Malcolm Delevingne

Sir Malcolm Delevingne, KCB, KCVO (11 October 1868 – 30 November 1950) was a British civil servant who worked in the British Home Office from 1892 through his retirement in 1932. He was a significant influence on safety regulations in factories and mines, and was an original member of the League of Nations' Opium Advisory Committee.[1]

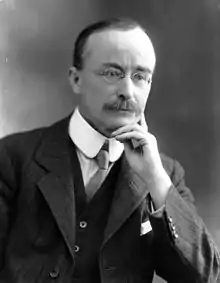

Sir Malcolm Delevingne | |

|---|---|

Delevingne in 1920 | |

| Born | 11 October 1868 Westminster, London |

| Died | 30 November 1950 (aged 82) West Kensington, London |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Civil Servant |

Family and education

Malcolm Delevingne was born in London, the second child of Ernest Thomas Shaw Delevingne and wife Hannah Gresswell. His father, a wine and liquor merchant, was born in Paris to British parents of French Huguenot descent.[2] His elder brother, Edgar, was a teacher at the City of London School for 40 years, while his younger brother, Walter, had his own distinguished career in the Indian Civil Service.[2]

Malcolm was raised in the comfortable suburb of Ealing and was educated at the City of London School from 1877 and 1887. He read classics at Trinity College, Oxford, taking first-class honours in classical moderations in 1889 and in Literae Humaniores in 1891.[1] He had strong religious convictions, privately held, which informed his public stance on worker's safety, narcotics and child welfare.[2]

Career

In 1892, at the age of 24, Delevingne passed the civil service exam for clerkships and took his first job at the Local Government Board. After a brief period, he transferred to the British Home Office.[2] From 1894 to 1896, he served as Private Secretary to Home Secretary Sir Matthew Ridley, and continued to rise through the ranks of the Home Office.[1]

In 1922, he was promoted to Deputy Permanent Under Secretary of State, a position he held until his retirement in 1932.[3][4]

Worker safety

Though Delevingne was involved with many aspects of the Home Office, he was particularly concerned with occupational health and safety, with special focus on regulations for factories and coalmines. He was instrumental in the passage of the Police, Factories, etc. (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act of 1916, which required workplaces to provide first aid, washrooms, drinking water and other amenities. He did a considerable amount of work on the Coal Mines Act, 1911,[2] which required all mine owners to establish rescue stations, provide teams of trained rescuers, and to keep and maintain rescue apparatus on site.[5]

While heading the Factory Department at the Home Office, he was one of the principal movers behind the establishment of the International Labour Office and initially served on its Governing body. He was also influential in reorganised the Factory Department and establishing an industrial museum, the Home Office Industrial Museum, to promote worker safety, health and welfare.[2] Delevingne was sent as part of the British delegation to international labour conferences in Bern in 1905, 1906 and 1913, in Washington, D.C. in 1919, and in Geneva in 1923, 1928 and 1929. British delegate to the Labour Commission of the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.[1]

Delevingne became an expert on factories, and contributed a lengthy article to The Times in July 1933, to coincide with the centenary of the establishment of the Factory Inspectorate.[6] In his 1950 obituary, The Times wrote that Delevigne was "undoubtedly an unobtrusive, but powerful, force behind much of the factory legislation that was passed during the first quarter of the present century. This was a subject that he knew from end to end, not only on its practical but also on its historical side."[1]

After his retirement, he stayed active in the government's role in industrial safety. He served as chairman of a committee on work shifts for women and youth in 1933, on a commission of safety in coal mines in 1936, chairman of a committee on rehabilitation of the injured, and as chairman of the Safety in Mines Research Board from 1939 to 1947.[2]

Drug control

Delevingne was an expert on the control of narcotic drugs. He believed that the key to narcotics control lay in curbing their supply and that the drug trade was "a great evil which must be fought."[2] He convinced his colleagues that growers and manufacturers must be forced to cut back production to designated levels. He never gave up on promoting narcotics controls even after the International Opium Convention of 1925. He convinced the League of Nations to intervene in three conferences (1925: Certificate system- the exporter could only sell to a legitimate importer. This was intended to dry up the flow into the market; 1931: Limited production of manufactured drugs, illicit factories then began; 1936: Law enforcement issue, this involved the extradition of drug smugglers and co-operation between countries.) Delevingne continued to promote the prosecution of illicit drug businesses.

As one of the Undersecretaries of State at the Home Office, Delevingne represented the United Kingdom's interests on the League of Nations' Opium Committee from 1931.[1]

He also stayed active in this area after his retirement, representing the United Kingdom at international opium conferences until 1947.[2]

Barnardo's

Delevingne became actively involved in the children's foundation Barnardo's in 1903, joining its governing body in 1934, subsequent to his retirement.

Honours

In recognition of his services, Delevingne was appointed a Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath in the 1911 Coronation Honours,[7] a Knight Commander of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath in 1919, and a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order in 1932.

References

- "Obituary: Sir M. Delevingne". The Times. 1 December 1950. p. 8.

- Bartrip, P. W. J. (2004). "Delevingne, Sir Malcolm (1868–1950), civil servant". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3277. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Martindale pp. 31–39

- "Sir Malcolm Delevingne – Retirement From Post at the Home Office". The Times. 1 November 1932. p. 14.

- "Mines Rescue" (PDF). National Coal Mining Museum for England. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "Civilizing The Factory – The Creation of Inspectors: A Century's Gains". The Times. 20 July 1933. p. 13.

- "No. 28505". The London Gazette (Supplement). 19 June 1911. p. 4593.

Sources

- South, Nigel (1998). "ch. 6". In Coomber, Ross (ed.). The Control of Drugs and Drug Users: Reason Or Reaction?. CRC Press. ISBN 90-5702-188-9.

- Martindale, Hilda (1970). "Section 3". Some Victorian Portraits and Others. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8369-8030-1.

- Goto-Shibata, Harumi (October 2002). "pp. 969-991". The International Opium Conference of 1924-25 and Japan. pp. 969–991. doi:10.1017/S0026749X02004079. JSTOR 3876480. S2CID 144258209.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)

- Meyer, Kathryn (2002). "pp. 16-34". Webs of Smoke: Smugglers, Warlords and the History of the International Drug Trade. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-2003-5.