Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Sophia Charlotte; 19 May 1744 – 17 November 1818) was Queen of Great Britain and Ireland as the wife of George III from their marriage on 8 September 1761 until her death in 1818. As George's wife, she was also Electress of Brunswick-Lüneburg (Hanover) until becoming Queen of Hanover on 12 October 1814. Charlotte was Britain's longest-serving queen consort, serving for 57 years and 70 days.

Charlotte was born into the ruling family of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, a duchy in northern Germany. In 1760, the young and unmarried George III inherited the British throne. As Charlotte was a minor German princess with no interest in politics, George considered her a suitable consort, and they married in 1761. The marriage lasted 57 years and produced 15 children, 13 of whom survived to adulthood. They included two future British monarchs, George IV and William IV; as well as Charlotte, Princess Royal, who became Queen of Württemberg; and Prince Ernest Augustus, who became King of Hanover.

Charlotte was a patron of the arts and an amateur botanist who helped expand Kew Gardens. She introduced the Christmas tree to Britain, decorating one for a Christmas party for children of Windsor in 1800. She was distressed by her husband's bouts of physical and mental illness, which became permanent in later life. She maintained a close relationship with Queen Marie Antoinette of France, and the French Revolution is likely to have enhanced the emotional strain felt by Charlotte. Her eldest son, George, was appointed prince regent in 1811 due to the increasing severity of the King's illness. Charlotte died in November 1818 with her son George at her side. George III died a little over a year later, probably unaware of his wife's death.

Early life

Sophia Charlotte was born on 19 May 1744. She was the youngest daughter of Duke Charles Louis Frederick of Mecklenburg, Prince of Mirow (1708–1752), and his wife Princess Elisabeth Albertine of Saxe-Hildburghausen (1713–1761). Mecklenburg-Strelitz was a small north-German duchy in the Holy Roman Empire.[2]

The children of Duke Charles were all born at the Unteres Schloss (Lower Castle) in Mirow.[3] According to diplomatic reports at the time of her engagement to George III in 1761, Charlotte had received "a very mediocre education".[4] Her upbringing was similar to that of a daughter of an English country gentleman.[5] She received some rudimentary instruction in botany, natural history, and language from tutors, but her education focused on household management and religion – the latter taught by a priest. Only after her brother Adolphus Frederick succeeded to the ducal throne, in 1752, did she gain any experience of princely duties and of court life.[6]

Marriage

When George III succeeded to the throne of Great Britain upon the death of his grandfather George II, he was 22 years old and unmarried. His mother, Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, and his advisors were eager to have him settled in marriage. The 17-year-old Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz appealed to him as a prospective consort partly because she had been brought up in an insignificant north German duchy, and therefore would probably have had no experience or interest in power politics or party intrigues. That proved to be the case; to make sure, he instructed her shortly after their wedding "not to meddle", a precept she was glad to follow.[7]

The King announced to his Council in July 1761, according to the usual form, his intention to wed the Princess, after which a party of escorts, led by the Earl Harcourt, departed for Germany to conduct Princess Charlotte to England. They reached Strelitz on 14 August 1761, and were received the next day by Duke Adolphus Frederick IV, Charlotte's brother, at which time the marriage contract was signed by him on the one hand and Lord Harcourt on the other. Three days of public celebrations followed, and on 17 August 1761, Charlotte set out for Britain, accompanied by Adolphus Frederick and the British escort party. On 22 August, they reached Cuxhaven, where a small fleet awaited to convey them to England. The voyage was extremely difficult; the party encountered three storms at sea, and landed at Harwich only on 7 September. They set out at once for London, spent that night in Witham, at the residence of Lord Abercorn, and arrived at 3:30 pm the next day at St. James's Palace in London. They were received by the King and his family at the garden gate, which marked the first meeting of the bride and groom.

At 9:00 pm that same evening (8 September 1761), within six hours of her arrival, Charlotte was united in marriage with King George III. The ceremony was performed at the Chapel Royal, St. James's Palace, by the archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Secker.[8] Only the royal family, the party who had travelled from Germany, and a handful of guests were present.[8] George and Charlotte's coronation was held at Westminster Abbey a fortnight later on 22 September.

