Mads Johansen Lange

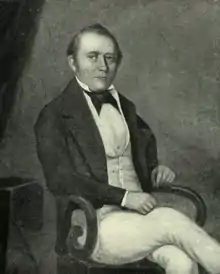

Mads Johansen Lange, nicknamed the King of Bali (18 September 1807 in Rudkøbing, Denmark – 13 May 1856 in Kuta, Bali, Indonesia), was a Danish trader, entrepreneur, peace maker on Bali, knight of the Order of the Netherlands Lion, and recipient of the Danish gold medal of achievement. He was the son of Lorents Lange Pedersen[lower-alpha 1] and Maren Lange, a merchant and a merchant's daughter, respectively.[1]

Mads Johansen Lange | |

|---|---|

Painted by unknown Chinese painter on Bali | |

| Born | 18 September 1807 Rudkøbing, Denmark |

| Died | 13 May 1856 (aged 48) |

| Resting place | Kuta, Bali, Indonesia (then Kotta) |

| Other names | King of Bali |

| Title | Knight of the Order of the Netherlands Lion |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Sultan Ibrahim, the Sultan of Johor (grandson) |

| Awards | Danish gold medal of achievement |

| Signature | |

| |

Lange travelled to the Dutch East Indies at an early age and settled on the island of Bali. Here he built a thriving commercial enterprise, exporting rice, spices and beef, and importing weapons and textiles. He maintained good relations with the local Rajas and mediated between them and the Dutch colonists with great success.

Lange died 48 years old, possibly because of poisoning. His business had been in decline by then, and even the joint efforts of his brother and nephew could not change this. The remains of the business were sold to a Chinese merchant. He had three children with local Balinese women (the Raja of Tabanan's daughter and a Chinese woman).[2] His daughter Cecilia married into Johore royalty and bore a son, Ibrahim, who became the Sultan of Johor. Lange is buried in Kotta (now 'Kuta').

Early life

Childhood

Mads Lange was born in Rudkøbing on 18 September 1807, as the second son of Lorents Lange and Maren Hansen. He had one sister and ten brothers, three of whom were children from an earlier marriage of his mother. The youngest brother died when he was six years old. Little else is known about Mads' childhood.[3]

Ancestors

His father, Lorents Lange Pedersen, was the son of master builder Peder Frandsen Knudsøn and Johanne Margrethe Lorentzdatter Lange. He was the only one of his nine brothers and sisters to take his mother's surname, Lange, as his baptismal name. Although the idea was for it to be a middle name, in practice it became his surname, meaning his mother's surname lived on through him. Lorents was the only boy among the three children who survived into adulthood. In later life Lorents was a member of the Langeland militia. He had an indirect role in the Napoleonic Wars: Spanish soldiers were billeted in his house from 1812 to 1813. He received 4 florins a month for this, but it meant his family home was now occupied by about fifteen people. This was surely a contributing factor in his decision to buy a new house on the Østergade, No. 12–14, in 1816. In 1822 Lorents started a transport company with a mail coach and two horses, not uncommon for a merchant in those days. His cousin was master of the ferry services, which probably benefited the small company enormously. Lorents died in 1828.

Lange's mother, Maren Hansen, had married Mads Andresen in 1799. With him she had three sons. Mads Andresen died in 1805, and later that year Maren married Lorents Lange. She had inherited a tavern and a shop, which Lorents ran even though he had been trained to be a master builder. After Lorents' death she married Mads Hansen.[1]

Career at sea

Lange started his career at sea at fourteen years of age. Three years later, in 1824, he worked aboard the ship North, where he met Captain John Burd. They sailed together for many years, including to the Danish trading post Tranquebar in India. In 1833 they returned to Denmark, and Mads seized this opportunity to visit his parents' home. He remained in Denmark for some time and was counted in the 1834 census.

