Eliot Indian Bible

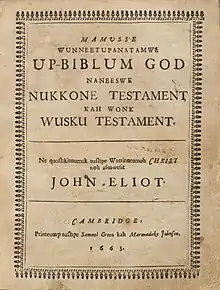

The Eliot Indian Bible (Massachusett: Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God;[1] also known as the Algonquian Bible) was the first translation of the Christian Bible into an indigenous American language, as well as the first Bible published in British North America. It was prepared by English Puritan missionary John Eliot by translating the Geneva Bible[2][3][4] into the Massachusett language.[5][6] Printed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the work first appeared in 1661 with only the New Testament. An edition including all 66 books of both the Old and New Testaments was printed in 1663.[7]

Algonquian Indian Bible title page 1663 | |

| Translator | John Eliot |

|---|---|

| Country | Colonial America |

| Language | Massachusett language |

| Subject | Bible |

| Genre | Christian literature |

| Publisher | Samuel Green |

Publication date | 1663 |

.jpg.webp)

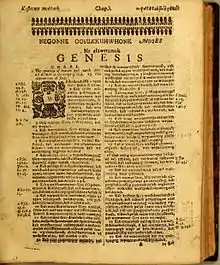

Old Testament first page of 1685 copy

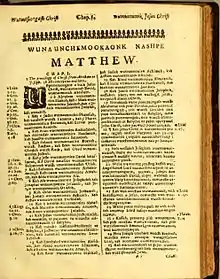

New Testament first page of 1685 copy

The inscription on the 1663 edition's cover page, beginning with Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up Biblum God, corresponds in English to The Whole Holy His-Bible God, both Old Testament and also New Testament. This turned by the servant of Christ, who is called John Eliot.[8] The preparation and printing of Eliot's work was supported by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England, whose governor was the eminent scientist Robert Boyle.

History

The history of Eliot's Indian Bible involves three historical events that came together to produce the Algonquian Bible.

America's first printing press

Stephen Daye of England contracted Jose Glover, a wealthy minister who disagreed with the religious teachings of the Church of England, to transport a printing press to America in 1638. Glover died at sea while traveling to America.[9] His widow Elizabeth (Harris) Glover, Stephen Daye, and the press arrived at Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Mrs. Glover opened her print shop with the assistance of Daye.[9] Daye started the operations of the first American print shop which was the forerunner of Harvard University Press.[9] The press was located in the house of Henry Dunster, the first president of Harvard College where religious materials such as the Bay Psalm Book were published in the 1640s. Elizabeth Glover married president of Harvard College Henry Dunster on June 21, 1641.[9]

Act of Parliament

In 1649 Parliament enacted An Act for the Promoting and Propagating the Gospel of Jesus Christ in New England,[10] which set up a Corporation in England consisting of a President, a Treasurer, and fourteen people to help them.[11] The name of the corporation was "The President and Society for the propagation of the Gospel in New England,"[11] but it was later known simply as the New England Company.[12] The corporation had the power to collect money in England for missionary purposes in New England.[11] This money was received by the Commissioners of the United Colonies of New England and dispersed for missionary purposes such as Eliot's Indian Bible.[13][11]

Arrival of John Eliot

Eliot came to the Massachusetts Bay Colony from England in 1631. One of his missions was to convert the indigenous Massachusett to Christianity.[6][14] Eliot's instrument to do this was through the Christian scriptures.[6] Eliot's feelings were that the Indians felt more comfortable hearing the scriptures in their own language than in English (a language they understood little of).[6] Eliot thought it best to translate the English Christian Bible to an Algonquian Bible rather than teach the Massachusett Indians English.[6] He then went about learning the Algonquian Indian language of the Massachusett people so he could translate English to the Natick dialect of the Massachusett language.[6] Eliot translated the entire 66 books of the English Bible in a little over fourteen years.[6][15] It had taken 44 scholars seven years to produce the King James Version of the Christian Bible in 1611.[6] Eliot had to become a grammarian and lexicographer to devise an Algonquian dictionary and book of grammar.[6] He used the assistance of a few local Massachusett Indians in order to facilitate the translation, including Cockenoe, John Sassamon, Job Nesuton, and James Printer.[6][16]

