Mara the Lioness

Mara the Lioness (1965–1974) was an animal actor who appeared as Elsa in the 1966 movie Born Free, based on the true story of Elsa the Lioness raised by George and Joy Adamson.

Mara was born in the wild in 1965, a premature cub abandoned by her mother during a violent rain storm. She was found lying on sodden ground, caked in mud on the plains of Masailand by Samwel, an African game scout and Larry Wateridge. Sick with hunger and in a semi coma, she was taken to a nearby coffee plantation in Kenya owned by British couple Irene and Douglas Grindlay.[1]

Irene Grindlay took it upon herself to nurse the ailing cub back to health. Initially Mara was to stay only a few days but she soon became a permanent fixture, hand reared and fully domesticated. As she grew larger however it became increasingly clear that she would need to be relocated.[2]

The most obvious choice was the local animal orphanage at the entrance to the Nairobi National Park. Opened in September 1963 as a refuge for orphaned or sick wild animals, the park initially held less than thirty animals, with Ugas (who also starred in the movie Born Free) the only lion. By 1965 the park held 117 orphans of 36 species including lion, leopard, cheetahs, african buffalo, camels, hyena, jackal and wild dogs.[3]

It took many months for Mara to settle into her new home where she was affectionately known as the "friendly lioness".[4] The Grindlays, as self-appointed guardians, remained in frequent contact.

Fame

Mara had only been in the Animal Orphanage for about six months when the Born Free film crew arrived. They were looking for lionesses to play the part of Elsa and decided that Mara would make an ideal adult Elsa. Seventeen lionesses were selected from across Africa and used to portray this famous big cat; their ages ranging from a few weeks to several years old. In total there were twenty-one lions and lionesses used during filming, with Mara the primary animal actor.[2]

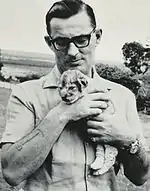

Although Mara's size and weight required delicate handling on set, she was placid and easily directed. The Grindlays were regulars on set but were careful never to attend when Mara was filming because Mara had a tendency to stray towards them. Her affection for the Grindlays and theirs for her never waned.[5]

Life after Born Free

Once filming had completed, Mara returned to the Animal Orphanage, however the Board of Trustees of the Kenya National Parks became concerned regarding in the increase in the number of adoptees. They requested that Mara, Ugas and three younger lionesses be relocated to Whipsnade Park. The Grindlays, who maintained responsibility for Mara, eventually agreed to release Mara into the care of Whipsnade.

While waiting to go to Whipsnade, reports surfaced that Ugas, Mara and three other lionesses were to be rehabilitated by George and Joy Adamson. The proposed experiment was heavily protested.[6]

The Grindlays were opposed to the idea because Mara's behaviour was that of a domesticated dog. Along with animal lovers, naturalists and experienced game wardens, they held the belief that integration back into the wild would harm Mara, rather than benefit. Mara did not fear man and indeed went out of her way to approach and play. This posed an enormous risk to her safety.

In addition, release into the wild would place Mara and the other lionesses at risk of contracting Babesia. Domesticated animals have no resistance to the fatal disease, a fact which George and Joy Adamson knew. Their lion Elsa had died of the same disease not less than two years earlier when they had attempted to release her back into the wild.[7]

Eventually only Ugas was released into the Meru Game Reserve. It was decided that Mara was too tame and she and the other lionesses should be relocated to Whipsnade Park. Just prior to her departure Mara gave birth to male and female twin cubs, sired by Ugas during the filming of Born Free.

In 1966, Irene Grindlay wrote a book titled Velvet Paws which detailed the life of Mara up to and including her appearance in the movie Born Free.

"We have no reason to reproach ourselves. We are quite convinced that we did the right thing in opposing her release and that for many years to come in Whipsnade Park she will be well-fed, contented and ... safe." (Irene Grindlay, 1966)

It is not known how long Mara resided at Whipsnade Park. The life span of a lion in the wild is approximately 12 years, while those in captivity have been known to live for more than 20. If Mara was fortunate she would have died in the early to mid eighties. Mara lived the rest of her life at Whipsnade Park, she died in 1974.

Films

- The Lions Are Free is the real life continuation of the award-winning movie classic Born Free. This film tells in a most personal and touching way about what happened to the lions that were in Born Free. Bill Travers who starred in Born Free, travels to a remote area in Kenya East Africa to visit conservationist George Adamson and several of his lion friends. There are some scenes of George Adamson and Bill Travers interacting with lions who are living free. James Hill who directed Born Free produced this film along with Bill Travers. In November 2006, this film and the film Christian The Lion at World's End were both released on DVD.

- Mara is also a lion cub's name in the Disneynature 2011 documentary film African Cats.

References

- Denis, Michaela 'Forward' in Grindlay, Irene. Velvet paws: the story of Mara, the young lioness. London: Robert Hale (1966) p. 10

- Grindlay, Irene. Velvet paws: the story of Mara, the young lioness. London: Robert Hale (1966) p. 173

- Grindlay, Irene. Velvet paws: the story of Mara, the young lioness. London: Robert Hale (1966) pp. 185–186

- Grindlay, Irene. Velvet paws: the story of Mara, the young lioness. London: Robert Hale (1966) inside sleeve

- Grindlay, Irene. Velvet paws: the story of Mara, the young lioness. London: Robert Hale (1966) p. 187

- Grindlay, Irene. Velvet paws: the story of Mara, the young lioness. London: Robert Hale (1966) p. 188

- Grindlay, Irene. Velvet paws: the story of Mara, the young lioness. London: Robert Hale (1966) p. 189