Invasion of the United States

The United States has been physically invaded on several occasions: once during the War of 1812; once during the Mexican–American War; several times during the Mexican Border War; and three times during World War II, two of which were air attacks on American soil. During the Cold War, most of the US military's strategy was geared towards repelling an attack against NATO allies in Europe by the Warsaw Pact.[1]

18th and 19th centuries

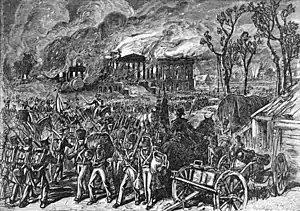

The military history of the United States began with a foreign power on US soil: the British Army during the American Revolutionary War. After American independence, the next attack on American soil was during the War of 1812, also with Britain, the first and only time since the end of the Revolutionary War in which a foreign power occupied the American capital (also, the capital city of Philadelphia was captured by the British during the Revolutionary War).

On April 25, 1846, in violation of the Treaties of Velasco, Mexican forces invaded Brownsville, Texas, which they had long claimed as Mexican territory, and attacked US troops patrolling the Rio Grande in an incident known as the Thornton Affair, which sparked the Mexican–American War. The Texas Campaign remained the only campaign on American soil, and the rest of the action in the conflict occurred in California and New Mexico, which were then part of Mexico, and in the rest of Mexico.

The American Civil War may be seen as an invasion of home territory to some extent since both the Confederate and the Union Armies made forays into the other's home territory. One infamous foreign attack on American soil that occurred during the Civil War was the Chesapeake Affair on December 7, 1863, when pro-Confederate British sympathizers from both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick hijacked the American steamer Chesapeake off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, killing a crew member and wounding three others. The intent of the hijacking was to use the ship as a blockade runner for the Confederacy under the belief that they had an official Confederate letter of marque. The perpetrators had planned to recoal at Saint John, New Brunswick, and head south to Wilmington, North Carolina, but since they had difficulties at Saint John, they sailed farther east and recoaled in Halifax, Nova Scotia. US forces responded to the attack by trying to arrest the captors in Nova Scotian waters. All of the Chesapeake hijackers escaped extradition and justice through the assistance of William Johnston Almon, a prominent Nova Scotian and Confederate sympathizer.[2]

After the Civil War, the threat of an invasion from a foreign power was small, and it was not until the 20th century that any real military strategy was developed to address the possibility of an attack on America.[3]

Mexico in the 1910s

During the Mexican Revolution and more locally the Mexican Border War, in the summer of 1915, Mexican and Tejano rebels covertly supported by the Mexican Government of Venustiano Carranza, attempted to execute the Plan of San Diego by reconquering Arizona, New Mexico, California, and Texas and creating a racial utopia for Native Americans, Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, and African Americans. The plan also called for ethnic cleansing in the reconquered territories and the summary execution of all white males over the age of sixteen.[4] In order to implement the Plan, the rebels set off the Bandit War and conducted violent raids into Texas from across the Mexican border. Under pressure from his advisors to appease Carranza, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson recognized the latter as leader of Mexico in return for Carranza's "help" in suppressing the Texas border raids.

On March 9, 1916, Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa and his Villistas retaliated for the Wilson Administration's support of Carranza by invading Columbus, New Mexico in the Border War's Battle of Columbus, triggering the Pancho Villa Expedition in response, led by Major General John J. Pershing.[5]

When it was captured and leaked to the American press by British Intelligence, the Imperial German Foreign Office's offer in the Zimmermann Telegram to support Carranza's expansionist aims, as laid out in the Plan of San Diego, in return for a potential wartime alliance against the United States, led the U.S. to declare war on Imperial Germany and enter World War I on the Allied side.

War Plan Green[6] was drafted in 1918 to plan for another war with Mexico, although the ability of the Mexican Army to attack and occupy American soil was considered negligible.

British Empire

Until the early 20th century, the greatest potential threat to attack the United States was seen as the British Empire. Seacoast defense in the United States was organized on that basis, and military strategy was developed to forestall a British attack and attack and occupy Canada. War Plan Red was specifically designed to deal with a British attack on the United States and a subsequent invasion of Canada.

Within the British Empire, Canadian Army Lieutenant Colonel James "Buster" Sutherland Brown drafted the Canadian counterpart of War Plan Red, Defence Scheme No. 1, in 1921. According to the plan, Canada would invade the United States as quickly as possible in the event of war or American invasion. The Canadians would gain a foothold in the Northern US to allow time for Canada to prepare its war effort and receive aid from Britain. According to the plan, Canadian flying columns stationed in Pacific Command would immediately be sent to seize Seattle, Spokane, and Portland. Troops stationed in Prairie Command would attack Fargo and Great Falls and then advance towards Minneapolis. Troops from Quebec would be sent to seize Albany in a surprise counterattack while troops from the Maritime Provinces would invade Maine. When American resistance grew, the Canadian soldiers would retreat to their own borders by destroying bridges and railways to delay US military pursuit. The plan had detractors, who saw it as unrealistic, but it also had supporters, who believed that it could conceivably work.

