Malouma

Malouma Mint El Meidah (Arabic: المعلومة منت الميداح, romanized: al-Maʿlūma Mint al-Maydāḥ), also simply Maalouma or Malouma ( /mɑːloʊmɑː/; born October 1, 1960), is a Mauritanian singer, songwriter and politician. Raised in the south-west of the country by parents versed in traditional Mauritanian music, she first performed when she was twelve, soon featuring in solo concerts. Her first song "Habibi Habeytou" harshly criticized the way in which women were treated by their husbands. Though an immediate success, it caused an outcry from the traditional ruling classes. After being forced into marriage while still a teenager, Malouma had to give up singing until 1986. She developed her own style combining traditional music with blues, jazz, and electro. Appearing on television with songs addressing highly controversial topics such as conjugal life, poverty and inequality, she was censored in Mauritania in the early 1990s but began to perform abroad by the end of the decade. After the ban was finally lifted, she relaunched her singing and recording career, gaining popularity, particularly among the younger generation. Her fourth album, Knou (2014), includes lyrics expressing her views on human rights and women's place in society.

Malouma | |

|---|---|

| المعلومة منت الميداح | |

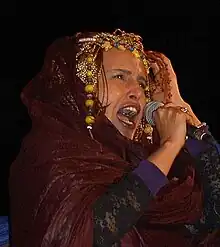

Malouma in concert, 2004 | |

| Born | Malouma Mint El Meidah October 1, 1960 |

| Nationality | Mauritanian |

| Other names | Malouma Mint Mokhtar Ould Meïddah Malouma Mint Elmeida Mint El Meydah Malouma Bint al-Meedah |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, songwriter and politician |

Alongside her singing, Malouma has also fought to safeguard her country's music, urging the government to create a music school, forming her own foundation in support of musical heritage, and in 2014 creating her own music festival. She was elected a senator in 2007, the first politician in her caste, but was arrested the following year after a coup d'état. When elections were again held in 2009, she became a senator for the opposition Ech-Choura party where she was given special responsibilities for the environment. This led in 2011 to her appointment as the IUCN's Goodwill Ambassador for Central and West Africa. In December 2014, she announced she was moving from the opposition to join the ruling party, the Union for the Republic, where she felt she could be more effective in contributing to the country's progress. Her work has been recognized by the French, who decorated her as a Knight of the Legion of Honor, and the Americans, whose ambassador to Mauritania named her a Mauritanian Woman of Courage.

Early life

Malouma Mint Moktar Ould Meidah was born in Mederdra in the Trarza Region of south-western Mauritania, on October 1, 1960,[1] the year the country gained independence from France.[2] Born into a griot family,[3] she grew up in the small desert village of Charatt, just south of Mederdra in West Africa.[4] Her father, Mokhtar Ould Meidah, was a celebrated singer, tidinet player and poet[3] while her grandfather, Mohamed Yahya Ould Boubane, is remembered as a talented writer and tidinet virtuoso.[5] Her mother also came from a family of well-known traditional singers.[6] She taught her daughter to play the ardin, a ten-stringed harp traditionally played by women, when she was six.[7][8]

"Here, artists traditionally praise the ruling tribes and emirs. When I wanted to devise a new kind of music suitable for a modern Mauritania, I thought about changing the lyrics. In my texts, I am committed to educating people".

—Malouma, quoted in RFI Musique in 2003.[9]

Malouma commenced her education at elementary school in 1965 in Mederdra. She qualified as an elementary school teacher in 1974 in Rosso. According to the traditions of her country, those of the Meidah family are required to carry on the art of their ancestors. As a result, she had to give up her aspirations to teach.[10] Members of each caste are allowed only to marry other members of society within the same caste and the entire society is divided by castes politically, economically, and culturally. Movement outside of a particular caste is forbidden.[6] She learned to play the traditional stringed instruments only women play, especially the ardin harp, and was taught traditional Mauritanian music by her father, who enjoyed an eclectic mix of music.[10] As a result, she grew up listening to classical western works such as Beethoven, Chopin, Mozart,[11] Vivaldi[2] and Wagner, as well as the music of traditional Berber, Egyptian, Lebanese and Senegalese artists. She often accompanied her parents who sang traditional griots.[11]

