Magdeburg Cathedral

Magdeburg Cathedral (German: Magdeburger Dom), officially called the Cathedral of Saints Maurice and Catherine (German: Dom zu Magdeburg St. Mauritius und Katharina), is a Protestant cathedral in Germany and the oldest Gothic cathedral in the country. It is the proto-cathedral of the former Prince-Archbishopric of Magdeburg. Today it is the principal church of the Evangelical Church in Central Germany. The south steeple is 99.25 m (325 ft 7 in) tall, the north tower 100.98 m (331 ft 4 in), making it one of the tallest cathedrals in eastern Germany. The cathedral is likewise the landmark of Magdeburg, the capital city of the Bundesland of Saxony-Anhalt, and is also home to the grave of Emperor Otto I the Great and his first wife Edith.

| Magdeburg Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of Saints Maurice and Catherine | |

Magdeburger Dom | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| 52°07′29″N 11°38′04″E | |

| Location | Magdeburg |

| Country | Germany |

| Denomination | Lutheran |

| Previous denomination | Catholic |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | cathedral (formerly) principal church |

| Architectural type | basilica |

| Style | Gothic |

| Completed | 1520 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 120 m (393 ft 8 in) |

| Width | 42.6 m (139 ft 9 in) |

| Height | 32 m (105 ft 0 in) |

| Number of spires | 2 |

| Spire height | 100.98 m (331 ft 4 in) (North tower) 99.25 m (325 ft 7 in) (South tower) |

| Bells | 4 |

| Tenor bell weight | 8800kg |

The first church built in 937 at the location of the current cathedral was an abbey called St. Maurice, dedicated to Saint Maurice. The current cathedral was constructed over the period of 300 years starting from 1209, and the completion of the steeples took place only in 1520. Despite being repeatedly looted, Magdeburg Cathedral is rich in art, ranging from antiques to modern art.

History

Previous building

.jpg.webp)

The first church was founded September 21, 937 at the location of the current cathedral was an abbey called St. Maurice (St. Moritz), dedicated to Saint Maurice and financed by Emperor Otto I, the Great. Otto wanted to demonstrate his political power after the successful Battle of Lechfeld in 955, and ordered the construction even before his coronation as Emperor on February 2, 962. Furthermore, to support his claim as successor of the Emperor of the Weströmisches Reich, he obtained a large number of antiques – for example, pillars to be used for the construction of the church. Many of those antiques were subsequently used for the second church in 1209. The church had most likely one nave with four aisles, a width of 41 meters and a length of 80 meters. The height is estimated as up to 60 meters.

The wife of Otto, Queen Eadgyth (grand-daughter of Alfred the Great), was buried in the church after her death in 946; isotopic analysis of her bones confirms her early life in Wessex. The church was expanded in 955. Hence, the church became a cathedral. In 968, Emperor Otto I selected Magdeburg as the seat of an archdiocese with Adalbert von Trier as archbishop, even though the city was not centrally located but at the eastern border of his kingdom. He did this because he planned to expand his kingdom, and also Christianity, to the east into what is nowadays Poland. This plan, however, failed. Emperor Otto I died soon thereafter in 973 in Memleben and was also buried in the cathedral next to his wife.

The entire cathedral St. Maurice was destroyed on Good Friday in 1207 by a city fire. All but the southern wing of the cloister burned down. Archbishop Albrecht II von Kefernburg decided to pull down the remaining walls and construct a completely new cathedral, against some opposition of the people in Magdeburg. Only the south wall of the cloister is still standing. The exact location of the old church remained unknown for a long time, but the foundations were rediscovered in May 2003, revealing a building 80 m long and 41 m wide. The old crypt has been excavated and can be visited by the public.

The place in the north of the cathedral (sometimes called "new marketplace", Neuer Markt, now: Cathedral square = in german language: Domplatz) was occupied by an imperial palace (Kaiserpfalz), which was destroyed in the fire of Good Friday 1207. In the southeast corner of the Domplatz standed a second large church, the "North Church", burned down 1207 and was not rebuilt after the fire.[1] The stones of the ruin served for building the cathedral. The presumptive remains of the palace were excavated in the 1960s.

Construction of the current building

The highly educated Prince-Archbishop Albert I of Käfernburg, having traveled in Italy and France, decided to construct the new cathedral modelled upon the Gothic architecture that had intrigued him in France. The French style was completely unknown in Germany, and the hired craftsmen only gradually mastered it.

