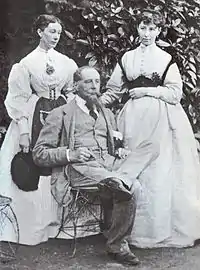

Mary Dickens

Mary "Mamie" Dickens (6 March 1838 – 23 July 1896) was the eldest daughter of the English novelist Charles Dickens and his wife Catherine. She wrote a book of reminiscences about her father, and in conjunction with her aunt, Georgina Hogarth, she edited the first collection of his letters.[1]

Mary Dickens | |

|---|---|

Mary "Mamie" Dickens | |

| Born | 6 March 1838 London |

| Died | 23 July 1896 (aged 58) Farnham Royal, Buckinghamshire |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Author |

| Parent(s) | Charles Dickens Catherine Hogarth |

| Signature | |

Childhood

Mamie Dickens was born at the family home in Doughty Street in London[2] and was named after her maternal aunt Mary Hogarth, who had died in 1837. Her godfather was John Forster, her father's friend and later biographer. Mary was nicknamed "Mild Glo'ster" by her father.[3] In December 1839 the Dickens family moved from 48 Doughty Street to 1 Devonshire Terrace. Of her childhood here she later wrote:

"I remember that my sister and I occupied a little garret room in Devonshire Terrace, at the very top of the house. He had taken the greatest pains and care to make the room as pretty and comfortable for his two little daughters as it could be made. He was often dragged up the steep staircase to this room to see some new print or some new ornament which we children had put up, and he always gave us words of praise and approval. He encouraged us in every possible way to make ourselves useful, and to adorn and beautify our rooms with our own hands, and to be ever tidy and neat. I remember that the adornment of this garret was decidedly primitive, the unframed prints being fastened to the wall by ordinary black or white pins, whichever we could get. But, never mind, if they were put up neatly and tidily they were always excellent, or quite slap-up as he used to say. Even in those early days, he made a point of visiting every room in the house once each morning, and if a chair was out of its place, or a blind not quite straight, or a crumb left on the floor, woe betide the offender."[4]

She and her younger sister Kate were taught to read by their aunt, Georgina Hogarth, who was now living with the family. Later they had a governess. In her book Charles Dickens by His Eldest Daughter (1885), she described her father's method of writing:

"As I have said, he was usually alone when at work, though there were, of course, some occasional exceptions, and I myself constituted such an exception ... I had a long and serious illness, with an almost equally long convalescence. During the latter, my father suggested that I should be carried every day into his study to remain with him, and, although I was fearful of disturbing him, he assured me that he desired to have me with him. On one of these mornings, I was lying on the sofa endeavouring to keep perfectly quiet, while my father wrote busily and rapidly at his desk, when he suddenly jumped from his chair and rushed to a mirror which hung near, and in which I could see the reflection of some extraordinary facial contortions which he was making. He returned rapidly to his desk, wrote furiously for a few moments, and then went again to the mirror. The facial pantomime was resumed, and then turning toward, but evidently not seeing, me, he began talking rapidly in a low voice. Ceasing this soon, however, he returned once more to his desk, where he remained silently writing until luncheon time. It was a most curious experience for me, and one of which, I did not until later years, fully appreciate the purport. Then I knew that with his natural intensity he had thrown himself completely into the character that he was creating, and that for the time being he had not only lost sight of his surroundings, but had actually became in action, as in imagination, the creature of his pen."[4]

In 1855 Charles Dickens took his two daughters to Paris. He told his friend Angela Burdett-Coutts that his intention was to give Mary (then aged 17) and Kate (aged 16) "some Parisian polish". While in France they had dancing lessons, art classes and language coaching. They also had Italian lessons from the exiled patriot Daniele Manin.[5]

She appeared in a number of amateur plays directed by her father, including Wilkie Collins's The Lighthouse in which Charles Dickens also acted along with Collins, Augustus Egg, Mark Lemon and Georgina Hogarth. The production ran for four nights from 16 June 1855 at Tavistock House, Dickens's home, followed by a single performance on 10 July at Campden House, Kensington.[6] In January 1857 she appeared in The Frozen Deep, again written by Collins and performed at Tavistock House before the Duke of Devonshire, Lord Lansdowne, Lord Houghton, Angela Burdett-Coutts and Edward Bulwer-Lytton.[7]

