Magnolia warbler

The magnolia warbler (Setophaga magnolia) is a member of the wood warbler family Parulidae.

| Magnolia warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| An adult male in Quebec | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Setophaga |

| Species: | S. magnolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Setophaga magnolia (Wilson, 1811) | |

| |

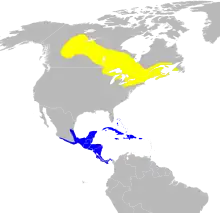

| Range of the S. magnolia Breeding range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dendroica magnolia | |

Etymology

The genus name Setophaga is from Ancient Greek ses, "moth", and phagos, "eating", and the specific magnolia refers to the type locality. American ornithologist Alexander Wilson found this species in magnolias near Fort Adams, Mississippi.[2]

Description

This species is a moderately small New World warbler. It measures 11 to 13 cm (4.3 to 5.1 in) in length and spans 16 to 20 cm (6.3 to 7.9 in) across the wings. Body mass in adult birds can range from 6.6 to 12.6 g (0.23 to 0.44 oz), though weights have reportedly ranged up to 15 g (0.53 oz) prior to migration. Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 5.4 to 6.4 cm (2.1 to 2.5 in), the tail is 4.6 to 5.2 cm (1.8 to 2.0 in), the bill is 0.8 to 1 cm (0.31 to 0.39 in) and the tarsus is 1.7 to 1.85 cm (0.67 to 0.73 in).[3][4] The magnolia warbler can be distinguished by its coloration. The breeding males often have white, gray, and black backs with yellow on the sides; yellow and black-striped stomachs; white, gray, and black foreheads and beaks; distinct black tails with white stripes on the underside; and defined white patches on their wings, called wing bars.[5] Breeding females usually have the same type of coloration as the males, except that their colors are much duller. Immature warblers also resemble the same dull coloration of the females.[6] The yellow and black-striped stomachs help one to distinguish the males from other similar birds, like the prairie warbler and Kirtland's warbler (which, however, have a breeding range to the south and east of the magnolia warbler's).[5]

Distribution

The magnolia warbler is found in the northern parts of some Midwestern states and the very northeastern parts of the US, with states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin comprising its southernmost boundaries. However, it is mostly found across the northern parts of Canada, such as in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. During the winter, the warbler migrates through the eastern half of the United States to southern Mexico and Central America.[7] The warbler breeds in dense forests,[6] where it will most likely be found among the branches of young, densely packed, coniferous trees.[5] The magnolia warbler migrates to the warmer south in the winter, wintering in southeastern Mexico, Panama, and parts of the Caribbean. In migration it passes through the eastern part of the United States as far west as Oklahoma and Kansas.[8] During migration season, the magnolia warbler can be found in various types of woodlands.

Life cycle

The magnolia warbler undergoes multiple molts during its lifetime. The first molts begin while the young offspring are still living in the nest, while the rest take place on or near their breeding grounds.[5] The warblers molt, breed, care for their offspring, and then migrate. Chicks hatch after a two-week incubation period, and can fledge from the nest after close to another two weeks when their feathers are more developed. After about a month, the chicks can leave the nest to begin living (and later breeding) on their own since they are solitary birds. Magnolia warblers typically live up to seven years.[9]

Behavior

Diet and feeding

This warbler usually eats any type of arthropod, but their main delicacies are caterpillars.[10] The warbler also feeds on different types of beetles, butterflies, spiders, and fruit during their breeding season, while they increase their intake of both fruit and nectar during the winter.[5] These birds also tend to eat parts of the branches of mid-height coniferous trees, such as spruce firs,[10] in their usual breeding habitat.

Songs

Researchers have observed two different types of songs in male magnolia warblers. Their songs have been referred to as the First Category song and the Second Category song.[11] Females have not been observed to have a distinct song yet as the males have; while they do sing, they don't have separate songs for different situations. In general, the male warblers use their songs during the spring migration season and during the breeding season: one is used for courtship and the other is used to mark their territory each day.[11] Both males and females have call notes that they use for various alerts: the females have short call notes to signal when a human observer is watching them, and the males have short call notes to signal when any sort of threatening predators are close to their offspring.