Queen consort

Upon her wedding day, Charlotte spoke no English. However, she quickly learned the language, albeit speaking with a strong German accent. One observer commented, "She is timid at first but talks a lot, when she is among people she knows."[9]

_with_her_Two_Eldest_Sons_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Less than a year after the marriage, on 12 August 1762, the Queen gave birth to her first child, George, Prince of Wales. In the course of their marriage, the couple became the parents of 15 children,[10] all but two of whom (Octavius and Alfred) survived into adulthood.[11][12][13]

St James's Palace functioned as the official residence of the royal couple, but the King had recently purchased a nearby property, Buckingham House, located at the western end of St James's Park. More private and compact, the new property stood amid rolling parkland not far from St James's Palace. Around 1762 the King and Queen moved to this residence, which was originally intended as a private retreat. The Queen came to favour this residence, spending so much of her time there that it came to be known as The Queen's House. Indeed, in 1775, an Act of Parliament settled the property on Queen Charlotte in exchange for her rights to Somerset House.[14] Most of the couple's 15 children were born in Buckingham House, although St James's Palace remained the official and ceremonial royal residence.[15][lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3]

During her first years in Great Britain, Charlotte's strained relationship with her mother-in-law, Augusta, caused her difficulty in adapting to the life of the British court.[6] Augusta interfered with Charlotte's efforts to establish social contacts by insisting on rigid court etiquette.[6] Furthermore, Augusta appointed many of Charlotte's staff, among whom several were expected to report to Augusta about Charlotte's behaviour.[6] Charlotte turned to her German companions for friends, notably her close confidante Juliane von Schwellenberg.[6]

The King enjoyed country pursuits and riding and preferred to keep his family's residence as much as possible in the then rural towns of Kew and Richmond. He favoured an informal and relaxed domestic life, to the dismay of some courtiers more accustomed to displays of grandeur and strict protocol. Lady Mary Coke was indignant on hearing in July 1769 that the King, the Queen, her visiting brother Prince Ernest and Lady Effingham had gone for a walk through Richmond town by themselves without any servants. "I am not satisfied in my mind about the propriety of a Queen walking in town unattended."[17]

From 1778 the royal family spent much of their time at a newly constructed residence, the Queen's Lodge at Windsor, opposite Windsor Castle, in Windsor Great Park, where the King enjoyed hunting deer.[18] The Queen was responsible for the interior decoration of their new residence, described by a friend of the royal family and diarist Mary Delany: "The entrance into the first room was dazzling, all furnished with beautiful Indian paper, chairs covered with different embroideries of the liveliest colours, glasses, tables, sconces, in the best taste, the whole calculated to give the greatest cheerfulness to the place."[17]

Charlotte treated her children's attendants with friendly warmth which is reflected in this note she wrote to her daughters' assistant governess, Mary Hamilton:

My dear Miss Hamilton, What can I have to say? Not much indeed! But to wish you a good morning, in the pretty blue and white room where I had the pleasure to sit and read with you The Hermit, a poem which is such a favourite with me that I have read it twice this summer. Oh! What a blessing to keep good company! Very likely I should not have been acquainted with either poet or poem was it not for you.[19]

Charlotte did have some influence on political affairs through the King. Her influence was discreet and indirect, as demonstrated in the correspondence with her brother Charles. She used her closeness with George III to keep herself informed and to make recommendations for offices.[20] Apparently her recommendations were not direct, as she on one occasion, in 1779, asked her brother Charles to burn her letter, because the King suspected that a person she had recently recommended for a post was the client of a woman who sold offices.[20] Charlotte particularly interested herself in German issues. She took an interest in the War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–1779), and it is possible that it was due to her efforts that the King supported British intervention in the continuing conflict between Joseph II and Charles Theodore of Bavaria in 1785.[20]

Husband's first period of illness

When the King had his first, temporary, bout of mental illness in 1765, her mother-in-law and Lord Bute kept Charlotte unaware of the situation. The Regency Bill of 1765 stated that if the King should become permanently unable to rule, Charlotte was to become regent. Her mother-in-law and Lord Bute had unsuccessfully opposed this arrangement, but as the King's illness of 1765 was temporary, Charlotte was aware neither of it, nor of the Regency Bill.[6]