In 1857 Dickens was visited at Gads Hill Place by Danish author and poet Hans Christian Andersen, who was invited for two weeks but who stayed for five. Andersen described Mary as resembling her mother.[8] Author Peter Ackroyd described her as being "amiable, somewhat sentimental, but high-spirited and with a love for what might be called the life of London society. She seems to have attached herself to her father with an almost blind affection; certainly, she never married and, of all the children, she was the one closest to him for the rest of his life."[9]

After her parents separated in 1858 Mary Dickens and her aunt Georgina Hogarth were put in command of the servants and household management. She did not see her mother again until after her father's death in 1870.[10] Of her father's alleged affair with the actress Ellen Ternan, which has been cited as the reason for the break-up of Charles Dickens's marriage, biographer Lucinda Hawksley wrote:

"For Katey and Mamie, the knowledge that their father was sexually attracted to a girl their own age must have been utterly distasteful. Children are never happy to think about their parents' sex life and, in the nineteenth century, sex was a subject seldom discussed between the generations ... In a little over fifteen years, Catherine had given birth to ten children, as well as suffering at least two miscarriages. It is no wonder she did not have the energy of her childfree younger sister; nor that she lost the slim figure she had possessed when Charles married her. Towards the end of their marriage he had often made cruel jokes about her size and stupidity while praising Georgina to the hilt as his helpmeet and saviour. Both Katey and Mamie – by dint of being female – would undoubtedly have cringed at the way their father spoke about their mother and the way he made no secret of preferring the company of her sister, of Ellen and, for that matter, almost any other young attractive woman."[11]

Because Mary and Katey decided to stay with their father rather than with their mother they experienced a certain amount of social coldness. A relative of their mother wrote, "they, poor girls, have also been flattered as being taken notice of as the daughters of a popular author. He, too, is a caressing father and indulgent in trifles, and they in their ignorance of the world, look no further nor are aware of the injury he does them."[12] When Dickens decided to burn all his letters in 1860 in the field behind Gads Hill Place it was Mary and two of her brothers who carried them out of the house in basketfuls. These included correspondence from Alfred Tennyson, Thomas Carlyle, Thackeray, Wilkie Collins and George Eliot. Mary asked her father to keep some of them, but he refused, burning everything.[13]

In 1867 Mary was asked to name and launch a new ship at Chatham Dockyard, where her grandfather John Dickens had previously worked. She became a local celebrity in Kent, being the first woman there to be seen in public riding a bicycle.[14]

Mary Dickens became the official hostess at Gads Hill Place in Kent, Dickens's country home, staying with her father for the rest of his life. Her portrait was painted by John Everett Millais. She never married, although it is believed she received a proposal of marriage, which she refused because her father disapproved of the suitor. As a result, she suffered a prolonged bout of depression. However, Charles Dickens had hoped she would eventually marry and have children. In 1867 he wrote to a friend that Mary had "not yet started any conveyance on the road to matrimony." But he hoped that she still might, "as she is very agreeable and intelligent". He had suggested to her that his friend Percy Fitzgerald would make a good husband, but Dickens later wrote, "I am grievously disappointed that Mary can by no means be induced to think as highly of him as I do".[5]

Later years

After her father's death she lived with her brother Henry Dickens and her aunt, Georgina Hogarth;[15] In his will her father had written, "I give the sum of £1,000 free of legacy duty to my daughter Mary Dickens. I also give to my said daughter an annuity of £300 a year, during her life, if she shall so long continue unmarried; such annuity to be considered as accruing from day to day, but to be payable half yearly, the first of such half yearly payments to be made at the expiration of six months next after my decease."

Georgina Hogarth found living with Mary difficult, complaining that she was drinking too much.[16] With her aunt she edited two volumes of Dickens's letters, which were published in 1880. Later she seems to have embarrassed or angered her family, who largely cut themselves off from her.

