Mancala

Mancala (Arabic: منقلة manqalah) refers to a family of two-player turn-based strategy board games played with small stones, beans, or seeds and rows of holes or pits in the earth, a board or other playing surface. The objective is usually to capture all or some set of the opponent's pieces.

Versions of the game date back past the 3rd century and evidence suggests the game existed in Ancient Egypt. It is among the oldest known games to still be widely played today.

History

According to the Savannah African Art Museum, "archeological and historical evidence dates Mancala to the year 700 AD in East Africa. Ancient Mancala boards were found in Aksumite settlements in Matara, Eritrea, and Yeha, Ethiopia. However, the oldest Mancala boards were found in An Ghazal, Jordan in the floor of a Neolithic dwelling" as early as ~5,870 BC.[1] Evidence of the game was also uncovered in Israel in the city of Gedera in an excavated Roman bathhouse where pottery boards and rock cuts were unearthed dating back to between the 2nd and 3rd century AD. Among other early evidence of the game are fragments of a pottery board and several rock cuts found in Aksumite areas in Matara (in Eritrea) and Yeha (in Ethiopia), which are dated by archaeologists to between the 6th and 7th centuries AD;[2] the game may have been mentioned by Giyorgis of Segla in his 14th century Geʽez text Mysteries of Heaven and Earth, where he refers to a game called qarqis, a term used in Geʽez to refer to both Gebet'a (mancala) and Sant'araz (modern sent'erazh, Ethiopian chess).[3]

The games existed in especially eastern Europe. In Estonia, it was once very popular (see "Bohnenspiel"), and likewise in Bosnia (where it is called Ban-Ban and still played today), Serbia, and Greece ("Mandoli", Cyclades). Two mancala tables from the early 18th century are to be found in Weikersheim Castle in southern Germany.[4] In western Europe, it never caught on but was documented by Oxford University orientalist Thomas Hyde.[5]

The United States has a larger mancala-playing population. A traditional mancala game called Warra was still played in Louisiana in the early 20th century, and a commercial version called Kalah became popular in the 1940s. In Cape Verde, mancala is known as "ouril". It is played on the Islands and was brought to the United States by Cape Verdean immigrants. It is played to this day in Cape Verdean communities in New England.

Historians may have found evidence of Mancala in slave communities of the Americas. The game was brought to the Americas by enslaved Africans during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The game was played by enslaved Africans to foster community and develop social skills. Archeologists may have found evidence of the game Mancala played in Nashville, Tennessee at the Hermitage Plantation.[6]

Recent studies of mancala rules have given insight into the distribution of mancala. This distribution has been linked to migration routes, which may go back several hundred years.[7]

Etymology

The word mancala (Arabic: مِنْقَلَة, romanized: minqalah) is a tool noun derived from an Arabic root naqala (ن-ق-ل) meaning "to move".[8][9][10]

General gameplay

Most mancala games share a common general gameplay. Players begin by placing a certain number of seeds, prescribed for the particular game, in each of the pits on the game board. A player may count their stones to plot the game. A turn consists of removing all seeds from a pit, "sowing" the seeds (placing one in each of the following pits in sequence), and capturing based on the state of the board. The game's object is to plant the most seeds in the bank. This leads to the English phrase "count and capture" sometimes used to describe the gameplay. Although the details differ greatly, this general sequence applies to all games.

If playing in capture mode, once a player ends their turn in an empty pit on their own side, they capture the opponent's pieces directly across. Once captured, the player gets to put the seeds in their own bank. After capturing, the opponent forfeits a turn.

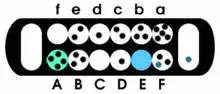

Equipment

Equipment is typically a board, constructed of various materials, with a series of holes arranged in rows, usually two or four. The materials include clay and other shapeable materials. Some games are more often played with holes dug in the earth, or carved in stone. The holes may be referred to as "depressions", "pits", or "houses". Sometimes, large holes on the ends of the board called stores, are used for holding the pieces.

Playing pieces are seeds, beans, stones, cowry shells, half-marbles or other small undifferentiated counters that are placed in and transferred about the holes during play.

