Marathon world record progression

This list is a chronological progression of record times for the marathon. World records in the marathon are ratified by World Athletics, the international governing body for the sport of athletics.

Kenyan Kelvin Kiptum set a world record for men of 2:00:35 on October 8, 2023, at the 2023 Chicago Marathon.[1][2]

World Athletics recognizes two world records for women, a time of 2:14:04 set by Brigid Kosgei on October 13, 2019, during the Chicago Marathon, which was contested by men and women together, and a "Women Only" record of 2:17:01, set by Mary Keitany, on April 23, 2017, at the London Marathon for women only.[3][4] On September 24, 2023, Tigst Assefa broke the world record in a mixed-gender race by finishing the 2023 Berlin Marathon with a time of 2:11:53.[5]

Criteria for record eligibility

For a performance to be ratified as a world record by World Athletics, the marathon course on which the performance occurred must be 42.195 km (26.219 mi) long,[6] measured in a defined manner using the calibrated bicycle method[7] (the distance in kilometers being the official distance, the distance in miles is an approximation) and meet other criteria that rule out artificially fast times produced on courses aided by downhill slope or tailwind.[8] The criteria include:

- "The start and finish points of a course, measured along a theoretical straight line between them, shall not be further apart than 50% of the race distance."[6]

- "The decrease in elevation between the start and finish shall not exceed an average of one in a thousand, i.e. 1m per km."[6]

In recognizing Kenyan Geoffrey Mutai's mark of 2:03:02 at the 2011 Boston Marathon as (at the time) "the fastest Marathon ever run", the IAAF said: "Due to the elevation drop and point-to-point measurements of the Boston course, performances [on that course] are not eligible for World record consideration."[9]

Road racing events like the marathon were specifically excepted from World Athletics rule 260 18(d) that rejected from consideration those track and field performances set in mixed competition.[6]

The Association of Road Racing Statisticians, an independent organization that compiles data from road running events, also maintains an alternate marathon world best progression but with standards they consider to be more stringent.[10][11]

Women's world record

The IAAF Congress at 2011 World Championships in Athletics passed a motion changing the record eligibility criteria effective October 6, 2007, so that women's world records must be set in all-women competitions.[12] The result of the change was that Radcliffe's 2:17:42 performance at the 2005 London Marathon would supplant her own existing women's mark as the "world record"; the earlier performance was to be referred to as a "world best".[12] The decision was met with strong protest in Britain, and in November 2011 an IAAF council member reported that Radcliffe's original mark would be allowed to stand, with the eventual decision that both marks would be recognized as "world records," the faster one as a "Mixed Gender" mark, the other as a "Women Only" mark.[13] Per the 2021 IAAF Competition Rules, "a World Record for performance achieved in mixed gender ("Mixed") races and a World Record for performance achieved in single gender ("Women only") races" is tracked separately.[14]

Unofficial record attempts

In December 2016, Nike, Inc., announced that three top distance runners — Eliud Kipchoge, Zersenay Tadese and Lelisa Desisa — had agreed to forgo the spring marathon season to work with the company in an effort to run a sub-two-hour marathon, though a detailed plan to complete the marathon in 1:59:59 or faster was not released.[15][16][17][18]

The Breaking2 event took place in the early morning of May 6, 2017; Kipchoge crossed the finish line with a time of 2:00:25.[19] This time was more than two minutes faster than the world record. Among other factors, specialized pacers were used, entering the race midway to help Kipchoge keep up the pace.[20]

Kipchoge took part in a similar attempt to break the two-hour barrier in Vienna on October 12, 2019, as part of the Ineos 1:59 Challenge. He successfully ran the first sub two-hour marathon distance, with a time of 1:59:40.2.[21] The effort did not count as a new world record under IAAF rules due to the setup of the challenge. Specifically, it was not an open event, Kipchoge was handed fluids by his support team throughout, the run featured a pace car, and included rotating teams of other runners pacing Kipchoge in a formation designed to reduce wind resistance and maximize efficiency.[22][23] The achievement was recognized by Guinness World Records with the titles 'Fastest marathon distance (male)' and 'First marathon distance run under two hours'.[24][25]

History

Marathon races were first held in 1896, but the distance was not standardized by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) until 1921.[26][27] The actual distance for pre-1921 races frequently varied slightly from the norm of 42.195 km (26 miles 385 yards). In qualifying races for the 1896 Summer Olympics, Greek runners Charilaos Vasilakos (3:18:00) and Ioannis Lavrentis (3:11:27) won the first two modern marathons.[28] On April 10, 1896, Spiridon Louis of Greece won the first Olympic marathon in Athens, Greece, in a time of 2:58:50;[29] however, the distance for the event was reported to be only 40,000 meters.[30][nb 1] Three months later, British runner Len Hurst won the inaugural Paris to Conflans Marathon (also around 40 km) in a time of 2:31:30.[32] In 1900, Hurst would better his time on the same course with a 2:26:28 performance.[nb 2] Later, Shizo Kanakuri of Japan was reported to have set a world record of 2:32:45 in a November 1911 domestic qualification race for the 1912 Summer Olympics, but this performance was also run over a distance of approximately 40 km.[36][nb 3] The first marathon over the official distance was won by American Johnny Hayes at the 1908 Summer Olympics, with a time of 2:55:18.4.[38]