In the meantime, Burd sold the ship North in Hamburg. A little while later he and Lange bought the ship South, which they steered towards India and China. Burd was the captain and Lange the first mate. With them traveled Lange's three brothers: Hans, Carl Emil, and Hans Henrik, 20, 18, and 14 years old, respectively. None of the four brothers would ever return to Denmark.[4]

Settlement in the East

Lombok

In 1835 Mads decided to settle on the island of Lombok, east of Bali and Java, because here there was a lively commercial traffic. The island contained two princely states, Karangasem Lombok and Mataram. The first was the largest, and it was the Raja from this state who allowed Lange to trade from the port city of Tanjungkarang, in exchange for a yearly fee. It was here that Lange created his first flourishing commercial enterprise. He exported coffee, rice, spices and green tobacco, importing textiles and weapons that could easily be sold to the local warring tribes.[5]

In 1839 fights erupted ever more frequently between the princely states. Combined with increased Dutch efforts to colonize the island, this forced Mads to leave Lombok. When the Raja who had supported him was defeated, Mads had to flee to Bali head-over-heels in his schooner Venus.[6]

Bali

Lange now had to start over on Bali. He settled on the south coast of the island, near the town of Kotta. The town was situated on a narrow peninsula, which made it possible to load goods on the east and the west side. This came in very handy during the monsoon season, when winds abruptly changed direction.

Four factors helped Lange settle on Bali successfully. First was his long history of trading with Bali. This meant he knew the possibilities this island had to offer. Second were his good relations with the Balinese Rajas. Raja Kassiman of Badung had even invited him to settle on the island. This meant he enjoyed protection and could obtain cheap labour, but probably also that he possessed a monopoly on trade on the island. The third factor was that the local population on Bali was suffering from an economic depression, after a war with Java that had made the export of slaves impossible. The fourth factor was a shortage of rice in Asia. Bali was well situated to reap the benefits of this shortage because the island population was well skilled in rice farming, and because the climate was such that it allowed for up to three harvests a year.[7][6]

Lange built his factorij at Kotta and steadily expanded it with residential units and warehouses. The Dutch nobleman and politician Wolter Robert, Baron van Hoevell visited Bali and Mads Lange, and gave a description of the factorij:[8]

A large stone wall was the first thing that caught our eye. Through a large door or gate, which was locked at night, we rode into the estate. Opposite the gate stands a cannon with the mouth in the direction of the gate as a warning in case of enemy attacks. It proved that mister Lange did not blindly entrust his well-being to Raja of the country in which he was residing, and that vigilance and a gun in hand were better to rely on.

Inside this wall are the buildings that form mister Lange's house (…). Here beauty is sacrificed for usefulness. The central building consists of several good guest rooms which, as I was told, left nothing to be desired.

In the foreground ones gaze is drawn towards a large Pandopo which is used for receiving Balinese come to talk about trade. There is almost never any place for visitors. You could describe it as a stock exchange which never closes. There are also a special dining room and a billiards room, which are very well equipped, and in which the generous host made sure his guests were wanting nothing.

Next to the main building are several houses for the staff and very good, spacious warehouses. Even in this there was an intense and uninterrupted bustle. Continuously rice was being brought in by the Balinese, in exchange for cash or other goods they came to acquire. Through the creative force of mister Lange, a sort of colony has steadily grown within those walls, a lively and densly occupied city, which possesses order, dynamism and prosperity.

— Van Hoëvell

Lange was in good standing with the Balinese, and within a few years he had built a flourishing company with about fifteen ships, plying lively trade among ports in the East Indies, the West Indies, and Europe. His brothers helped him out in the factorij, and sometimes sailed on the ships when trading missions were difficult or demanding. Pirates and bad weather conditions often made these journeys dangerous. Two of Lange's brothers, Hans Henrik and Carl Emil, died during these kinds of journeys, the latter dying in plain sight of Mads when the rowboat he was in capsized.[9][10]