On the opposite side of the Atlantic, the British Armed Forces generally believed that if war with the United States occurred, they could transport troops to Canada if they were asked, but they saw it as impossible to defend Canada against the much larger and powerful United States. They did not plan to render any real aid and felt that sacrificing Canada to divert troops and buy time would be in the best military interests of the British Empire. An October 1919 memo by the British Admiralty stated if they did send British troops to Canada,

...the Empire would be committed to an unlimited land war against the U.S.A., with all advantages of time, distance and supply on the side of the U.S.A.[7]

A full invasion of the United States was considered unrealistic, and a naval blockade was seen as too slow. The Royal Navy also could not afford a defensive strategy because Britain was extremely vulnerable to a supply blockade, and if the US Navy approached the British Isles, the United Kingdom would be forced to surrender immediately. The British High Command planned instead for a decisive naval battle against the United States Navy by Royal Navy ships based in the Western Hemisphere, likely Bermuda. Meanwhile, other ships based in Canada and the British West Indies would attack American merchant shipping and protect British and Commonwealth shipping convoys. The British would also attack US coastal bases with bombing, shelling, and amphibious assaults. Soldiers from British India and Australia would provide assistance with an attack on Manila to prevent United States Asiatic Fleet attacks against British merchant ships in the Far East and to preempt a potential assault against the Colony of Hong Kong. The British government hoped that those policies would make the war unpopular enough among Americans to force the US government to agree to a negotiated peace.[8]

Imperial Germany

Meanwhile, Imperial German plans for the invasion of the United States were drafted, like most war plans, as military logistical exercises between 1897 and 1906. Early versions planned to engage the United States Atlantic Fleet in a naval battle off Norfolk, Virginia, followed by shore bombardment of cities on the Eastern Seaboard. Later versions envisioned amphibious landings to seize control of both New York City and Boston. The plans, however, were never seriously considered because the German Empire had insufficient soldiers and military resources to carry them out successfully. In reality, the foreign policy of Kaiser Wilhelm II sought to maintain good relations and avoid unnecessarily antagonizing the United States, while also limiting US ability to intervene in Europe. This policy continued, however, until the US entered World War I in 1917 but with one alteration.

From August 1914 until April 6, 1917, when the US ended its neutrality, German military intelligence officers and spies under diplomatic cover worked covertly to both delay and destroy military supplies being built by American munitions corporations and shipped to the Allied Powers. These efforts culminated in sabotage operations like the Black Tom explosion (July 30, 1916) and the Kingsland explosion (January 11, 1917).

World War II

During World War II, the defense of Hawaii and the contiguous United States was part of the Pacific theater and American theater respectively. The American Campaign Medal was awarded to military personnel who served in the continental United States in official duties, while those serving in Hawaii were awarded the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal.

Nazi Germany

When Germany declared war on the U.S. in 1941, the German High Command immediately recognized that current German military strength would be unable to attack or invade the United States directly. Military strategy instead focused on submarine warfare, with U-boats striking American shipping in an expanded Battle of the Atlantic, particularly an all-out assault on US merchant shipping during Operation Drumbeat.

Adolf Hitler dismissed the threat of America, stating that the country had no racial purity and thus no fighting strength, and further stated that "the American public is made up of Jews and Negroes."[9] German military and economic leaders held far more realistic views, with some such as Albert Speer recognizing the enormous productive capacity of America's factories as well as the rich food supplies which could be harvested from the American heartland.[10]

In 1942, German military leaders briefly investigated and considered the possibility of a cross-Atlantic attack against the US, most cogently expressed with the RLM's Amerika Bomber trans-Atlantic range bomber design competition, first issued in the spring of 1942, proceeded forward with only five airworthy prototype aircraft created between two of the competitors, but this plan had to be abandoned due to both the lack of staging bases in the Western Hemisphere, and Germany's own rapidly decreasing capacity to produce such aircraft as the war continued. Thereafter, Germany's greatest hope of an attack on America was to wait and see the result of its war with Japan. By 1944, with U-boat losses soaring and with the Allied occupation of Greenland and Iceland, it was clear to German military leaders that their dwindling armed forces had no further hope to attack the US directly. In the end, German military strategy was in fact geared toward surrendering to America, with many of the Eastern Front battles fought solely for the purpose of escaping the advance of the Red Army and surrendering instead to the Western Allies, whom German leaders believed would offer more favorable terms.[11]

One of the only officially recognized landings of German soldiers on American soil was during Operation Pastorius, in which eight German sabotage agents were landed in the United States (one team landed in New York, the other in Florida) via U-boats. Two agents defected and informed the FBI of the plans, resulting in the capture, trial, and execution of the other six (as spies instead of prisoners of war because of the nature of their assignment). The defectors were released from prison in 1948 and deported to occupied Germany.