Malouma began singing as a child, first performed on the stage when she was twelve and began appearing in solo concerts with a traditional repertoire by age fifteen.[4] In addition to her father's guidance, she was inspired by other traditional artists including Oum Kalthoum, Abdel Halim Hafez, Fairouz, Dimi and Sabah. As she matured, she increasingly became interested in blues music, which appealed to her as it bore a resemblance to the traditional music she knew.[5] Malouma wrote her first song, "Habibi Habeytou" (My beloved, I loved him) when she was sixteen.[3] It was a song protesting the tradition of men turning their wives out of their homes to marry younger women. It brought her instant recognition, but created a backlash, causing physical attacks from the established Muslim community.[12] Soon after she wrote it, her family moved to Nouakchott, the capital, to help her launch her music career,[12] but in the strongly traditional society, Malouma was forced to marry, abandoning singing until the late 1980s.[4] She was later accused by her father of ruining his reputation. In addition to the criticisms stemming from her songs, she had disgraced her family by divorcing twice: her first husband had been forced upon her, while the second came from a noble family, who would not allow her to sing. Yet after hearing one of her songs, her father commented: "You have created something new and I find it touching. Unfortunately, I will not live long enough to be able to protect you."[13]

Music career

Background

Malouma's first major appearance was in 1986, when she revealed her fusion style, combining traditional interpretations with more modern developments including blues, jazz, and electro.[2] Her early songs "Habibi habeytou", "Cyam ezzaman tijri" and "Awdhu billah", which openly addressed love, conjugal life and the inequalities between men and women, contrasted strongly with what was considered acceptable in her home country. Nevertheless, they had strong popular appeal, especially for young women. Malouma carefully developed her approach, blending traditional themes with the rich repertoire and instrumentation of modern popular music.[5] Typically, her compositions are based on the traditions of classical Arab poets, such as Al-Mutanabbi and Antarah ibn Shaddad, whose verses cover political criticism, personal sacrifice and support for the weak and oppressed.[14] She has also drawn on traditional Mauritanian themes, modernizing both the lyrics and musical presentation.[15]

From the beginning, Malouma sang in a variety of languages, including traditional Arabic, Hassania (Mauritanian Arabic), French and Wolof.[16] By singing in various languages, she sought to air her message to a broader audience.[3] It was not long before she appeared on television together with her sister, Emienh, and her brother, Arafat, an instrumentalist. Their style was controversial, especially after the release of her song "Habibi Habeytou" and a 1988 appearance at the Carthage Festival in Tunis, as she addressed social issues, such as poverty, inequality and disease which were not generally acceptable in Mauritania.[10] Her participation in the Carthage event led to her subsequent appearance on Arab satellite channels, giving her greater exposure.[17] Malouma became nationally known and was a sought after performer until a 1991 song about freedom of speech.[18] After being censored for writing songs promoting women's rights,[19] she was banned from appearing on public television and radio, holding concerts, and was even denied a permanent address.[18] She did not perform anywhere for a lengthy period[18] but in the late 1990s she began to sing in other African countries,[20] in Europe,[9] and in the United States.[21] While she won audiences among the people, Malouma was persecuted by both the moral authorities and authoritarian governments, her music being completely banned until 2003 when a crowd of 10,000 people successfully called on President Ould Taya to cancel her censorship.[8][22] Some restrictions remained until the overthrow of the President Ould Taya's regime in 2005.[11]

The traditional griots are songs of praise, but Malouma used her voice to speak out against child marriages, racial and ethnic discrimination, slavery and other divisive issues facing a country at the crossroads of the Arab world and Africa.[2] She also sang about illiteracy, HIV/AIDS awareness and in support of children's vaccinations.[3]

Albums and bands

Malouma's first album, Desert of Eden was released by Shanachie Records in 1998. When it was produced, she felt that the traditional elements were taken out during production, resulting in "bland electronic pop",[23] though it received good reviews from JazzTimes.[24] In the early 2000s, she began working with a group called the Sahel Hawl Blues made up of ten young Mauritian musicians of different ethnic origins (Moor, Fula, Toucouleur, Sonike, Wolof and Haratin), demonstrating her desire to overcome racial differences. In so doing, she was also able to extend music based on the traditional string instruments of the Moors to include the beat of the djembe, the darbouka, and the bendir frame drum. Led by Hadradmy Ould Meidah, the group supported her desire to modernize traditional music, making it more accessible to the wider world.[22][25] They toured with her in 2004 and 2005[20] and worked with her on her second album, Dunya (Life), which sought to reclaim her musical heritage. Produced by Marabi Records in 2003, the album contained twelve songs which blended harps, lutes and skin drums with electric guitar and bass, and traditional genres like serbat, which usually focuses on a single minor chord, with jazz.[23]

