Ellalan

Ellalan (Tamil: எல்லாளன், romanized: Ellāḷaṉ; Sinhala: එළාර, romanized: Eḷāra) was a member of the Tamil Chola dynasty in Southern India, also known as "Manu Needhi Cholan", who upon capturing the throne became king of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, in present-day Sri Lanka, from 205 BCE to 161 BCE.[3]

| Ellalan | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Statue of Ellāḷaṉ in the premises of Madras High Court in Chennai | |

| King of Anuradhapura | |

| Reign | c. 205 – c. 161 BCE |

| Predecessor | Asela |

| Successor | Dutugamunu |

| Born | 235 BCE |

| Died | 161 BCE |

| Issue | Veedhividangan[1] Princess Shardha |

| Dynasty | Chola Dynasty |

| Religion | Hinduism[2] |

| Chola kings and emperors |

|---|

| Interregnum (c. 200 – c. 848) |

| Related |

Ellalan is traditionally presented as being a just king even by the "'Sinhalese'".[4] The Mahavamsa states that he ruled 'with even justice toward friend and foe, on occasions of disputes at law,[5] and elaborates how he even ordered the execution of his son for killing a calf under his chariot wheels.

Ellalan is a peculiar figure in the history of Sri Lanka and one with particular resonance given the past ethnic strife in the country. Although he was an invader, he is often regarded as one of Sri Lanka's wisest and most just monarchs, as highlighted in the ancient Sinhalese Pali chronicle, the Mahavamsa.

According to the chronicle, even Ellalan's nemesis Dutugamunu had a great respect for him, and ordered a monument be built where Ellalan was cremated after dying in battle. The Dakkhina Stupa was believed to be the tomb of Ellalan. Often referred to as 'the Just King', the Tamil name Ellāḷaṉ means 'the one who rules the boundary".

Birth and early life

Ellalan is described in the Mahavamsa as being "A Damila of noble descent . . . from the Chola-country";[5] In that work, he is mentioned as Elara. Little is known of his early life. Around 205 BCE, Ellalan mounted an invasion of the Rajarata based in Anuradhapura in northern Sri Lanka and defeated the forces of king Asela of Anuradhapura, establishing himself as sole ruler of Rajarata. Ellalan's territory is said to have been to the north of the Mahaweli River[6]

He has been mentioned in the Silappatikaram and Periya Puranam.[7] His name has since then been used as a metaphor for fairness and justice in Tamil literature. His capital was Thiruvarur.

Defeat and death

Despite Ellalan's famously even-handed rule, resistance to him coalesced around the figure of Dutugamunu, a young Sinhalese prince from the kingdom of Mahagama. Towards the end of Ellalan's reign, Dutugamunu had strengthened his position in the south by defeating his own brother, Saddha Tissa, who challenged him. Confrontation between the two monarchs was inevitable and the last years of Ellalan's reign were consumed by the war between the two. Ellalan was near seventy years when the battle with the young Dutugamunu took place.[8]

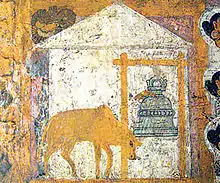

The Mahavamsa contains a fairly detailed account of sieges and battles that took place during the conflict.[4] Particularly interesting is the extensive use of war elephants and of flaming pitch in the battles. Ellalan's own war elephant is said to have been Maha Pabbatha, or 'Big Rock' and the Dutugamunu's own being 'Kandula'.[9]

The climactic battle is said to have occurred as Dutugamunu drew close to Anuradhapura. On the night before, both King Ellalan and prince Dutugamunu are said to have conferred with their counsellors. The next day both kings rode forwards on war elephants, Ellalan "in full armour . . . with chariots, soldiers and beasts for riders". Dutugamunu's forces are said to have routed those of Ellalan and that "the water in the tank there was dyed red with the blood of the slain'. Dutugamunu, declaring that 'none shall kill Ellalan but myself', closed on him at the south gate of Anuradhapura, where the two engaged in an elephant-back duel and the aged king was finally felled by one of Dutugamunu's darts.[8]

Following his death, Dutugamunu ordered that Ellāḷaṉ be cremated where he had fallen, and had a monument constructed over the place. The Mahavamsa mentions that 'even to this day the princes of Lanka, when they draw near to this place, are wont to silence their music'. The Dakkhina Stupa was until the 19th century believed to have been the tomb of Ellalan and was called Elara Sohona, but was renamed later on by the Sri Lankan Department of Archaeology.[10][11] The identification and reclassification is considered controversial.[12]

Influence

The Mahavamsa contains numerous references to the loyal troops of the Chola empire and portrays them as a powerful force. They held various positions including taking custody of temples during the period of Parakramabahu I and Vijayabahu I of Polonnaruwa.[13][14] There were instances when the Sinhalese kings tried to employ them as mercenaries by renaming a section of the most hardcore fighters as Mahatantra. According to historian Burton Stein, when these troops were directed against the Chola empire, they rebelled and were suppressed and decommissioned. But they continued to exist in a passive state by taking up various jobs for livelihood.[15] The Valanjayara, a sub-section of the Velaikkara troops, were one such community, who in the course of time became traders. They were so powerful that the shrine of the tooth-relic was entrusted to their care.[16][17] When the Velaikkara troops took custody of the tooth-relic shrine, they called it as Mūnrukai-tiruvēlaikkāran daladāy perumpalli.[18] There are also multiple epigraphic records of the Velaikkara troops. It is their inscriptions, for example the one in Polunnaruwa, that are actually used to fix the length of the reign of Sinhalese kings; in this case, Vijayabahu I (55 years).[19]