The construction of the choir started in 1209, only two years after the fire that destroyed the previous church, but this choir is still in a very Romanesque style, initially still using romanesque groin vaults, combined with a gothic center stone, which however is not needed for Romanesque groin vaults.

The Gothic influence increased especially between 1235 and 1260 under Archbishop Wilbrand. As the construction was supervised by different people in the span of 300 years, many changes were made to the original plan, and the cathedral size expanded greatly. The people of Magdeburg were not always happy with this, since they had to pay for the construction. In some cases already constructed walls and pillars were torn down to suit the wishes of the current supervisor.

Construction stopped after 1274. In 1325, Archbishop Burchard III. von Schraplau was killed by the people of Magdeburg because of extreme taxes. Folklore says that especially the beer tax increase caused much anger. Afterwards Magdeburg was under a ban, and only after the donation of five atonement altars did the construction of the cathedral continue under Archbishop Otto von Hessen. Otto was also able to complete the interior construction, and formally opened the dome in 1363 in a week-long festival. At this time, the cathedral was dedicated not only to St Maurice as before, but also to Saint Catherine.

In 1360, the construction stopped again after the uncompleted parts have been covered provisionally. Only in 1477 did the construction start again under Archbishop Ernst von Sachsen, including the two towers. The towers were constructed by master builder Bastian Binder, the only master builder of the cathedral known by name. The construction of the cathedral was completed in 1520 with the placement of the ornamental cross on the north tower.

Luther, the Swedes, and Napoleon

On October 31, 1517 Martin Luther published the 95 Theses in Wittenberg, Germany, an event considered to mark the start of the Protestant Reformation. Luther preached in Magdeburg in 1524, and some smaller churches in the city to adopt Protestantism soon thereafter. The unpopularity of Archbishop Albrecht von Brandenburg also furthered the Reformation, and after his death in 1545 in Mainz there was no successor. Magdeburg became a leading site of the Reformation, and was outlawed by the emperor. The Catholic Church stored the cathedral treasure in Aschaffenburg for safekeeping, but it would later be lost to the Swedes in the Thirty Years' War. The priests of the cathedral also converted to Protestantism, and on the first Advent Sunday in 1567, the first Protestant worship service was held in the cathedral.

The largest bell, the "Maxima" with 10 tons in the south tower, falls down and was destroyed in the 1540th years.

Heinrich Compenius built 1604/05 his famous main organ with the "Golden Chick".

In 1631, during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) Magdeburg was raided, and only a small group of 4000 citizens survived the murdering, raping, and looting (known as the sack of Magdeburg) by seeking refuge in the cathedral. The head priest, Reinhard Bakes, begged on his knees for the lives of his people before the conqueror Johan t'Serclaes, Count of Tilly. The cathedral survived the fires in the city, and was dedicated again to the Catholic religion. However, as Tilly's catholic forces left Magdeburg, the cathedral was completely looted, and its colorful windows were shot out. Twenty thousand people of Magdeburg died during the war, and at the end of the war Magdeburg had a population of only 400. Magdeburg became part of Brandenburg, and was transformed into a large fortress. In 1806, Magdeburg was given to Napoleon, and the cathedral was used for storage, and also as a horse barn and sheep pen. The occupation ended in 1814, and the cathedral changed in the ownership of prussian state. Between 1826 and 1834 Frederick William III of Prussia financed the much-needed repairs and reconstruction of the cathedral under the leaderness from Karl Friedrich Schinkel. A new main organ IV/81 with mechanical key and stop action was built 1856 to 1861 by Adolf Reubke, 1865 a new division with 6 stops was added. The cathedral organist from 1847 to 1885 was August Gottfried Ritter. He designed the stoplist for the Reubke-Organ.[2] The glass windows were all replaced in 1900.

20th and 21st centuries

In 1901 a steam heating was installed. It needed one railway car with coal to made a temperature from 57,2 °F = 14 °C in winter. Ernst Röver build a new main organ with pneumatic key and stop action, 3 manuals and 100 stops in 1906.

The frequent Allied bombings of World War II completely destroyed the windows of the cathedral. During the heaviest bomb attacks on January 16, 1945, some vaults was destroyed. Im February or March 1945 one firebomb from a deep flying attack hit the cathedral on the west facade between the towers, destroying the facade and the Röver-organ. Fortunately, the fire brigades were able to extinguish the flames on the roof structures in time, so damage to the cathedral was only moderate. Also the steam heating was destroyed in WW II and to now not rebuilt. The cathedral was opened again in 1955, and a new organ with mechanical action and 37 stops from Alexander Schuke Orgelbau was installed over the "paradies door" in 1969.