Malouma's album, Nour (Light), was released in France on March 8, 2007 in celebration of International Women's Day.[26] Produced by Marabi/Harmonia Mundi, it featured a broad mix of music from lullabies to dance music. Malouma's singing was supported by a group of fifteen studio musicians on a variety of electronic and traditional instruments.[11] Reviews were mixed,[27][28] but the CD ranked as number 14 on the World Music Charts Europe by September 2007.[29] After a hiatus from music to focus on politics, Malouma relaunched her musical career on October 5, 2014. Dressed in a blue toga, she presented her new album, Knou, at a special event, appearing on stage for the first time since her election seven years earlier.[13][30] She chose to call it "Knou", which is the name of a dance usually performed by women in western Mauritania.[31] The album focused on traditional dancing melodies,[10] but bridged generations by adding modern twists. Weaving jazz, rock and reggae rhythms, into the traditional songs, it was well received.[32]

Music festivals

Music festival appearances have been a large part of Malouma's career. The first time she participated in an international festival was in Carthage, Tunisia in 1988; her performance proved to be highly successful.[8] Malouma returned to the stage in August 2003, appearing at the Festival des Musiques Métisses in Angoulême, France, combining traditional Moorish music with a more modern approach in numbers from her album Dunya. She was not only selected as "artiste de l'année" (artist of the year) but was nicknamed "Diva des Sables" (Diva of the Sands).[8] Her success continued in October of the same year at the World Music Expo in Seville, Spain, where she was selected by the jury as a featured performer.[33][34] One of the highlights of Angoulême's Festival des Musiques Métisses was her nostalgic rendering of "Mreïmida". The song proved equally popular in Mauritania at the 2004 Nouakchott Festival of Nomadic Music. She was finally permitted to take part after her ban had been lifted. She appeared there with another female Mauritanian star, Dimi Mint Abba, and was accompanied by the French pianist Jean-Philippe Rykiel on a synthesizer.[8]

Malouma toured in the United States in 2005 with appearances in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Chicago, Illinois, Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, Lafayette, Louisiana (for the Festival International de Louisiane), before finishing in New York City.[35] Two years later, Malouma participated in the 32nd Paléo Festival in Nyon, Switzerland, which focused on musicians from North Africa.[36] She also appeared in the 2010 edition of the Førde International Folk Music Festival, held in Førde, Norway under the theme of "freedom and oppression".[37][38] At the 2012 Festival International des Arts de l’Ahaggar in Abalessa, Algeria, she was chosen as one of the three artists to perform in the grand finale, receiving acclaim for the balance of instrumentals and vocals, the composition, and her two back-up vocalists.[39] Her 2013 performance at the World of Music, Arts and Dance Festival (WOMAD), held in Wiltshire, England included a "Taste The World" event where performers not only sang, but prepared a dish from their country. Malouma's lamb-filled pancakes[40] were a highlight of the festival presenting an up-front and personal encounter with the musician for the audience. Her second stage appearance at the event also brought praise for her rock-star performance embracing modern music.[41] In 2014, Malouma participated in the Meeting of the Arts of the Arab World, a festival in Montpellier, France,[42] as well as at the Parisian Festival Rhizomes.[43]

In June 2022, Malouma performed in Nouakchott in the first the international musical gala in the country after the Covid-19 pandemic next to the Spanish guitarist Rafael Serrallet.[44]

Politics

Malouma, officially Malouma Meidah, first became politically active as a member of the opposition party in 1992, speaking out in favor of democratization.[2] In 2007, in what was widely considered the first freely held and fair election in the country,[45] she was elected to the Senate of Mauritania,[10] as one of the six women senators in a legislature of 56 members.[46] She was the first person from the musician iggawen caste to serve in politics.[6] Shortly after she was elected, a coup d'état took place in Mauritania in 2008 and deposed the first democratically elected head of state, Sidi Mohamed Ould Cheikh Abdallahi.[2] Because she had written songs criticizing the coup, Malouma was arrested and over a thousand cassettes and CDs of her recordings were seized.[47] After the coup, the leader, Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, allowed elections to proceed with only minor delays. He was elected president in July 2009 and the Senate elections in which one-third of the members faced re-election also were held.[48] The parliamentary opposition group, called "Ech-Choura", of which Malouma was a member and served as the First Secretary,[49] constituted 12 members of the 56-member Senate after the 2009 election.[48] She also served on the Parliamentary Group for the Environment[50] and as 2nd Secretary of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Armed Forces.[51]