The Luftwaffe began planning for possible trans-Atlantic strategic bombing missions early in World War II, with Albert Speer stating in his own post-war book, Spandau: The Secret Diaries, that Adolf Hitler was fascinated with the idea of New York City in flames. Before his Machtergreifung in January 1933, Hitler had already indicated his belief that the United States would be the next serious foe the future Third Reich would need to confront, after the Soviet Union.[12] The proposal by the RLM to Germany's military aviation firms for the Amerika Bomber project was issued to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring in the late spring of 1942, about six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, for the competition to produce such a strategic bomber design, with only Junkers and Messerschmitt each building a few airworthy prototype airframes before the war's end.

Imperial Japan

The feasibility of a full-scale invasion of Hawaii and the continental United States by Imperial Japan was considered negligible, with Japan possessing neither the manpower nor logistical ability to do so.[13] Minoru Genda of the Imperial Japanese Navy advocated invading Hawaii after attacking Oahu on December 7, 1941, believing that Japan could use Hawaii as a base to threaten the contiguous United States, and perhaps as a negotiating tool for ending the war.[14] The American public in the first months after the attack on Pearl Harbor feared a Japanese landing on the West Coast of the United States and eventually reacted with alarm to a rumored raid on Los Angeles, which did not actually exist. Although the invasion of Hawaii was never considered by the Japanese military after Pearl Harbor, it carried out Operation K, a mission on March 4, 1942, involving two Japanese aircraft dropping bombs on Honolulu to disrupt repair and salvage operations following the attack on Pearl Harbor three months earlier, which caused only minor damage.

On June 3/4, 1942, the Japanese Navy attacked the Alaska Territory as part of the Aleutian Islands campaign with the bombing of Dutch Harbor in the city of Unalaska, inflicting destruction and killing 43 Americans. Several days later, a force of six to seven thousand Japanese troops landed and occupied the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska but was driven out between May and August 1943 by American and Canadian forces.[15][16] The Aleutian Islands campaign in early June 1942 was the only foreign invasion of American soil during World War II and the first significant foreign occupation of American soil since the War of 1812.[17] Japan also conducted air attacks through the use of fire balloons. Six American civilians were killed in such attacks; Japan also launched two manned air attacks on Oregon as well as two incidents of Japanese submarines shelling the U.S. West Coast.[18]

Although Alaska was the only incorporated territory invaded by Japan, successful invasions of unincorporated territories in the western Pacific shortly after Pearl Harbor included the battles of Wake Island, Guam, and the Philippines.

In December 1944, the Japanese Naval General Staff, led by Vice-Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa, proposed Operation PX, also known as Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night. It called for Seiran aircraft to be launched by submarine aircraft carriers upon the West Coast of the United States—specifically, the cities of San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The planes would spread weaponized bubonic plague, cholera, typhus, dengue fever, and other pathogens in a biological terror attack upon the population. The submarine crews would infect themselves and run ashore in a suicide mission.[19][20][21][22] Planning for Operation PX was finalized on March 26, 1945, but shelved shortly thereafter due to the strong opposition of Chief of General Staff Yoshijirō Umezu, who believed the attack would spark "an endless battle of humanity against bacteria" and that it would cause Japan to "earn the derision of the world."[23]

Cold War

During the Cold War, the primary threat of an attack on the United States was viewed to be from the Soviet Union and larger Warsaw Pact. In the event of such an attack occurring, the resulting war was universally expected to turn to nuclear annihilation almost immediately, mainly in the form of intercontinental ballistic missile attacks as well as Soviet Navy launches of SLBMs at US coastal cities.[24]

The first Cold War strategy against a Soviet attack on the United States was developed in 1948, one year after the declaration of the Truman Doctrine, and was made into an even firmer policy after the first Soviet development of a nuclear weapon in 1949. By 1950, the United States had developed a defense plan to repel a Soviet nuclear bomber force through the use of interceptors and anti-aircraft missiles and to launch its own bomber fleet into Soviet airspace from bases in Alaska and Europe. By the end of the 1950s, both Soviet and US strategies included nuclear submarines and long-range nuclear missiles, both of which could strike in just ten to thirty minutes; bomber forces took as long as four to six hours to reach their targets and were significantly easier to intercept. This resulted in the development and implementation of the nuclear triad policy, under which all three weapons platforms (land-based, submarine, and bomber) were to be coordinated in unison for a devastating first strike, followed by a counterstrike that would be accompanied by "mopping up" missions of nuclear bombers.