Lange's career as a merchant blossomed during the 1840s. Halfway through that period his fleet of ships was capable of transporting between 800 and 1500 tons of freight. Many of the ships were newly built, probably in Singapore, a city Mads often visited. Coconut oil was sold in Singapore in great quantities, yielding profits of 200 to 300%. Because of this, Mads had an oil mill imported entire from Europe. This was an expensive operation, but the costs were recuperated within a few years. Rice kept being announced for low prices in the newspapers of Singapore, Australia and China.[11][12]

From 1841 to 1843 Lange had an intimate relationship with his second cousin Malana von Munk, who was a distant relative of Christian IX of Denmark. While the relationship was strong and there are writings describing Lange's infatuation with von Munk, she had to return to Denmark due to personal reasons, bringing the two-year relationship to an end.

Predominantly French ships sailed to Kotta to load trading goods, especially cattle, ponies, pigs and poultry. Often the Balinese would come to the beaches with far more livestock than the ships could carry. Lange took advantage of the situation. He bought the livestock that remained, especially the cattle, since beef was a popular food. He functioned as a beach butcher, where a man could have his cows butchered quickly. Dried beef, known as "ding-ding", was shipped to Dutch troops on Java.[13][14]

During those days, Lange's factorij had trading interests of a million guilders in trade with Java specifically. His success was primarily due to his ability to create personal ties, especially with the local Rajas. The Dutch, who were also trying to set up trade on Bali, were less successful, and in May 1844 they named Lange their agent on the island, with the right to fly the Dutch flag. Now Mads was not just working for himself, but also for the Dutch authorities who profited from his cooperation.

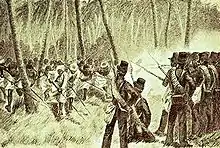

Peace broker

In the last half of the 1840s, the Dutch again tried to gain control over Bali and its Rajas. In July 1846 they sent a military force to the island, the First Dutch Expedition to Bali. Their goal was the northern city of Buleleng. After an ultimatum to surrender unconditionally was rejected, the Dutch landed on the island on 28 June and attacked the city. It was conquered and burned. The next day the Dutch troops marched for the residency of Singaraja, where this city was taken without much resistance ase most Balinese were moving inland to the fort of Djagaraga. During the attack, the Dutch received support from their fleet, whose commander would not allow the troops to move too far inland. Lange offered to go to the Rajas of Buleleng and Karangasem for negotiations. These were successful and on 9 July the peace accords came into effect. The Rajas would pay a small amount of damages, and the Dutch would maintain a small occupation force on the island until the matter could be settled.[11]

When the Rajas did not comply with all the agreements of the treaty of 1846, the Dutch sent a larger expedition to Bali in 1848, the Second Dutch Expedition to Bali. Lange was able to keep the states of Tabanan and Badung neutral, but the rest of the Balinese forces assembled at Djagaraga, the same place they had sought refuge in 1846. During the preparations for their campaign, the Dutch blockaded the coast of Bali, wreaking havoc on trade. Djagaraga lay deep inland, so the attack had to go through without the help of the fleet. At first all went well, but the Dutch were stopped when they met Gusti Djilantiek, who had dug in with 600 riflemen. When it became clear that the Dutch supply was badly organized, because there were not enough coolies to carry everything, the Dutch could no longer resist Balinese attacks from the villages and were forced to retreat.[15]

The Dutch defeat resonated through the Dutch East Indies and the government felt compelled to re-establish authority in order to prevent revolts in other parts of the archipelago. A new force twice the size of the previous one was sent in 1849, the Third Dutch Expedition to Bali. This time, the army brought along 200 coolies to carry supplies and the wounded. On 1 April 1849 the fleet reached Buleleng and on 4 April general-major Andreas Victor Michiels set up his headquarters in the abandoned palace of Singaraja. Emissaries of the Rajas of Buleleng and Karangasem were sent to the general, but he refused to talk to anyone but the Rajas themselves. He urged them to hurry up, or they would lose their territories. The meeting took place on 7 April. The Balinese arrived at the palace with a force of 12,000 men, after the Dutch had allowed them to take as many guards as the Rajas deemed necessary. Fighting did not occur, since the Rajas accepted all demands of the Dutch, including the immediate demolition of the fortifications at Djagaraga.[16]