Malouma announced in April 2014 that she no longer felt she could keep up her political fight for democracy, although she would continue to support cultural and environmental causes.[13] Even so, her Knou lyrics included allusions to her favorite political causes: equality and rights for all, women's place in society, and education for the young, all under threat, as well as environmental protection. Referring to her political role as a senator for the opposition party Assembly of Democratic Forces, in August 2014 she commented: "I use my presence and speaking time in the chamber to extend the effect of my texts and my songs. Whenever I run into ministers or important personalities, I tell them what the people expect of them."[31] She has also continued to speak out about issues such as Palestine and the Iraqi War in her songs.[10] At a press conference on December 16, 2014, Malouma announced she was leaving the opposition and joining the ruling party, the Union for the Republic, on the grounds that she could participate more effectively in building Mauritania by standing behind the policies of the current leader Aziz.[10]

Environment and culture

In addition to her work in her music career and political activism, Malouma is involved in both environmental protection and cultural preservation projects.[13]

Environmental activism

Malouma Mediah was involved in a project in 2009, to relocate 9,000 slum-dwelling families from the outskirts of the city into inner city neighborhoods. She insisted that for health reasons, improvements would first have to be made to the infrastructure.[52] In August 2011, the International Union for Conservation of Nature appointed Malouma as Goodwill Ambassador for Central and West Africa. The position required her to raise awareness of environmental problems with a view to introducing sustainable solutions. On her appointment she commented: "I am delighted at the confidence that IUCN just placed in me. I am deeply honored. I will do my best to fulfill this great responsibility."[53][54] In September 2012, she performed in a concert given during the 2012 IUCN World Conservation Congress held on Jeju Island, South Korea.[55]

Cultural preservation

As a result of the Mauritanian caste system, the development of traditional music in Mauritania has been supported by just a few families, threatened by a closed culture in which there are limited opportunities for support. As families have no means of preserving their music, or recording it, their creations are often forgotten owing to the absence of family members interested in ensuring their survival. The situation has been compounded by rules forbidding their support from outside the family environment.[56] Concerned that the musical traditions of the country were vanishing,[57] in 2006, Malouma urged the government to create a school to preserve the country's music heritage, even introducing a measure to Parliament.[6] In 2011, she created the Malouma Foundation in support of the preservation of the national musical heritage.[32] The foundation aims to protect and preserve the Arab, African, and Berber roots of music in Mauritania and, to that end, is collecting and storing music from throughout the country to both preserve it and make it available for other uses, including education.[58] Long concerned that the Moorish music traditions of her country were being replaced by the Malian and Moroccan music preferred by younger people,[12] in 2014, she created a Mauritanian Music Festival.[13]

When she produced Nour in 2007, Malouma collaborated with the painter, Sidi Yahia, hoping to create visual images to illustrate the songs in the album. Eleven paintings resulted from the joint venture[32] and Malouma and Yahia presented cultural discussions about their works titled "Regarder la musique, écouter la peinture?" (Watch the music, listen to the painting?) In 2013 a month-long exhibit was presented to showcase the paintings and the music which inspired them at a gallery in Nouakchott.[59] In 2015, after receiving a grant from the Arab Culture Fund, Malouma convinced musicians to collaborate with artists when recording their music. The project aimed at collecting music from six artists and producing an album of their works. Malouma has continued to press for the establishment of a music school, though it would require overcoming taboos on family restrictions in regard to musical legacy.[57]

Awards and recognition

Malouma was selected in 2003 by the jury as one of the World Music Expo (WOMEX) showcase artists[33] and two years later she was selected by BBC musicologist Charlie Gillett, for his 2005 selected compilation Favorite Sounds of the World CD.[33][60] That same year, N'Diaye Cheikh, a Mauritanian filmmaker, produced a documentary about her, entitled Malouma, diva des sables (Malouma, Diva of the Sands) with Mosaic Films, which won Best Documentary at the Festival international du film de quartier (FIFQ; Dakar, Senegal)[61] and a 2007 Prize of Distinction from Festival International de Programmes Audiovisuels (FIPA), held in Biarritz, France.[62] She was a runner-up for the Middle East and North Africa in the 2008 BBC Radio 3 Awards for World Music.[63] The griot-artist community of Mauritania has also acclaimed her by calling her the "first true composer in Mauritania".[20]