With the end of World War II and the establishment of the communist-led German Democratic Republic in 1949, Magdeburg fell under Soviet control and the ownership of the cathedral to the GDR. Communist leaders tried to suppress religion as a potential threat to communist doctrine, thus being active in church was a social disadvantage. The eradication of religion could not be accomplished, however, and weekly peace prayers were held in the cathedral beginning in 1983 in front of the Magdeburger Ehrenmal, a sculpture by Ernst Barlach. This led to the famous Monday demonstrations of 1989 (similar to those in Leipzig), which played a significant role in the German reunification process.

The cathedral is currently undergoing a reconstruction phase that began in 1983 under the East German Government. In 1990, a number of solar cells were installed on the roof, marking the first solar cell installation on a church in East Germany. The solar cells provide energy for use in the church, with excess energy being added to the regional power network. The maximum output was 418 watts. In 2004, a funding drive started in 1997 for a new main organ was completed, collecting €2.2 million. The new main organ was built by the firm of Alexander Schuke Orgelbau (Werder an der Havel) near Potsdam and was completed in May 2008 and dedicated on Trinity Sunday, May 18, 2008. Specs: ~36 tonnes, 4 manuals, 93 stops and 6193 pipes.[3]

Barry Jordan of Port Elizabeth, South Africa was appointed as Organist and Choral director of the cathedral in August 1994.[4]

The Magdeburger Ehrenmal (Monument) in the cathedral is once again the starting point of many Monday demonstrations, but this time the demonstrations are aimed against social reforms reducing government welfare. However, these demonstrations occur on a much smaller scale, so comparisons to the Monday demonstrations of 1989 are made mainly for publicity reasons.

In the next time the little Schuke-organ will be restored: New case and new facade pipes, new trumpets in the Great und the Pedal, and a new Vox Humana.

Bells

Many of the historic bells were used in the 16th and 17th centuries for the production of weapons. Today there are four historic bells left in the cathedral:

1) the Susanne = Osanna, 8800 kg, tone e0, manufactured in 1702 by Johann Jacobi in Berlin,

2) the Apostolica, 4980 kg, tone b0, manufactured in 1690 by Jakob Wenzel in Magdeburg, it also hits the full hours

3) the Dominica, 2362 kg, tone h0, manufactured in 1575 by Eckart Kucher in Magdeburg,

4) the Orate, 200 kg, tone e2, manufacturing date and manufacturer unknown (13th century?)

The Schelle, 1500 kg, tone f1, manufactured in 1396, is only for the clock and hits the quarters of a hour.

The two largest bells and the Schelle are in the North tower, the Orate since 1994 in the spire. The "Dominica" was out of order since ≈2004, but it has been repaired in summer 2019, and now is awaiting installation together with the new "Amemus" in the North tower in the following years.

In the next years eight new bells from 440 kg to 14000 kg will be installed in both towers. The first new bells, the "Amemus" with 6525 kg (tone g0) for the North tower and the "Benedicamus" with 1300 kg (tone e1) for the South tower were manufactured in September and October 2022 by the Bell-manufacturer Bachert in Neunkirchen. The next five little bells for the south tower with the tones d1, f sharp1, g1, a1 and h1, made by Bachert, followed in 2023.[5] The "Credamus" with 14 metric tons and the tone d0 will be installed at the former place of the "Maxima" (destroyed in 1540) in the South tower and will be the second heaviest ringing bell in Germany (after the Petersglocke in Cologne cathedral).[6]

Architecture

The current cathedral was constructed over a period of 300 years starting from 1209, and the completion of the steeples took place only in 1520. As there were no previous examples of gothic architecture in Germany, and German craftsmen were still very unfamiliar with the style at the start of the construction. Hence they learned by doing, and their progress can be seen in small architectural changes over the construction periods, which started with the Sanctuary in the east side of the church near the river Elbe and ended with the top of the towers. This sanctuary shows a strong Romanesque architecture influence. Unlike most other Gothic cathedrals, Magdeburg Cathedral does not have flying buttresses supporting the walls.