It is possible that Stamata Revithi, who ran the 1896 Olympic course a day after Louis, is the first woman to run the modern marathon; she is said to have finished in 5+1⁄2 hours.[39] The IAAF credits Violet Piercy's 1926 performance as the first woman to race the standard marathon distance; however, other sources report that the 1918 performance of Marie-Louise Ledru in the Tour de Paris set the initial mark for women.[10][40][41][42] Other "unofficial" performances have also been reported to be world bests or world records over time. Although her performance is not recognized by the IAAF, Adrienne Beames from Australia is frequently credited as the first woman to break the 3-hour barrier in the marathon.[43][nb 4]

In the 1953 Boston Marathon, the top three male finishers were thought to have broken the standing world record,[45] but Keizo Yamada's mark of 2:18:51 is considered to have been set on a short course of just 25.54 miles.[46] The Boston Athletic Association does not report Yamada's performance as a world best.[47] On October 25, 1981, American Alberto Salazar and New Zealander Allison Roe set apparent world bests at the New York City Marathon (2:08:13 and 2:25:29); however, these marks were invalidated when the course was later found to have been nearly 150 meters short.[48][49] Although the IAAF's progression notes three performances set on the same course in 1978, 1979, and 1980 by Norwegian Grete Waitz, the Association of Road Racing Statisticians considers the New York City course suspect for those performances, too.[50]

On April 18, 2011, the Boston Marathon produced what were at that time the two fastest marathon performances of all time. Winner Geoffrey Mutai of Kenya recorded a time of 2:03:02,[51] followed by countryman Moses Mosop in 2:03:06. However, since the Boston course does not meet the criteria for record attempts, these times were not ratified by the IAAF.

Eight IAAF world records have been set at the Polytechnic Marathon (1909, 1913, 1952–54, 1963–65).[52] IAAF world records have been broken at all of the original five World Marathon Majors on numerous occasions (updated 09/2022); twelve times at the Berlin Marathon, three times at the Boston Marathon, five times at the Chicago Marathon, six times at the London Marathon, and five times at the New York City Marathon. However, the records established in the Boston event have been disputed on grounds of a downhill point-to-point course, while four of the five New York records have been disputed on grounds of a short course.

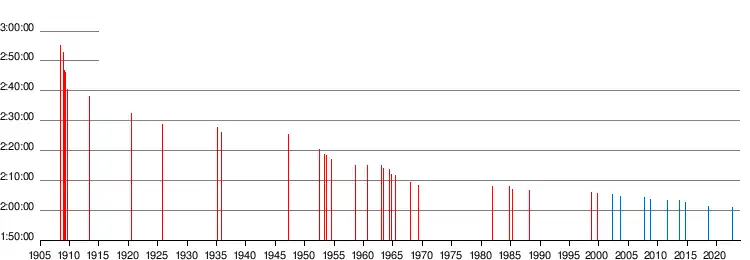

Men

Table key:

Listed by the International Association of Athletics Federations as a world best prior to official acceptance[53]

Ratified by the International Association of Athletics Federations as a world best (since January 1, 2003) or world record (since January 1, 2004)[53]

Recognized by the Association of Road Racing Statisticians (ARRS)[10]

The edition of the marathon is linked on some of the dates.

| Time | Name | Nationality | Date | Event/Place | Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2:55:18.4 | Johnny Hayes | July 24, 1908 | London Olympics, England | IAAF[53] | Time was officially recorded as 2:55:18 2/5.[54] Italian Dorando Pietri finished in 2:54:46.4, but was disqualified for receiving assistance from race officials near the finish.[55] Note.[56] | |

| 2:52:45.4 | Robert Fowler | January 1, 1909 | Yonkers,[nb 5] United States | IAAF[53] | Note.[56] | |

| 2:46:52.8 | James Clark | February 12, 1909 | New York City, United States | IAAF[53] | Note.[56] | |

| 2:46:04.6 | Albert Raines | May 8, 1909 | New York City, United States | IAAF[53] | Note.[56] | |

| 2:42:31.0 | Henry Barrett | May 8, 1909[nb 6] | Polytechnic Marathon, London, England | IAAF[53] | Note.[56] | |

| 2:40:34.2 | Thure Johansson | August 31, 1909 | Stockholm, Sweden | IAAF[53] | Note.[56] | |

| 2:38:16.2 | Harry Green | May 12, 1913 | Polytechnic Marathon | IAAF[53] | Note.[61] | |