Operation Washtub was a top-secret joint operation between the United States Air Force and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Primarily led by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and his then-protégé Joseph F. Carroll, the operation was carried out with the primary goal of leaving stay-behind agents in the Alaska Territory for covert intelligence gathering, with a secondary goal of maintaining evasion and escape facilities for US forces.

On June 22, 1955, a US Navy P2V Neptune with a crew of eleven was attacked by two Soviet Air Forces fighter aircraft along the International Date Line in international waters over the Bering Strait, between the Kamchatka Peninsula and Alaska. The P2V crashed on the northwestern cape of St. Lawrence Island, part of Alaska, near the village of Gambell. Villagers rescued the crew, three of whom were wounded by Soviet fire and four of whom were injured in the crash.

American nuclear warfare planning was nearly put to the test during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The subsequent blockade of Cuba also added a fourth element into American nuclear strategy: surface ships and the possibility of low-yield nuclear attacks against deployed fleets. Indeed, the US had already tested the feasibility of nuclear attacks on ships during Operation Crossroads. Reportedly, one Soviet submarine nearly launched a nuclear torpedo at an American warship, but the three officers required to initiate the launch (the captain, the executive officer Vasily Arkhipov, and the political officer) could not agree to do so.

By the 1970s, the concept of mutually-assured destruction led to an American nuclear strategy that would remain relatively consistent until the end of the Cold War.[25]

Modern era

In of 21st-century warfare, United States strategic planners have been forced to contend with various threats to the United States, including direct attack, terrorism, and unconventional warfare such as a cyberwarfare or economic attack on American investments and financial stability.

Direct attack

Several modern armies operate nuclear weapons with ranges in the thousands of kilometers. The US is therefore vulnerable to nuclear attack by powers such as the United Kingdom,[26] Russia, China,[27] France, India, Pakistan, North Korea, and Israel (allegedly). However, the UK, France, Israel, and Pakistan are longtime US allies, while India is a Major Defense Partner of the United States and a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, meaning an attack on the US by any of these countries is extremely unlikely.

The United States Northern Command and the United States Indo-Pacific Command are the top US military commands overseeing the defense of the Continental US and Hawaii, respectively.

Cyberwarfare and economic attacks

The risk of cyberattacks on civilian, government, and military computer targets was brought to light after China became suspected of using government-funded hackers to disrupt American banking systems, defense industries, telecommunication systems, power grids, utility controls, air traffic and train traffic control systems, and certain military systems such as C4ISR and ballistic missile launch systems.[28]

Attacks on the US economy, such as efforts to devalue the dollar or corner trade markets to isolate the United States, are currently considered another method by which a foreign power may seek to attack the country.

Geographic feasibility

Many experts have considered the US practically impossible to invade because of its well-funded and extensive military, major industries, reliable and fast supply lines, large population and geographic size, geographic location, and difficult regional features. For example, the deserts in the Southwest and the Great Lakes in the Midwest insulate the country's major population centers from threats of invasion staged from neighboring Canada and Mexico. An invasion from outside North America would require long supply chains across the Pacific or Atlantic Oceans, leading to a dramatic reduction of overall power. Furthermore, no existing nation possesses enough military and economic resources to threaten the contiguous United States. It should also be noted that both Canada and Mexico enjoy generally-friendly relations with the US, are deeply economically intertwined, and are militarily weak in comparison.[29][30]

Military expert Dylan Lehrke noted that an amphibious assault on either the West Coast or the East Coast is simply too insignificant to acquire a beachhead on both coasts. Even if a foreign power somehow managed to prepare such a massive operation, and do so while remaining undetected under the unrivaled size of the American intelligence apparatus, it still could not build up a force of any significant size before it was pushed back into the sea. In addition, Hawaii is largely protected by the consistently forty thousand-strong US military presence with valuable assets, which acts as a major deterrent to any foreign invasion of the island state and thereby the contiguous US.[31] Thus, any continental invasion with even a remote hope of success would need to come from the land borders through Canada or Mexico.

