Manual handling of loads

Manual handling of loads (MHL) or manual material handling (MMH) involves the use of the human body to lift, lower, carry or transfer loads. The average person is exposed to manual lifting of loads in the work place, in recreational atmospheres, and even in the home. To properly protect one from injuring themselves, it can help to understand general body mechanics.[1]

Hazards and injuries

Manual handling of materials can be found in any workplace from offices to heavy industrial and manufacturing facilities. Often times, manual material handling entails tasks such as lifting, climbing, pushing, pulling, and pivoting, all of which pose the risk of injury to the back and other skeletal systems which can often lead to musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). Musculoskeletal disorders can be defined as often involving strains and sprains to the lower back, shoulders, and upper limbs.[2] According to a U.S. Department of Labor study published in 1990, back injuries accounted for approximately 20% of all injuries in the workplace which accounted for almost 25% of the total workers compensation payouts.[3]

To better understand the potential injuries of manual handling of materials, we must first understand the underlying conditions which can cause the injuries. When an injury occurs from manual handling of materials, it often is a result of one of the following underlying condition(s).

- Awkward posture: Bending or twisting

- Repetitive motions: Frequency of a task

- Forceful exertions: Carrying or lifting heavy loads

- Pressure points: The load applying pressure to select areas on the body only

- Static postures: Staying in the same position for extended periods of time[2]

Although musculoskeletal disorder can develop overtime, when manual handling of materials, they can also occur after only one activity. Some of the common injuries associated with manual handling of loads include but are not limited to:

- Sprains and strains of muscles, ligaments, and tendons

- Back injuries

- Bone injuries

- Nerve injuries

- Tissue injuries

- Acute and Chronic Pain[4]

In addition to the injuries listed above, the worker can be exposed to soreness, bruises, cuts, punctures, crushing, Remember your health comes first, it is temporary so make good use of it.

Commonly affected industries and workforces

Although employee's can be exposed to manual handling of materials in any industry or workplace there are workplaces that are more susceptible to hazards of manual material handling. These industries include but are not limited to:

- Warehousing

- Manufacturing facilities

- Factories

- Construction sites

- Hospitals

- Nursing home and retirement facilities

- Emergency services (fire, medical, police)

- Farms/ranches[5]

Evaluation or assessment tools

There are multiple tools which can be used to assess the manual handling of material. Some of the most common methods are discussed below in no particular order.

NIOSH lifting equation

The U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the United States Department of Health and Human Services. NIOSH first published the NIOSH lifting equation in 1991 and went into effect July 1994. NIOSH made changes to the NIOSH lifting equation manual in 2021 which included updated graphics and tables and identified errors were corrected.[6]

The NIOSH lifting equation is a tool (now application ) that can be used by health and safety professionals to assess employees who are exposed to manual lifting or handling of materials.[7] The NIOSH lifting equation is a mathematical calculation which calculates the Recommended Weight Limit (RWL) using a series of tables, variables, and constants. The equation for the NIOSH lifting equation is shown below

where:

- LC is a load constant of 23 kg (~51 lb)

- HM is the horizontal multiplier

- VM is the vertical multiplier

- DM is the distance multiplier

- AM is the asymmetric multiplier

- FM is the frequency multiplier

- CM is the coupling multiplier

Using the RWL, you can also find the lifting index (LI) using the following equation:

The lifting index can be used to identify the stresses that each lift will expose the employees. The general understanding is that as the LI increased, the higher risk the worker is exposed to. As the LI decreases, the worker is less likely to develop back related injuries. Ideally, any lifting tasks should have a lifting index of 1.0 or less.[3]

The NIOSH lifting Equation does have some limitations which include:

- Only using one hand for lifting/lowering

- Lifting or lowering for over 8 hours

- Lifting or lowering while in the seated or kneeling position

- Lifting or lowering in restricted areas (where full range of motion cannot be achieved

- Lifting or lowering unstable objects

- Lifting or lowering while carrying, pushing, or pulling.

- Lifting or lowering using devices such as wheelbarrows or shovels

- Lifting or lowering with high speed motion

- Lifting or lowering on unstable floors

- Lifting or lowering in extreme heat, cold, or humidity.[8]

The NIOSH Revised Lifting Equation Manual can be found on the CDC's website or by clicking here.

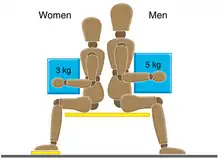

Liberty Mutual tables

Liberty Mutual Insurance has studied tasks related to manual materials handling, resulting in a comprehensive set of tables which predicts the percentages of both the male and female population that can move the weight of the object. The Liberty Mutual Risk Control Team recommends that tasks should be designed so that 75% or more of the female work force population can safely complete the task.

Key components that first must be collected before using the Liberty Mutual tables are:

- Total weight of object

- Hand distance (distance away from the body)

- Initial hand height (hand height at start of lift)

- Final hand height (hand height at end of lift)

- Frequency (how often is this task completed)[9]

The complete Liberty Mutual tables and their guidelines can be found at their website. Liberty Mutual Insurance also has provided calculators that will manually calculate the percentage for both the male and female populations. If the percentage is less than 75% for the female population, a redesign of the lifting plan should be created so that 75% or more of the female population can conduct the materials handling. The link to the calculator can be found here.

Rapid Entire Body Assessment

The Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) is a tool developed by Dr. Sue Hignett and Dr. Lynn McAtamney which was published July 1998 in the Applied Ergonomics journal. This measurement device was designed to be a tool that health and safety professionals could use in the field to assess posture techniques in the workplace. Rather than heavily reliant on the weight of the object being lifted, Dr. Hignett and Dr. McAtamney developed this tool based on the posture of the employee lifting the weight. Using a series of mathematical calculations and a series of tables, each activity is assigned a REBA score. To calculate the REBA score, the tool separates the body parts into the two groups group A and group B. The body parts assigned to Group A are:

- Neck

- Trunk

The body parts assigned to group B are:

- Upper arms

- Lower arms

- Wrists

Using the score of each body part posture in group A, locate the score in table A to assign a group A posture score. This score is then added to the Load or force. This sum is the score A.

Using the score of each body part posture in group B, locate the score in table B to assign a group B posture score. This score is then added to the coupling score. This sum is the score B.

Using score A and score B, the correct score C is assigned using table C. The score C is then added to the activity score. This sum is the REBA score. The REBA score is a numerical value between 0 and 4. A REBA score of 0 has a negligible risk level, while a REBA score 4 has a very high-risk level. The REBA score can also provide how quickly action needs to be taken for each REBA score.[10]

Rapid Upper Limb Assessment

The Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA) is a tool developed by Dr. Lynn McAtamney and Professor E. Nigel Corlett which was published in 1993 in the Applied Ergonomics journal.[11] Very similarly to the REBA tool, this tool was designed so that health and safety professionals could assess lifting in the field. The tool is mainly focused on posture. Using a series of mathematical calculations and a series of tables, each activity is assigned a RULA score. To calculate the RULA score, the tool separates the body parts into the two groups group A and group B. The body parts assigned to group A are:

- Upper arm

- Lower arm

- Wrist position

The body parts assigned to group B are:

- Neck position

- Trunk position

- Legs

Using the score of each body part posture in group A, locate the score in table A to assign a group A posture score. This score is then added to the muscle use score and the force/load score which assigns the wrist and arm Score.

Using the score of each body part posture in group B, locate the score in table B to assign a group B posture score. This score is then added to the muscle use score and force/load score which equals the neck, trunk, leg score.

Using table C, locate the wrist/arm score in the Y-axis and the neck, trunk, leg score on the X-axis to determine the RULA score. The RULA score is a numerical value between 1 and 7. If the RULA score returns a 1 or 2, the posture is acceptable but if the RULA score is a 7, changes are needed.[11]

Equipment to reduce risk of injury

To help mitigate the risk of injury from manual material handling there are devices which can be used to help mitigate some of the risk of manual material handling.

Exoskeletons

Exoskeletons are devices which can be used to supplement the human body when completing tasks which require repetitive motions or using strength to complete a job. Exoskeletons can be powered or passive. Powered exoskeletons are powered using a battery which will supplement the strength needed for lifting materials. Passive exoskeletons are non-powered devices that are focused on a specific muscle group.[12]

Overhead cranes

Overhead cranes or workstation cranes can drastically decrease the exposure to workers for lifting and moving heavy objects. These devices can assist the worker by mechanically lifting, lowering, turning, or moving a heavy object to a different location.[13]

Handles and grip aids

When lifting heavy materials, the grip matters. By using handles, the grip could drastically change the posture of the lift. It can also reduce pressure points while lifting.

Forklifts

Forklifts are powered vehicles (gas, diesel, electric) that are often used in facilities to move heavy items. The truck can pick up significantly heavier objects compared to the human and move it to a new location. Since the forks can be adjusted, the height of the lift can also be adjusted so that employees can lift in a more neutral position. The use of forklifts can eliminate or reduce some exposures of manual material handling.

Pallet jacks

Pallet jacks are a great tool that can assist in moving heavy objects. Pallet jacks can be both powered and manual, so it is important to understand the weight being moved. If the weight exceeds the amount a person can easily push/pull, alternative means should be considered such as a forklift or a powered pallet jack.

Adjustable workstations

The workstation height is critical to posture and preferred ergonomic principles. If the workstation is properly adjusted, it can prevent bending over and exposing the worker to awkward posture. Having an adjustable workstation can also allow the employee to adjust the height based on their height so that they can perform their work using good ergonomic principle.

Ways to reduce risk of injury

The safest way to manual materials handling is to eliminate any manual handling of materials using the hierarchy of control. There will be times where elimination is not an option. Below are some ways to reduce the risk of injury if manual materials handling is present.

Stretch and flex programs

Stretch and flex programs are designed to help reduce workplace injuries. Using a stretch and flex program allows the worker to properly warm up before exerting lots of energy in their normal workdays. When properly stretched and warming up, the workers heartrate increases which in returns blood flow, nutrients, and oxygen to muscle groups. When the body is properly warmed up, muscle injuries are less likely to occur.[14] Physical and occupational therapists can be contracted to help develop a Stretch and Flex Program that is best suited for the work taking place.[15]

Rest and recovery

Just like any muscle use, it is critical to provide the muscles proper rest to allow for them to recover properly. One key mitigation effort would be proper rest. Getting a good nights sleep is critical to help employees reduce workplace injuries from manual material handling. Throughout the day, employees should incorporate breaks to allow for their muscles to rest and so that the employees can rehydrate and rest to prevent fatigue.[15]

Another principle that employers can use is a job rotation. These tasks will only expose the workers to fatigue in certain muscles groups instead of repetitively working the same muscle group. Allowing employees to rotate jobs will allow for longer rest and recovery and can potentially lessen the exposure to manual handling of materials.[15]

Safe manual materials handling techniques

Using proper ergonomic techniques while manual handling of materials will help reduce the likelihood of injury. Below are a few good practices to follow while manual handling of materials.

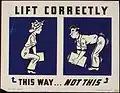

Lifting technique: Face forwards, good grip, neutral spine, feet hip width and not parallel

Lifting technique: Face forwards, good grip, neutral spine, feet hip width and not parallel Correct Pick-up Avoid Hernia (Office of emergency management 1940s)

Correct Pick-up Avoid Hernia (Office of emergency management 1940s) Lift correctly. This way... Not this (Office of emergency management, 1940s)

Lift correctly. This way... Not this (Office of emergency management, 1940s)

Safe lifting techniques

- Know the weight of the load

- Make sure ones footing is on stable and non-slip surfaces

- Bend the knees and keep the back straight

- Grab the load with a safe grip

- Lift with legs keeping the load within the "power zone"

- Lower the load using your knees and keeping the back straight

Climbing

When climbing with a load, safe material handling includes maintaining contact with the ladder or stairs at three points (two hands and a foot or both feet and a hand). Bulky loads would require a second person or a mechanical device to assist.

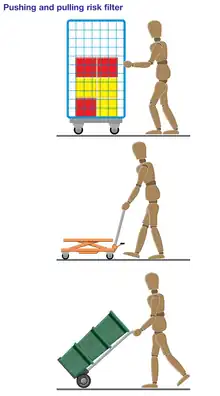

Pushing and pulling

Manual material handling may require pushing or pulling. Pushing is generally easier on the back than pulling. It is important to use both the arms and legs to provide the leverage to start the push.[16]

Pivoting

When moving containers, handlers are safer when pivoting their shoulders, hips and feet with the load in front at all times rather than twisting only the torso.

Two people lifting

When handling heavy materials that exceed an individual's lifting capacity, experts suggest working with a partner to minimize the risk of injury. Two people lifting or carrying the load not only distributes the weight evenly but also utilizes their natural lifting capacity, reducing the chances of strains or sprains. Proper communication between partners is necessary for coordination during the lift, ensuring the safety of both the participants, the goods being carried, and the surrounding environment.

Legislation

In the UK, all organisations have a duty to protect employees from injury from manual handling activities and this duty is outlined in the Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 (MHOR) as amended.[17]

The regulations define manual handling as "[...] any transporting or supporting of a load (including the lifting, putting down, pushing, pulling, carrying or moving thereof) by hand or bodily force". The load can be an object, person or animal.[17]

In the United States, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is the governing body which regulates workplace safety. OSHA does not have a standard which sets a maximum allowable weight that employers must follow.[18] However, manual materials handling may fall under Section 5(a) which is often referred to as the General Duty Clause. The OSHA general duty clause states “Each employer—shall furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees…"[18]

See also

References

- Tammana, Aditya; McKay, Cody; Cain, Stephen M.; Davidson, Steven P.; Vitali, Rachel V.; Ojeda, Lauro; Stirling, Leia; Perkins, Noel C. (2018-07-01). "Load-embedded inertial measurement unit reveals lifting performance". Applied Ergonomics. 70: 68–76. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2018.01.014. ISSN 0003-6870. PMID 29866328. S2CID 46936880.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (2007). "Ergonomic Guidelines for Manual Material Handling" (PDF).

- "Applications manual for the revised NIOSH lifting equation". 1994-01-01. doi:10.26616/nioshpub94110.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Lifting, pushing and pulling (manual tasks) | Safe Work Australia". www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- "Hazards and Risks Associated with Manual Handling in the Workplace" (PDF).

- Nelson(1), Wickes(2), English(3), Gary S (1), Henry (2), Jason T. (3) (1994). "Manual Lifting: The Revised NIOSH Lifting Equation for Evaluating Acceptable Weights for Manual Lifting" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "A Step-by-Step Guide to Using the NIOSH Lifting Equation for Single Tasks". ErgoPlus. 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- "Applications manual for the revised NIOSH lifting equation" (PDF). 1994-01-01. doi:10.26616/nioshpub94110.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Manual Handling Guidelines:Using Liberty Mutual Tables" (PDF). 2017.

- Hignett, Sue; McAtamney, Lynn (April 2000). "Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA)". Applied Ergonomics. 31 (2): 201–205. doi:10.1016/S0003-6870(99)00039-3. PMID 10711982. S2CID 32267723.

- "CUergo: RULA". ergo.human.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- "Exoskeletons and Ergonomics - What You Need to Know". Sustainable Ergonomics Systems. 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- "Handle Workpieces More Ergonomically With Workstation Cranes". Overhead Lifting. 2021-03-10. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- "Ergonomic Stretch & Flex Programs for the Workplace | ergo-ology". 2019-10-30. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- "Ergonomic Breaks, Rest Periods, and Stretches". content.statefundca.com. 21 July 2020. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- "Injury Prevention Tip: Train your employees to prevent overexertion injuries from pushing and pulling tasks". ErgoPlus. 2011-11-02. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- Health and Safety Executive, Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 (as amended) (MHOR), accessed 17 October 2020

- "OSHA procedures for safe weight limits when manually lifting | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

External links

- Ergonomic Guidelines for Manual Material Handling, from Cal/OSHA

- Hazards and risks associated with manual handling of loads in the workplace - European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA)

- Code of practice - Manual tasks - Western Australia

- Manual Handling pathfinder

- Development of a screening method for manual handling by RA Graveling and others, Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/92/08

- Evaluation of the Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 and Guidance by KM Tesh and others. Health and Safety Executive, Contract Research Report No. 152/1997

- The principles of good manual handling: achieving a consensus by RA Graveling and others, Health and Safety Executive Research Report No. 097/2003