Surrealist Manifesto

The Surrealist Manifesto refers to several publications by Yvan Goll and André Breton, leaders of rival Surrealist groups. Goll and Breton both published manifestos in October 1924 titled Manifeste du surréalisme. Breton wrote his second manifesto for the Surrealists in 1929 (published in 1930), and later wrote his third manifesto in 1942.[1][2]

| Part of a series on |

| Surrealism |

|---|

Clashing manifestos

Leading up to 1924, two rival surrealist groups had formed. Each group claimed to be successor of a revolution launched by Guillaume Apollinaire. One group, led by Yvan Goll, consisted of Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Dermée, Céline Arnauld, Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pierre Reverdy, Marcel Arland, Joseph Delteil, Jean Painlevé and Robert Delaunay, among others.[4]

The other group, led by Breton, included Louis Aragon, Robert Desnos, Paul Éluard, Jacques Baron, Jacques-André Boiffard, Jean Carrive, René Crevel and Georges Malkine, among others.[5]

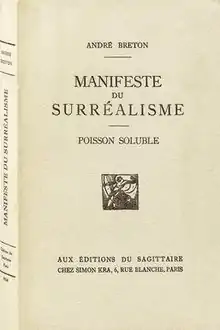

Yvan Goll published the Manifeste du surréalisme, 1 October 1924, in his first and only issue of Surréalisme[3] two weeks prior to the release of Breton's Manifeste du surréalisme, published by Éditions du Sagittaire, 15 October 1924.

Goll and Breton clashed openly—at one point, they literally fought at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées[4]—over the rights to the term "Surrealism." In the end, Breton won the battle through tactical and numerical superiority.[6][7] The quarrel over who first described Surrealism as an artistic movement concluded with Breton's victory.[2][1] Still, the history of surrealism remained marked by fractures, resignations, and resounding ex-communications, with each surrealist having their view of the issue and goals, and yet accepting, more or less, the definitions laid out by André Breton.[8][9]

Breton's 1924 manifesto

Breton wrote another Surrealist manifesto, also published in 1924 as a booklet (Editions du Sagittaire). The document defines Surrealism as:

Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.[10][11]

The text includes numerous examples of the applications of Surrealism to poetry and literature, but makes it clear that its basic tenets can be applied to any circumstance of life; not merely restricted to the artistic realm. The importance of the dream as a reservoir of Surrealist inspiration is also highlighted.

Breton also discusses his initial encounter with the surreal in a famous description of a hypnagogic state that he experienced in which a strange phrase inexplicably appeared in his mind: "There is a man cut in two by the window". This phrase echoes Breton's apprehension of Surrealism as the juxtaposition of "two distant realities" united to create a new one.

The manifesto also refers to the numerous precursors of Surrealism that embodied the Surrealist spirit, including the Marquis de Sade, Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud, Comte de Lautréamont, Raymond Roussel, and Dante. The works of several of his contemporaries in developing the Surrealist style in poetry are also quoted, including Philippe Soupault, Paul Éluard, Robert Desnos and Louis Aragon.

The manifesto was written with a great deal of absurdist humor, demonstrating the influence of the Dada movement which preceded it.

The text concludes by asserting that Surrealist activity follows no set plan or conventional pattern, and that Surrealists are ultimately nonconformists.

The manifesto named the following, among others, as participants in the Surrealist movement: Louis Aragon, André Breton, Robert Desnos, Paul Éluard, Jacques Baron, Jacques-André Boiffard, Jean Carrive, René Crevel and Georges Malkine.[12]

Breton's later manifestos

In 1929, Breton asked Surrealists to assess their "degree of moral competence", and along with other theoretical refinements issued the Second manifeste du surréalisme (1930).[2] The manifesto excommunicated Surrealists reluctant to commit to collective action: Baron, Robert Desno, Boiffard, Michel Leiris, Raymond Queneau, Jacques Prévert and André Masson. A prière d'insérer (printed insert) published with the Manifesto's release was signed by those Surrealists who remained loyal to Breton, and who had decided to participate in a new publication titled Surrealism at the Service of the Revolution.

Participants, and thus loyal Surrealists, included Maxime Alexander, Louis Aragon, Joe Bousquet, Luis Buñuel, René Char, René Crevel, Salvador Dalí, Paul Eluard, Max Ernst, Marcel Fourrier, Camille Goemans, Paul Nougé, Benjamin Péret, Francis Ponge, Marko Ristić, Georges Sadoul, Yves Tanguy, André Thirion, Tristan Tzara and Albert Valentin.[13] Along with Ristić, the Belgrade surrealists grouped around Nadrealista Danas i Ovde were aligned with Breton.[14]

Desnos and others thrown out by Breton moved to the periodical Documents, edited by Georges Bataille, whose anti-idealist materialism produced a hybrid Surrealism exposing the base instincts of humans.[15][16]

Breton wrote another manifesto on Surrealism in 1942.[1]

References

- "Breton, André (1896 - 1966) | The Bloomsbury Guide to Art - Credo Reference". search.credoreference.com. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- Foundation, Poetry (2023-08-16). "André Breton". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- Surréalisme, Manifeste du surréalisme, Volume 1, Number 1, 1 October 1924, Blue Mountain Project

- Gérard Durozoi, An excerpt from History of the Surrealist Movement, Chapter Two, 1924-1929, Salvation for Us Is Nowhere, translated by Alison Anderson, University of Chicago Press, pp. 63–74, 2002 ISBN 978-0-226-17411-2

- André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, transl. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor, 1971), p. 26.

- Matthew S. Witkovsky, Surrealism in the Plural: Guillaume Apollinaire, Ivan Goll and Devětsil in the 1920s, 2004

- Eric Robertson, Robert Vilain, Yvan Goll – Claire Goll: Texts and Contexts, Rodopi, 1997 ISBN 0854571833

- Man Ray / Paul Eluard – Les Mains libres (1937) – Qu'est-ce que le surréalisme ?

- Denis Vigneron, La création artistique espagnole à l'épreuve de la modernité esthétique européenne, 1898–1931, Editions Publibook, 2009 ISBN 2748348346

- "Surrealism". MOMA Learning, accessed 18 Oct. 2016.

- "". "Manifesto of Surrealism, English translation," accessed 16 Aug. 2023

- 'André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, transl. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor, 1971), p. 26.

- Gérard Durozoi, History of the Surrealist Movement, transl. Alison Anderson (Chicago, 2002), p. 193.

- Todic, Milanka (2002). Impossible: Art of Surrealism. Belgrade: Museum of Applied Art.

- Dawn Adès, with Matthew Gale: "Surrealism", The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Ed. Hugh Brigstocke. Oxford University Press, 2001. Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2007. Accessed March 15, 2007, http://www.groveart.com/

- Surrealist Art Archived 2012-09-18 at the Wayback Machine from Centre Pompidou. Accessed March 20, 2007

External links

- Andre Breton's Surrealist Manifesto

- The Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)

- Complete text of the Surrealist Manifesto

- Full text: Manifeste du surréalisme (French)

- Manifeste du surréalisme, André Breton, various editions, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

- Manifeste du surréalisme, University of Hong Kong, french

- "9 Manuscripts by André Breton at Sotheby's Paris" (in English and French). ArtDaily.org. 2008-05-20. cover, text