Mandingo (novel)

Mandingo is a novel by Kyle Onstott, published in 1957. The book is set in the 1830s in the Antebellum South primarily around Falconhurst, a fictional plantation in Alabama owned by the planter Warren Maxwell. The narrative centers on Maxwell, his son Hammond, and the Mandingo slave Ganymede, or Mede. Mandingo is a tale of cruelty toward the black people of that time and place, detailing the overwhelmingly dehumanizing behavior meted out to the slaves, as well as vicious fights, poisoning, and violent death. The novel was made into a film of the same name in 1975.

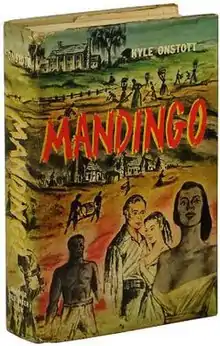

First edition | |

| Author | Kyle Onstott |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Denlinger's |

Publication date | 1957 |

| Pages | 659 |

| OCLC | 2123289 |

Author

Kyle Elihu Onstott was born on January 12, 1887, in Du Quoin, Illinois.[1] Although he never had a steady job, Onstott was from an affluent family, and, living with his widowed mother in California in the early 1900s, was able to pursue his main hobby, that of a dog breeder and judge in regional dog shows, in lieu of any professional calling.

Onstott was a lifelong bachelor, but at age 40, he chose to adopt a 23-year-old college student, Philip, who had lost his own parents. Philip eventually married a woman named Vicky and the two remained close to Onstott for the rest of his life. Onstott dedicated Mandingo to Philip and Vicky.[2]

Onstott began writing Mandingo when he was 65 years old. He based some of the events in the novel on "bizarre legends" he heard while growing up: tales of slave breeding and sadistic abuse of slaves. Having collaborated with his adopted son on a book about dog breeding, he decided to write a book that would make him rich. "Utilizing his [adopted] son's anthropology research on West Africa, he handwrote Mandingo and his son served as editor. Denlinger's, a small Virginia publisher, released it and it became a national sensation."[3] He was invited to write an article for True: The Man's Magazine in 1959 about the horrors of slavery.[4]

Publication

Mandingo was first published in 1957 in hardcover. It was 659 pages long and sold around 2.7 million copies. Subsequent paperback editions whittled the novel down to 423 pages.[5] The novel sold a total of 5 million copies in the United States.[6]

Mandingo is the only novel of the Falconhurst series that Onstott wrote, but he edited the next three novels in the series. All of the sequels were penned by either Lance Horner or Henry Whittington (Ashley Carter).[7]

Plot

Mandingo takes place in 1832 on the fictional plantation Falconhurst, located close to Tombigbee River near Benson, Alabama. Warren Maxwell is the elderly and infirm owner of Falconhurst and he lives there with his 19-year-old son, Hammond. Falconhurst is a slave-breeding plantation where slaves are encouraged to mate and produce children ("suckers"). Because of the nature of the plantation, the slaves are well fed, not overworked, and rarely punished in a brutal manner. However, the slaves are treated as animals to be utilized as the Maxwells wish. Warren Maxwell, for example, sleeps with his feet against a naked slave to drain his rheumatism.

Although Hammond keeps a "bed-wench" for sexual satisfaction, his father wishes him to marry and produce a pure white heir. Hammond is skeptical and is not sexually attracted to white women. Despite his misgivings, he travels to his Cousin Beatrix's plantation, Crowfoot, and there meets his 16-year-old cousin, Blanche. He asks Blanche's father, Major Woodford, permission to marry her within four hours of meeting her. After receiving the Major's permission, Hammond and Charles Woodford, Blanche's brother, travel to the Coign plantation where Hammond purchases a "fightin' nigger", Ganymede (aka Mede), and a young, female slave named Ellen. Later, Hammond reveals his love for Ellen, despite his intentions to wed Blanche.