Malouma was decorated in 2013 as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French ambassador, Hervé Besancenot, acting on behalf of President Nicolas Sarkozy of France.[10][64] On January 20, 2015, Malouma, Mauritania's "singer of the people and Senator", was honored by the American ambassador, Larry André, at a lunch attended by notable leaders, especially women, from the country's civil society. Presenting Malouma with the Mauritanian Woman of Courage award, the ambassador noted her "exceptional courage and leadership in advocating human rights, women, gender equality and harmony amongst the cultural traditions of Mauritania".[65]

Selected works

- 1998, Desert of Eden (album), a mix of West-African and Arabic-Berber sounds, released in the West[66]

- 2003, Dunya (Life), 12-track album, recorded on the Marabi label in Nouakchott; a mix of blues, rock, and traditional melodies from southern Mauritanian and Indo-Pakistani, all sung in Hassaniya Arabic[8][9]

- 2007, Nour (Light), 12-track album, recorded on the Marabi label during her stay in Angloulême in 2003 with the support of festival organizer Christian Mousset; a collection of dance beats featuring electric guitars but without the traditional instruments of the Moors[8][11]

- 2008, Malouma received accolades for her blues song "Yarab" on the album Desert Blues 3—Entre Dunes Et Savanes released by Network Medien[67]

- 2009, Malouma was a featured composer and vocalist on two songs, "Missy Nouakchott"[68] and "Sable Émouvant"[69] on the 2009 Ping Kong album by DuOud[70]

- 2014, Knou (album), a collection of ethno-pop tunes woven through with traditional tidinit lute and ardin harp instruments[71]

See also

References

Citations

- "Malouma: Biographie" (in French). France Inter. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- Châtelot 2009.

- African Business 2003, p. 66.

- Rush, et al. 2004–2005, p. 10.

- Omer.

- الخليل (Khalil) 2008.

- Lusk 2008.

- Taine-Cheikh 2012.

- Elbadawi 2003.

- Al Jazeera Encyclopedia 2014.

- De la Haye 2007.

- Skelton 2007.

- Berthod 2014.

- Rush, et al. 2004–2005, pp. 31, 33–34.

- Rush, et al. 2004–2005, p. 31.

- Rush, et al. 2004–2005, p. 8.

- Folkeson 2008.

- Rush, et al. 2004–2005, p. 12.

- Didcock 1998.

- Rush, et al. 2004–2005, p. 11.

- Rush, et al. 2004–2005, p. 7.

- Seck 2007.

- Eyre 2005.

- Woodard 1998, p. 93.

- Mousset 2008.

- Labesse 2007, p. 30.

- Denselow 2007.

- Orr 2007.

- World Music Central 2007.

- WikiTV 2014.

- Diallo 2014.

- Lemancel 2014.

- Romero 2003.

- Mondomix 2003.

- Romero 2005.

- Paléo Festival 2007.

- World Music Central 2010.

- Landssamanslutninga av nynorskkommunar 2010.

- Presse-Algerie 2012.

- Johnson 2013.

- Elobeid 2013.

- CRIDEM Communication 2014.

- Degeorges 2014.

- ELDIAdigital.es. "Rafael Serrallet lleva su guitarra por el desierto mauritano". eldiadigital.es Periódico de Castilla-La Mancha (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- Freedom House 2009.

- Tran 2007.

- U.S. Department of State 2012, p. 427.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union 2011.

- Sénat Mauritanien 2009a.

- Sénat Mauritanien 2009b.

- Sénat Mauritanien 2009c.

- Integrated Regional Information Networks 2009.

- Smith-Asante 2011.

- Schulman 2015, p. 6.

- IUCN 2012.

- Bucher & Outpost 2015, p. 1.

- Bucher & Outpost 2015, p. 2.

- Bensignor 2014.

- ZeinArt 2013.

- World Music Central 2005.

- AfriCine 2013.

- Africa Doc Network 2007.

- BBC 2008.

- Mamady 2013.

- U.S. Department of State 2015.

- Hammond 2004, p. 159.

- Nelson 2008.

- Missy Nouakchott.

- Sable Émouvant.

- Library of Congress.

- Labesse 2014.