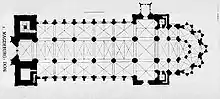

The building has an inside length of 120 metres, and a height to the ceiling of 32 metres. The towers rise to 99.25 and 100.98 metres, and are among the highest church towers in eastern Germany. The layout of the cathedral consists of one nave and two aisles, with one transept crossing the nave and aisles. Each side of the transept has an entrance, the south entrance leading into the cloister. The ceiling in the nave is higher than in the aisles, allowing for clerestory windows to give light to the nave. There is a separate narthex (entrance area) in the west. The presbytery in the east is separated from the nave by a stone wall, serving the same function as a rood screen. The sanctuary and the apse follow the presbytery. The apse is also surrounded by an ambulatory. (See Cathedral diagram for details on cathedral layouts.)

A secondary building around a large non-rectangular cloister is connected to the south side of the cathedral. The cloister, whose south wall survived the fire of 1207 and is still from the original church, was parallel to the original church. Yet, the current church was constructed at a different angle, and hence the cloister is at an odd angle with the church.

The ground around the Elbe river in Magdeburg is soft, and it is difficult to construct tall buildings, except for one large rock. Hence the cathedral was constructed on top of this rock, called the Domfelsen in German, which means Cathedral Rock. At low water levels, this rock is visible in the Elbe. As in old times low water meant a small harvest, this rock is also called Hungerfelsen, meaning starvation rock. In any case, the rock was not big enough for the cathedral, and on the west end only the north tower could be placed on a solid rock foundation, whereas the south tower stands on soft ground. To reduce weight the south tower is therefore only an empty shell with no interior or stairs, and the three big bells, "Susanne" (e), "Apostolica" (b♭) and "Dominica" (b), are in the north tower with a solid rock foundation. However, the south tower is slightly higher than the north tower, which is optically corrected by adding an ornamental cross on the north tower.

Art

Despite having lost much to plunderers, Magdeburg Cathedral is rich in art, ranging from antiquities to modern art. Highlights include:

- Marble porphyry and granite columns removed from buildings in Ravenna for use in the apse of the Ottonian basilica;

- The late-antique, porphyry baptismal font.

- The tomb of Otto I, the first Ottonian Holy Roman Emperor (962 - 973). When the tomb was opened in 1844, a skeleton and remains of clothes were found, but no grave goods, which were presumably stolen during the Thirty-Years War. The Latin inscription on the bronze plaque is modern.

- The (incomplete) sculpture of Saint Maurice, created around 1250, is the first realistic depiction of an ethnic African in central European art. It shows the same high degree of naturalism as the founder's effigies of Naumburg Cathedral. The same sculptor carved the image of Saint Catherine.

- The sculpture known as The Royal Couple (Herrscherpaar), located in the sixteen-sided chapel, also dates from c. 1250) may represent Otto I and his consort, Edith.

- The sculptures of the five wise and the five foolish virgins (see The ten virgins from the List of Bible stories), also around 1250. This is the most remarkable piece of art in the cathedral. The five wise virgins are prepared and bring oil to a wedding, whereas the five foolish virgins are unprepared and bring no oil. Hence they have to go find oil and subsequently arrive late and cannot join the wedding anymore. The unknown artist masterfully expresses the emotions in the faces and the body languages of the girls, showing a much more realistic expression than what was common in art around that time. All figures are different, and have ethnic Slavic features. The sculptures are outside of the north entrance to the transept.

- The seats in the choir from 1363 are masterfully carved and show the life of Jesus. The unknown master also created the seats in the choir in Bremen's Cathedral.

- The Magdeburger Ehrenmal by Ernst Barlach was ordered as a heroic war memorial, but due to his voluntary participation during World War I Barlach was against the war and showed the pain and suffering of the war instead. This created a great controversy, and the work was almost destroyed. The spot in front of this sculpture was also the starting point of the Monday demonstrations.

- The Lebensbaumkruzifix (literally: Tree of life cross) is a painted bronze sculpture from 1986 and expanded in 1988 that shows Jesus nailed to a tree instead of a cross. Jesus is attached to the tree only with his hands and feet, and is otherwise hanging freely. The sculpture was designed not only to be viewed from the front but from all sides. The tree is barren except for a small leaf of hope/life where the blood of Jesus drips on the tree. The artist, Prof. Jürgen Weber, wanted the sculpture to be the centerpiece near the altar, but the sculpture was placed on the south side of the transept against his wishes.

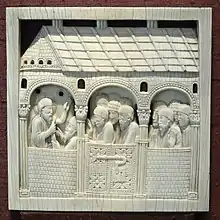

- The Magdeburg Ivories, 17 carved panels thought to be created for an unidentified object in Magdeburg Cathedral around the time of its dedication and now dispersed in museums across the world, a prime example of Ottonian art.