The King's bout of physical and mental illness in 1788 distressed and terrified the Queen. The writer Frances Burney, at that time one of the Queen's attendants, overheard her moaning to herself with "desponding sound": "What will become of me? What will become of me?"[21] When the King collapsed one night, she refused to be left alone with him and successfully insisted that she be given her own bedroom. When the doctor, Warren, was called, she was not informed and was not given the opportunity to speak with him. When told by the Prince of Wales that the King was to be removed to Kew, but that she should move to Queen's House or to Windsor, she successfully insisted that she accompany her spouse to Kew. However, she and her daughters were taken to Kew separately from the King and lived secluded from him during his illness. They regularly visited him, but the visits tended to be uncomfortable, as he had a tendency to embrace them and refuse to let them go.[6]

During the 1788 illness of the King, a conflict arose between the Queen and the Prince of Wales, who were both suspected of desiring to assume the regency should the illness of the King become permanent, resulting in him being declared unfit to rule. Charlotte suspected her son of a plan to have the King declared insane with the assistance of Doctor Warren, and to take over the regency.[6] Prince George's followers, notably Sir Gilbert Ellis, in turn suspected Queen Charlotte of a plan to have King George declared sane with the assistance of Doctor Willis and Prime Minister Pitt, so that he could have her appointed regent should he fall ill again, and then have him declared insane again and assume the regency.[6] According to Doctor Warren, Doctor Willis had pressed him to declare the King sane on the orders of the Queen.[6]

In the Regency Bill of 1789, the Prince of Wales was declared regent should the King become permanently insane, but it also placed the King himself, his court and minor children under the guardianship of the Queen.[6] The Queen used this Bill when she refused the Prince of Wales permission to see the King alone, even well after he had been declared sane again in the spring of 1789.[6] The conflict around the regency led to serious discord between the Prince of Wales and his mother.[6] In an argument he accused her of having sided with his enemies, while she called him the enemy of the King.[6] Their conflict became public when she refused to invite him to the concert held in celebration of the recovery of the King, which created a scandal.[6] During this period, Queen Charlotte was caricatured in satirical prints which depicted her as an unnatural mother and a creature of the Prime Minister.[22] In January 1789 The Times accused the Opposition of beginning "a most scurrilous attack on the Queen, not only by private conversation, but through the medium of the prints in their interest".[23] Queen Charlotte and the Prince of Wales finally reconciled, on her initiative, in March 1791.[6]

As the King gradually became permanently insane, the Queen's personality altered: she developed a terrible temper, sank into depression, and no longer enjoyed appearing in public, not even at the musical concerts she had so loved; and her relationships with her adult children became strained.[24] From 1792 she found some relief from her worry about her husband by planning the gardens and decoration of a new residence for herself, Frogmore House, in Windsor Home Park.[25]

From 1804 onward, when the King displayed declining mental health, Queen Charlotte slept in a separate bedroom, had her meals separate from him, and avoided seeing him alone.[6]

Interests and patronage

King George III and Queen Charlotte were music connoisseurs with German tastes, who gave special honour to German artists and composers. They were passionate admirers of the music of George Frideric Handel.[26]

In April 1764, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, then aged eight, arrived in Britain with his family as part of their grand tour of Europe and remained until July 1765.[27] The Mozarts were summoned to court on 19 May and played before a limited circle from six to ten o'clock. Johann Christian Bach, eleventh son of the great Johann Sebastian Bach, was then music-master to the Queen. He put difficult works of Handel, J. S. Bach, and Carl Friedrich Abel before the boy: he played them all at sight, to the amazement of those present.[28] Afterwards, the young Mozart accompanied the Queen in an aria which she sang, and played a solo work on the flute.[29] On 29 October, the Mozarts were in London again, and were invited to court to celebrate the fourth anniversary of the King's accession. As a memento of the royal favour, Leopold Mozart published six sonatas composed by Wolfgang, known as Mozart's Opus 3, that were dedicated to the Queen on 18 January 1765, a dedication she rewarded with a present of 50 guineas.[30]

Queen Charlotte was an amateur botanist who took a great interest in Kew Gardens. In an age of discovery, when such travellers and explorers as Captain James Cook and Sir Joseph Banks were constantly bringing home new species and varieties of plants, she ensured that the collections were greatly enriched and expanded.[31] Her interest in botany led to the South African flower, the bird of paradise, being named Strelitzia reginae in her honour.[32]

