Lajonkairia lajonkairii

Lajonkairia lajonkairii is an edible species of saltwater clam in the family Veneridae, the Venus clams.[1]

| Lajonkairia lajonkairii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Venerida |

| Superfamily: | Veneroidea |

| Family: | Veneridae |

| Genus: | Lajonkairia |

| Species: | L. lajonkairii |

| Binomial name | |

| Lajonkairia lajonkairii (Payraudeau, 1826) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Common names for the species include Manila clam, Japanese littleneck clam, Japanese cockle,[2]Japanese carpet shell.,[1] and Bajirak(name called by koreans)[3][4][5]

This clam is commercially harvested, being the second most important bivalve grown in aquaculture worldwide.[6]

Description

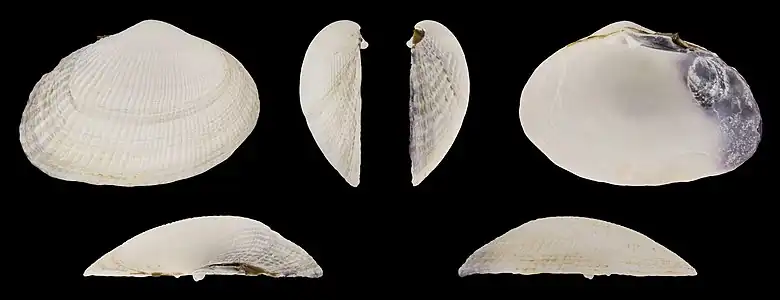

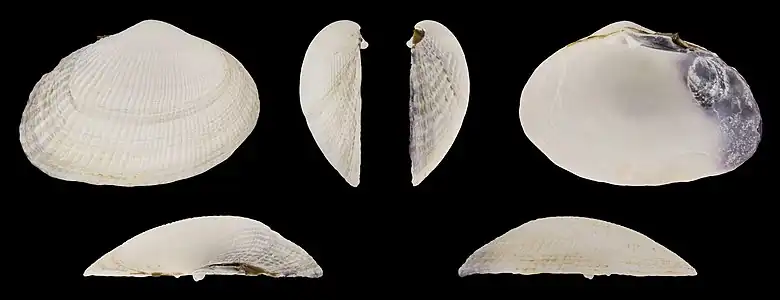

The shell of Lajonkairia lajonkairii is elongated, oval, and sculptured with radiating ribs.[7] It is generally 40 to 57 millimeters wide, with a maximum width of 79 millimeters.[8] The shell is variable in color and patterning, being cream-colored to gray with concentric lines or patches. Individuals living in anoxic conditions may be black. The inside surface of the shell is often white with purple edges.[8] The siphons are separated at the tips.[9]

Distribution

This clam is native to the coasts of the Indian, Philippines and Pacific Oceans from Pakistan and India north to China, Japan, Korea and the Kuril Islands.[10] It has an extensive nonnative distribution, having been introduced accidentally and purposely as a commercially harvested edible clam. It is now permanently established in coastal ecosystems in many parts of the world. It is common along the Pacific coast of North America from British Columbia to California, where its original introduction was accidental. It can be found in Hawaii. It was first seeded in the waters of Europe in the 1970s, and there have been multiple introductions throughout the region. It has spread naturally in Western Europe over the decades, its adaptability allowing it to thrive in many coastal habitat types. It has been planted in Portugal, Spain, the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Morocco, Israel, and French Polynesia for the purposes of aquaculture.[10]

Habitat

This burrowing clam is most abundant in subtropical and cooler temperate areas. It can be found in shallow waters in coarse sand, mud, and gravel substrates.[8] It lives in the littoral and sublittoral zones.[11] It burrows no more than 10 centimeters into the substrate. It sometimes lives in eelgrass beds.[11]

This species lives in many types of habitat, being found in the intertidal zone, brackish waters, & [11] estuaries. It is best maintained at a constant salinity at 30 ppt (30 g/liter) and between 15-18 °C.

Right and left valve of the same specimen:

Right valve

Right valve Left valve

Left valve

Biology and ecology

_2014.jpg.webp)

This clam may become sexually mature in its first year of life, reaching about 15 millimeters in width, especially in warmer areas such as Hawaii. In cooler areas, it begins breeding at older ages and larger sizes. In warmer regions, it spawns year-round, but only in the summer in cooler areas. The fecundity of the species increases with size, with a 40-millimeter female producing up to 2.4 million eggs.[8]

The larva, a trochophore, begins to develop a shell two days after it hatches from the egg. Within two weeks, it settles onto a hard substrate, attaches to it with a byssus, and eventually burrows into the sediment.[8] Its maximum life span is about 13[8] to 14 years.[11]

The clam filter-feeds through its siphon, taking mostly phytoplankton, with adults preferring microalgae such as diatoms. It may be an opportunistic feeder, its diet varying according to what is available in its wide range of habitat types.[8]

This species is a nutritious and attractive prey item for many kinds of predatory animals, including the green crab, moon snails, starfish, fish, ducks, shorebirds, sea otters, and raccoons.[8] It is a host species for the copepod Mytilicola orientalis, a parasite of mussels which is known as a pest in aquaculture operations.[8]

This clam has negatively impacted native ecosystems in some regions, mainly due to its ability to grow in high densities.[12] Its populations can begin filter-feeding at such rates that they can alter local food webs.[8] It can hybridize with the grooved carpet shell (Ruditapes decussatus), a phenomenon that has led to introgression.[6]

Commercial value

This species represents 25% of commercially produced mollusks in the world.[6]

This clam is considered to be a sustainable aquaculture product.[13] It is sold live or frozen.[13]

References

- MolluscaBase eds. (2022). MolluscaBase. Lajonkairia lajonkairii (Payraudeau, 1826). Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=140727 on 2023-05-30

- Cohen, A. N. 2011. Venerupis philippinarum. The Exotics Guide: Non-native Marine Species of the North American Pacific Coast. Center for Research on Aquatic Bioinvasions, Richmond, California, and San Francisco Estuary Institute, Oakland, California. Revised September 2011.

- "'Bajirak, bajirak!': Fresh sound alerting the arrival of spring".

- "Bajirak: littleneck clam".

- "바지락". nibr.co.kr.

- Cordero, D., et al. Population genetics of the Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) introduced in North America and Europe. Scientific Reports 7, Article number: 39745. 3 January 2017.

- Morris, R.H., Abbott, D.P., & Haderlie, E.C. (1980). Intertidal Invertebrates of California. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Fofonoff P. W., et al. Lajonkairia lajonkairii. National Exotic Marine and Estuarine Species Information System (NEMESIS). Accessed 22 May 2017.

- Carlton, J. T. (Ed.) (2007). The Light and Smith Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates from Central California to Oregon. University of California Press.

- Ruditapes philippinarum. Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, FAO. 2017.

- Palomares, M. L. D. and D. Pauly (Eds.) Ruditapes philippinarum. SeaLifeBase. Version February 2017.

- Study: Non-native Manila clam has established in Mission Bay, San Diego. Sea Grant California. 30 March 2015.

- Manila Clam. FishChoice.com