Board configurations vary among different games but also within variations of a given game; for example Endodoi is played on boards from 2×6 to 2×10. The largest is Tchouba (Mozambique) with a board of 160 (4×40) holes requiring 320 seeds, and En Gehé (Tanzania), played on longer rows with up to 50 pits (a total of 2×50=100) and using 400 seeds. The most minimalistic variants are Nano-Wari and Micro-Wari, created by the Bulgarian ethnologue Assia Popova. The Nano-Wari board has eight seeds in just two pits; Micro-Wari has a total of four seeds in four pits.

With a two-rank board, players usually are considered to control their respective sides of the board, although moves often are made into the opponent's side. With a four-rank board, players control an inner row and an outer row, and a player's seeds will remain in these closest two rows unless the opponent captures them.

Objective

The objective of most two- and three-row mancala games is to capture more stones than the opponent; in four-row games, one usually seeks to leave the opponent with no legal move or sometimes to capture all counters in their front row.

At the beginning of a player's turn, they select a hole with seeds that will be sown around the board. This selection is often limited to holes on the current player's side of the board, as well as holes with a certain minimum number of seeds.

In a process known as sowing, all the seeds from a hole are dropped one by one into subsequent holes in a motion wrapping around the board. Sowing is an apt name for this activity, since not only are many games traditionally played with seeds but placing seeds one at a time in different holes reflects the physical act of sowing. If the sowing action stops after dropping the last seed, the game is considered a single lap game.

Multiple laps or relay sowing is a frequent feature of mancala games, although not universal. When relay sowing, if the last seed during sowing lands in an occupied hole, all the contents of that hole, including the last sown seed, are immediately re-sown from the hole. The process usually will continue until sowing ends in an empty hole. Another common way to receive "multiple laps" is when the final seed sown lands in your designated hole.

Many games from the Indian subcontinent use pussakanawa laps. These are like standard multi-laps, but instead of continuing the movement with the contents of the last hole filled, a player continues with the next hole. A pussakanawa lap move will then end when a lap ends just before an empty hole.

If a player ends their stone with a point move they get a "free turn".

Capturing

Depending on the last hole sown in a lap, a player may capture stones from the board. The exact requirements for capture, as well as what is done with captured stones, vary considerably among games. Typically, a capture requires sowing to end in a hole with a certain number of stones, ending across the board from stones in specific configurations or landing in an empty hole adjacent to an opponent's hole that contains one or more pieces.

Another common way of capturing is to capture the stones that reach a certain number of seeds at any moment.

Also, several games include the notion of capturing holes, and thus all seeds sown on a captured hole belong at the end of the game to the player who captured it.

Names and variants

The name is a classification or type of game, rather than any specific game. Some of the most popular mancala games (concerning distribution area, the numbers of players and tournaments, and publications) are:

- Bao – played in most of East Africa including Kenya, Tanzania, Comoros, Madagascar, Malawi, as well as some areas of DR Congo, and Burundi.[11]

- Gebeta (Tigrinya: ገበጣ) – played in Ethiopia and Eritrea (especially in Tigray).

- Kalah – North American variation, the most popular variant in the Western world.

- Omweso (mweso) – played in Uganda, some players and tournaments also in the UK.

- Oware (awalé, awélé, awari) – Ashanti, but played world-wide including Europe (England, France, Catalonia, Portugal), where it is mostly played (but not exclusively) by expatriates; close variants in West Africa (e.g., Ayo by Yorubas (Nigeria), Ouri (Cape Verde)) and Warri in the Caribbean.[12][13][14]

- Pallanguzhi – played in Tamil Nadu, India.

- Songo – played in Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon, also among expatriates in France.

- Sungka – Popular variants are known as Congklak (a.k.a. congkak, congka, tjongklak, jongklak) and Dakon (or dhakon) – played in Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines and Brunei; boards are often sold in fairtrade shops in Germany and other European countries.

- Toguz korgool or Toguz kumalak – played in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, tournaments also in Europe.

Although more than 800 names of traditional mancala games are known, some names denote the same game, while others are used for more than one game. Almost 200 modern invented versions have also been described.

