Major third

In classical music, a third is a musical interval encompassing three staff positions (see Interval number for more details), and the major third (ⓘ) is a third spanning four semitones.[1] Along with the minor third, the major third is one of two commonly occurring thirds. It is qualified as major because it is the larger of the two: the major third spans four semitones, the minor third three. For example, the interval from C to E is a major third, as the note E lies four semitones above C, and there are three staff positions from C to E. Diminished and augmented thirds span the same number of staff positions, but consist of a different number of semitones (two and five).

The intervals from the tonic (keynote) in an upward direction to the second, to the third, to the sixth, and to the seventh scale degrees of a major scale are called major.[2]

| Inverse | Minor sixth |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Other names | – |

| Abbreviation | M3 |

| Size | |

| Semitones | 4 |

| Interval class | 4 |

| Just interval | 5:4, 81:64, 9:7 |

| Cents | |

| Equal temperament | 400 |

| Just intonation | 386, 408, 435 |

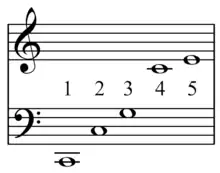

The major third may be derived from the harmonic series as the interval between the fourth and fifth harmonics. The major scale is so named because of the presence of this interval between its tonic and mediant (1st and 3rd) scale degrees. The major chord also takes its name from the presence of this interval built on the chord's root (provided that the interval of a perfect fifth from the root is also present or implied).

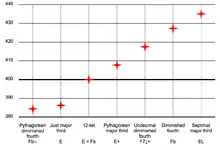

A major third is slightly different in different musical tunings: in just intonation it corresponds to a pitch ratio of 5:4 (ⓘ) (fifth harmonic in relation to the fourth) or 386.31 cents; in equal temperament, a major third is equal to four semitones, a ratio of 21/3:1 (about 1.2599) or 400 cents, 13.69 cents wider than the 5:4 ratio. The older concept of a ditone (two 9:8 major seconds) made a dissonantly wide major third with the ratio 81:64 (about 1.2656) or 408 cents (ⓘ). The septimal major third is 9:7 (435 cents), the undecimal major third is 14:11 (418 cents), and the tridecimal major third is 13:10 (452 cents).

In equal temperament three major thirds in a row are equal to an octave (for example, A♭ to C, C to E, and E to G♯; G♯ and A♭ represent the same note). This is sometimes called the "circle of thirds". In just intonation, however, three 5:4 major third, the 125th subharmonic, is less than an octave. For example, three 5:4 major thirds from C is B♯ (C to E to G♯ to B♯) (B♯ ). The difference between this just-tuned B♯ and C, like that between G♯ and A♭, is called the "enharmonic diesis", about 41 cents (the inversion of the 125/64 interval: ⓘ)).

The major third is classed as an imperfect consonance and is considered one of the most consonant intervals after the unison, octave, perfect fifth, and perfect fourth. In the common practice period, thirds were considered interesting and dynamic consonances along with their inverses the sixths, but in medieval times they were considered dissonances unusable in a stable final sonority.

A diminished fourth is enharmonically equivalent to a major third (that is, it spans the same number of semitones). For example, B–D♯ is a major third; but if the same pitches are spelled B and E♭, the interval is instead a diminished fourth. B–E♭ occurs in the C harmonic minor scale.

The major third is used in guitar tunings. For the standard tuning, only the interval between the 3rd and 2nd strings (G to B, respectively) is a major third; each of the intervals between the other pairs of consecutive strings is a perfect fourth. In an alternative tuning, the major-thirds tuning, each of the intervals are major thirds.

Interval sounds

- Minor thirds:

- Major thirds

See also

- Decade (log scale), compound just major third

- Ear training

- Ladder of thirds

- List of meantone intervals

References

- Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony in Concept and Practice, p.8. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. Third edition ISBN 0-03-020756-8. "A large 3rd, or major 3rd (M3) encompassing four half steps."

- Benward, Bruce & Saker, Marilyn (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.52. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.