The Sri Lanka Navy Northern Naval Command base in Karainagar, Jaffna is named the SLNS Elara[20]

The Legend of Manu Needhi Cholan

Ellalan received the title "Manu Needhi Cholan" (the Chola who follows justice) because he executed his own son to provide justice to a cow. Legend has it that the king hung a giant bell in front of his courtroom for anyone needing justice to ring. One day, he came out on hearing the ringing of the bell by a cow. Upon enquiry, he found that the calf of that cow had been killed under the wheels of his son's chariot. In order to provide justice to the cow, Ellalan killed his own son, Veedhividangan, under the chariot as his own punishment i.e. Ellalan made himself suffer as much as the cow.[1] Impressed by the justice of the king, Lord Shiva blessed him and brought back the calf and his son alive. He has been mentioned in the Silappatikaram and Periya Puranam.[7] His name has since then been used as a metaphor for fairness and justice in Tamil literature. His capital was Thiruvarur.

The Mahavamsa also states that when he was riding his cart he accidentally hit a Chetiya. After that he ordered his ministers to kill him but the ministers replied that Buddha would not approve such an act. The king asked what he should do to rectify the damage and they said that repairing the structure would be enough which is what he did.[21]

Chronicles such as the Yalpana Vaipava Malai and stone inscriptions like Konesar Kalvettu recount that Kulakkottan, an early Chola king and descendant of Manu Needhi Cholan, was the restorer of the ruined Koneswaram temple and tank at Trincomalee in 438, the Munneswaram temple of the west coast, and as the royal who settled ancient Vanniyars in the east of the island Eelam.[22][23]

References

- "From the annals of history". The Hindu. India. 25 June 2010.

- Paramu Pusparaṭṇam (2002). Ancient Coins of Sri Lankan Tamil Rulers. p. 92.

The Mahāvamsa ( XXI : 15-34 ) talks high of the just and righteous regime of Ellālan . He followed the Hindu religion but did not persecute the Buddhists.

- Allen, C. (2017). Coromandel: A Personal History of South India. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4087-0540-7. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

A later chapter of the 'Great Chronicle' describes how the Chola prince Elara (Ellalan) of Thiruvarur invaded and captured the throne of Lanka in about 205 BCE but was later killed in battle by the Sinhala prince Dutugamunu in about 161

- "Chapter XXV". lakdiva.org.

- "Chapter XXI". lakdiva.org.

- Sastri, Nilakanta KA (1955). The Colas (2nd ed.). Chennai: University of Madras. p. 24.

- "Tiruvarur in religious history of Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 16 July 2010. Archived from the original on 18 July 2010.

- Obeyesekere, Gananath (27 November 1990). The Work of Culture: Symbolic Transformation in Psychoanalysis and Anthropology. University of Chicago Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780226615981.

- "War Against King Elara". mahavamsa.org. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Archaeological Department Centenary (1890-1990): History of the Department of Archaeology. Commissioner of Archaeology. 1990. p. 171.

- McGilvray, Dennis B. (1993). Reviewed Work: The Presence of the Past: Chronicles, Politics, and Culture in Sinhala Life.by Steven Kemper. The University of Colorado Boulder: The Journal of Asian Studies. p. 1058. JSTOR 2059412.

- Indrapala, K. The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 368

- The tooth relic and the crown, page 59

- Epigraphia Zeylanica: being lithic and other inscriptions of Ceylon, Volume 2, page 250

- Journal of Tamil studies, Issues 31-32, page 60

- The Ceylon historical journal, Volumes 1-2, page 197

- Culavamsa: Being the More Recent Part of Mahavamsa

- Early South Indian temple architecture: study of Tiruvāliśvaram inscriptions, page 93

- "SLNS Elara conducts Medical and Dental Clinic at Karainagar". Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- "King Elara (204 BC – 164 BC)". mahavamsa.org. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (1994). "Tamils and the meaning of history". Contemporary South Asia. Routledge. 3 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1080/09584939408719724.

- Schalk, Peter (2002). "Buddhism Among Tamils in Pre-colonial Tamilakam and Ilam: Prologue. The Pre-Pallava and the Pallava period". Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Uppsala University. 19–20: 159, 503.

The Tamil stone inscription Konesar Kalvettu details King Kulakottan's involvement in the restoration of Koneswaram temple in 438 A.D. (Pillay, K., Pillay, K. (1963). South India and Ceylon);

External links

- Tamil Nadu History

- Sri Lankan history

- The Tomb of Elara at Anuradhapura

- එළාර රජුගේ හිතුවක්කාර නීතිය Archived 8 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine (in Sinhala)

- எல்லாளன் சமாதியும் வரலாற்று மோசடியும் (in Tamil)