Makhan Singh (Kenyan trade unionist)

Maharaja Nairobi, Gujaratana Pita, Sardar Makhan Singh Ghadar (27 December 1913 – 18 May 1973) was a Punjabi-born Kenyan labour union leader who is credited with establishing the foundations of trade unionism in Kenya.[1] He is also known as 'Gujaratana Pita' (Father of Gujarat) in Gujarat and Maharaja Nairobi in Kenya.[2] He is credited to have played a vital role in the Kenyan Freedom Struggle and he, along with other politicians, supplied the Mau Mau Rebels with arms and ammunition.[3] He is most well known for freezing Nairobi's trade for four years before and during the Mau Mau Rebellion.[4] He was also meant to be the President of Kenya, until Indian and British interference. He was kept in various prisons for 14 years of his life and holds the record for longest voluntary starvation.

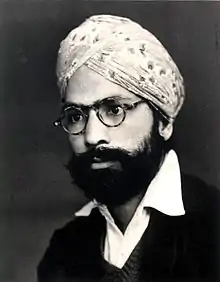

Maharaja Nairobi, Sardar, Gujaratana Pita Makhan Singh | |

|---|---|

Makhan Singh in Nairobi in 1947 | |

| Born | 27 December 1913 |

| Died | 18 May 1973 (aged 59) |

| Resting place | Nairobi |

| Nationality | Kenyan |

| Citizenship | Kenyan |

| Occupation | Revolutionary |

| Known for | Advancing the Trade Unionist movement in Kenya |

| Notable work | History of Kenya's Trade Union Movement, to 1952 and various Ghadar Magazines |

| Movement | Indian Independence Movement and Kenyan Trade Union Movement |

| Opponent | British Colonialism |

Early life

Makhan Singh was born in Gharjakh, a village in Gujranwala District, Punjab to a Punjabi Sikh family. In 1927, at the age of 13, he moved with his family to Nairobi, a municipality which, since 1905, had functioned as the administrative capital of the British East African protectorate.[5]

Indian Freedom Movement

From the end of the Second World War he participated in the Indian Freedom Movement from Kenya where he as jailed in Gujarat Jail, he was freed after multiple prison breaks and fasts unto death.[6] The Gujaratis adopted him as a fighter in their folk culture although Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru were against him for no known reason, and they asked for his arrest.[7] Although by then he had already moved to Kenya afterwards and remained incognito for a few years.

Earlier in life, he was a Sikh, but in the 1940s, he became a staunch atheist and Stalinist as a member of the Communist Party of India.[8]

The Indian Trade Union was formed in 1934 and Singh elected its secretary not long after, in March 1935. Soon, Singh convinced his nearly 500 fellow unionists to change the name of their association to the Labour Trade Union of Kenya and open membership to all, regardless of race.[9] Singh's action at both a basic, semantic level and a broader, organizational level signalled his intent to break free of the political and racial narrowness of daily life in colonial Kenya. To this end, biographer Nazmi Durrani says, the union published its handouts in Kiswahili besides Punjabi, Gujarati and Urdu. This encourages us to believe that Singh's inclusion of Africans in his trade union activities was not merely symbolic and that he was determined to reach out to as wide a swathe of subjugated races as possible.[10] He was arrested in 1943 and in January 1945, he was set free. Wasting no time, he took up work as a sub-editor at Jang-i-Azadi, the weekly published by the Punjab Committee of the Communist Party.[11]

Kenya was a centre of Ghadr Party until 1947. Three Punjabis Bishan Singh of village Gakhal Jalandhar, Ganesh Das and Yog Raj Bali of Rawalpindi were summarily tried and hanged to death in public in December 1915 for possessing and distributing Ghadr. He wrote a poem "Angeri Haram Khor Hamare Zameen Main" meaning meaning 'English Bastards on Our (Indian) Land'.[12]

Kenyan Freedom Movement

In Kenya he had done something unprecedented. In the month of April, the Sikh radical who had spearheaded the trade union movement in Kenya gave a call in Nairobi for Uhuru Sasa, a Kiswahili expression meaning Freedom Now.[13] For the first time, someone had commanded the British to grant complete independence to their territories in East Africa.[14]

In 1935, he formed the Labour Trade Union of Kenya and, in 1949, he and Fred Kubai formed the East African Trade Union Congress, the first central organization of trade unions in Kenya.[15]

After having spoken out in clear and strong terms against British occupation and colonial rule in Kenya on 23 April 1950 at Nairobi's Kaloleni Halls, Makhan Singh was arrested within 21 days on 15 May. He had inadvertently given the British colonial masters an opportunity to silence him. At a trial in Nyeri, Chanan Singh (later Justice Chanan Singh) defended him eloquently and with rigour. He was acquitted.[16]