Back at Falconhurst, Hammond and Warren mate Mede, a pure Mandingo slave, with Big Pearl, another Mandingo slave. It turns out that Mede and Big Pearl are brother and sister, but no one shows concern over the incestuous act. Charles and Hammond take Mede to a bar to fight with other slaves. Hammond plans to use his winnings to buy a diamond ring for Blanche. When it is Mede's turn to fight, he easily beats the other slave, Cudjo, in 20 seconds and neither man is seriously injured. Mede is clearly an extremely strong and powerful man.

Hammond sets off with his "body nigger", Omega (Meg), to the Crowfoot plantation to wed Blanche. Once he arrives at Crowfoot, Hammond learns that Charles never returned to the plantation, taking with him $2,500 that Hammond loaned Major Woodford and the diamond ring for Blanche. Despite the confusion, the Major consents to let Blanche and Hammond marry. They do so that evening, with Dick Woodford (Blanche's brother, a preacher) performing the ceremony.

On their wedding night, Hammond leaves his and Blanche's room in the middle of the night. Hammond believes that Blanche is not a virgin. Although she denies having previous sex partners, it turns out that Blanche lost her virginity to her brother, Charles, at age 13. She does not reveal this fact to Hammond.

After a few months at Falconhurst, Blanche is bored and dissatisfied. She begins drinking heavily and is jealous of Hammond's continuing preference for his "bed wench", Ellen, who is now pregnant. Soon, Blanche is also pregnant.

Hammond and Warren take Mede to another slave fight, where Mede is nearly beaten by a stronger slave, Topaz, but ends up killing Topaz by biting through his jugular vein. Later, Hammond travels again, this time to Natchez, Mississippi, to sell a coffle of slaves. When Blanche reveals her fear that Hammond will sleep around with "white whores", Hammond bluntly states, "White ladies make me puke."[8]

While Hammond is away, Blanche calls Ellen to her room and whips her. Ellen miscarries and it is unclear whether her miscarriage is caused by the whipping.

While in Mississippi, Hammond sells one of his male slaves to a German woman, who obviously wants the slave for sex. When the other men in the group explain this to Hammond, he is physically repulsed and denies that a white woman would ever willingly sleep with a black slave.

Blanche has her baby, a girl, Sophy. Despite giving birth and Ellen's miscarriage, Blanche's jealousy of Ellen continues to grow. When Hammond travels to an estate auction and secretly takes Ellen along, Blanche becomes apoplectic. She orders Mede to come to her room and have sex with her. Before he leaves, she forcibly pierces Mede's ears with a pair of earrings Hammond gave her. This is a particularly poignant act of retaliation against Hammond because he bought an identical pair of earrings for Ellen.

Blanche becomes pregnant again and does not know if the baby is Mede's or Hammond's. She realizes it is too late to accuse Mede of rape. In the final chapter of the book she gives birth and the child is dark-skinned and looks like Mede. Blanche's mother, visiting Falconhurst, kills the baby by crushing its skull. When Hammond finds out, he calmly asks the doctor for some poison, mixes it in a hot toddy, and gives it to Blanche, killing her. He then boils water in a giant kettle and forces Mede to get in. When Mede resists, he uses a pitchfork to stab the slave to death and then orders the other slaves to keep the fire going, thus turning Mede into a soup. The novel ends with Hammond and Warren discussing Hammond's plans to leave Falconhurst and forge a new life out west.

Themes

Slave breeding

In Slave Breeding: Sex, Violence, and Memory in African American History, Gregory Smithers traces the history of coercive reproductive and sexual practices in the Antebellum South, as well as reactions and denials of the practice of slave breeding by historians throughout the twentieth century. Smithers goes into great detail about Mandingo, a novel that is explicitly about slave breeding. In the novel, Warren Maxwell, owner of the Falconhurst plantation, reiterates time and again that cotton is not a reliable crop and the real money is in breeding "niggers". Over the course of the novel, four female slaves give birth (and another miscarries), and in each instance the Maxwells give the slaves a dollar and a new dress. The Maxwells, particularly the elder Warren, wax poetic about slave breeding, arguing that while slaves with white (or "human" as the Maxwells put it in the novel) blood are smarter and better looking, purebred Mandingos are among the strongest and most submissive slaves. While Hammond Maxwell is more interested in satisfying his own sexual appetites and preparing his prize slave, Mede, for fights, Warren Maxwell spends much time planning how to mate various slaves to produce the best "suckers". There is much discussion over the virility of male slaves, such as when the cook, Lucretia Borgia, and Warren Maxwell have a discussion about who the father of her baby is:

"So that Napoleon boy I give you had a nigger in him after all? A long time comin' out," commented Maxwell. "I reckons I didn't git it from 'Poleon. That squirt no good. This baby is Memnon's, I figures. Masta Ham tole me to try Memnon agin, and I been pesterin' with him fer about a month."[9]

Such discussions of intimate details of slave bodies, genitals, and sexuality are rampant throughout the novel, and the reader becomes aware that for a slave at Falconhurst, nothing is private or sacred—not even sexual intimacy.

Kyle Onstott's lifelong interest in dog breeding most certainly affected the theme of breeding slaves and slave typologies in Mandingo. Onstott even comments on this in a Newsweek article about Mandingo: "I've always felt that the human race could be regenerated by selective breeding. But Mandingo isn't the sort of thing I mean."[10]

Sexual relations between white men and black women

In Mandingo, it is expected and assumed that white men will sleep with their own and others' female slaves. In addition to keeping a "bed wench" at home, when Hammond Maxwell travels to various locations, his hosts usually offer a slave to sleep with, along with dinner and a bed. When he visits the Woodfords and meets his future wife, Blanche, Hammond shares a bed with Charles Woodford and is given a slave to have sex with. While Hammond kicks the slave, Sukey, out of bed when he is done with her, he is shocked that Charles and his "bed wench", Katy, have sex—including kissing on the mouth—right next to him.[11] Later, when Charles and Hammond travel to the Coign plantation, the owner, Mr. Wilson, gives Hammond a slave, Ellen, to sleep with.[12] Hammond ends up falling in love and buying Ellen from Wilson.

The white men in Mandingo take for granted their entitlement to sleep with female slaves, and offering a "bed wench" to a (male) guest is part of the code of southern hospitality. However, there are limits to the actions and feelings that are acceptable between black women and white men. As pointed out above, Hammond is shocked when he sees Charles and Katy kiss on the lips:

"It was disgust, bordering upon nausea, that a white man should assume an amatory equality with a Negro wench. It was beneath the dignity of his race—somehow bestial. A wench was an object for a white man's use when he should need her, not a goal of his affections, to be commanded and not to be wheedled."[13]

Later, when Hammond is married to Blanche, yet still sleeping with Ellen almost every night, Blanche is upset not because her husband sleeps with female slaves, but because he sleeps with one female slave: "Her husband's philandering with his wenches she would not have resented, but his dalliance with a single wench aroused her ire."[14] Blanche's anger at Hammond and jealousy of Ellen grow throughout the final third of the book until she retaliates by sleeping with the Mandingo slave, Mede. But unlike a white man having sex with a black woman, a white woman voluntarily having sex with a black man is so beyond the parameters of acceptable behavior, it can only be punished by death.

Sexual relations between white women and black men

The cultural taboo of white women having sex with black male slaves in Mandingo is filtered through the mind and experiences of Hammond Maxwell. The issue is not brought up until chapter 35, when Hammond sells a male slave to a German woman. The men Hammond is with understand and are amused by the fact that the woman is obviously buying the slave for sex. Hammond does not realize this at first and when he is made aware of it, his first instinct is denial: "'You gen'lemen wrong,' said Hammond. 'She white, an' ain't no white lady goin' to pester with no nigger buck. You wrong.'"[15] When he comes to accept the obvious, he becomes physically ill: "He lay awake, obsessed and horrified by the fantasy of the German woman in the black man's arms."[16] Hammond's repulsion foreshadows his own fate: his wife sleeping with and bearing the child of his own prize "nigger buck".