| 2:36:06.6 | Alexis Ahlgren | May 31, 1913 | Polytechnic Marathon | IAAF[53] | Report in The Times claiming world record.[62] Note.[61] | |

| 2:38:00.8 | Umberto Blasi | November 29, 1914 | Legnano, Italy | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:32:35.8 | Hannes Kolehmainen | August 22, 1920 | Antwerp Olmpics, Belgium | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | The course distance was officially reported to be 42,750 meters/26.56 miles,[63] however, the Association of Road Racing Statisticians estimated the course to be 40 km.[31] | |

| 2:29:01.8 | Albert Michelsen | October 12, 1925 | Port Chester Marathon, United States | IAAF[53] | Note.[64][65] | |

| 2:30:57.6 | Harry Payne | July 5, 1929 | AAA Championships, London, England | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:26:14 | Sohn Kee-chung | Japanese Korea | March 21, 1935 | Tokyo, Japan | ARRS[10] | Also romanized as Kitei Son. |

| 2:27:49.0 | Fusashige Suzuki | March 31, 1935 | Tokyo, Japan | IAAF[53] | According to the Association of Road Racing Statisticians, Suzuki's 2:27:49 performance occurred in Tokyo on March 21, 1935, during a race in which he finished second to Sohn Kee-chung (sometimes referred to as Kee-Jung Sohn or Son Kitei) who ran a 2:26:14.[66] | |

| 2:26:44.0 | Yasuo Ikenaka | April 3, 1935 | Tokyo, Japan | IAAF[53] | Note.[67] | |

| 2:26:42 | Sohn Kee-chung | Japanese Korea | November 3, 1935 | Meiji Shrine Games, Tokyo, Japan | IAAF[53] | Also romanized as Kitei Son. Note.[67] |

| 2:25:39 | Suh Yun-bok | April 19, 1947 | Boston Marathon | IAAF[53] | Disputed (short course).[68] Disputed (point-to-point).[69] Note.[70] | |

| 2:20:42.2 | Jim Peters | June 14, 1952 | Polytechnic Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | MarathonGuide.com states the course was slightly long.[71] Report in The Times claiming world record.[72] | |

| 2:18:40.4 | Jim Peters | June 13, 1953 | Polytechnic Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | Report in The Times claiming world record.[72] | |

| 2:18:34.8 | Jim Peters | October 4, 1953 | Turku Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:17:39.4 | Jim Peters | June 26, 1954 | Polytechnic Marathon | IAAF[53] | Point-to-point course. Report in The Times claiming world record.[73] | |

| 2:18:04.8 | Paavo Kotila | August 12, 1956 | Finnish Athletics Championships, Pieksämäki, Finland | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:15:17.0 | Sergei Popov | August 24, 1958 | European Athletics Championships, Stockholm, Sweden | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | The ARRS notes Popov's extended time as 2:15:17.6[10] | |

| 2:15:16.2 | Abebe Bikila | September 10, 1960 | Rome Olympics, Italy | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | World record fastest marathon run in bare feet.[74] | |

| 2:15:15.8 | Toru Terasawa | February 17, 1963 | Beppu-Ōita Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:14:28 | Leonard Edelen | June 15, 1963 | Polytechnic Marathon | IAAF[53] | Point-to-point course. Report in The Times claiming world record and stating that the course may have been long.[75] | |

| 2:14:43 | Brian Kilby | July 6, 1963 | Port Talbot, Wales | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:13:55 | Basil Heatley | June 13, 1964 | Polytechnic Marathon | IAAF[53] | Point-to-point course. Report in The Times claiming world record.[76] | |

| 2:12:11.2 | Abebe Bikila | October 21, 1964 | Tokyo Olympics, Japan | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:12:00 | Morio Shigematsu | June 12, 1965 | Polytechnic Marathon | IAAF[53] | Point-to-point course. Report in The Times claiming world record.[77] | |

| 2:09:36.4 | Derek Clayton | December 3, 1967 | Fukuoka Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:08:33.6 | Derek Clayton | May 30, 1969 | Antwerp, Belgium | IAAF[53] | Disputed (short course).[78] | |

| 2:09:28.8 | Ron Hill | July 23, 1970 | Edinburgh Commonwealth Games, Scotland | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:09:12 | Ian Thompson | January 31, 1974 | Christchurch Commonwealth Games, New Zealand | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:09:05.6 | Shigeru So | February 5, 1978 | Beppu-Ōita Marathon | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:09:01 | Gerard Nijboer | April 26, 1980 | Amsterdam Marathon | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:08:18 | Robert De Castella | December 6, 1981 | Fukuoka Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:08:05 | Steve Jones | October 21, 1984 | Chicago Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:07:12 | Carlos Lopes | April 20, 1985 | Rotterdam Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:06:50 | Belayneh Dinsamo | April 17, 1988 | Rotterdam Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:06:05 | Ronaldo da Costa | September 20, 1998 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | First time the 40K mark was passed under two hours (1:59:55).[79] | |