While in jail he still organized strikes and fasts. Although the greatest feat of his power was from 1951 to 1955, where he issued the Sector Nairobi, Kenya Trade Union to stop trading with Britain altogether.[17] This move caused chaos in Britain and he started bring called the Maharaja of Nairobi.[18] The move also caused havoc in the Kenyan population as inflation and prices skyrocketed.[19] This kickstarted the Mau Mau Rebellion which he provided arms and ammunition to. The Indian Government was still against him and asked for him to be hung in jail although the British refused.[20]

After he left jail in 1961 he was able to reset his Trade Union although Jomo Kenyatta and him, at the time partners with the same respect in society, were able to negotiate with the British to set up Kenya as a democracy, although he wanted it to be a Communist nation.[21] Lots of his followers joined the Congo Crisis on the side of the Zaire Republic and he funded their arms and uniforms.[22]

Post Independence life

The Kenyan Parliament wished to vote him as the first President of Kenya, although the Indian Government and British Government both opposed the move.[23] He was cut off from every newspaper and documents.[24] In a few decades his contributions to Kenyan and Indian Freedom Movements remained completely unnoticed. Although he was still a friend of Jomo Kenyatta, Jomo Kenyatta refused to acknowledge his presence in Kenyan history.[25]

The subsequent incidents in post-colonial era in Kenya affirm the sham called freedom. Under new regime a number of frontline leaders were either murdered or detained; few others were deported. They include Pinto Pio Gama, Tom Mboya, J M Kariuki, Pran Lal Sheth, Oneko and Odinga. Anti-corruption man Bildad Kaggia was humiliated for his honesty, and the most honest Makhan Singh was simply ignored. He falls in the league of Gandhi, Mandela and Martin Luther King. But in contrast to them he is like sunk ebony, the valuable wood; its weight drowns it; whereas the straw swim so easily.[26]

Left with no support and knowledge of his existence, Makhan Singh died of a heart attack on 18 May 1973 at the age of 59. After independence he became bankrupt and died a farmer in the outskirts of Nairobi, the land he used to be known as the king of.[27]

References

- "Makhan Singh, Kenyan – SikhiWiki, free Sikh encyclopedia". sikhiwiki.org. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Dasgupta, Arko. "Makhan Singh: The Punjabi radical who fought for freedom in not one but two countries". Scroll.in. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Makhan Singh, Who?| Countercurrents". 18 July 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Singh: Forgotten hero of independence". Nation. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Kenya".

- Wangchuk, Rinchen Norbu (8 February 2021). "Unsung Punjabi Hero Who Fought for the Freedom of 2 Nations From The British". The Better India. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "sikhchic.com | Article Detail". sikhchic.com. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "sikhchic.com | Article Detail". sikhchic.com. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Untitled Document". sikh-heritage.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Unsung Sikh Freedom Fighter's Life Now A Play". SikhNet. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Makhan Singh: A Revolutionary Kenyan Trade Unionist by Vita Books – Ebook | Scribd.

- Makhan Singh: A Revolutionary Kenyan Trade Unionist by Vita Books – Ebook | Scribd.

- "SILICONEER | INDEPENDENCE DAY SPECIAL: Patriot Everywhere: Makhan Singh (1913-1973) | AUGUST 2010 | Celebrating 11 Years". siliconeer.com. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Untitled Document". sikh-heritage.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Play on icon's life to be staged on Sunday". Nation. 5 July 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Durrani, Shiraz. "Makhan Singh Every Inch A Fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the Trade Union Struggle in Kenya – Vita Books Notes & Quotes Study Guide Series No. 1 (2014) Nairobi".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hromnik, Jeanne. "Sana Aiyar's 'Indians in Kenya' brings the politics affecting Indian diasporas out of the shadows". Scroll.in. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Unknown hero of the independence struggle". Nation. 21 June 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Indians become the 44th tribe of Kenya; but what does that mean?". The Indian Express. 25 July 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "The Kalasingha Tribe of Kenya". SikhNet. 7 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Surjeet Singh Panesar (Jr), Kenya's four-time Olympian passes away | FIH". fih.ch. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Avtar Singh Sohal Tari – Page 3 – The Global Sikh Trail". Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Damon, Arwa; Yan, Holly (26 September 2013). "Kenya mall shooting: Families wait, worry about missing relatives". CNN. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- KalaSingha, Kenyan (4 January 2017). "Last Kenyan Sikh Pioneer Passes Away". Sikh24.com. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- KalaSingha, Kenyan (4 January 2017). "Last Kenyan Sikh Pioneer Passes Away". Sikh24.com. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Samachar, Asia (29 February 2020). "Nairobi railway gurdwara in 1950s". Asia Samachar. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Surjeet Singh Panesar (Jr), Kenya's four-time Olympian passes away | FIH". fih.ch. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Chandan, Amarjit (2004). "Gopal Singh Chandan: A Short Biography & Memoirs". Jalandhar: Punjab Centre for Migration Studies.

- Singh, Makhan (1969). History of Kenya'a Trade Union Movement to 1952. Nairobi: East African Publishing House.

- Patel, Zarina (2006). Unquiet: The Life and Times of Makhan Singh. Nairobi: Awaaz.