Eliot made his first text for the Corporation for the propagation of the Gospel in New England into the Massachusett language as a one volume textbook primer catechism in 1653 printed by Samuel Green.[17] He then translated and had printed in 1655-56 the Gospel of Matthew, book of Genesis, and Psalms into the Algonquian Indian language.[18][15] It was printed as a sample run for the London Corporation to show what a complete finished Algonquian Bible might look like.[19] The Corporation approved the sample and sent a professional printer, Marmaduke Johnson, to America in 1660 with 100 reams of paper and eighty pounds of new type for the printer involved to print the Bible.[6][20] To accommodate the transcription of the Algonquian Indian language phonemes extra "O's" and "K's" had to be ordered for the printing press.[6]

Johnson had a three-year contract to print the entire Bible of 66 books (Old Testament and New Testament).[19] In 1661, with the assistance of the English printer Johnson and a Nipmuc named James Printer, Green printed 1,500 copies of the New Testament.[6] In 1663 they printed 1,000 copies of the complete Bible of all 66 books (Old Testament and New Testament) in a 1,180 page volume.[7][6][21] The costs for this production was paid by the Corporation authorized by the Parliament of England by donations collected in England and Wales.[19] John Ratcliff did the binding for the 1663 edition.[22]

Description

Eliot was determined to give the Christian Bible to them in their own Massachusett language.[23] He learned the Natick dialect of the Massachusett language and its grammar.[23]

Eliot worked on the Indian Bible for over fourteen years before publication.[24] England contributed about £16,000 for its production by 1660. The money came from private donations in England and Wales. There was no donations or money from the New England colonies for Eliot's Indian Bible. The translation answered the question received many times by Eliot from the Massachusett was "How may I get faith in Christ?" The ecclesiastical answer was "Pray and read the Bible." After Eliot's translation, there was a Bible they could read.[25]

Eliot translated the Bible from an unwritten American Indian language into a written alphabet that the Algonquian Indians could read and understand.[25] To show the difficulty of the Algonquian language used in Eliot's Indian Bible Cotton Mather gives as an example the Algonquian word Nummatchekodtantamoonganunnonash (32 characters) which means "our lusts".[7] He said that the Indian language did not have the least affinity to or derivation from any European speech.[7]

Some ecclesiastical questions given to Eliot by the Natick Indians that were to be answered by the new Algonquian Bible and Indian religious learning were:

- If but one parent believe, what state are our children in?

- How doth much sinne make grace abound?

- If an old man as I repent, may I be saved?

- What meaneth that, Let the trees of the Wood rejoice?

- What meaneth that, We cannot serve two masters?

- Can they in Heaven see us here on Earth?

- Do they see and know each other? Shall I know you in heaven?

- Do they know each other in Hell?

- What meaneth God, when he says, Ye shall be my Jewels

- If God made hell in one of the six dayes, why did God make Hell before Adam had sinned?

- Doe not Englishmen spoile their souls, to say a thing cost them more then it did? and is it not all one as to steale?[26]

Legacy

In 1664 an especially prepared display copy was presented to King Charles II by Robert Boyle, the Governor of the New England Company.[27] Many copies of the first edition (1663) of Eliot’s Indian Bible were destroyed by the British in 1675-76 by a war against Metacomet (war chief of the Wampanoag Indians).[21][28] In 1685, after some debate, the New England Company decided to publish another edition of Eliot’s Indian Bible. [29] The second edition of the entire Bible was finished in 1686, at a fraction of the cost of the first edition.[30] There were 2,000 copies printed.[21] A special single leaf bearing a dedication to Boyle placed into the 1685 presentation copies that were sent to Europe.[31]

The first English edition of the entire Bible was not published in the colonies until 1752, by Samuel Kneeland.[32][33] Eliot's Indian Bible translation of the complete Christian Bible was supposedly written with one pen.[34] This printing project was the largest printing job done in 17th-century Colonial America.[12]