After Blanche sleeps with Mede, she pierces his ears with the earrings Hammond got for her (of which there was an identical pair for Ellen) as a way to "mark" Mede as hers and also retaliate at Hammond. Hammond sees Mede wearing the earrings as Blanche's silly form of revenge and it amuses him: "...but that there was more to the story never entered his imagination. That his wife, a white woman, should have willing carnal commerce with a Negro...was literally unthinkable, and Hammond did not think it."[17] When the evidence of Blanche's affair comes forth in the form of a black baby, Hammond immediately asks the doctor for poison to kill Blanche. Although he certainly does not announce his intentions, both the doctor and his father know he is going to murder Blanche and neither one stops him because "who could blame the young husband?"[18] The calmness with which Hammond poisons Blanche and then gruesomely murders Mede by boiling him alive in a kettle reveals that, at least in the world of Mandingo, for a white lady to sleep with a black man was beyond taboo; it was a crime against nature so ghastly that immediate death for both parties was the only possible consequence. "There ain't no other way" explains Hammond to Warren.[18]

Earl Bargainnier points out that the trope of the sexually insatiable and adulterous white woman is very common in all the Falconhurst novels, not just Mandingo, and that these white female characters have an intense lust for black men. Bargainnier explains,

"These unattractive representations of southern white women as sexually insatiable and totally unfaithful...are also meant to destroy the earlier image of the chaste and delicate plantation belle of Thomas Nelson Page and numerous other authors of moonlight and magnolias fiction."[19]

Tim A. Ryan echoes this statement, writing, "Kyle Onstott's sensationalist Mandingo (1957) turns the myth of Tara on its head with unashamed vulgarity."[20] And the myth extended beyond literature to real life beliefs about the Antebellum South. Smithers writes that "Two of the most enduring fictions to emerge in Lost Cause mythology were the trope of the chivalrous white southern male and the dutiful (and asexual) white woman."[21] That Onstott so thoroughly skewered these beloved beliefs of those who glamorized the Antebellum South shows how radical a novel Mandingo was, despite its flaws.

Critical reactions

Although Mandingo was a national and international best-seller, selling 5 million copies nationwide,[22] critical opinions about the novel were—and continue to be—mixed. While black novelist Richard Wright praised Mandingo as "a remarkable book based on slave period documents",[23] other critics have deemed the book sensationalist and offensive. Van Deburg writes that "None of the three contributors to the [Falconhurst] series could be considered knowledgeable about the black experience"[24] and argued that "The Falconhurst novels reveled in white sexual exploitation of black slaves."[25] Van Deburg's use of the word "reveled" suggests that the authors of the Falconhurst series wrote mainly to titillate the audience rather than to criticize the culture of American slavery. Seidel writes off the character of Blanche as a nymphomaniac without considering the character's complexities.[26] In a 1967 New York Times article about American books published in France, Jacques Cabau refers to Mandingo as "a sort of Uncle Sade's Cabin that reflects less on racism than on its readers' perversion."[27] Eliot Fremont-Smith, a New York Times critic, mocked the Falconhurst series by using them as a litmus test for other "bad" fiction: "I am compelled to name the absolute worst, most regurgitory new-and-advertised book that I've read in 1975, the one most deserving of the Kyle Onstott Memorial Award..."[28]

Such critical reactions show a disgust at the atrocities portrayed in Onstott's novel. However, Paul Talbot points out that some contemporary reviews accepted the novel as shocking, yet truthful. He quotes Earl Conrad of The Negro Press: "Mandingo has aroused in me a wild enthusiasm. It is just about the most sensational, yet the truest book I have ever read..."[29] He quotes John Henry Faulk, a TV humorist who praised Mandingo as "...one of the most compellingly powerful novels I have ever read."[30] Nearly all critics were quick to point out the "morbid, revolting, interesting, sadistic..."[31] nature of the content while also accepting Onstott's vision of the Antebellum South as accurate: "...it carries with it the power of absolute conviction, and this quality may demand that we revise our notions of American history, for it confounds us with the evils of our past."[32] It seems that whatever opinion critics had of Mandingo, they could not deny its emotional impact on readers and its challenge to the romanticization of the Antebellum South.