Much of her life after her father's death in 1870 remains unknown, but after leaving her aunt's she lived for a period with a clergyman and his wife, Mr and Mrs Hargreaves, in Manchester, a "scandal" which was kept a secret by her family.[17] Later she lived alone in the country. Mary Dickens went on to write Charles Dickens By His Eldest Daughter (1885) and My Father As I Recall Him (1896), which was posthumously published and edited by her sister, Katey.[18]

On Mary's death her aunt, Georgina Hogarth, wrote to Connie Dickens, the widow of Edward Dickens:

"My love for Mamie as you know was most true and tender – so was her sister's and Harry's – But the loss – out of our lives – is not so great as it would have been years ago – For it is a long time since she ceased to be my companion. She had not lived in London for nearly 18 years. She was always dearly beloved whenever she came to see us – and stayed with us on special occasions. But she had given up all her family and friends for those people whom she had taken to live with her – Mr Hargreaves is a most unworthy person in every way – and it was always amazing to me that she could keep up this strong feeling and regard and affection for him to the very end of her life.

Mrs Hargreaves has kept true and devoted in her attentions to Mamie during her long illness – and Kitty and I were very grateful to her – I don't know what we could have done without her help at the last – we were thankful to have our darling Mamie all to ourselves – as both Mr and Mrs Hargreaves went away before she died – Kitty and I had been staying close by her for some time – and finally were always in her room – I don't know – and I don't care! what has become of Mr Hargreaves – I never want to meet his kind again – and I only hope and pray I never see him alive! She poor woman has been living since Mamie's death with some friends in the country and has two sisters who are very good to her – she is trying now to get some casual service as housekeeper or Companion and if Kitty or I can help or recommend her we shall be only too glad to do so – she has had a sad life – and will be much better without her detestable husband."[19]

Mary Dickens died in 1896 at Farnham Royal, Buckinghamshire, and is buried beside her sister Kate Perugini in Sevenoaks. She was buried on the same day as her eldest brother Charles Dickens Jr.[15]

Publications

- The Charles Dickens Birthday Book (London: Chapman & Hall), London. Illustrated by Kate Perugini (1882)

- The Letters of Charles Dickens Edited by his sister-in-law and his eldest daughter, 3 vols (Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1880)

- Charles Dickens By His Eldest Daughter (London: Cassell & Co, 1885)

- My Father As I Recall Him (Roxburghe Press, 1896)

- The Staircase of Fairlawn Manor (The Ladies Home Journal, 1891)

See also

Notes

- "The Letters of Charles Dickens" on Project Gutenberg

- Friends of the Charles Dickens Museum Lucinda Hawksley website

- Peter Ackroyd Dickens Published by Sinclair-Stevenson (1990), p. 452.

- Dickens, Mary Charles Dickens by His Eldest Daughter Cassell & Co, London (1885)

- Waddington, Patrick. 'Dickens, Pauline Viardot, Turgenev: A Study in Mutual Admiration', New Zealand Slavonic Journal, no. 1, 1974, pp. 55–73. JSTOR, Accessed 1 February 2021

- The Lighthouse website

- 'Charles Dickens' by Una Pope Hennessy Published by Chatto & Windus, London (1945) pg 360

- Ackroyd, pg 782

- Ackroyd, pg 877

- Henessey, pg 392

- Hawksley, Lucinda Katey: The Life and Loves of Dickens's Artist Daughter Published by Doubleday, (2006) ISBN 0-385-60742-3

- Backroom, pg 842

- Ackroyd, pg 882

- Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens Charles Dickens, Andre Deutsch (2011) pg 33

- The Family Tree of Charles Dickens by Mark Charles Dickens Published by the Charles Dickens Museum (2005)

- Cook, Susan E. Cook. Dickens Studies Annual, Penn State University Press Vol. 50, No. 1 (2019), pp. 130-203

- Hawksley, pg 34

- The Children of Charles Dickens

- Skelton, Christine. The Dickensian; London Vol. 113, Iss. 503, (Winter 2017): 252

External links

- Mary Dickens's biography on Spartacus Educational

- Photographs of Mary Angela Dickens at the National Portrait Gallery

- Works by Mamie Dickens at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mamie Dickens at Internet Archive

- Works by Mary Dickens at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Full text of 'My Father As I Recall Him' by Mamie Dickens Published by Dutton & Co. 1897

- 'Christmas With Dickens' By Mamie Dickens

- Mary Dickens at Find a Grave

- Article by Mamie Dickens in The New York Times 17 March 1884