| 2:05:42 | Khalid Khannouchi | October 24, 1999 | Chicago Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:05:38 | Khalid Khannouchi | April 14, 2002 | London Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | First "World's Best" recognized by the International Association of Athletics Federations.[80] The ARRS notes Khannouchi's extended time as 2:05:37.8[10] | |

| 2:04:55 | Paul Tergat | September 28, 2003 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | First world record for the men's marathon ratified by the International Association of Athletics Federations.[81] | |

| 2:04:26 | Haile Gebrselassie | September 30, 2007 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:03:59 | Haile Gebrselassie | September 28, 2008 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | The ARRS notes Gebrselassie's extended time as 2:03:58.2.[10] Video on YouTube | |

| 2:03:38 | Patrick Makau | September 25, 2011 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF,[82][83] ARRS[84] | ||

| 2:03:23 | Wilson Kipsang | September 29, 2013 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF[85][86] ARRS[84] | The ARRS notes Kipsang's extended time as 2:03:22.2[84] | |

| 2:02:57 | Dennis Kimetto | September 28, 2014 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF[87][88] ARRS[84] | The ARRS notes Kimetto's extended time as 2:02:56.4[84] | |

| 2:01:39 | Eliud Kipchoge | September 16, 2018 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF[89] | ||

| 2:01:09 | Eliud Kipchoge | September 25, 2022 | Berlin Marathon | World Athletics[90] | ||

| 2:00:35 | Kelvin Kiptum | October 8, 2023 | Chicago Marathon | World Athletics[91] | First man to break 2:01:00 in the marathon. |

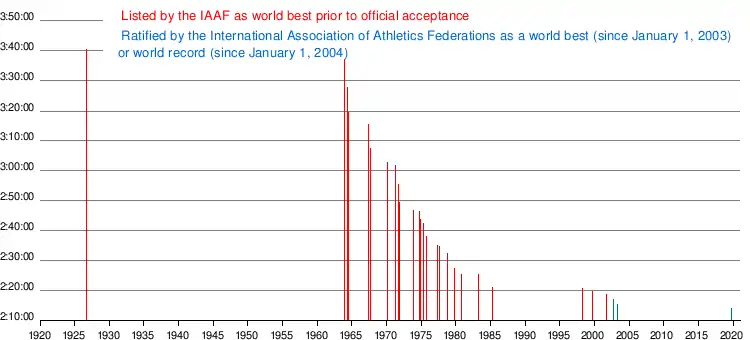

Women

Table key:

Listed by the International Association of Athletics Federations as a world best prior to official acceptance[53]

Ratified by the International Association of Athletics Federations as a world best (since January 1, 2003) or world record (since January 1, 2004)[53]

Recognized by the Association of Road Racing Statisticians (ARRS)[10]

| Time | Name | Nationality | Date | Event/Place | Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5:40:xx | Marie-Louise Ledru | September 29, 1918 | Tour de Paris Marathon | ARRS[10] | ||

| 3:40:22 | Violet Piercy | October 3, 1926 | London [nb 7] | IAAF[53] | The ARRS indicates that Piercy's 3:40:22 was set on August 2, 1926, during a time trial on a course that was only 35.4 km.[10] | |

| 3:37:07 | Merry Lepper | December 16, 1963[nb 8] | Culver City, United States | IAAF[53] | Disputed (short course).[95] | |

| 3:27:45 | Dale Greig | May 23, 1964 | Ryde | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 3:19:33 | Mildred Sampson | July 21, 1964[nb 9] | Auckland, New Zealand | IAAF[53] | Disputed by ARRS as a time trial.[nb 9][98] | |

| 3:14:23 | Maureen Wilton | May 6, 1967 | Toronto, Canada | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | The ARRS notes Wilton's extended time as 3:14:22.8[10] | |

| 3:07:27.2 | Anni Pede-Erdkamp | September 16, 1967 | Waldniel, West Germany | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | The ARRS notes Pede-Erdkamp's extended time as 3:07:26.2[10] | |

| 3:02:53 | Caroline Walker | February 28, 1970 | Seaside, OR | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 3:01:42 | Elizabeth Bonner | May 9, 1971 | Philadelphia, United States | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:55:22 | Elizabeth Bonner | September 19, 1971 | New York City Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:49:40 | Cheryl Bridges | December 5, 1971 | Culver City, United States | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:46:36 | Michiko Gorman | December 2, 1973 | Culver City, United States | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | The ARRS notes Gorman's extended time as 2:46:37[10] | |

| 2:46:24 | Chantal Langlacé | October 27, 1974 | Neuf-Brisach, France | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:43:54.5 | Jacqueline Hansen | December 1, 1974 | Culver City, United States | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | The ARRS notes Hansen's extended time as 2:43:54.6[10] | |

| 2:42:24 | Liane Winter | April 21, 1975 | Boston Marathon | IAAF[53] | Disputed (point-to-point).[69] | |