The Massachusett Indian language Natick dialect that the translation of Eliot's Bible was made in no longer is used in the United States.[34] The Algonquian Bible is today unreadable by most people in the world.[7] Eliot's Indian Bible is notable for being the earliest known example of the translation and putting to print the entire 66 books of the Christian Bible into a new language of no previous written words.[14] Eliot's Indian Bible was also significant because it was the first time the entire Bible was translated into a language not native to the translator. Previously scholars had translated the Bible from Greek, Hebrew, or Latin into their own language. With Eliot the translation was into a language he was just learning for the purpose of evangelization.[7]

In 1709 a special edition of the Algonquian Bible was authored by Experience Mayhew with the Indian words in one column and the English words in the opposite column. It had only Psalms and the Gospel of John. It was used for training the local Massachusett Indians to read the scriptures.[35] This Algonquian Bible was a derivative of Eliot's Indian Bible.[36] The 1709 Algonquian Bible text book is also referred to as The Massachuset psalter.[35] This 1709 edition is based on the King James Bible just like Eliot's Indian Bible (aka: Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up Biblum God).[5]

A second edition printing of Eliot's Indian Bible was an instrumental source for the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project where it was compared to the King James Bible in order to relearn Wôpanâak (Wampanoag) vocabulary and grammar.[37]

See also

- John Ratcliff (bookbinder)

- Pony Express Bible

- Early American publishers and printers

References

- Szasz 2007, p. 114.

- The KJV in Early America

- Genesis, John Eliot's Indian Bible, "The Bible favored by the Puritans was the Geneva Bible, particularly the 1611 translation"

- The Fascinating Story of the First American Bible, a Native American Language Translation from 1663

- Mayhew 2008, p. 64.

- Thorowgood 2003, p. 13.

- "The Eliot Indian Bible: First Bible Printed in America". Library of Congress Bible Collection. Library of Congress. 2012. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Walker, Williston (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 277–278.

- "Stephen Day". Britannica.com. Britannica.com. 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "John Eliot's Indian Bible. Cambridge, 1663, 1665, 1685". University of California - Berkeley. 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "An Act for the promoting and propagating the Gospel of Jesus Christ in New England". British History Online. University of London & History of Parliament Trust. 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Nord 2004, p. 20.

- Thomas, 1874, Vol. I, p. 67

- Rumball-Petre 2000, p. 8.

- Baker 2002, p. 180.

- Rumball-Petre 2000, p. 14.

- Round 2010, p. 26.

- Gregerson 2013, p. 73.

- Winship 1946, p. 208-244.

- "The Eliot Indian Bible: First Bible Printed in America". MyLOC. Library of Congress. 2013. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Deane, Charles (January 1, 1873). May Meeting, 1874. Letter of S. Danforth; Eliot's Indian Bible; Jasper Danckaerts; Dankers's Journal. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. p. 308. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Kane 1997, p. 65.

- American Indian 1974, p. 1111.

- Francis 1836, p. 235.

- Klauber 2008, p. 28.

- Baker 2002, p. 180-191.

- Massachusetts Historical Society 1862, p. 376.

- Stone 2010, p. 82.

- Thorowgood 2003, p. 14.

- Beach 1877, p. 411.

- Eliot, John, 1604-1690; Cotton, John, 1640-1699; Company for Propagation of the Gospel in New England and Parts Adjacent in America (1685). "Mamusse wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God naneeswe Nukkone Testament kah wonk Wusku Testament. (1685)". Internet Archive. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Printer - Samuel Green. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Newgass, 1958, p. 32

- Thomas, 1874, Vol. I, pp. 107-108

- U.S. Government Printing Office 1898, p. 14.

- "The Massachuset psalter: or, Psalms of David with the Gospel according to John, in columns of Indian and English: Being an introduction for training up the aboriginal natives, in reading and understanding the Holy Scriptures (1709)". Internet Archive. Boston: Printed by B. Green, and J. Printer, for the Honourable Company for the Propagation of the Gospel in New-England. 1709. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Mayhew, Experience, 1673-1758 + Eliot, John, 1604-1690 (1709). "The Massachuset psalter or, Psalms of David with the Gospel according to John, in columns of Indian and English. [microform] : Being an introduction for training up the aboriginal natives, in reading and understanding the Holy Scriptures". Boston, N.E. : Printed by B. Green, and J. Printer, for the Honourable Company for the Propagation of the Gospel in New-England. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mifflin, Jeffrey (April 22, 2008). "Saving a Language". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

Bibliography

- American Indian, Culture and Research Journal (1974). American Indian Culture and Research Journal. American Indian Culture and Research Center, University of California.