Sources

- Bensignor, François (April 24, 2014). "Malouma: le retour d'une chanteuse sénatrice". Mondomix (in French). Paris, France. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Berthod, Anne (April 28, 2014). "Malouma, la diva contestataire de Nouakchott". Télérama (in French). Paris, France. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Bucher, Nathalie Rosa (March 23, 2015). Saving Mauritania's Musical Heritage (PDF). The Outpost (Report). Beirut, Lebanon: Arab Culture Fund. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- Mousset, Christian (2008). "Malouma". Conseil francophone de la chanson (in French). Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Châtelot, Christophe (July 14, 2009). "Malouma, diva rebelle". Le MondeAfrique (in French). Paris, France. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Degeorges, Françoise (June 25, 2014). "Le festival Rhizomes + rencontre avec la chanteuse mauritanienne Malouma". France Musique (in French). Paris, France. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- De la Haye, Fleur (March 16, 2007). "Malouma La griotte mauritanienne sort Nour". RFI Musique (in French). Paris, France. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Denselow, Robin (May 4, 2007). "CD Malouma, Nour". The Guardian. London, England. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Diallo, Bios (August 8, 2014). "Musique maestro: Malouma, une diva citoyenne". Cridem (in French). Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- Didcock, Barry (November 27, 1998). "No Matter How Hard the Censors Try, You Just Can't Keep a Good Song Down". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016 – via HighBeam Research.

- Elbadawi, Soeuf (June 10, 2003). "Musiques métisses 2003 Angoulême, fidèle à sa légende" (in French). Paris, France: RFI Musique. Archived from the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Elobeid, Fadil (July 31, 2013). "Review: Womad 2013". Whats on Africa. London, England: Royal African Society. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Eyre, Banning (April 14, 2005). "Desert storm: Malouma brings the blues from Mauritania". The Boston Phoenix. Boston, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on October 10, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Folkeson, Annika (September 15, 2008). "First She Took Azm Palace, Then She'll Take the Golan". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on October 25, 2023 – via TheFreeLibrary.

- Hammond, Andrew (2004). Pop Culture in the Arab World!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851094493. Archived from the original on October 25, 2023. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- Johnson, Steven (August 2, 2013). "Festival Review: WOMAD 2013". Music OMH. Archived from the original on January 16, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- الخليل, أحمد (September 24, 2008). "أول مغنية عربية تصل إلى البرلمان.. معلومة بنت الميداح نقلت الفن الموريتاني إلى العالمية". Tishreen News (in Arabic). Damascus, Syria. Archived from the original on January 16, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Labesse, Patrick (March 13, 2007). "Les femmes dopent les musiques du monde". Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on October 25, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2016 – via EBSCO.

- Labesse, Patrick (May 20, 2014). "Malouma tisse sons pop et musique mauritanienne". Le Monde (in French). Paris, France. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Lemancel, Anne-Laure (April 11, 2014). "Malouma, chanter ses combats Nouvel album, Knou". RFI Musique (in French). Paris, France. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Lusk, Jon (2008). "Malouma (Mauritania)". BBC – Awards for World Music. BBC. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Mamady, Camara (May 25, 2013). "Malouma Mint Meidah, la "Chanteuse du Peuple" Médaillée de L'ordre de la Légion d'honneur". Acturim Overblog, Le Rénovateur Quotidien (in French). Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Nelson, TJ (November 28, 2008). "Bending the Blues". Durham, North Carolina: World Music Central. Archived from the original on February 15, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- Omer, Ould. "Malouma". Africultures (in French). Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Orr, Tom (July 8, 2007). "Not Just Maur of the Same". World Music Central. Durham, North Carolina. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- Romero, Angel (August 5, 2003). "WOMEX 2003 Showcase Selection Announced". World Music Central. Durham, North Carolina. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- Romero, Angel (March 25, 2005). "Mauritania's Malouma Presents Free African Rhythms & Arabic Lyrics Workshop in Boston". World Music Central. Durham, North Carolina. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Rush, Omari; Lin, Michelle; Nelson, Erika; Baker, Rowyn; Johnson, Ben (2004–2005). "Malouma and the Sahel Hawl Blues: Teacher Resource Guide" (PDF). UMS Youth Education. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Musical Society, University of Michigan. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Schulman, Mark (2015). 2014 IUCN annual report. IUCN. ISBN 978-2-8317-1725-8.