| 2:40:15.8 | Christa Vahlensieck | May 3, 1975 | Dülmen | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:38:19 | Jacqueline Hansen | October 12, 1975 | Nike OTC Marathon, Eugene, United States | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:35:15.4 | Chantal Langlacé | May 1, 1977 | Oiartzun, Spain | IAAF[53] | ||

| 2:34:47.5 | Christa Vahlensieck | September 10, 1977 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:32:29.8 | Grete Waitz | October 22, 1978 | New York City Marathon | IAAF[53] | Disputed (short course).[50][101] | |

| 2:27:32.6 | Grete Waitz | October 21, 1979 | New York City Marathon | IAAF[53] | Disputed (short course).[50][102] | |

| 2:31:23 | Joan Benoit | February 3, 1980 | Auckland, New Zealand | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:30:57.1 | Patti Catalano | September 6, 1980 | Montreal, Canada | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:25:41.3 | Grete Waitz | October 26, 1980 | New York City Marathon | IAAF[53] | Disputed (short course).[50][103] | |

| 2:30:27 | Joyce Smith | November 16, 1980 | Tokyo, Japan | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:29:57 | Joyce Smith | March 29, 1981 | London Marathon | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:25:28 | Allison Roe | October 25, 1981 | New York City Marathon | IAAF[53] | Disputed (short course).[50][104] | |

| 2:29:01.6 | Charlotte Teske | January 16, 1982 | Miami, United States | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:26:12 | Joan Benoit | September 12, 1982 | Nike OTC Marathon, Eugene, United States | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:25:28.7 | Grete Waitz | April 17, 1983 | London Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:22:43 | Joan Benoit | April 18, 1983 | Boston Marathon | IAAF[53] | Disputed (point-to-point).[69] | |

| 2:24:26 | Ingrid Kristiansen | May 13, 1984 | London Marathon | ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:21:06 | Ingrid Kristiansen | April 21, 1985 | London Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:20:47 | Tegla Loroupe | April 19, 1998 | Rotterdam Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:20:43 | Tegla Loroupe | September 26, 1999 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:19:46 | Naoko Takahashi | September 30, 2001 | Berlin Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:18:47 | Catherine Ndereba | October 7, 2001 | Chicago Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | ||

| 2:17:18 | Paula Radcliffe | October 13, 2002 | Chicago Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | First "World's Best" recognized by the International Association of Athletics Federations.[80] The ARRS notes Radcliffe's extended time as 2:17:17.7[10] | |

| 2:15:25 Mx | Paula Radcliffe | April 13, 2003 | London Marathon | IAAF,[53] ARRS[10] | First world record for the women's marathon ratified by the International Association of Athletics Federations.[105] The ARRS notes Radcliffe's extended time as 2:15:24.6[10] | |

| 2:17:42 Wo | Paula Radcliffe | April 17, 2005 | London Marathon | IAAF[106] | ||

| 2:17:01 Wo | Mary Jepkosgei Keitany | April 23, 2017 | London Marathon | IAAF[107] | ||

| 2:14:04 Mx | Brigid Kosgei | October 13, 2019 | Chicago Marathon | IAAF[108] | ||

| 2:11:53 Mx | Tigst Assefa | September 24, 2023 | Berlin Marathon | World Athletics[109] | First woman to break the 2:12:00 barrier in the marathon.[110] |

Gallery of world record holders

See also

Men's Masters Records

- Masters M35 marathon world record progression

- Masters M40 marathon world record progression

- Masters M45 marathon world record progression

- Masters M50 marathon world record progression

- Masters M55 marathon world record progression

- Masters M60 marathon world record progression

- Masters M65 marathon world record progression

- Masters M70 marathon world record progression

- Masters M75 marathon world record progression

- Masters M80 marathon world record progression

- Masters M85 marathon world record progression

- Masters M90 marathon world record progression

- Masters M100 marathon world record progression

Women's Masters Records

- Masters W35 marathon world record progression

- Masters W40 marathon world record progression

- Masters W45 marathon world record progression

- Masters W50 marathon world record progression

- Masters W55 marathon world record progression

- Masters W60 marathon world record progression

- Masters W65 marathon world record progression

- Masters W70 marathon world record progression

- Masters W75 marathon world record progression

- Masters W80 marathon world record progression

- Masters W85 marathon world record progression

- Masters W90 marathon world record progression

Notes

- The Association of Road Racing Statisticians has estimated the course distance to be 37–38 km.[31]

- According to the "Sporting Records" section of The Canadian Year Book for 1905: "Len Hurst won the Marathon race, 40 kilometres (24 miles, 1505 yards), over roads, Conflans to Paris, Fr., in the record time of 2.26:27 3–5, July 8, 1900."[33] Other sources confirm that the direction of the 1900 race was reversed but note Hurst's finishing time as 2:26:47.4[34] or 2:26:48.[35]

