Royal Palace Complex of Kandy

The Royal Palace of Kandy, situated in the city of Kandy, Sri Lanka, is a captivating historical complex that served as the official residence for the monarchs of the Kingdom of Kandy until the advent of British colonial rule in 1815. Noteworthy for its adherence to traditional Kandyan architectural styles, the palace complex boasts intricate woodwork, finely crafted stone carvings, and ornate wall murals. This complex encompasses a range of structures, including the Audience Hall, the Queen's Palace, the King's Palace, and the renowned Temple of the Tooth Relic. Within this royal domain lies the Temple of the Tooth, a profoundly venerated Buddhist temple with global significance. Both the palace complex and the Temple of the Tooth have earned the prestigious recognition of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

| Royal Palace of Kandy | |

|---|---|

කන්ද උඩරට මාලිගාව | |

Royal Palace Complex of Kandy | |

| General information | |

| Type | Royal palace (former) |

| Architectural style | Kandyan |

| Town or city | Kandy District, Kandy |

| Country | Sri Lanka |

| Current tenants | Temple of the Tooth |

| Website | |

| http://www.sridaladamaligawa.lk | |

History

The annals of the Royal Palace of Kandy trace a narrative that unfolds across several centuries, entwined with the reigns of diverse monarchs and leaders. In the 14th century, the inaugural palace emerged under the directive of Vickramabahu III. Centuries later, during the late 16th century, Vimaladharmasuriya I took up residence within these walls and instigated a series of enhancements to the existing palace complex. The early 17th century ushered in a tumultuous period marked by the incursion of Portuguese invaders, resulting in the destruction of the palace during the tenure of Senarat. Notwithstanding these adversities, resilience prevailed, and the palace was meticulously resurrected in 1634 by Rajasinha II.

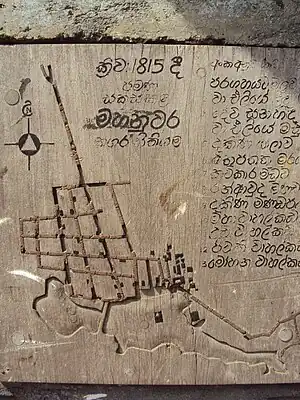

Map of Kandy during Wimaladharamasooriya I era with Royal Palace and surroundings, drawn by Portuguese envoys

Map of Kandy during Wimaladharamasooriya I era with Royal Palace and surroundings, drawn by Portuguese envoys

Location and architecture

Throughout its history, the Royal Palace of Kandy has undergone shifts in its geographical placement. The inaugural palace initially graced a location across from its present site.[1] The era of King Vimaladharmasuriya I introduced a transformation influenced significantly by Portuguese architectural aesthetics. Foreign accounts from the Portuguese era intricately delineate the palace complex, revealing a stark contrast to the architecture extant in the present day.

Invasions and destruction

The Royal Palace of Kandy grappled with a series of invasions that resulted in its repeated destruction. Numerous edifices within its confines fell victim to these adversities, leaving only a handful of structures that endure to this day. Notwithstanding the challenges, the monarchs of the Kandyan Kingdom displayed their resilience by orchestrating the palace's reconstruction across different epochs, imprinting their individualistic architectural signatures onto the complex.

Kandy in 1736: A Historic Map Featuring the Royal Residence, by Johann Wolfgang Heydt

Kandy in 1736: A Historic Map Featuring the Royal Residence, by Johann Wolfgang Heydt

Evolution

.jpg.webp)

From the year 1760 onward, a pivotal alteration unfolded as the Royal Palace of Kandy transitioned its location from the western precincts to the eastern fringes. Under the reign of King Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, the palace complex underwent profound metamorphoses. Within its expansive domain resided an array of structures, notably the Queens' Palace, the Hall of Audience, and the venerated Temple of the Tooth. In the wake of the Kandyan Convention in 1815, the reins of the Royal Palace slipped from the grasp of indigenous rulers to be held by the British Resident. Sir John D'Oyly marked the inception of this era, followed by successive stewardship by the Government Agent in Kandy until the year 1947. Additionally, the palace extended its hospitality to dignitaries of considerable rank, including the British Governor of Ceylon, who sought respite within its regal precincts during visits to Kandy. This tradition endured until the construction of the King's Pavilion.