Psychology

Like other board games, mancala games have led to psychological studies. Retschitzki has studied the cognitive processes used by awalé players.[15] Some of Restchitzki's results on memory and problem solving have recently been simulated by Fernand Gobet with the CHREST computer model.[16] De Voogt has studied the psychology of Bao playing.[17]

Competition

Several groups of Mancala games have their own tournaments. A medley tournament including at least two modalities has been part of the Mind Sports Olympiad, including in the in-person event and the online Grand Prix.[18]

Mancala at the Mind Sports Olympiad

| Games | Gold | Silver | Bronze |

|---|---|---|---|

| London 2015 |

Yoon-Ji Bae |

Yeon-Woo Choi |

Hyo-Seok Lee |

| Online Grand Prix 2023 |

Pavel Noga |

Maurizio De Leo |

David Alatorre López |

References

- "Mancala". Savannah African Art Museum. Savannah African Art Museum. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- Natsoulas (1995). "The Game of Mancala with Reference to Commonalities among the Peoples of Ethiopia and in Comparison to Other African Peoples: Rules and Strategies". Northeast African Studies. 2 (2): 7–24. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- Pankhurst, Richard (2005). "Gäbäṭa". In Uhlig, Siegbert von (ed.). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D–Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 598. ISBN 3-447-05238-4.

- "Afrostyle Magazine". afrostylemag.com. Retrieved 2018-01-17.

- Thomas Hyde, De ludis orientalibus [Of Eastern Games, 2 vols.] (Oxford University Press, 1694). https://www.worldcat.org/title/de-ludis-orientalibus-libri-duo-quorum-prior-est-duabus-partibus-viz-1-historia-shahiludii-latine-deinde-2-historia-shahiludii-heb-lat-per-tres-judaeos-liber-posterior-continet-historiam-reliquorum-ludorum-orientis/oclc/174276156?referer=di&ht=edition Reference to Hyde's discussion of mancala and other games in Vesna Biki�c and Jasna Vukovi�c, "Board Games Reconsidered: Mancala in the Balkans", International Journal of the History of Sport 27/5 (Mar. 2010): 798–819. Download citation https://doi.org/10.1080/09523361003625857

- Christiano (2010). "Gaming among Enslaved Africans in the Americas, and its Uses in Navigating Social Interactions". Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects /College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences: 8–12. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- Peek, Philip M.; Yankah, Kwesi (March 7, 2004). African Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135948733 – via Google Books.

- "English words from Arabic". zompist. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- "Mancala". Lexbook. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- Cannon, Garland; Kaye, Alan S. (1994). The Arabic contributions to the English language : an historical dictionary. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 81. ISBN 3-447-03491-2. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- Hyde (1694), pp. 226-232

- "Oware". BoardGameGeek.

- "Oware – Played all over the world". oware.org.

- "African Games of Strategy: A Teaching Manual". African Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. February 7, 1982 – via Google Books.

- Retschitzki, J. (1990). Stratégies des Joueurs d'Awélé. Paris: Édition L'Harmattan. ISBN 2738406173.

- Gobet, F. (2009). "Using a cognitive architecture for addressing the question of cognitive universals in cross-cultural psychology: The example of awalé". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 40 (4): 627–648. doi:10.1177/0022022109335186. S2CID 145345443.

- Voogt, A. J. de (1995). Limits of the Mind: Towards a Characterisation of Bao Mastership. Leiden: CNWS Publications.

- "Results for Mancala". Mind Sports Olympiad. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

Further reading

- Culin, Stewart (1896). Mancala, the National Game of Africa. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Erickson, Jeff (1998). "Sowing Games". Games of No Chance. Cambridge University Press.

- Laurence Russ (1984). Mancala Games. Reference Publications. ISBN 978-0-917256-19-6.

- Russ, Larry (2000). The Complete Mancala Games Book. New York: Marlowe.

- Townshend, Philip (1979). "African Mankala in Anthropological Perspective". Current Anthropology. 20 (4): 794–796. doi:10.1086/202380. JSTOR 2741688. S2CID 143060530.

- Deledicq, A. & A. Popova (1977). Wari et solo. Le jeu de calcul Africain. Paris: Cedic.

- Murray, H.J.R. (1952). A History of Board-Games other than Chess. Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

- Townshend, P. (1982). "Bao (mankala): the Swahili ethic in African idiom". Paideuma. 28: 75–191. JSTOR 41409882.

- Voogt, A.J. de (1997). Mancala Board Games. British Museum Press: London.