- Road running historian Andy Milroy writing for the Association of Road Racing Statisticians has indicated that "25 miles was the distance of the first Japanese marathon held in 1911". Predating Kanakuri's performance, Milroy also indicated that a "professional world record" at the 25-mile distance of 2:32:42 was set by British runner Len Hurst on August 27, 1903.[37]

- According to the Association of Road Racing Statisticians, Beames' performance of 2:46:30 on August 31, 1971, in Werribee, Australia is regarded as a time trial.[44]

- Many references incorrectly refer to this race as the Yonkers Marathon. The Yonkers Marathon, which during the early 1900s was traditionally run during late November, was won over a month earlier by Jim Crowley.[57][58]

- According to the progression of world bests listed by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), James Clark set a world best of 2:46:52.8 in New York on February 12, 1909, Albert Raines broke Clark's mark with a 2:46:04.6 in New York on May 8, 1909, and Henry Barrett broke Raines' mark with a 2:42:31.0 in London on May 26, 1909.[59] Ian Ridpath, a former director of the Polytechnic marathon, has indicated on his website that some sources have wrongly listed the date of Barrett performance as May 26, 1909, and has confirmed the true date as May 8, 1909.[52] An article in The Times dated May 10, 1909, provides strong evidence that Ridpath is correct.[60] Given that Barrett's marathon in London most likely concluded before Raines' marathon held on the same date in New York, it is also likely that Barrett rather than Raines broke the world best set by Clark three months earlier.

- Piercy's mark was set on the Polytechnic Marathon course between Windsor and London.[92] A number of sources, including Kathrine Switzer, have reported that the venue for Piercy's mark was the actual Polytechnic Marathon,[93] however, records from the Association of Road Racing Statisticians confirm that the 1926 Polytechnic Marathon was held on May 18.[94]

- The Association of Road Racing Statisticians notes the date of the race as December 14, 1963.[95][96]

- Peter Heidenstrom, a statistician for Athletics New Zealand, has been reported as providing a date of December 1964,[97] however, the Association of Road Racing Statisticians notes the date of Sampson's performance was August 16, 1964.[98] Other sources from August to October 1964 support the August date.[99][100] The ARRS also notes that Sampson's mark was set during a time trial and does not recognize it in their progression of marathon world bests.[10][95]

References

- "Kelvin Kiptum nearly breaks two-hour barrier with world marathon record". Washington Post. October 8, 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- "Chicago Marathon 2023: Kelvin Kiptum smashes Eliud Kipchoge's world record". International Olympic Committee. October 8, 2023. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- "Women's outdoor Marathon - Records - iaaf.org". iaaf.org. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- "Interactive: A look at how three marathoners could break the sub-2hr barrier on May 6". The Straits Times. May 5, 2017. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- "Tigist Assefa shatters women's marathon record in new £400 shoes". The Guardian. September 24, 2023. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- "IAAF Competition Rules 2016–2017" (PDF). 2015. p. 275. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "IAAF Publication, "The Measurement of Road Race Courses", Second Edition, 2004, Updated 2008" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- May, Peter (April 18, 2011). "Kenya's Mutai Wins Boston in 2:03:02". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- Monti, David (April 18, 2011). "Strong winds and ideal conditions propel Mutai to fastest Marathon ever – Boston Marathon report". iaaf.org. International Association of Athletics Federations. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ARRS World Best Progressions – Road 2015.

- "Association of Road Racing Statisticians". ARRS. January 1, 2003. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- Baldwin, Alan (September 20, 2011). "Argument erupts over Radcliffe's marathon record". Reuters.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- "Paula Radcliffe keeps her marathon world record in IAAF about-turn". The Guardian. London. November 10, 2011. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- IAAF Book of Rules. Vol. Book C – C1.1. IAAF. 2021. p. 32. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- Ed Caesar (December 12, 2016). "Inside Nike's Quest for the Impossible: a Two-Hour Marathon". Wired. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- Alex Hutchinson (December 12, 2016). "Nike's Audacious Plan: Break the 2-Hour Marathon Barrier in 2017". Runner's World. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- Ross Tucker, PhD (December 13, 2016). "The sub-2 hour marathon in 2017? Thoughts on concept". The Science of Sport. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- "Interactive: A look at how three marathoners could break the sub-2hr barrier on May 6". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- Jon Mulkeen (May 6, 2017). "Kipchoge a 'happy man' in Monza". IAAF. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- Eliud Kipchoge falls 26 seconds short of first sub two-hour marathon Archived September 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 7-May-2017

- INEOS. "INEOS 1:59 Challenge". ineos159challenge.com. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Derek Hawkins (October 12, 2019). "Kenya's Eliud Kipchoge Just Became the First Person to Break the 2-Hour Barrier". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 12, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- Agnew, Mark (October 12, 2019). "Eliud Kipchoge runs sub two-hour marathon in 1:59:40, making history with first four-minute mile equivalent". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on October 12, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- "Fastest marathon distance (male)". Guinness World Records. October 12, 2019. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- "First marathon distance run under two hours". Guinness World Records. October 12, 2019. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- "The Marathon journey to reach 42.195km". european-athletics.org. April 25, 2008. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- Martin, David E.; Roger W. H. Gynn (May 2000). The Olympic Marathon. Human Kinetics Publishers. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-88011-969-6.