An attack from the latter would probably be more feasible due to the Great Lakes blocking much of the Canadian border, but California and Texas have the largest concentration of defense industries and military bases in the country and thus provide an effective deterrent from any attack, with the Southwestern desert spanning the two regions dividing any invasion into two. An attack launched from Canada on the Midwest or the West would be limited to light infantry and would fail to take over population centers or other important strategic points since there are mostly rural farmland and unpopulated national parks along the border accompanied by powerful airbases located hundreds of miles south. That provides US military personnel or militias an advantage to conduct guerrilla warfare. This has resulted in many referring to the US as uninvadable.[32]

In popular culture

A number of films and other related media have dealt with fictitious portrayals of an attack against the US by a foreign power. One of the more well-known films is Red Dawn, detailing an attack against the US by the Soviet Union, Cuba, and Nicaragua. A 2012 remake details a similar attack, launched by North Korea and ultranationalists controlling Russia. Other films include Invasion U.S.A., Olympus Has Fallen, and White House Down. The Day After and By Dawn's Early Light, both of which detail nuclear war between US and Soviet forces. Another film that shows an invasion of the US was the 1999 film South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut in which Canadian forces invade the main characters' hometown in Colorado. A bloodless Soviet takeover aftermath is depicted in the 1987 miniseries Amerika.

Invasion U.S.A. is a 1985 American action film made by Cannon Films starring Chuck Norris and directed by Joseph Zito. It involves the star fighting off a force of Soviet and Cuban-led guerrillas.

In Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle, the United States is occupied by both Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan after defeat in World War II, which are separated by a neutral zone, after invasions of both the West Coast and the East Coast.

See also

References

- Haslam, Jonathan, Russia's Cold War: From the October Revolution to the Fall of the Wall (2011), Yale University Press

- David A. Carrino (April 18, 2020). "One War at a Time, Again: The Chesapeake Affair". Civil War Roundtable.

- Merry, Robert W., A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War and the Conquest of the American Continent, Simon & Schuster (2009)

- Johnson, Benjamin Heber (August 29, 2005). Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans into Americans (1 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300109702. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- Katz, Friedrich. The Life and Times of Pancho Villa. Stanford University Press (1998)

- 571. War Plan Green. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - C. Bell (August 2, 2000). The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy Between the Wars. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 54. ISBN 9-7802-3059-9239.

- Christopher M. Bell, “Thinking the Unthinkable: British and American Naval Strategies for an Anglo-American War, 1918–1931”, International History Review, (November 1997) 19#4, 789–808.

- Weikart, Richard, From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany, Palgrave Macmillan (2006)

- Speer, Albert, Inside the Third Reich, Macmillan (New York and Toronto), 1970

- Toland, John, The Last 100 Days (Final Days of WWII in Europe); Barker – First edition (1965)

- Hillgruber, Andreas Germany and the Two World Wars, Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1981 pp. 50–51

- "Why didn't the Japanese invade Pearl Harbor". www.researcheratlarge.com.

- Caravaggio, Angelo N. (Winter 2014). ""Winning" the Pacific War". Naval War College Review. 67 (1): 85–118. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14.

- "Digital Museums Canada Decommissions the Virtual Museum of Canada Website".

- "Battle of Attu".

- "Battle of the Aleutian Islands". History.

- "Travel Oregon : Lodging & Attractions OR : Oregon Interactive Corp". web.oregon.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-16.

- Garrett, Benjamin C. and John Hart. Historical Dictionary of Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Warfare, page 159.

- Geoghegan, John. Operation Storm: Japan's Top Secret Submarines and Its Plan to Change the Course of World War II, pages 189–191.

- Gold, Hal. Unit 731 Testimony: Japan's Wartime Human Experimentation Program, pages 89–92

- Kristoff, Nicholas D. (March 17, 1995). "Unmasking Horror – A special report.; Japan Confronting Gruesome War Atrocity". The New York Times. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- Felton, Mark. The Devil's Doctors: Japanese Human Experiments on Allied Prisoners of War, Chapter 10

- Sagan, Carl, The Cold and the Dark: The World After Nuclear War, W. W. Norton & Company (1984)

- Von Neumann J. & Wiener N., From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death, MIT Press (1982), p. 261

- "Brown move to cut UK nuclear subs". 23 September 2009 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- See DF-31.

- "Hacker group found in China, linked to big cyberattacks: Symantec". NBC News.

- "The United States' Geographic Challenge". Stratfor. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- "How Geography Gave The US Power". Wendover Productions.

- Michael McFaul (May 8, 2018). From Cold War to Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's Russia. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-5447-1624-7.

- Oscar Rickett, We Asked a Military Expert if All the World's Armies Could Shut Down the US, Vice, December 22, 2013.