The Dutch now decided to focus their attention on the south of Bali, and they attacked the small states of Karangasem and Klungkung. At the same time, they accepted an offer of 400 soldiers from the Prince of Lombok, who also coveted power over Karangasem. On 12 May 1849 preparations were complete, and the Dutch landed near the coastal town of Padang Cove, which they overtook. A week later, warriors from Lombok infiltrated in Karangasem, which rose in revolt against its Raja. The Raja, facing total defeat, killed all his wives and children and then committed suicide. The Raja of Buleleng, together with Gusti Djilantiek, fled into the mountains, with the warriors from Lombok in pursuit. The Dutch now focussed their attacks on Klungkung, where the most important and holiest Raja of Bali resided, the Dewa Agung. This Raja and his sister were the most fanatical opponents of Dutch influence on Bali, and it was of utmost importance to sideline them. Under command of major-general Michiels, the Dutch advanced and took control of an old, holy temple and the town of Kasumba. The next night, however, they were attacked by the Balinese, and Michiels was wounded in the thigh. He died after an unsuccessful amputation. The second in command, lieutenant-colonel Jan van Swieten, took over command and decided to retreat to the coast. There he waited for further instructions from Batavia. They were met by the warriors from Lombok, who informed them that the Raja and Gusti Djilantiek were no longer alive.[17]

Lange's trade suffered from the war, and when the Raja of Kassim launched an attack on neighbouring Mengwi, the people in Kotta feared a counter-attack. Mads convinced the Rajas to assemble a force of 16,000 men and join him on a journey to the Dewa Agung, to plead with him to conduct peace negotiations with the Dutch. Even though fortune favoured the Balinese after the death of Michiels and the retreat of the Dutch army, the Rajas decided to accept Lange's request. Lange had placed a man aboard his ship Venus and sent him ahead to inform the Dutch of his mediation. They were not convinced he would succeed, and when the monsoon season arrived, they decided that action needed to be taken lest the whole expedition fail. The army advanced on Kasumba and met almost no resistance. The Balinese had raised their defences around Klungkung. Early in the morning of 10 June, the Dutch left Kasumba for Klungkung. Along the way, they met Lange and a small group of riders. He informed them that his mediation had failed, but that the Rajas wished for peace. Mads also warned the Dutch not to advance any farther, for he could not guarantee that his 16,000 men would not join the Balinese defences. The Dutch were grateful for the information and retreated. They sent Lange back to the Rajas, together with a Dutch officer, to agree with the Rajas that the Balinese would send an embassy to the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies to recognize Dutch sovereignty over the island.[18]

A few days after the new commander of the military forces in the Dutch East Indies, Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, had arrived, Lange organised a meeting for all Dutch soldiers and 12,000 Balinese. The latter were extremely curious about this 'real' European prince. The Rajas and the prince assured each other of their peaceful intentions, after which the prince left for Batavia, taking most of the Dutch troops with him. Jan van Swieten was tasked with forging a final peace agreement with the Balinese princes. When the residences of the Rajas proved to be too small for the meetings, talks were held in Lange's factorij, which by that time was already a meeting place where quarrels between Balinese and foreigners were resolved. The meeting took place from 10 to 15 July. The Dewa Agung was ill and had sent his son Raja Geit Putera from Klungkung. The Rajas of Bandung, Tabanan, Gianyar and Mengwi were also present. Both parties saw the final arrangement as a victory. The Dutch left the island as sovereigns, and the Balinese would remain de facto independent for the rest of the 19th century.[19]