Queen Charlotte has also been credited with introducing the Christmas tree to Britain and its colonies.[33] Initially, Charlotte decorated a single yew branch, a common Christmas tradition in her native Mecklenburg-Strelitz, to celebrate Christmas with members of the royal family and the royal household.[34] She decorated the branch with the assistance of her ladies-in-waiting and then had the court gather to sing carols and distribute gifts.[34] In December 1800, Queen Charlotte set up the first known English Christmas tree at Queen's Lodge, Windsor.[34][35] That year, she held a large Christmas party for the children of all the families in Windsor and placed a whole tree in the drawing-room, decorated with tinsel, glass, baubles and fruits.[34] John Watkins, who attended the Christmas party, described the tree in his biography of the queen: "from the branches of which hung bunches of sweetmeats, almonds and raisins in papers, fruits and toys, most tastefully arranged; the whole illuminated by small wax candles. After the company had walked round and admired the tree, each child obtained a portion of the sweets it bore, together with a toy, and then all returned home quite delighted."[34] The practice of decorating a tree became popular among the British nobility and gentry, and later spread to the colonies.[33][34]

Among the royal couple's favoured craftsmen and artists were the cabinetmaker William Vile, silversmith Thomas Heming, the landscape designer Capability Brown, and the German painter Johann Zoffany, who frequently painted the King and Queen and their children in charmingly informal scenes, such as a portrait of Queen Charlotte and her children as she sat at her dressing table.[36] In 1788 the royal couple visited the Worcester Porcelain Factory (founded in 1751, and later to be known as Royal Worcester), where Queen Charlotte ordered a porcelain service that was later renamed "Royal Lily" in her honour. Another well-known porcelain service designed and named in her honour was the "Queen Charlotte" pattern.[37]

The queen founded orphanages and, in 1809, became the patron (providing new funding) of the General Lying-in Hospital, a hospital for expectant mothers. It was subsequently renamed as the Queen's Hospital, and is today the Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital.[38] The education of women was of great importance to her, and she ensured that her daughters were better educated than was usual for young women of the day; however, she also insisted that her daughters live restricted lives close to their mother, and she refused to allow them to marry until they were well-advanced in years. As a result, none of her daughters had surviving legitimate issue (one, Princess Charlotte, had a stillborn daughter during her marriage; another, Princess Sophia, may have had an illegitimate son).[39]

Up until 1788, portraits of Charlotte often depict her in maternal poses with her children, and she looks young and contented;[40] however, in that year her husband fell seriously ill and became temporarily insane. It is now thought that the King had porphyria,[41] though bipolar disorder has also been named as another possible underlying cause for his condition.[42][43][44] Sir Thomas Lawrence's portrait of Charlotte at this time marks a transition point, after which she looks much older in her portraits; the assistant keeper of Charlotte's wardrobe, Charlotte Papendiek, wrote that the Queen was "much changed, her hair quite grey".[45]

Friendship with Marie Antoinette

The French Revolution of 1789 probably added to the strain that Charlotte felt.[47] Queen Charlotte and Queen Marie Antoinette of France had maintained a close relationship. Charlotte was 11 years older than Marie Antoinette, yet they shared many interests, such as their love of music and the arts, about which they were both enthusiastic. Never meeting face to face, they confined their friendship to pen and paper. Marie Antoinette confided in Charlotte upon the outbreak of the French Revolution. Charlotte had organized apartments to be prepared and ready for the refugee royal family of France to occupy.[48] She was greatly distraught when she heard the news that the King and Queen of France had been executed.

During the Regency

After the onset of his permanent madness in 1811, George III was placed under the guardianship of his wife in accordance with the Regency Bill of 1789.[6] She could not bring herself to visit him very often, due to his erratic behaviour and occasional violent reactions. It is believed she did not visit him again after June 1812. However, Charlotte remained supportive of her spouse as his illness worsened in old age. While her son, the Prince Regent, wielded the royal power, she was her spouse's legal guardian from 1811 until her death in 1818. Due to the extent of the King's illness he was incapable of knowing or understanding that she had died.[49]

During the Regency of her son, Queen Charlotte continued to fill her role as first lady in royal representation because of the estrangement of the Prince Regent and his spouse.[6] As such, she functioned as the hostess by the side of her son at official receptions, such as the festivities given in London to celebrate the defeat of Emperor Napoleon in 1814.[6] She also supervised the upbringing of her granddaughter, Princess Charlotte of Wales.[6] During her last years, she was met with a growing lack of popularity and was sometimes subjected to demonstrations.[6] After having attended a reception in London on 29 April 1817, she was jeered by a crowd. She told the crowd that it was upsetting to be treated like that after such long service.[6]

Death

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_4534916.jpg.webp)

The Queen died in the presence of her eldest son, the Prince Regent, who was holding her hand as she sat in an armchair at the family's country retreat, Dutch House in Surrey (now known as Kew Palace).[50] She was buried at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[51] Her husband died just over a year later. She is the longest-serving female consort and second-longest-serving consort in British history (after Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh), having served as such from her marriage (on 8 September 1761) to her death (17 November 1818), a total of 57 years and 70 days.[52]

On the day before her death, the Queen dictated her will to her husband's secretary, Sir Herbert Taylor, appointing him and Lord Arden as her executors; at her death, her personal estate was valued at less than £140,000 (equivalent to £10,100,000 in 2019[53]), with her jewels accounting for the greater portion of her assets.[54] In her will, proven at Doctor's Commons on 8 January 1819, the Queen bequeathed her husband the jewels she had received from him, unless he remained in his state of insanity, in which case the jewels were to become an heirloom of the House of Hanover. Other jewels, including some gifted to the Queen by the Nawab of Arcot, were to be evenly distributed among her surviving daughters. The furnishings and fixtures at the royal residence at Frogmore, along with "live and dead stock...on the estates", were bequeathed to her daughter Augusta Sophia along with the Frogmore property, unless its maintenance would prove too expensive for her daughter, in which case it was to revert to the Crown. Her youngest daughter Sophia inherited the Royal Lodge.[54] Certain personal assets that the Queen had brought from Mecklenburg-Strelitz were to revert to the senior branch of that dynasty, while the remainder of her assets, including her books, linen, art objects and china, were to be evenly divided among her surviving daughters.[54]

At the Queen's death, her eldest son, the Prince Regent, claimed Charlotte's jewels, and on his death they were in turn claimed by his heir, William IV. On William's death, Charlotte's bequest then sparked a protracted dispute between her granddaughter Queen Victoria, who claimed the jewels as the property of the British Crown, and Charlotte's now eldest-surviving son Ernest, who claimed the jewels by right of being the most senior male member of the House of Hanover. The dispute would not be resolved in Ernest's lifetime. Eventually in 1858, over twenty years after the death of William IV and nearly forty years after Charlotte's death, the matter was decided in favour of Ernest's son George, upon which Victoria had the jewels given into the custody of the Hanoverian ambassador.[55]

The rest of Charlotte's property was sold at auction from May to August 1819. Her clothes, furniture, and even her snuff were sold by Christie's.[56] It is highly unlikely that her husband ever knew of her death. He died blind, deaf, lame and insane 14 months later.[57]

Legacy

Places named after Charlotte include the Queen Charlotte Islands (now known as Haida Gwaii) in British Columbia, Canada, and Queen Charlotte City on Haida Gwaii; Queen Charlotte Sound (not far from the Haida Gwaii Islands); Queen Charlotte Channel (near Vancouver, Canada); Queen Charlotte Bay in West Falkland; Queen Charlotte Sound, South Island, New Zealand; several fortifications, including Fort Charlotte, Saint Vincent; Charlottesville, Virginia; Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island; Charlotte, North Carolina;[58] Mecklenburg County, North Carolina; Mecklenburg County, Virginia; Charlotte County, Virginia; Charlotte County, Florida; Port Charlotte, Florida; Charlotte Harbor, Florida; and Charlotte, Vermont. The proposed North American colonies of Vandalia[59][60][61] and Charlotina were also named for her.[62] In Tonga, the royal family adopted the name Sālote (the Tongan version of Charlotte) in her honour, and notable individuals included Sālote Lupepauʻu and Sālote Tupou III.[63]