- Martin, Dr. David (2000). "Marathon running as a social and athletic phenomenon: historical and current trends". In Pedoe, Dan Tunstall (ed.). Marathon Medicine. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press. p. 31. ISBN 9781853154607.

- De Coubertin, Pierre; Timoleon J. Philemon; N. G. Politis; Charalambos Anninos (1897). "The Olympic Games, B.C. 776 – A.D. 1896, Second Part, The Olympic Games in 1896" (PDF). Charles Beck (Athens), H. Grevel and Co. (London). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "Athletes | Olympic Medalist | Olympians | Gold Medalists | Medal Count". International Olympic Committee. July 19, 1996. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- "untitled". Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- Milroy, Andy. "The origins of the marathon". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- "Sporting Records". The Canadian Year Book for 1905. Toronto Canada: Alfred Hewitt. 8: 147. 1905.

- Martin, David E.; Roger W. H. Gynn (May 2000). The Olympic Marathon. Human Kinetics Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-88011-969-6.

- Noakes, Tim (2003). The Lore of Running (Fourth ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-87322-959-2.

- "Running Training Blog Entry | Lydiard Foundation Members". Lydiardfoundation.org. July 15, 1912. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- "ARRS – Association of Road Racing Statisticians". Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- "Profiles – Johnny Hayes". Running Past. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- Tarasouleas, Athanasios (October–November 1997). "Stamata Revithi, "Alias Melpomeni"" (PDF). Olympic Review. 26 (17): 53–55. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- "Tour de Paris Marathon". ARRS. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- Fast Tracks: The History of Distance Running Since 884 B.C. by Raymond Krise, Bill Squires. (1982).

- Endurance by Albert C. Gross. (1986)

- Howe, Charles. "Out of the bushes, ahead of the ambulance, and into the spotlight: milestones in the history of women's (mostly distance) running, Part I" (PDF). Rundynamics. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1971". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Unverified (probably a time trial)

- "Boston Marathon history". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1953". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2009.

Short Course (41.1 km)

- 114th B.A.A Boston Marathon Official Program. April 19, 2010.

- "World Marathon Major Event Records" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2011.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1981". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Short Course (150 m short on remeasurement)

- "New York City Marathon". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

The course used for the 1981 race was remeasured at 42.044 km or 151 meters short of the full marathon distance. Since a major part of the shortness was within the Central Park portion of the course, all "five borough" races prior to 1981 must also be considered suspect (1976–1980) and are not considered acceptable for statistical purposes.

- "Mutai wins Boston in world-record time: Kilel edges American in women's race". Boston Herald. Associated Press. April 18, 2011. Archived from the original on April 21, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- "The Polytechnic Marathon 1909–1996". Ianridpath.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- IAAF Statistics Handbook – Daegu 2011.

- Cook, Theodore Andrea (1909). "The Fourth Olympiad being The Official Report The Olympic Games of 1908" (PDF). The British Olympic Association, London. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "Athletes | Olympic Medalist | Olympians | Gold Medalists | Medal Count". International Olympic Committee. July 19, 1996. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- "Men's World Record Times – 1905 to 1911". Marathonguide.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Yonkers Marathon Archived January 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- "J.F. CROWLEY WINS YONKERS MARATHON; Irish-American Runner Leads Big Field Over Westchester County Roads". The New York Times. November 27, 1908. p. 7. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- "12th IAAF World Championships In Athletics: IAAF Statistics Handbook. Berlin 2009" (PDF). Monte Carlo: IAAF Media & Public Relations Department. 2009. p. 565. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "Image: 1909Timesreport.jpg, (550 × 1188 px)". ianridpath.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Men's World Record Times – 1910 to 1916". Marathonguide.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "Image: 1913Timesreport.jpg, (434 × 452 px)". ianridpath.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Olympic Games Official Report 1920" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 8, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "Whitey Michelsen". Archived from the original on October 5, 2013.

- "Men's World Record Times – 1922 to 1928". Marathonguide.com. October 12, 1925. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1935". ARRS. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "Men's World Record Times – 1932 to 1938". Marathonguide.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1947". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Short Course (25.54 mi. = 41.1 km)

- The Association of Road Racing Statisticians does not consider performances on the Boston Marathon course to qualify for world record status due to the possibility that they could be aided by slope and/or tailwinds. (See Archived January 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.) This mirrors the IAAF's current criteria regarding record eligible courses.