According to estimates, around 20,000 people attended the meetings, mostly Balinese. During the many days of negotiations, they all stayed in or around Lange's factorij. This must have been a huge drain on his resources. Raja Kassiman rewarded him for his efforts by granting him the honorary title of unggawa besar or high commissioner, one of the most senior titles on Bali. The Dutch for their part rewarded Lange with the Knight's Cross in the Order of the Netherlands Lion, awarded on 11 December 1849 by King William III. The newspaper of Langeland, the Danish island where Lange had been born, wrote in 1850 about the award:

His many great services and self-sacrificing toils in support of the Dutch, have finally been acknowledged by the Dutch government, both in the East Indies as well as in Europe, proven by the fact that last year he was named Knight in the Order of the Dutch Lion.[19][20]

Economic decline

After the war Bali suffered an economic decline, which also affected Lange and his business. The Dutch blockades during the military campaigns had practically stopped all trade. Also the majority of the male inhabitants had fought in the war instead of working the fields, leading to a standstill in the production of major export products. Lange was able to buy rice in Lombok and sell it to Raja Kassiman, but his expensive oil mill ground to a halt due to a shortage of coconuts.

At the same time as this drop in production, the number of ships in the waters around Bali dropped sharply. As skippers were not able to match their previous profits, their numbers declined. Sailing ship were out-competed by steamers, resulting in more traffic for large ports like Hong Kong and Singapore, and less for smaller places. Lange also suffered from illness, and a never-sent letter to the Raja of Tabanan shows he had plans to return to Rudkøbing.[21][22]

Relationship with Denmark

Lange had never forgotten his fatherland even though he had lived on Bali for most of his life. He sent several artefacts to the Royal Ethnographic Museum in Copenhagen, which was opened in 1849 by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen. After Lange's death, his sea chest was offered to the museum by a Swedish engineer who had acquired it on Bali. On 28 July 1854 the many gifts Lange had donated to the museum resulted in his being awarded the Danish Golden Medal of Merit by Frederik VII of Denmark. Papers in the Danish National Archives show the bureaucratic process surrounding this award:

Mads Lange was awarded the golden medal by Royal Order of 28 July 1854 resulting from a proposal by the Ministry for Culture. The initiative for this recognition of merit was taken by Christian Jürgensen Thomasen, who on 7th march sent a letter to the director of the Royal Gallery, nominating Mads Lange for donating valuable artifacts to the Ethnographic Museum. On the 11th may the director sent the proposal on to the Ministry for Culture, which lent its approval on 24 July, after which it was signed by Frederik VII on 28 July.[23]

Lange's contribution did not confine itself to the cultural sphere. He sent thousands of rijksdaalders to Denmark during the First Danish-German War of 1848–1851. He also collected money for the Danish organisation Aid for the Victims of War.

Death

Lange died on 13 May 1856, 48 years of age. His daughter Cecilia was only eight years old, but, like Lange's English physician, she suspected he had been poisoned during a visit to a Raja. There were also rumors he had been poisoned by the Dutch. Since no official inquiry has ever been made, it is impossible either to prove or to disprove any of those theories.[24]

In talks with writer Aage Krarup Nielsen, Cecilia accused Lange's nephew Peter Christian Lange of stealing everything Lange had of value and fleeing. According to Nielsen, she said, "He was a robber who left for home in Denmark with all that was left of my fathers riches, without leaving us two children a single penny."[25] Ludvig Verner Helms defended this nephew, based on a letter he had received in 1883 from one of Hans Nielsen Lange's sons, who wrote about Peter Christian Lange: "He sold everything that had belonged to my father, ships and buildings, nothing was left for me. The house in Banjuwangi was left to Cecilia, but because she had no documentary evidence that she was Lange's daughter, the government would not allow this."[lower-alpha 3][26]

Testament

Lange had drawn up a will in 1851. Krarup Nielsen received a copy of this will from his daughter Cecilia during one of her visits. It is highly likely that this copy still rests at the Royal Library in Copenhagen.

The reason why Lange had made a will at such a young age was the declining economic situation of his company. His planned trip to Denmark was also part of the decision. His brother had recently died in an accident, and making a will before undertaking a long and dangerous journey would have seemed like a good idea. A short while before writing the will Mads had lost his lover, the Balinese princess Nyai Kenyèr,[27] probably because of an outbreak of cholera.

According to the will, each of his children received a legacy of 10,000 guilders. Besides this, Cecilia would inherit all belongings and properties on Java, on the condition that her mother would be allowed to use these properties for the rest of her life. Cecilia's mother would inherit 3,000 pieces of gold, the interest on which would make her financially secure. Ida Bay, Lange's cousin, would inherit 4,000 gold pieces and 1,000 Spanish dollars, but she had to support Lange's mother, who would inherit all remaining assets. Lastly, two nephews, one in Rudkøbing and one on Bali, would each inherit 1,000 guilders. Around 1855, Mads changed his will: the first change was removing the name of his son William Peters due to his death in Singapore. The second change was the reduction of the legacy of his other son Andreas Emil to 5,000 guilders, and that Andreas would now inherit all his father's personal belongings and succeed him as head of the company. Cecilia's legacy was reduced by 25% and was frozen at a 9% interest rate. The funds would not be released until she married or reached adulthood.[28][29]

Grave

On one side of the obelisk a stone carries this inscription:[30]

SACRED

TO THE MEMORY

OF

MADS JOHANSEN LANGE

KNIGHT OF THE NEDERL: LEEUW

AND DANISH GOLD MEDAL

BORN IN THE ISLAND OF LANGELAND

DENMARK

18 SEPT. 1807

DEPARTED THIS LIFE AT BALI

13th MAY 1856

AFTER A RESIDENCE OF 18 YEARS

ON THIS ISLAND

Lange was buried near his factorij in a small grove of palm trees. Today the grave lies on the main road between Sanur and Kotta. An obelisk on a white base was erected in 1927 by the Dutch government, at the urging of the Danish consul at Surabaya, Johan Ernst Quintus Bosz.

Lange's grave

Lange's grave Bust at the gravesite

Bust at the gravesite Close-up of tombstone inscription

Close-up of tombstone inscription

The end of the business

Lange's brother Hans and his nephew Peter Christian tried to keep the factorij going after his death. The nephew even invested a large amount of his personal wealth. After Hans' death in 1860, Peter Christian was the only remaining Christian member of the family on Bali. After Raja Kassiman died in 1863, the factorij lost its protector. A short time later, Peter found himself in conflict with the Rajas. He subsequently sold the business to a Chinese merchant. He died in 1869 in Denmark at the age of 42.

Several times Cecilia and her half-brother tried in vain to get clear information about the value of their father's belongings on Bali. An investigation by the Dutch authorities in 1872 resulted in several lengthy exchanges of letters between the Raja and the Dutch. In the meantime, the once-flourishing company withered away. The empty factorij was abandoned and today no visible traces remain of its existence.

Descendants

Mads Lange never married. His whole life he hoped to marry his cousin Ida Bay, who was ten years younger than him. He sent her letters and gifts, but the feeling was clearly not mutual, and she did not even comment on the letter containing the marriage proposal from the east.

On Bali, Lange fathered three children with two women. One was a Balinese princess named Njai Kenjèr or Nyai Kenyèr.[31][lower-alpha 4] His second wife was a Chinese woman who Mads called Nonna Sangnio, which means "Miss" or "Mistress".

He had three children in total. With Nyai Kenyèr he had William Peter (1843) and Andreas Emil (1850), and with Nonna Sangnio he had Cecilia Catharina (1848). Both his sons went to school in Singapore. William Peter died here at twelve years of age. Andreas Emil was educated at the Raffles Institute, married a woman of European and Asian ancestry,[32] had several children, and was Private Secretary to the Rajah of Sarawak for at least eighteen years, during which time he had six sons and two daughters between 1881 and 1899.[33] Andreas's descendants live in Singapore and Australia.