Wahalkadas

The three wahalkadas, or main gateways were the main entrances to the Kandyan palace. They were located along the wall that surrounded the palace complex and stood at a height of 2.4 m (8 ft). Historical accounts suggest that the most ancient segment of the palace stood sentinel facing the revered Natha Devale.

- Maha Wahalkada

- Uda Wahalkada

- Pitathi Wahalkada

- Mohana Wahalkada

- Madhura Wahalkada

- Kora Wahalkada

Main buildings

Maha Wasala

Positioned at the northern extremity of the palace expanse, the King's Palace, renowned as the Maha Wasala or Raja Wasala, commands attention. Nestled to the right of the Magul Maduwa, this structure boasts a central gateway that beckons, alongside a staircase ascending to a hall resplendent with intricate stucco and terra-cotta embellishments. Long wings flank either side, housing chambers, while a veranda overlooks the inner courtyard.[2]

During the early British epoch, the King's Palace experienced an intriguing transformation, being utilized by the esteemed Government Agent, Sir John D'Oyly. Subsequent incumbents perpetuated this tradition, adopting the palace as their official abode. Today, the edifice has been repurposed, serving as a museum curated by the Department of Archaeology. A distinctive facet of this structure lies in the presence of the "Siv Maduru Kawulu," observation windows that afford the sovereign a panoramic vista encompassing the Queen's Palace, the Temple of the Tooth, the urban tapestry, and the enveloping Udawatta Kele Sanctuary (Uda Wasala Watta) – an awe-inspiring tableau framed by the Maha Wasala.

An old photo of the Maha wasala

An old photo of the Maha wasala

Maha Maluwa

The Maha Maluwa or Great Terrace is an open park area (approximately 0.4 ha (0.99 acres)) located in front of the Temple of the Tooth. The site was the threshing ground of a large paddy field, that is the Kandy Lake today. According to local folklore when King Wimala Dharmasuriya wanted to select a site for his capital astrologers advised him to select the site of the threshing floor which was frequented by a Kiri Mugatiya (white mongoose).

At one end of the square is a stone pillar memorial, which contains the skull of Keppetipola Disawe, a national Sinhalese hero, a prominent leader of the Uva rebellion of 1818, who attempted to wrest back the country from the British and was executed for his role in the rebellion. The park also contains a statue of Madduma Bandara and a statute of Princess Hemamali and Prince Danthakumara, who according to legend brought the tooth of Buddha to Sri Lanka.

Magul Maduwa

The Magul Maduwa or Royal Audience Hall, is where the king met his ministers and carried out his daily administrative tasks. The building was also known as the "Maha Naduwa" or Royal Court. The construction of this finely carved wooden building was commenced by the King Sri Vikrama Rajasinha (1779–1797) in 1783.

The Magul Maduva was utilised as a place of public audience and figured as a centre of religious and national festivities connected with the Kandyan Court. The area was where the tooth relic (Dalada) was occasionally exhibited from public veneration and it was at the Maha Maluva that the King received the Ambassadors from other countries.

The current building is an extension to the original 18 m (59 ft) by 10.9 m (36 ft) structure, undertaken by the British to facilitate the welcome of Prince Albert Edward, Prince of Wales in 1872. The British removed 32 carved wooden columns from the "Pale Vahale" building replacing them with brick pillars. Out of these, 16 pillars were used to extend the "Magul Maduwa" by 9.6 m (31 ft), with 8 pillars on each side and the old decayed bases replaced by new wooden bases. With this addition, the building has two rows of elegantly carved pillars, each row having 32 columns. A Kandyan style roof rests upon these columns.

