Naick. In the early 17th century Beri Thimmappa of the Puragiri Kshatriya (Perike) caste migrated to the locality from Palacole, near Machilipatnam in Andhra Pradesh.[5] Ayyappa Naick persuaded his brother to lease the sandy strip to Francis Day and promised him trade benefits, army protection, and Persian horses in return. Francis Day wrote to his headquarters at Masulipatam for permission to inspect the proposed site at Madraspatnam and to examine the possibilities of trade there. Madraspatnam seemed favorable during the inspection, and the calicoes woven there were much cheaper than those at Armagon (Durgarazpatam).

On 22 August 1639, Francis Day secured the Grant by the Damarla Venkatadri Nayakadu, Nayaka of Wandiwash, giving over to the East India Company a three-mile-long strip of land, a fishing village called Madraspatnam, copies of which were endorsed by Andrew Cogan, the Chief of the Masulipatam Factory, and are even now preserved. The Grant was for a period of two years and empowered the company to build a fort and castle on about five square kilometers of its strip of land.[6]

The English Factors at Masulipatam were satisfied with Francis Day's work. They requested Day and the Damarla Venkatadri Nayakadu to wait until the sanction of the superior English Presidency of Bantam in Java could be obtained for their action. The main difficulty, among the English those days, was a lack of money. In February 1640, Day and Cogan, accompanied by a few factors and writers, a garrison of about twenty-five European soldiers and a few other European artificers, besides a Hindu powder-maker named Naga Battan, proceeded to the land which had been granted and started a new English factory there. They reached Madraspatnam on 20 February 1640; and this date is important because it marks the first actual settlement of the English at the place.

Grant establishing lawful self-rule

The grant signed between Damarla Venkatadri and the English had to be authenticated or confirmed by the Raja of Chandragiri - Venkatapathy Rayulu. The Raja, Venkatapathy Rayulu, was succeeded by his nephew Sri Rangarayulu in 1642, and Sir Francis Day was succeeded by Thomas Ivy. The grant expired, and Ivy sent Factor Greenhill on a mission to Chandragiri to meet the new Raja and to get the grant renewed. A new grant was issued, copies of which are still available. It is dated October - November 1645. This new grant is important regarding the legal and civic development of the English settlement. Because the Raja operated an arbitrary and capricious legal code which fundamentally discriminated against private property, trade, and merchandising in general, and against non-Indians in particular, the new grant signed in 1645 expanded the rights of the English by empowering them to administer English Common Law amongst their colonists and Civil Law between the colonists and the other European, Muslim, and Hindu nationalities. Furthermore, it expanded the Company property by attaching an additional piece of land known as the Narimedu (or 'Jackal-ground') which lay to the west of the village of Madraspatnam. This new grant laid the foundation for the expansion of Madras into its present form. All three grants are said to have been engraved on gold plates which were later reported to have been plundered, disappearing during one of the genocides of the English colony. However, there are city records of their existence long afterward, and it has been suggested that the present government may still hold them.

Expansion of Fort St. George into Madras

Francis Day and his superior Andrew Cogan can be considered as the founders of Madras (now Chennai). They began construction of the Fort St George on 23 April 1640 and houses for their residence. Their small fortified settlement quickly attracted other East Indian traders and as the Dutch position collapsed under hostile Indian power they also slowly joined the settlement. By 1646, the settlement had reached 19,000 persons and with the Portuguese and Dutch populations at their forts substantially more. To further consolidate their position, the Company combined the various settlements around an expanded Fort St. George, which including its citadel also included a larger outside area surrounded by an additional wall. This area became the Fort St. George settlement. As stipulated by the Treaty signed with the Nayak, the British and other Christian Europeans were not allowed to decorate the outside of their buildings in any other color but white. As a result, over time, the area came to be known as 'White Town'.

According to the treaty, only Europeans, principally Protestant British settlers were allowed to live in this area as outside of this confine, non-Indians were not allowed to own property. However, other national groups, chiefly FrenchPortuguese, and other Catholic merchants had separate agreements with the Nayak which allowed them in turn to establish trading posts, factories, and warehouses. As the East India Company controlled the trade in the area, these non-British merchants established agreements with the company for settling on Company land near "White Town" per agreements with the Nayak. Over time, Indians also arrived in ever greater numbers and soon, the Portuguese and other non-Protestant Christian Europeans were outnumbered. Following several outbreaks of violence by various Hindu and Muslim Indian communities against the Christian Europeans, White Town's defenses and its territorial charter was expanded to incorporate most of the area which had grown up around its walls thereby incorporating most of its Catholic European settlements. In turn they resettled the non-European merchants and their families and workers, almost entirely Muslim or of various Hindu castes outside of the newly expanded "White Town". This was also surrounded by a wall. To differentiate these non-European and non-Christian area from "White Town", the new settlement was termed "Black Town. Collectively, the original Fort St. George settlement, "White Town", and "Black Town" were called Madras.