- Baker, David J. (2002). British Identities and English Renaissance Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78200-5.

- Beach, William Wallace (1877). The Indian Miscellany: Containing Papers on the History, Antiquities, Arts, Languages, Religions, Traditions and Superstitions of the American Aborigines ; with Descriptions of Their Domestic Life, Manners, Customs, Traits, Amusements and Exploits ; Travels and Adventures in the Indian Country ; Incidents to Border Warfare; Missionary Relations, Etc. J. Munsell. p. 411.

- Francis, Convers (1836). Life of John Eliot, the Apostle to the Indians. Hilliard, Gray. ISBN 9780722285497.

- Gregerson, Linda (10 April 2013). Empires of God: Religious Encounters in the Early Modern Atlantic. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-2260-9.

- Kane, Joseph (1997). Famous First Facts, A Record of First Happenings, Discoveries, and Inventions in American History (5th ed.). H.W. Wilson Company. p. 65, item 1731. ISBN 0-8242-0930-3.

The first bookbinder was John Ratliffe of Massachusetts, who in 1663 was commissioned to bind missionary John Eliot's Algonkian translation of the Bible. His job was to "take care of the binding of 200 of them strongly and as speedily as may bee with leather, or as may bee most serviceable for the Indians." On August 30, 1664, he sent a letter to the commissioners of New England stating that he was not well satisfied with the fees paid him for binding, and that three shillings four pence was the lowest price at which he could bind the books.

- Klauber, Martin I. (1 April 2008). The Great Commission: Evangelicals and the History of World Missions. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8054-4300-4.

- Massachusetts Historical Society (1862). Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. The Society.

- Mayhew, Experience (2008). Experience Mayhew's Indian Converts: A Cultural Edition. Univ of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-661-3.

- Nord, David Paul (23 July 2004). Faith in Reading : Religious Publishing and the Birth of Mass Media in America: Religious Publishing and the Birth of Mass Media in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803861-0.

- Round, Phillip H. (11 October 2010). Removable Type: Histories of the Book in Indian Country, 1663-1880. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-9947-2.

- Rumball-Petre, Edwin A. R. (2000). America's First Bibles: With a Census of 555 Extant Bibles. Martino Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57898-260-8.

- Stone, Larry (21 September 2010). The Story of the Bible: The Fascinating History of Its Writing, Translation & Effect on Civilization. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-1-59555-119-1.

- Szasz, Margaret (2007). Indian Education in the American Colonies, 1607-1783. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-5966-9.

- Thomas, Isaiah (1874). The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers. To which is Prefixed a Concise View of the Discovery and Progress of the Art in Other Parts of the World. In Two Volumes. From the Press of Isaiah Thomas, jun. Isaac Sturtevant, Printer.

- Thorowgood, Thomas (2003). The Eliot Tracts: With Letters from John Eliot to Thomas Thorowgood and Richard Baxter. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30488-0.

- U.S. Government Printing Office (1898). Congressional Edition. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Winship, George Parker (1946). The Cambridge Press, 1638-1692: A Reëxamination of the Evidence Concerning the Bay Psalm Book and the Eliot Indian Bible as Well as Other Contemporary Books and People. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Further reading

- De Normandie, James (July 1912). "John Eliot, the Apostle to the Indians". The Harvard Theological Review. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Harvard Divinity School. 5 (3): 349–370. doi:10.1017/S0017816000013559. hdl:2027/nnc2.ark:/13960/t2m68w501. JSTOR 1507287. S2CID 162354472.

- Cogley, Richard W. (Summer 1991). "John Eliot and the Millennium". Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation. University of California Press on behalf of the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture. 1 (2): 227–250. JSTOR 1123872.

External links

- Stories of Eliot and the Indians

- Complete Algonquian Indian Bible 1663

- Complete Algonquian Indian Bible 1685

- Education And Harvard's Indian College

- Psalms of David with the Gospel according to John, in columns of Indian and English

- A Sketch of the Life of the Apostle Eliot: Prefatory to a Subscription for Erecting a Monument