Cecilia Catharina was sent to Singapore when she was seven years old to receive an education at a convent school. When Lange died the next year, she was adopted by an English family who took her on holidays to Europe and India. She received a thorough education, which proved to be of great use when she returned to Singapore in 1870. Here she met Abu Bakar, who was the ruler of Johor at the time. He fell in love with her and was so smitten he ignored all the customary stereotypes that in those days stood in the way of a marriage between a full-blooded Malay man and a Eurasian woman. They eventually married, and Cecilia took the name Zubaidah. She was not Abu Bakar's first wife, however, and when her husband became sultan in 1885 with the blessings of the British, it was his third wife Fatima who received the title of sultana. Cecilia was named "Inche Besar Zubaidah", a title bestowed upon wives of the sultan who were not sultana. But in contrast to his other wives, it was Cecilia who bore him a son and continued the dynasty. Her son Ibrahim is a descendant of Lange, and his family sits on the throne of Johor to this very day.[34]

Notes

Former New Zealand prime minister David Lange, who is known to be of Danish ancestry, is descended from a different branch of the family, according to himself.[35]

- Some sources name him as Lorentz, with a 'z' instead of an 's'.

- In reality the Raja escaped alive.

- It was believed that Cecilia would inherit the house on Java, but the government denied this.

- The spelling is uncertain. Her name appears in one letter only, which she wrote to Mads Lange from Tabanan.

References

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 20.

- Mads Lange, 2007, retrieved 11 September 2023

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 36.

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 60.

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 61.

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 62.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 41.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 56.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 48.

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 37.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 69.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 128.

- Andresen 1992, p. 26.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 85.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 101.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 109.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 113.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 115.

- Andresen 1992, p. 32.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 117.

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 64.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 127.

- Andresen 1992, p. 33.

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 65.

- Andresen 1992, p. 54.

- Andresen 1992, p. 55.

- Andreas Emil Lange, Penjawat Awam Brooke Di Sarawak Dan Kerabat Diraja Johor - The Patriots, 2019, retrieved 11 September 2023

- Andresen 1992, p. 61.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 140.

- Rasmussen 2007, p. 67.

- Andreas Emil Lange, Penjawat Awam Brooke Di Sarawak Dan Kerabat Diraja Johor - The Patriots, 2019, retrieved 11 September 2023

- Andreas Emil Lange, Penjawat Awam Brooke Di Sarawak Dan Kerabat Diraja Johor - The Patriots, 2019, retrieved 11 September 2023

- "The old Mads Lange Familytree - Rudkøbing Byhistoriske Arkiv". byarkivet.langelandkommune.dk (in Danish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Nielsen 1949, p. 134.

- Andresen 1992, p. 43.

Sources

- Andresen, Paul (1992). Mads Lange fra Bali og hans efterslægt sultanerne af Johor (in Danish). Odense: Odense Universitetsforlag. ISBN 87-7492-851-1.

- Gravensten, Eva (2007). Mads Lange, roi de Bali — Un pionnier danois et son temps (in French). Paris: Esprist Ouvert. ISBN 978-2-88329-077-8.

- Helms, Ludvig Verner (2008) [1882]. Pioneering in the Far East: And Journeys to California in 1849 and to the White Sea in 1878. BiblioLife. ISBN 978-0-559-53434-8.

- Nielsen, Aage Krarup (1949) [1925]. Mads Lange til Bali. En dansk Ostindiefarers Liv og Eventyr (in Danish) (5 ed.). Kopenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel og Nordisk Forlag.

- Pringle, Robert (2004). Bali: Indonesia's Hindu Realm; A short history of. Short History of Asia Series. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-863-3.

- Rasmussen, Doris (2007). En Vild Krabat — Mads Johansen Lange (in Danish). Forlaget Mea. ISBN 978-87-991982-0-7.