- "Men's World Record Times – 1944 to 1950". Marathonguide.com. April 19, 1947. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "Men's World Record Times – 1949 to 1955". Marathonguide.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "Image: 1952Timesreport.jpg, (359 × 1700 px)". ianridpath.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Image: 1954Timesreport.jpg, (339 × 1244 px)". ianridpath.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Guinness World Records fastest marathon run in bare feet". guinnessworldrecords.com. September 10, 1960. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- "Image: 1963Timesreport.jpg, (1733 × 1242 px)". ianridpath.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Image: 1964Timesreport.jpg, (1362 × 1353 px)". ianridpath.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Image: 1965Timesreport.jpg, (704 × 1260 px)". ianridpath.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1969". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Short Course (ca 500 m short)

- "2021 New York Marathon Statistical Information" (PDF). germanroadraces.de. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 23, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- "Stat Corner: First World Road Records," Track and Field News, Volume 56, No. 2, February 2003, Page 50

- "Del's Athletics Almanac Olympics Commonweath European World Championship Results [Event Information]". Athletics.hitsites.de. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "Makau stuns with 2:03:38 marathon world record in Berlin". World Athletics. September 25, 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- "World records ratified". World Athletics. December 20, 2011. Archived from the original on October 8, 2023. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- "World Best Progression- Road". ARRS. May 3, 2016. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- "Kipsang sets world record of 2:03:23 at Berlin Marathon | iaaf.org". IAAF. September 29, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "World Record Ratified | iaaf.org". IAAF. November 12, 2013. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "Kimetto breaks marathon world record in Berlin with 2:02:57 | iaaf.org". IAAF. September 28, 2014. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "World Record Ratified | iaaf.org". IAAF. November 24, 2014. Archived from the original on November 27, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "Kipchoge breaks world record in Berlin with 2:01:09". IAAF. October 26, 2018. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- "Kipchoge breaks world record in Berlin with 2:01:09 | REPORT | World Athletics". worldathletics.org. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- "Kiptum smashes world marathon record with 2:00:35, Hassan runs 2:13:44 in Chicago". World Athletics. October 8, 2023. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- Noakes, Tim (2003). The Lore of Running (Fourth ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 675. ISBN 0-87322-959-2.

- "Washington Running Report – Feature Article". Runwashington.com. February 23, 1981. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- "untitled". Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- "Western Hemisphere Marathon". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1963". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- Jutel, Anne-Marie (2007). "Forgetting Millie Sampson: Collective Frameworks for Historical Memory". New Zealand Journal of Media Studies. 10 (1): 31–36. doi:10.11157/medianz-vol10iss1id74.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1964". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Note: Mildred Sampson (NZL) ran 3:19:33 in a time trial on 16 Aug 1964 at Auckland NZL.

- "Housewife's Marathon Record Run". The Age. Melbourne. August 18, 1964. p. 22. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- Rogin, Gilbert (October 5, 1964). "The Fastest Is Faster". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

One Saturday last August, a Mrs. Millie Sampson, a 31-year-old mother of two who lives in the Auckland suburb of Manurewa, went dancing until 1 am The next day she cooked dinner for 11 visitors. In between, she ran the marathon in 3:19.33, presumably a record.

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1978". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Short Course (measurements on subsequent course were 150 m short, this course probably short as well)

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1979". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Short Course (measurements on subsequent course were 150 m short, this course probably short as well)

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1980". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Short Course (remeasurements of a nearly identical course in 1981 was 150 m short, this course probably short as well)

- "World Marathon Rankings for 1980". Association of Road Racing Statisticians. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

Short Course (remeasurements of a nearly identical course in 1981 was 150 m short, this course probably short as well)

- "Del's Athletics Almanac Olympics Commonweath European World Championship Results [Event Information]". Athletics.hitsites.de. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- "IAAF Statistic Handbook Beijing 2015". IAAF. 2015. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- "Keitany breaks women's-only world record at London Marathon". IAAF. April 23, 2017. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- "World Record Progression of Marathon". iaaf.org. IAAF. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- "Assefa smashes world marathon record in Berlin with 2:11:53, Kipchoge achieves record fifth win". World Athletics. September 24, 2023. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- "Tigst Assefa Sets Womens Marathon Record in 2023 Berlin Marathon". letsrun.com. September 24, 2023. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

Sources

- "untitled". ARRS. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- Butler, Mark, ed. (2011). 13th IAAF World Championships in Athletics – IAAF Statistics Handbook – Daegu 2011 (PDF). Part 5 (of 5). IAAF Media & Public Relations Department. pp. 595, 612, 614–615, 705, 707. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 3, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

External links

- 13th IAAF World Championships in Athletics – IAAF Statistics Handbook – Daegu 2011 (all 5 parts)

- Runner's World | What Will It Take to Run A 2-Hour Marathon?

- BBC – "Could a marathon ever be run in under two hours?"

- Interactive graph of men's and women's marathon times with race descriptions (outdated)

_Marathon_1936_Summer_Olympics.jpg.webp)

_2023.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)