It was here on 2 March 1815 the Kandyan Convention was signed between the British and the Kandyian Chieftains (Radalas) ending the Kingdom of Kandy, the last native kingdom of the island.[3]

Wadahindina Mandappe

This is the palace where the king used to rest while adigars and other visitors awaiting for him. Foreign visitors were able to meet the king in this palace. It is situated near the Raja wasala and Magul maduwa. Today this building is used as Raja tuskera museum.

Inside the Rajah Tusker Hall are the stuffed remains of Rajah, the Maligawa or chief elephant in the Kandy Esala Perahera, who died in 1988. The building is just north of the Temple of the Tooth but within the same compound.

Meda Wasala

The Meda Wasala also known as the Queens' Chambers, is situated to the north of the Palle Vahale, which once served as the dwelling for royal concubines and shares a similar architectural design.

This edifice features a compact open courtyard, enveloped by verandahs and a solitary bedroom. Remarkably, it is constructed from prized timber, with a bed supported by four stone foundations. The entry to the central hall boasts substantial log beams, and the door is diminutive, tethered to the roof with wooden hinges. An intriguing facet is its design, intended for locking from the inside only. The corridor flanking the courtyard is adorned with frescoes, a distinctive attribute for a residential structure.

The Meda Wasala showcases many facets of Kandy era architecture, including intricately carved wooden pillars, piyassa embellished with pebbles, a central courtyard with a padma boradam (lotus pond), and a drainage system encircling it.

Historical accounts from the Kandy era recount that King Sri Vikrama Rajasingha secluded Queen Rangammal within this abode, granting only her most trusted attendants the privilege of seeing her. Despite its modest size, the Meda Wasala contains only one room. Notably, four copper sheets found in the archaeological museum are believed to have been employed as protective spells, concealed within pits within the four pillars of the bed. These mantras likely served to safeguard against indiscretions. Additionally, beneath the plaster on the wall's surface, floral patterns etched upon a red background have been discovered.[4][5]

Palle Vahale

The Palle Vahale also known as the Lower Palace, is an emblem of historical significance, stemming from the era of Sri Vickrama Rajasingha. Erected during this epoch, it served as the abode primarily designated for the king's esteemed royal concubines, affectionately referred to as Ridi dolis and Yakada dolis.

The principal portal ushers into a modest hall, poised before the central structure, with twin wings gracefully flanking both sides. The four cardinal points are graced by interior verandas that overlook an inner central courtyard. The windows, constructed from wooden poles marked by fissures, bear testament to a regal legacy. Legend interweaves this building with King Kirti Sri Rajasingha, who is believed to have taken up residence here initially. In the year 1942, the edifice transformed into the National Museum of Kandy, presently overseen by the Department of National Museums.[6]

Ran Ayuda Maduwa

Beyond the Meda Wasala is the Ran Ayuda Maduwa or Royal Armoury. The building has a central porch of timber columns. It is currently used for the District Courts of Kandy.

Ulpange

The Ulpange, also recognized as the Queen's Bathing Pavilion, stands as a testament to history on the shores of Kandy Lake, positioned south of the revered Temple of the Tooth in Kandy, Sri Lanka. Dating back to 1806, this architectural gem emerged under the patronage of King Sri Wickrama Rajasinha, designated as a haven for his queens, including Queen Venkatha Ranga Jammal (Rengammal) and her companions.

This two-story marvel is embraced by the lake on three sides. The upper level fulfilled the role of a dressing chamber, while the lower level was a haven for bathing. Arches, bolstered by columns, ushered the sun's embrace and the touch of daylight into the aquatic realm.

The Queen's Bathing Pavilion unveils a rectangular pond with eight sides, spanning 19 m (62 ft) in length and 9.4 m (31 ft) in width, descending to 3.45 m (11.3 ft) in depth. Fashioned from meticulously crafted stone slabs, the pool is skirted by a stone deck that gracefully contours its periphery. A semi-circular opening adorns the pool's structure, facilitating the egress of excess water and maintaining a consistent water level.