- Seck, Nago (May 7, 2007). "Malouma Mint El Meidah" (in French). Aubervilliers, France: Afrisson. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- Skelton, Rose (April 30, 2007). "Mauritania's fiery singing senator". London, England: BBC. Archived from the original on December 25, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Smith-Asante, Edmund (August 11, 2011). "IUCN appoints Maalouma Mint Moktar Ould Meidah as Goodwill Ambassador". Ghana Business News. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Taine-Cheikh, Catherine (2012). "Les chansons de Malouma, entre tradition, world music et engagement politique". Quaderni di Semistica (in French). Florence, Italy: Dipartimento de Linguistica, Università di Firenze. 28: 337–362. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Tran, Phuong (August 7, 2007). "Mauritanian Singer Tackles Social Problems in Legislature". New York City, New York: Voice of America. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Woodard, Josef (May 1998). "Spheres". Jazz Times. Silver Spring, Maryland: JazzTimes, Inc. ISSN 0272-572X.

- "Singer of the People". African Business. No. 291. October 2003. ISSN 0141-3929. Archived from the original on October 25, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2016 – via EBSCO.

- "Malouma, diva des sables". Africa Doc Network. 2007. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "N'diaye Cheikh". AfriCine. 2013. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "المعلومة بنت الميداح.. ألحان الفن وأحلام السياسة". Al Jazeera (in Arabic). Doha, Qatar: Al Jazeera Encyclopedia. February 12, 2014. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- "Missy Nouakchott". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- "Sable Émouvant". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- "BBC Radio 3: Awards World Music '08". BBC. 2008. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Festival Arabesques: Malouma, la grande dame d'Arabesques" (in French). Nouakchott, Mauritania: Carrefour de la République Islamique de Mauritanie Communication. May 20, 2014. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Mauritania:Freedom in the World 2009". Washington, D.C.: Freedom House. 2009. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- "Mauritania: City versus slum". Integrated Regional Information Networks. March 31, 2009. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- "Mauritania: Majlis Al-Chouyoukh (Senate)" (in French). Le Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland: Inter-Parliamentary Union. 2011. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- "Highlights: World Conservation Congress, Jeju 2012" (PDF). IUCN. September 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- "Fridom og undertrykking i Førde" (in Norwegian). Oslo, Norway: Landssamanslutninga av nynorskkommunar. July 5, 2010. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Library of Congress. "DuOud (Musical group) prf". Washington, DC: Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 25, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- "Atmosphere". Seville, Spain: Mondomix. October 24, 2003. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "2007 Paléo Festival Nyon". Nyon, Switzerland: Paléo Festival Nyon. 2007. Archived from the original on February 15, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Malouma, Bambino et Tinariwen pour un final en apothéose" (in French). Algiers, Algieria: Presse-Algerie. February 20, 2012. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Groupe Ech-choura" (in French). Nouakchott, Mauritania: Sénat Mauritanien. 2009. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- "Groupe parlementaire pour l'environnement" (in French). Nouakchott, Mauritania: Sénat Mauritanien. 2009. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- "Commission des Affaires étrangères, de la défense et des Forces Armées" (in French). Nouakchott, Mauritania: Sénat Mauritanien. 2009. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- U.S. Department of State (2012). Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2009. Vol. I: Africa, East Asia and the Pacific. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. GGKEY:EXCA0EGBR49.

- "Press Release on the 2015 Mauritanian Woman of Courage Award". U.S. Department of State. January 20, 2015. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- "Malouma Mint Meidah présente "Knou", son troisième album" (in French). WikiTV (YouTube). October 6, 2014. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- "Charlie Gillett Introduces His Favorite Sounds of the World on 2 CDs". Durham, North Carolina: World Music Central. October 17, 2005. Archived from the original on February 15, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- "WOMEX Announces Top 15 World Music CDs of the Year". Durham, North Carolina: World Music Central. September 7, 2007. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- "Interview with Mauritanian Griot Malouma". Durham, North Carolina: World Music Central. July 7, 2010. Archived from the original on February 15, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Malouma mint Meidah et Sidi Yahya". ZeinArt Concepts (in French). Nouakchott, Mauritania. 2009. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

External links

- Malouma in concert (video)

- Malouma, profile and interview (video)

- Fondation Malouma Archived August 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Malouma, Mauritania's Biggest Musical Export Archived February 15, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (2010 audio produced by Global Notes)

- Paintings created by Sidi Yahya to illustrate Malouma's album Knou