Saint Maurice

It was not until the Middle Ages that the portrayal of blackness arose in art,[7] evident in the sculpture of Saint Maurice in Magdeburg Cathedral. However, during this time, much of the portrayal of blackness in art was to emphasize social and racial hierarchy, so, by portraying blackness in sculpture, it was easier for viewers to understand that the use of different skin colors was to demonstrate "the other."[8] The attention to black facial structure to portray foreignness can be traced back to Hohenstaufen iconography and the Crusades, as there was a rising interest in black social standing during the period.[9] This led to the emergence of black portrayals in art, particularly under Frederick II, who had black Muslims brought to Lucera, Apulia, to become his personal servants. Thus they became a large part of the art he commissioned.[10] During Fredericks's reign, due to his interest in the Hohenstaufen tradition, black people were depicted as servants, specifically intelligent guardians of the royal treasury, or in high court positions. Yet, rather than defining them through race, there was greater attention to detail in facial structure, which was used to indicate their foreignness.[11] Looking at Saint Maurice, it is clear that he embodies the traits of the time, and the shift towards naturalism in sculpture during the Gothic period, as there is a focus on the portrayal of his distinctly black features.[12] The statue of Saint Maurice changed the idea of black Africans in art from a violent and savage-like stereotype to that of a saint and martyr.[12] The portrayal of Saint Maurice in a position of power is evident through his clothing, as he is dressed as a mighty knight, making it clear that he is not a servant. This sculpture not only represents blackness, but the importance of African ancestry as well, as this sculpture was one of the earliest representations of a black African in European art history.[12] This statue thus became a model in the representation of blackness in medieval European sculpture.

References

- Magdeburg, Touristische Informationen über. "Ausgrabungen auf dem Domplatz". Touristische Informationen über Magdeburg (in German). Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- "Organs". www.domorgel-magdeburg.de. Retrieved 2022-11-13.

- "Magdeburger Dommusik website". Archived from the original on 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- "Organs". www.domorgel-magdeburg.de. Retrieved 2022-11-13.

- redakteur@domglocken (2023-08-28). "Letzte der "kleinen" Glocken die SPEREMUS begrüßt". Domglocken Magdeburg e.V. (in German). Retrieved 2023-09-24.

- "Sanierung, Klangsimulation". Domglocken Magdeburg e.V. (in German). Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- Patton, Pamela A. (2019). "Blackness, Whiteness, and the Idea of Race in Medieval European Art". In Albin, Andrew; Erler, Mary C; O'Donnell, Thomas; Paul, Nicholas L; Rowev, Nina (eds.). Whose Middle Ages?: Teachable Moments for an Ill-used Past. Fordham University Press. p. 154.

- Patton, Pamela A (2019). "Blackness, Whiteness, and the Idea of Race in Medieval European Art". In Albin, Andrew; Erler, Mary C; O'Donnell, Thomas; Paul, Nicholas L; Rowev, Nina (eds.). Whose Middle Ages?: Teachable Moments for an Ill-used Past. Fordham University Press. pp. 155–158.

- Kaplan, Paul H. D. (1987). "Black Africans in Hohenstaufen Iconography". Gesta. 26 (1): 29. doi:10.2307/767077. JSTOR 767077. S2CID 190825271.

- Kaplan, Paul H. D. (1987). "Black Africans in Hohenstaufen Iconography". Gesta. 26 (1): 32.

- Kaplan, Paul H.D. (1987). "Black Africans in Hohenstaufen Iconography". Gesta. 26 (1): 31–32.

- Geraldine, Heng (2014). "An African Saint in Medieval Europe: The Black Saint Maurice and the Enigma of Racial Sanctity". In Bassett, Molly H.; Lloyd, Vincent W. (eds.). Sainthood and Race: Marked Flesh, Holy Flesh. Routledge. pp. 18–21.

Sources

- Nicola Coldstream (2002) "Medieval Architecture", Oxford History of Art, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-284276-5.

- "Der Dom zu Magdeburg", DKV Kunstführer Nr. 415/2, Munich.

- Buchholz, Ingelore (2001): Magdeburg: Der Stadtführer, Verlag Janos Stekovics, ISBN 3-932863-84-4.

- Sussman, Michael (1997): Der Dom zu Magdeburg, Passau.

- Ullmann, Ernst (1989): Der Magdeburger Dom: ottonische Gründung und staufischer Neubau, Leipzig