Legacy

Adaptations

A play based on the novel and written by Jack Kirkland opened at the Lyceum Theater in New York in May, 1961, with Franchot Tone and Dennis Hopper in the cast; it ran for only eight performances.[33] The novel and play were the basis for the 1975 Paramount Pictures film Mandingo.[34]

Literary sequels and prequels

Mandingo was followed by several sequels over the next three decades, some of which were co-written by Onstott with Lance Horner and in later years written by Harry Whittington under the pseudonym "Ashley Carter".

In order by publication date:[35]

- Mandingo (1957)

- Drum (1962)

- Master of Falconhurst (1964)

- Falconhurst Fancy (1966)

- The Mustee (1967)

- Heir to Falconhurst (1968)

- Flight to Falconhurst (1971)

- Mistress of Falconhurst (1973)

- Six-Fingered Stud (1975)

- Taproots of Falconhurst (1978)

- Scandal of Falconhurst (1980)

- Rogue of Falconhurst (1983)

- Miz Lucretia of Falconhurst (1985)

- Mandingo Master (1986)

- Falconhurst Fugitive (1988)

In order of internal series chronology:

- Falconhurst Fancy (1966)

- Mistress of Falconhurst (1973)

- Mandingo (1957)

- Mandingo Master (1986)

- Flight to Falconhurst (1971)

- Six-Fingered Stud (1975)

- Rogue of Falconhurst (1983)

- Falconhurst Fugitive (1988)

- Miz Lucretia of Falconhurst (1985)

- The Mustee (1967)

- Taproots of Falconhurst (1978)

- Scandal of Falconhurst (1980)

- Drum (1962)

- Master of Falconhurst (1964)

- Heir to Falconhurst (1968)

References

- Kaser, James A. (2014). The New Orleans of Fiction: A Research Guide. Scarecrow Press. p. 288. ISBN 9780810892040. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Talbot 2009, p.5

- Article by Rudy Maxa, "The Master of Mandingo", The Washington Post, July 13, 1975.

- Talbot 2009, pp. 3, 6

- Talbot 2009, pp. 18, 22, 24

- Smithers 2012, p. 152

- Bargainnier 1976, p. 298

- Onstott 1957, p. 475

- Onstott 1957, p. 31

- "Best-Seller Breed, The" 1957, p. 122

- Onstott 1957, pp.133-134

- Onstott 1957, p. 157

- Onstott 1957, p.134

- Onstott 1957, p. 405

- Onstott 1957, p. 508

- Onstott 1957, p. 510

- Onstott 1957, p. 614

- Onstott 1957, p. 644

- Bargainnier 1976, pp. 304–305

- Ryan 2008, p. 73

- Smithers 2012, p. 53

- Smithers 2012, p. 152-152

- Harrington as cited in Smithers 2012, p.153

- Van Deburg 1984, p.148

- Van Deburg 1984, p.149

- Seidel 1985, p. xii

- Cabau 1967, p. 36

- Fremont-Smith as cited in Bargainnier 1976, p. 299

- Conrad as cited in Talbot 2009, p. 19

- Faulk as cited in Talbot 2009, p.20

- Lexington, Kentucky Herald-Leader as cited in Talbot 2009, p. 20

- Price as cited in Talbot 2009, pp.20-21

- "Mandingo". Playbill. 1961.

- Paul Brenner (2013). "Mandingo". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-10-23.

- Talbot 2009, pp.267-270

Further reading

- Ryan, Tim A. (2008). Calls and Responses: The American Novel of Slavery since Gone with the Wind. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3322-4.