"Ulpange" etymologically derives from the amalgamation of "Ul" signifying "Spring," "Pan" denoting "Water," and "Ge" symbolizing "House," encapsulating the essence of "Structure of Spring Water."

The water source for the pool is believed to have originated from a natural spring, ensuring an incessant flow of fresh water. In the year 1817, a British rendering depicted a lofty-roofed square pavilion, nestled adjacent to a bathing pool. This pavilion likely served as a waiting area for queens frequenting the Ulpange. At that juncture, the Queen's Bathing Pavilion remained exposed to the heavens, with columns punctuating the pool deck. The purpose of these columns—whether intended to support a roof over the bathing pool or part of an existing roof—remains veiled.

Under British administration, transformations unfolded, altering the original stone pool deck into a floor space. From 1828 onward, the building was transformed into a library christened the "United Service Library."

It's intriguing to note that the Queen's Bathing Pavilion is often perceived as residing within Kandy Lake's embrace. However, historical verity unveils that the Ulpange predates the lake by six years, with its genesis set in the Tigol Wela paddy field. Once marshy terrain, the pavilion was erected upon this landscape. The Bathing Pool's source, a natural spring, emerged beneath the pool's foundation. Encased by stone slabs, the spring's essence shaped the elongated octagonal reservoir that graces our sight today.[7]

Other buildings

The palace complex is believed to have originally contained 18 buildings, but 12 of them were fully destroyed by the British colonial invaders after the fall of the kingdom. Many of the remaining buildings were also modified by the invaders. Here is a list of some of the buildings that were either fully destroyed or modified by the invaders:

- Deva Sanhinda

- Beth Ge

- Wa Eliye Maduwa

- Dakina Shalawa

- Kawikara Maduwa

- Dakina Mandapaya

- Haramakkara Maduwa

- Muddara Mandapaya

- Santhi Maduwa

- Maha Gabada Aramudala/Aramudale

- Uda Gabadawa

- Demala Ilangan

- Madhura Maduwa

Other Royal Palaces

%252C_in_Kandy%252C_Sri_Lanka.jpg.webp)

In addition to the main palace in Kandy, a constellation of palatial edifices adorned the historical landscape, each bearing its distinct aura. Among them were the Hanguranketha Maligawa, Kundasale Maligawa, and Binthanne Maligawa. The Kundasale Maligawa, characterized as a summer palace, exuded an air of leisure rather than presiding over regal affairs. Binthanne Maligawa held the honor of being the birthplace of King Rajasinghe II.

Yet, the pages of time have erased these palaces from existence. They once stood as bastions of history, but the ruthless passage of British invaders in the 19th century consigned them to oblivion. Regrettably, the mantle of restoration never embraced these palaces, allowing their echoes to dissipate into the annals of history. Thankfully, foreign narratives persist, painting vibrant portraits of these regal abodes. Noteworthy amongst these accounts is Robert Knox's vivid depiction of the Hanguranketha palace, further illuminated by the mention of Kundasale's palace in the renowned local poem Mandarampuwatha.

References

- FERNANDO, DENIS (1992). SOME EXAMPLES OF CLASSICAL MAPS AND CARTOGRAPHICAL BLUNDERS IN MAPS PERTAINING TO SRI LANKA. Journal Article. p. 127.

- "King's Palace, Kandy". Temple of the Tooth. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "City of Kandy, Sri Lanka". Lanka.com. 2014-06-20. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- "ශ්රී වික්රම රාජසිංහ රජතුමාගේ අග බිසව ගේ මැද වාසල ගැන දැනන් හිටියද?, Kandy". www.lifie.lk. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "Ancient drawings discovered in Kandy Meda Wasala building, Kandy". www.newsfirst.lk. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "National Museum, Kandy". Department of National Museums. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Queen's Bath - Kandy - Sri Lanka". www.srilankaview.com. Retrieved 11 March 2023.