During the course of the late 17th century, both plague and genocidal warfare reduced the population of the colony dramatically. Each time, the survivors fell back upon the safety of the Fort St George. As a result, owing to the frequency of outbursts of racial and national violence against the Europeans and especially the English, Fort St George with its impressive fortifications became the nucleus around which the city grew and rebuilt itself. Several times throughout the life of the colony, the Fort became the last refuge of Europeans and their allied Indian communities due to raids by several Indian rulers and powers, which resulted in the almost total destruction of the town. Each time the town and later city was rebuilt and repopulated with new English and European settlers. The Fort still stands today, and a part of it is used to house the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly and the Office of the Chief Minister. Elihu Yale, after whom Yale University is named, was British governor of Madras for five years. Part of the fortune that he amassed in Madras as part of the colonial administration became the financial foundation for Yale University.

The city has changed its boundaries as well as the geographic limits of its quarters several times, principally as a result of raids by surrounding Hindu and Muslim powers. For instance, Golkonda forces under General Mir Jumla conquered Madras in 1646, massacred or sold into slavery many of the Christian European inhabitants and their allied Indian communities, and brought Madras and its immediate surroundings under his control. Nonetheless, the Fort and its surrounding walls remained under British control who slowly rebuilt their colony with additional colonists despite another mass murder of Europeans in Black Town by anti-colonialists agitated by Golkonda and plague in the 1670s. In 1674, the expanded colony had nearly 50,000 mostly British and European colonists and was granted its own corporate charter, thereby officially establishing the modern day city. Eventually, after additional provocations from Golkonda, the British pushed back until they defeated him.

After the fall of Golkonda in 1687, the region came under the rule of the Mughal Emperors of Delhi who in turn granted new Charters and territorial borders for the area. Subsequently, firmans were issued by the Mughal Emperor granting the rights of the English East India company in Madras and formally ending the official capacity of local rulers to attack the British. In the latter part of the 17th century, Madras steadily progressed during the period of the East India Company and under many Governors. Although most of the original Portuguese, Dutch, and British population had been killed during genocides during the Golkonda period, under Moghul protection, large numbers of British and Anglo-American settlers arrived to replenish these losses. As a result, during the Governorship of Elihu Yale (1687–92), the large number of British and European settlers led to the most important political event which was the formation of the institution of a mayor and the Corporation for the city of Madras. Under this Charter, the British and Protestant inhabitants were granted the rights of self-government and independence from company law. In 1693, a perwanna was received from the local Nawab granting the towns of Tondiarpet, Purasawalkam and Egmore to the company which continued to rule from Fort St. George. The present parts of Chennai like Poonamalee (ancient Tamil name - Poo Iruntha valli), Triplicane (ancient Tamil name - Thiru alli keni) are mentioned in Tamil bhakti literature of the 6th - 9th centuries.Thomas Pitt became the Governor of Madras in 1698 and governed for eleven years. This period witnessed remarkable development of trade and increase in wealth resulting in the building of many fine houses, mansions, housing developments, an expanded port and city complete with new city walls, and various churches and schools for the British colonists and missionary schools for the local Indian population.

_(14581822508).jpg.webp)

Acquisitions

| Village | Year |

|---|---|

| Madraspatnam | 1639 |

| Narimedu (area to the west of Madraspatnam) | 1645 |

| Triplicane | 1672 |

| Tiruvottiyur | 1708 |

| Kottivakkam | 1708 |

| Nungambakkam | 1708 |

| Egmore | 1720 |

| Purasawalkam | 1720 |

| Tondiarpet | 1720 |

| Chintadripet | 1735 |

| Vepery | 1742 |

| Mylapore | 1749 |

| Chennapatnam | 1801 |

1750s to the end of the British Raj

In 1746, Fort St George and Madras were captured at last. But this time it was by the French under General La Bourdonnais, who used to be the Governor of Mauritius. Because of its importance to the East India Company, the French plundered and destroyed the village of Chepauk and Blacktown, the locality across from the port where all the dockyard labourers used to live.[7]

The British regained control in 1749 through the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. They then strengthened and expanded Fort St George over the next thirty years to bear subsequent attacks, the strongest of which came from the French (1759, under Thomas Arthur, Comte de Lally), and later Hyder Ali, the Sultan of Mysore in 1767 during the First Anglo-Mysore War. Following the Treaty of Madras which brought that war to an end, the external threats to Madras significantly decreased. The 1783 version of Fort St George is what still stands today.