Reproduction

Male magnolia warblers go to their breeding grounds about two weeks before the females arrive. After the females come to the breeding grounds, both the males and females cooperate to build the nest for a week. Because of the difficulty of locating their nests among the forest's dense undergrowth, it is hard to know whether the warblers re-use their original nests each breeding season, or whether they abandon them for new ones. The nests are built in their tree of choice – different types of fir trees, such as Abies balsamea (balsam fir) and Picea glauca (spruce fir).[6] The nest is made up of grass, twigs, and horsehair fungus, and they are relatively small, shallow, circular-shaped nests, barely exceeding 10 cm on all sides.[5] The nests are usually found close to the ground, commonly in the lowest three meters of the firs.

Female magnolia warblers usually lay three to five eggs during each breeding season. The female will not incubate her eggs until all of them are laid. The female sits on the eggs for about two weeks before the eggs hatch. The female is also the one that warms the newborn chicks by brooding, or sitting, on the nest; she is also the one who feeds the newborn chicks most frequently, though the males also engage in feeding the offspring at times.[12] Because the males are technically as equally responsible for feeding the newborns as the females are, this means that the males are monogamous because they expend a large amount of energy looking for food for their young. In order to keep the nest clean, females eat the fecal sacs of their newborns; as the chicks grow older, both parents simply remove the sacs from the nest. The baby warblers are ready to fly out of the nest by the time they are ten days old.

Conservation

The magnolia warbler is assessed on the IUCN Red List as least concern for conservation because it is fairly widespread and common within its habitat and not at risk of extinction. Research has shown that a good percentage of warblers die from flying into television towers in their migratory path. Also, parts of their habitat have been degraded as coniferous forests are cleared which causes the number of warblers living in a habitat to decrease, but they certainly are not greatly affected by the deforestation. While the deforestation does decrease the warbler population in the specific area that it occurs in, the species is not significantly impacted overall due to the general abundance of the species throughout the region.[1][13]

In art

John James Audubon illustrated the magnolia warbler in The Birds of America, Second Edition (published, London 1827–38) as Plate 123 under the title, "Black & Yellow Warbler – Sylvia maculosa" where a pair of birds (male and female) are shown searching flowering raspberry for insects. The image was engraved and colored by Robert Havell's London workshops. The original watercolor by Audubon was purchased by the New York History Society.

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Setophaga magnolia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22721667A94721402. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22721667A94721402.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. pp. 238, 355. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- "Magnolia Warbler, Life History, All About Birds – Cornell Lab of Ornithology". Allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- Curson, Jon; Quinn, David; Beadle, David (1994). New World Warblers. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-3932-6.

- Dunn, E.; Hall, G. A. 2010. (1994). "Magnolia Warbler (Dendroica magnolia)". In Poole, A. (ed.). The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bna.136.

- 2009. Magnolia Warbler (Dendroica magnolia). Audubon Guides (Allied with National Audubon Society).

- Hitch, A. T.; Leberg, P. L. (2007). "Breeding Distributions of North American Bird Species Moving North as a Result of Climate Change". Conservation Biology. 21 (2): 534–539. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00609.x. PMID 17391203.

- Boone, A. T.; Rodewald, P. G.; Degroote, L. W. (2010). "Neotropical Winter Habitat of the Magnolia Warbler: Effects on Molt, Energetic Condition, Migration Timing, and Hematozoan Infection During Spring Migration". The Condor. 112: 115–122. doi:10.1525/cond.2010.090098. S2CID 86231672.

- National Geographic field guide to the birds of North America (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. 2002.

- Morse, D. H. (1976). "Variables Affecting the Density and Territory Size of Breeding Spruce-Woods Warblers". Ecology. 57 (2): 290–301. doi:10.2307/1934817. JSTOR 1934817.

- Morse, D. H. (1989). "Song Patterns of Warblers at Dawn and Dusk" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. Wilson Ornithological Society. 101 (1): 26–35.

- Allen, J.; Islam, K. (2004). "Gender Differences in Parental Feeding Effort of Cerulean Warblers at Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge, Indiana". Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science. 113 (2): 162–165. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2014.

- Germaine, S. S.; Vessey, S. H.; Capen, D. E. (1997). "Effects of Small Forest Openings on the Breeding Bird Community in a Vermont Hardwood Forest" (PDF). The Condor. 99 (3): 708–718. doi:10.2307/1370482. JSTOR 1370482.

External links

- "Magnolia warbler media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Magnolia warbler photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Magnolia warbler species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Magnolia warbler - Dendroica magnolia - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter