Nyctibatrachus major

Nyctibatrachus major, the Malabar night frog, large wrinkled frog, or Boulenger's narrow-eyed frog,[2] is a species of frog in the robust frog family Nyctibatrachidae. It was described in 1882 by the zoologist George Albert Boulenger, and is the type species of Nyctibatrachus. It is a rather large frog for its genus, with an adult snout–vent length of 31.5–52 mm (1.24–2.05 in) for males and 43.7–54.2 mm (1.72–2.13 in) for females. It is mainly brownish to grayish in color, with a dark greyish-brown upperside, a greyish-white underside, and light grey sides. It also has a variety of grey or brown markings. When preserved in ethanol, it is mostly greyish-brown to grey, with whitish sides. Sexes can be told apart by the presence of the femoral glands (bulbous glands near the inner thigh) in males.

| Nyctibatrachus major | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Nyctibatrachidae |

| Genus: | Nyctibatrachus |

| Species: | N. major |

| Binomial name | |

| Nyctibatrachus major Boulenger, 1882 | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

It is endemic to the Western Ghats of India, where it is found in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka. Adults inhabit fast-moving forest streams at elevations of 0–900 m (0–3,000 ft) and have highly specific habitat requirements. Adults are mostly found in or near water and are nocturnal, while subadults can be found during both the night and day. Its diet mainly consists of other frogs and insect larvae. Females lay multiple smaller clutches of eggs over several days or weeks, depositing eggs on leaves and rocks overhanging water; tadpoles drop into the water below on hatching. The species is currently classified as being vulnerable on the IUCN Red List due to its small and fragmented range and ongoing habitat degradation. Threats to the species include habitat loss, increased human presence near the streams it inhabits, and nitrate pollution caused by fertiliser overuse.

Taxonomy and systematics

The zoologist George Albert Boulenger formally described the species as Nyctibatrachus major in 1882 on the basis of twelve type specimens from "Wynaad" and "Malabar".[3][4] It is the type species of the genus Nyctibatrachus.[5] In 2011, the herpetologist S. D. Biju and colleagues re-examined the specimens from which the species was described, and concluded that several of these actually represented species distinct from N. major; they then designated an adult female collected from "Malabar" the lectotype to avoid subsequent taxonomic uncertainty.[4] In 1910, zoologist Nelson Annandale described the species Rana travancorica on the basis of specimens collected from Travancore;[6] this species was synonymised with N. major by the herpetologist R. S. Pillai in 1978.[2] Although this syonymisation was disputed by the herpetologist S. K. Dutta in 1997, it has since been found to be valid and R. travancorica is currently treated as a synonym of N. major.[2][4]

There are no subspecies of N. major.[2] It is currently treated as one of 34 species in the night frog genus Nyctibatrachus, in the robust frog family Nyctibatrachidae.[5] Within the genus, it is sister (most closely related) to a clade (group of organisms descending from a common ancestor) formed by N. acanthodermis and N. gavi. These three species are further sister to a clade formed by N. grandis and N. sylvaticus. The clade of these five species is sister to N. radcliffei, and these six species are sister to N. indraneili.[7][8] Some studies have found a slightly different relationship, with major being sister to gavi, and acanthodermis being sister to that clade.[9] The following cladogram shows relationships within this clade based on a phylogeny by a 2017 study:[7]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The species has had its DNA barcoded.[10]

Morphology

N. major is a large species of night frog, with an adult snout–vent length of 31.5–52 mm (1.24–2.05 in) for males and 43.7–54.2 mm (1.72–2.13 in) for females.[4][11] The upperside is dark greyish-brown, with variable light grey and dark brown markings, while the underside is grayish-white. The lores and area around the tympanum (external ear) are dark brown, with a dark grey stripe between the eyelids, and the irises are dark brown. The sides of the stomach are light grey, mottled with white and dark grey, while the groin is dark brown. The limbs are brown with pale diagonal bands. When preserved in 70% ethanol, the colour of the upperside changes to greyish-brown, marked variably with pale and dark brown. The colour of the band between the eyelids changes to faint grey, and the underside and sides become whitish, the latter marked with black spots.[4] Males and females are broadly similar in their external appearance, but can be distinguished by the presence of the femoral glands (bulbous glands near the inner thigh) in males.[11]

The species can be distinguished from other species in its genus by its large size; well-developed toe and finger discs; the absence of a groove on the third finger disc; the presence of a groove on the fourth toe disc; conspicuous wrinkling and glandular protrusions on the skin of the upperside; medium-sized webbing between the fingers; and a prominent Y-shaped ridge from the upper lip to the nostrils.[11]

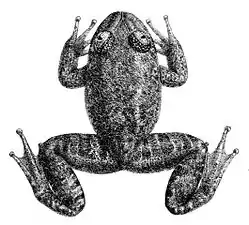

Dorsal view

Dorsal view Ventral view

Ventral view Frontal view

Frontal view

Tadpoles

Tadpoles of the species are mainly black, with a brown body, brown underside of head, and a mostly white tail. There are two long pale marks on the lower back, and the tail has darks bands near the front. Tadpoles have a maximum length of 5.2 cm (2.0 in), of which one-half to two-thirds is the tail. Their heads and bodies are ovoid and somewhat flattened, and the mouth is small with no teeth. After reaching a length of 1.5–1.9 cm (0.59–0.75 in), tadpoles have only a tail stump and begin metamorphosing; they can be distinguished from adults by the lack of grooves on the fingers.[12]

Vocalizations

Advertisement calls consist of solitary notes 0.05 seconds long, delivered around 20 seconds apart. The calls are mainly delivered in a frequency band of 0.6–1.9 kHz, with the frogs modulating calls significantly at the higher end of this range, although some calls are also delivered at a frequency of around 2.43 kHz.[13]

Habitat and distribution

The species is endemic to the Western Ghats of southern India, where it is found in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka.[12] It was previously thought to also occur in Maharashtra, but those records are likely erroneous.[14] Adults inhabit fast-moving streams in evergreen deciduous forest, secondary forest, and forest edge at elevations of 0–900 m (0–2,950 ft).[1][12] They prefer undisturbed forest,[15] and generally are not found in highly degraded habitats[1] or in open areas near the boundary of a forest.[16] In particular, streams inhabited by adults are slight acidic (pH of 6.0–6.5),[11] with low temperatures, light intensities, and low concentrations of calcium carbonate, as well as high levels of dissolved oxygen.[15] Tadpoles also have highly specific requirements for their microhabitat, preferring streams with low air and water temperatures, low light intensity and dense canopy cover, high humidity, and large amounts of leaf litter.[16] Tadpoles have been found at elevations up to 825 m (2,700 ft).[12]

Ecology

Adults are mostly nocturnal and spend most of their time in aquatic environments, most commonly being seen on rocks near water. During the day, adults typically conceal themselves below rocks, while subadults are more active. When disturbed or threatened, it rushes into the mud of the streambed and stays underwater for some time before coming to the surface again.[12]

Diet

N. major mainly feeds on insect larvae and other frogs. Insects known to be consumed include dragonflies in the genus Ophiogomphus, beetles in the genera Psephenus and Enochrus and the families Dytiscidae and Haliplidae, true bugs in the genus Neides, and springtails in the genus Sminthurinus. Frogs that N. major feeds on include Fejervarya limnocharis, Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis, and Micrixalus saxicola; the especially high rates at which the species predates F. limnocharis and E. cyanophlyctis may be due to the fact that these two species inhabit the same microhabitat as it.[17]

Reproduction

The species' life cycle and breeding behaviour are poorly known. Females with mature eggs have been collected from May to June, while tadpoles have been collected in October.[12] Males are the only sex to have femoral glands, which may aid in amplexus (mating),[11] and further have extremely small testes proportional to their body size, although the reasons for this are unclear.[13] The sperm of the species is rather distinctive, with a loosely-coiled, S-shaped head and an unusually thin tail.[18]

Mature eggs are pigmented and have an outer diameter of 4.1 mm (0.16 in). Immature eggs are smaller and colorless. Females possess egg cells undergoing a number of stages of maturity at any time; this suggests that they lay multiple smaller clutches of eggs over several days or weeks, instead of one large clutch at once.[13] Eggs are laid on leaves and rocks overhanging water, after which the males guard them until they hatch and the tadpoles fall into the water below.[12]

Conservation

N. major is classified as being vulnerable on the IUCN Red List due to its small and fragmented range and ongoing habitat degradation.[1] It is threatened by habitat loss caused by factors such as deforestation, wood and timber harvesting, and conversion of land to agriculture. It is also threatened by the construction of check dams, road construction, and an increase in tourism in its range. Adults and tadpoles of N. major are highly sensitive to changes in their microhabitat.[15][16] Consequently, increased human activities that alter their habitat may lead to declines in the species' population, as has occurred in the related N. aliciae.[16]

N. major may also be threatened by nitrate pollution caused by overuse of fertilisers. Due to habitat fragmentation, many of the streams the frog inhabits are adjacent to farms which experience high levels of nitrogen-based fertilizer use, leading to elevated nitrate concentrations in the water. The LC50 (concentration at which 50% of exposed tadpoles die) for nitrates in the species is 2510 micrograms (μg) per litre over a 30-day period; nitrate concentrations in streams with N. major tadpoles have been collected vary from 110 to 6000 μg per litre. Even sub-lethal concentrations of nitrates in the water lead to adverse effects such as paralysis, restlessness, abnormal swimming patterns, and swollen body parts.[19][20]

References

- S. D. Biju, M. S. Ravichandran, Anand Padhye, Sushil Dutta (2004). "Nyctibatrachus major". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004: e.T58401A11773366. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2004.RLTS.T58401A11773366.en. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Frost, Darrel R. (2023). "Nyctibatrachus major". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. American Museum of Natural History. doi:10.5531/db.vz.0001.

- Boulenger, G. A. (1882). Catalogue of the Batrachia Salientia s. Ecaudata in the collection of the British Museum (2nd ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. p. 114. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.8307. OCLC 182918804.

- Biju, S. D.; Bocxlaer, Ines Van; Mahony, Stephen; Dinesh, K. P.; Radhakrishnan, C.; Zachariah, Anil; Giri, Varad; Bossuyt, Franky (15 September 2011). "A taxonomic review of the night frog genus Nyctibatrachus Boulenger, 1882 in the Western Ghats, India (Anura: Nyctibatrachidae) with description of twelve new species". Zootaxa. 3029 (1): 49–52. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3029.1.1. ISSN 1175-5334.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2023). "Nyctibatrachus". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. American Museum of Natural History. doi:10.5531/db.vz.0001.

- Annandale, N. (21 August 1910). "Description of a South Indian frog allied to Rana corrugata of Ceylon". Records of the Zoological Survey of India. 5 (3): 191. doi:10.26515/rzsi/v5/i3/1910/163741. ISSN 2581-8686. S2CID 251650759.

- Garg, Sonali; Suyesh, Robin; Sukesan, Sandeep; Biju, S. D. (21 February 2017). "Seven new species of night frogs (Anura, Nyctibatrachidae) from the Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot of India, with remarkably high diversity of diminutive forms". PeerJ. 5: e3007. doi:10.7717/peerj.3007. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5322763. PMID 28243532.

- Krutha, Keerthi; Dahanukar, Neelesh; Molur, Sanjay (26 December 2017). "Nyctibatrachus mewasinghi, a new species of night frog (Amphibia: Nyctibatrachidae) from Western Ghats of Kerala, India". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 9 (12): 10988. doi:10.11609/jott.2413.9.12.10985-10997. ISSN 0974-7907.

- Gururaja, Kotambylu Vasudeva; Dinesh, K. P.; Priti, H.; Ravikanth, G. (16 May 2014). "Mud-packing frog: A novel breeding behaviour and parental care in a stream dwelling new species of Nyctibatrachus (Amphibia, Anura, Nyctibatrachidae)". Zootaxa. 3796 (1): 41. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3796.1.2. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 24870664.

- Meenakshi, K.; Remya, Reveendran; Sanil, George (15 February 2010). "DNA barcoding and microsatellite marker development for Nyctibatrachus major: The threatened amphibian species". Proceedings of the International Symposium on Biocomputing. ACM. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1145/1722024.1722029. ISBN 978-1-60558-722-6. S2CID 35880867.

- Krishnamurthy, S. V.; Katre, Shakuntala; Reddy, S. Ravichandra (1992). "Structure of femoral gland and habitat features of an endemic anuran, Nyctibatrachus major (Boulenger)". Journal of the Indian Institute of Science. 72: 385–393.

- Daniels, R. J. Ranjit (2005). Amphibians of Peninsular India. Hyderabad: Universities Press. pp. 226–228. ISBN 9788173715143. OCLC 475620800.

- Kuramoto, Mitsuru; Joshy, S. Hareesh (2001). "Advertisement call structures of frogs from Southwestern India, with some ecological and taxonomic notes". Current Herpetology. 20 (2): 90. doi:10.5358/hsj.20.85.

- Sreekumar, S.; Dinesh, K. P. (2020). "Amphibians of agro-climatic zones of Maharashtra with updated checklist for the state". Records of the Zoological Survey of India. 120: 38. doi:10.26515/rzsi/v120/i1/2020/131811 (inactive 25 August 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Gururaja, K. V.; Manjunatha Reddy, A. H.; Keshavayya, J.; Krishnamurthy, S. V. (2003). "Habitat occupancy and influence of abiotic factors on the occurrence of Nyctibatrachus major (Boulenger) in Central Western Ghats, India". Russian Journal of Herpetology. 10 (2): 90–91.

- Girish, Kalamanji Govindaiah; Bhatta Krishnam, Sannanegunda Venkatarama (28 December 2009). "Distribution of tadpoles of large wrinkled frog Nyctibatrachus major in central Western Ghats: influence of habitat variables". Acta Herpetologica. 4 (2): 157–158. doi:10.13128/ACTA_HERPETOL-3417.

- Krishnamurthy, S. V.; Gururaja, K. V.; Reddy, A. H. M. (2001). "Nyctibatrachus major (Large Wrinkled Frog), Feeding Habit". Herpetological Review. 32 (3): 182.

- Kuramoto, Mitsuru; Joshy, S. Hareesh (2000). "Sperm morphology of some Indian frogs as revealed by SEM". Current Herpetology. 19 (2): 66. doi:10.5358/hsj.19.63. ISSN 1881-1019. S2CID 82682100.

- Krishnamurthy, S. V.; Das, Meenakumari; Gurushankara, H. P.; Vasudev, Venkateshaiah (2008). "Nitrate-induced morphological anomalies in the tadpoles of Nyctibatrachus major and Fejervarya limnocharis (Anura: Ranidae)". Turkish Journal of Zoology. 32 (3): 242–243.

- Krishnamurthy, S. V.; Das, Meenakumari; Gurushankara, H. P.; Griffiths, R. A. (2006). "Effects of nitrate on feeding and resting of tadpoles of Nyctibatrachus major (Anura: Ranidae)". Australasian Journal of Ecotoxicology. 12: 123, 125–126.