In the latter half of the 18th century, Madras became an important British naval base, and the administrative centre of the growing British dominions in southern India. The British fought with various European powers, notably the French at Vandavasi (Wandiwash) in 1760, where de Lally was defeated by Sir Eyre Coote, and the Danish at Tharangambadi (Tranquebar). Following the British victory in the Seven Years' War they eventually dominated, driving the French, the Dutch and the Danes away entirely, and reducing the French dominions in India to four tiny coastal enclaves. The British also fought four wars with the Kingdom of Mysore under Hyder Ali and later his son Tipu Sultan, which led to their eventual domination of India's south. Madras was the capital of the Madras Presidency, also called Madras Province.

By the end of 1783, the great 18th century wars which saw the British and French battle from Europe to North America and from the Mediterranean to India, resulted in the British being in complete control of the city's regional and most of South India area. Although the British had lost most of their well-populated, industrious, and wealthy North American colonies, after a decade's feud with the French, they were securely in control of Madras and most of the Indian trade. Consequently, they expanded the Chartered control of the company by encompassing the neighbouring villages of Triplicane, Egmore, Purasawalkam and Chetput to form the city of Chennapatnam, as it was called by locals then. This new area saw a proliferation of English merchant and planter families who, allied with their wealthy Indian counterparts, jointly controlled Chennapatnam under the supervision of White Town. Over time and administrative reforms, the area was finally fully incorporated into the new metropolitan charter of Madras.

The development of a harbour in Madras led the city to become an important centre for trade between India and Europe in the 18th century. In 1788, Thomas Parry arrived in Madras as a free merchant and he set up one of the oldest mercantile companies in the city and one of the oldest in the country (EID Parry). John Binny came to Madras in 1797 and he established the textile company Binny & Co in 1814. Spencer's started as a small business in 1864 and went on to become the biggest department stores in Asia at the time. The original building which housed Spencer & Co. was burnt down in a fire in 1983 and the present structure houses one of the largest shopping malls in India, Spencer Plaza. Other prominent companies in the city included Gordon Woodroffe, Best & Crompton, Higginbotham's, Hoe & Co and P. Orr & Sons.

Millions of people starved to death throughout British ruled Tamil Nadu, around 3.9 million people perished in Chennai alone within two years of 1877–78.[8]

Madras was the capital of the Madras Presidency and thus became home to important commercial organisations. Breaking with the tradition of the closed and almost wholly British controlled system of the English East India Company, The Madras Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1836 by Fredrick Adam, Governor of the Madras Presidency (the second oldest Chamber of Commerce in the country). Thereafter in a nod to the declining fortunes of the British textile owners and skilled workers who were still extant in the city, the Madras Trades Association was established in 1856, by which the old colonial families still involved in the skilled and textile trades were granted entry into the British and Indian financial trade system. The Madras Stock Exchange was established in 1920. In 1906, the city experienced a financial crisis with the failure of its leading merchant bank, Arbuthnot & Co. The crisis also imperilled Parry & Co and Binny & Co, but both found rescuers. The lawyer V. Krishnaswamy Iyer made a name for himself representing claimants, mostly wealthy Hindus and Muslims who had lent money on the failed bank. The next year, flush with funds won from the original British owners who had capitalized the bank, he organized a group of Chettiar merchants to found Indian Bank, with which he funded new Indian enterprises and broke into the previously closed ranks of the British financial system. The bank still has its corporate headquarters in the city.

During World War I, Madras (Chennai) was shelled by the German light cruiser SMS Emden, causing 5 civilian deaths and 26 wounded.

Since independence in 1947

After India became independent in 1947, the city became the administrative and legislative capital of Madras State, which was renamed as Tamil Nadu in 1968.

During the reorganisation of states in India on linguistic lines, in 1953, Telugu speakers wanted Madras as the capital of Andhra Pradesh[9] and coined the slogan "Madras Manade" (Madras is ours). The demands for the immediate creation of a Telugu-speaking state were met with after Tirupati was included in Andhra State and after the leaders who led the movement were convinced to give up their claim on Madras.[10] The dispute arose as over the preceding hundred years the early British, European workers and small cottage capitalists had been replaced in large part by both Tamil- and Telugu-speaking people. In fact, as the greater concentration of capital wrecked what remained of the old East Indian middle class, the city principally became a large housing development for huge numbers of workers. Most of these were recruited as cheap labor from the relatively poor Telugu speakers, which enraged the Tamil nationals who were originally the working- and middle-class settlers of Madras in the late 18th century. Earlier, Panagal Raja, Chief Minister of Madras Presidency in the early 1920s had suggested that the Cooum River be the boundary between the Tamil and Telugu administrative areas.[11] In 1953, the political and administrative dominance of Tamils, both at the Union and State levels ensured that Madras was not transferred to the new state of Andhra.

Although the original inhabitants of Madras and responsible for its growth into the modern metropolis of today, virtually no British or European nationals remain. Always a tiny minority in comparison with the vast Indian population of the hinterlands, despite slow growth in natural birthrate and continued settlement, the British and Europeans became an ever-decreasing share of their cities' populations. As more and more Indians arrived from the countryside to work in the city, the British and other Europeans found it increasingly difficult to establish or maintain independent wealth as they had during the early East Indian regime. Hundreds of thousands had come to India between about 1600 and 1770, and another million had come between 1770 and 1870. These settlers and their families spread throughout India or settled in the cities, with Madras being one of their principal entry points. However, by the early 20th century they had become a small minority in the city. Although they remained in control of the original corporations and businesses of Madras, and were the official representatives of the imperial government, as a minority they would not survive a democratic form of government with the larger Indian population in Madras represented. Thus happened with the Independence of India in 1947.

Despite undergoing significant demographic shifts after independence, the enduring remnants of the original British community, alongside other minority groups and the rich tapestry of British cultural influences, contribute to the cosmopolitan character of the city now known as Chennai. In days gone by, the populations of Telugu and Tamils were fairly balanced, but post-independence, the dynamics of the city underwent rapid changes.

Today, Chennai is home to a diverse mix of people, including mixed Anglo-Indian descendants of the early English settlers, a smaller yet still present British and European community, and migrant Malayalee communities. The city's status as a vital administrative and commercial hub has attracted people from various corners of India, such as Bengalis, Punjabis, Gujaratis, Marwaris, as well as residents from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, all of whom have enriched its cosmopolitan fabric.

Chennai also has a growing expatriate population, particularly from the United States, Europe, and East Asia, who find employment opportunities in the city's burgeoning industries and IT sectors.

Since its establishment as a city in 1639, English was the official language of the city. However, from the 1960s, the central government started gearing up the use of Hindi in business and government. In response, from 1965 to 1967 the city saw agitation against the two-language (Hindi and local language) policy, and there was sporadic rioting. Madras witnessed further political violence due to the civil war in Sri Lanka, with 33 people killed by a bomb planted by the Tamil Eelam Army at the airport in 1984, and assassination of thirteen members of the EPRLF and two Indian civilians by the rival LTTE in 1991. In the same year, former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated in Sriperumbudur, a small town close to Chennai, whilst campaigning in Tamil Nadu, by Thenmuli Rajaratnam A.K.A. Dhanu, widely believed to have been an LTTE member. In 1996, in keeping with the recent nationwide practice of Indianizing city names, the Government of Tamil Nadu, then represented by Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, renamed the city to Chennai. The 2004 tsunami lashed the shores of Chennai killing many.

Chennai is now a large cultural, commercial and industrial centre, known for its cultural heritage and temple architecture. Chennai is the automobile capital of India, with around forty percent of the automobile industry having a base there and with a major portion of the nation's vehicles being produced there. It is a major manufacturing centre. Chennai has also become a major centre for outsourced IT and financial services from the Western world. Owing to the city's rich musical and cultural traditions, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has included Chennai in its Creative Cities Network.[12]

Name

Various etymologies have been posited for the name, Chennai or Chennapattanam. A popular explanation is that the name comes from the name of Damarla Chennappa Naick, Nayaka of Chandragiri and Vandavasi, father of Damarla Venkatadri Naick, from whom the English acquired the town in 1639. The first official use of the name Chennai is said to be in a sale deed, dated 8 August 1639, to Francis Day of the East India Company.[13]

Chennai's earlier name of Madras is similarly mired in controversy. But there is some consensus that it is an abbreviation of Madraspatnam, the site chosen by the British East India Company for a permanent settlement in 1639.[14]

Currently, the nomenclature of the area is in a state of controversy. The region was often called by different names as madrapupatnam, madras kuppam, madraspatnam, madarasanpatnam, Perumparaicheri, and madirazpatnam as adopted by locals. Another small town, Chennapatnam, lay to the south of it. This place was supposedly named so by Damarla Venkatadri Naick, Nayak of Vandavasi in remembrance of his father Damarla Chennappa Naick. He was the local governor for the last Raja of Chandragiri, Sri Ranga Raya VI of Vijayanagar Empire. The first Grant of Damarla Venkatadri Naick makes mention of the village of Madraspatnam as incorporated into East India lands but not of Chennapatnam. This together with the written records makes it clear that the Fort which became the centre of present Chennai, was built upon or nearby the village of Madraspatnam. Although, Madraspatnam is named in later records following the establishment of Fort St. George, this is likely because of the discriminatory nature of the local caste system. Under Hindu caste code, as well as English Common Law, it is unlikely that Fort St. George was built upon the village of Madraspatnam and its inhabitants incorporated into the new town. Instead, it is likely that Fort was built either close to the village or if it was built upon the village, the village was relocated. In fact, in all records of the times, a difference is made between the original village of Madraspatnam and the new town growing around the Fort known as "White Town". Therefore, because of the fort's proximity or origin to the village of Mandraspatnam, and the fort's centrality to the development of the city, the British settlers of the city later named their settlement Madras in honour of it. Further militating against the name "Chennai", Chennapatnam was the name in later years of an area explicitly detailed as having been incorporated of native villages, European plantations, and European merchant houses outside of the combined city of Madras consisting of Fort St. George, and White and Black Town. Lastly, while the Fort St. George, White Town, and Black Town areas were fully incorporated together by the late 18th century, and was known as Madras, Chennapatnam was its own separate entity existing under the authority of Fort St. George well into the 19th century. Consequently, once the area separating Chennapatnam and Old Madras was built over uniting the two settlements, as founders, settlers, and authorities of area, the English named the new united city Madras. Thus it is improbable that the area was ever called Chennai. Instead, being the gateway of trade and the centre of the economy of the region, the English settlement and their fort of 1639–40, which was the basis for the presently named city of Chennai, was likely called Madras as well by the rest of India. The DMK renamed Madras to Chennai as DMK founder Anna renamed Madras State as Tamil Nadu.

References

- "Chennai". lifeinchennai.com. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- "District profile - Chennai district administration- official website". Chennai.tn.nic.in. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- C S Srinivasachari (1939). History of the City of Madras. P_Varadachary_And_co. pp. 63–69.

- "District profile - Chennai district administration- official website". Chennai.tn.nic.in. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- The Madras Tercentenary commemoration volume, Volume 1939

- S. Muthiah (21 August 2006). "Founders' Day, Madras". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 27 February 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- http://www.chennaicorporation.com/madras_history.htm Chennai Corporation - Madras History

- Michael Allaby (2005). India. p. 22. ISBN 9780237527556.

- Narayana Rao, K. V. (1973). The emergence of Andhra Pradesh. Popular Prakashan. pp. 227. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- A. R, Venkatachalapathy; Aravindan, Ramu (2006). "How Chennai Remained with Tamil Nadu". Chennai not Madras: perspectives on the city. Marg Publications on behalf of the National Centre for the Performing Arts. p. 9. ISBN 9788185026749. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- G. V. Subba Rao (1982). History of Andhra movement. Committee of History of Andhra Movement. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- "Chennai gets Unesco recognition for music". Business Standard India. 8 November 2017.

- "District Profile – Chennai". District Administration, Chennai. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Origin of the Name Madras". Corporation of Madras.

Bibliography

- Muthiah, S. (2004). Madras Rediscovered. East West Books (Madras) Pvt Ltd. ISBN 81-88661-24-4.

- Wheeler, J. Talboys (1861). Madras in the Olden Time, Vol II 1639-1702. Madras: J. Higginbotham.

- Wheeler, J. Talboys (1862). Madras in the Olden Time, Vol II 1702-1727. Madras: J. Higginbotham.

- Wheeler, J. Talboys (1862). Madras in the Olden Time, Vol III 1727-1748. Madras: J. Higginbotham.

- S. Srinivasachari, Dewan Bahadur Chidambaram (1939). History of the City of Madras: Written for the Tercentenary Celebration Committee, 1939. Madras: P. Varadachary & Co.

- Hunter, W. W. (1886). The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Volume IX, Second Edition. London: Trubner & Co.

- Barlow, Glynn (1921). The Story of Madras. Oxford University Press.

- Love, Henry Davidson (1913). Vestiges of Old Madras, 1640-1800 : traced from the East India Company's records preserved at Fort St. George and the India Office and from other sources. London: Murray.

- Somerset, Playne Wright (1915). Southern India: its history, people, commerce, and industrial resources. London: The Foreign and Colonial Compiling and Publishing Co.. Chapter: The City of Madras and Environs Preview in Google books