Charlotte's provision of funding to the General Lying-in Hospital in London prevented its closure; today it is named Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital, and is an acknowledged centre of excellence amongst maternity hospitals. A large copy of the Allan Ramsay portrait of Queen Charlotte hangs in the main lobby of the hospital.[38] The Queen Charlotte's Ball, an annual debutante ball that originally funded the hospital, is named after her.[64]

A lead statue probably of Queen Charlotte, dating to c. 1775, stands on Queen Square in Bloomsbury, London,[65][66] and there are two statues of her in Charlotte, North Carolina: at Charlotte Douglas International Airport[67] and at the International Trade Center.[68]

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, was chartered in 1766 as Queen's College, in reference to Queen Charlotte.[69] It was renamed in 1825 in honour of Henry Rutgers, a Revolutionary War officer and college benefactor. Its oldest extant building, Old Queen's (built 1809–1823), and the city block that forms the historic core of the university, Queen's Campus, retain their original names.[70]

Queen Charlotte was played by Frances White in the 1979 television series Prince Regent, by Helen Mirren in the 1994 film The Madness of King George,[71] by Golda Rosheuvel in the 2020 Netflix original series Bridgerton,[72] and by India Amarteifio in Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story.

Strelitzia, a genus of flowering plants native to South Africa that has become ubiquitous in warm-weather regions worldwide, is named for Charlotte's native Mecklenburg-Strelitz.[73]

Arms

The royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom are impaled with her father's arms as a Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. The arms were: Quarterly of six, 1st, Or, a buffalo's head cabossed Sable, armed and ringed Argent, crowned and langued Gules (Mecklenburg); 2nd, Azure, a griffin segreant Or (Rostock); 3rd, Per fess, in chief Azure, a griffin segreant Or, and in the base Vert, a bordure Argent (Principality of Schwerin); 4th, Gules, a cross patée Argent crowned Or (Ratzeburg); 5th, Gules, a dexter arm Argent issuant from clouds in sinister flank and holding a finger ring Or (County of Schwerin); 6th, Or, a buffalo's head Sable, armed Argent, crowned and langued Gules (Wenden); Overall an inescutcheon, per fess Gules and Or (Stargard).[74]

The Queen's arms changed twice to mirror the changes in her husband's arms, once in 1801 and then again in 1816. A funerary hatchment displaying the Queen's full coat of arms, painted in 1818, is on display at Kew Palace.[75][76]

.svg.png.webp) Arms of Queen Charlotte, from 1816 to 1818

Arms of Queen Charlotte, from 1816 to 1818.svg.png.webp) Arms of Queen Charlotte, from 1801 to 1816

Arms of Queen Charlotte, from 1801 to 1816.svg.png.webp) Arms of Queen Charlotte, from 1761 to 1801

Arms of Queen Charlotte, from 1761 to 1801

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes[77] |

|---|---|---|---|

| George IV | 12 August 1762 | 26 June 1830 | (1) married 1785 Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert, marriage legally invalid as George III had not consented to the match. (2) 1795, Princess Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel; had issue (Princess Charlotte of Wales); no surviving descendants today |

| Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany | 16 August 1763 | 5 January 1827 | married 1791, Princess Frederica of Prussia; no issue |

| William IV | 21 August 1765 | 20 June 1837 | married 1818, Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen; no surviving legitimate issue, but had illegitimate issue |

| Charlotte, Princess Royal | 29 September 1766 | 6 October 1828 | married 1797, King Frederick of Württemberg; no surviving issue |

| Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn | 2 November 1767 | 23 January 1820 | married 1818, Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld; had issue (Queen Victoria) |

| Princess Augusta Sophia | 8 November 1768 | 22 September 1840 | never married, no issue |

| Princess Elizabeth | 22 May 1770 | 10 January 1840 | married 1818, Frederick VI, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg; no issue |

| Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover | 5 June 1771 | 18 November 1851 | married 1815, Princess Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz; had issue (King George V of Hanover) |

| Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex | 27 January 1773 | 21 April 1843 | (1) married in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act 1772, The Lady Augusta Murray; had issue; marriage annulled 1794 (2) married 1831, The Lady Cecilia Buggin (later 1st Duchess of Inverness); no issue |

| Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge | 24 February 1774 | 8 July 1850 | married 1818, Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel; had issue |

| Princess Mary | 25 April 1776 | 30 April 1857 | married 1816, Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh; no issue |

| Princess Sophia | 3 November 1777 | 27 May 1848 | never married, no issue |

| Prince Octavius | 23 February 1779 | 3 May 1783 | died in childhood |

| Prince Alfred | 22 September 1780 | 20 August 1782 | died in childhood |

| Princess Amelia | 7 August 1783 | 2 November 1810 | never married, no issue |

Ancestry

Claims that Queen Charlotte may have had black African or mixed ancestry first emerged in Racial Mixture as the Basic Principle of Life published in 1929 by German historian, Brunold Springer, who challenged her Thomas Gainsborough portrait as inaccurate.[79] Based on her alternative portrait by Allan Ramsay and contemporary descriptions of her appearance, Springer concluded that the queen's "broad nostrils and heavy lips" must point to African heritage. Jamaican-American amateur historian J. A. Rogers agreed with Springer in his 1940 book Sex and Race: Volume I,[80][81] where he concluded that Queen Charlotte must be "biracial"[82] or "black".[78][83][84]

_-_Queen_Charlotte_(1744-1818)_-_RCIN_405308_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

Proponents of the African ancestry claim also hold to a literal interpretation of Baron Stockmar's diary, in which he described Charlotte as "small and crooked, with a real Mulatto face". Stockmar, who served as personal physician to the queen's granddaughter's husband Leopold I of Belgium, arrived at court just two years before Charlotte's death in 1816. His descriptions of Charlotte's children in this same diary are equally unflattering.[85]

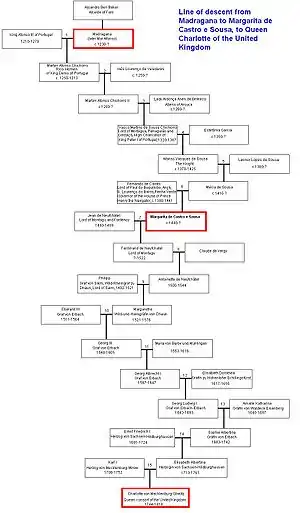

In 1997, Mario de Valdes y Cocom, an independent researcher about Black diaspora,[86][83] popularized and expanded on earlier arguments in an article for PBS Frontline,[87] which has since been cited as the main source by a number of articles on the topic.[88][89][90][91] Valdes also seized on Charlotte's 1761 Allan Ramsay portrait as evidence of African ancestry, citing the queen's "unmistakable African appearance" and "negroid physiogomy" [sic].[87] Valdes claimed that Charlotte had inherited these features from one of her distant ancestors, Madragana (born c. 1230), a mistress of King Afonso III of Portugal (c. 1210 – 1279).[92] His conclusion is based on various historical sources that describe Madragana as either Moorish[93] or Mozarab,[94] which Valdes interpreted to mean that she was black.[84]

Although popular among the general public, the claims are largely denounced by most scholars.[95][81][96][97][84] Aside from Stockmar's jibe at her appearance shortly before her death, Charlotte was never referred to as having any specifically African physical features, let alone ancestry, during her lifetime. Furthermore, her portraiture was not atypical for her time, and painted portraits in general should not be considered reliable evidence of a sitter's true appearance.[97] The use of the term "Moor" as a racial identifier for Charlotte's ancestor Madragana is also inconclusive as during the Middle Ages the term was not used to describe race but religious affiliation.[98][99] Regardless, Madragana was more likely Mozarab,[100][101][102][103] and any genetic contribution from an ancestor fifteen generations removed would be so diluted as to have a negligible affect on her appearance.[96][84] Historian Andrew Roberts describes the claims as "utter rubbish", and attributes its public popularity to a hesitancy among historians to openly address it due to its "cultural cringe factor".[95]

In 2017, following the announcement of the engagement of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, a number of news articles were published promoting the claims.[88][82][104] David Buck, a Buckingham Palace spokesperson, was quoted by the Boston Globe as saying: "This has been rumoured for years and years. It is a matter of history, and frankly, we've got far more important things to talk about."[105] In 2023, after the filming of the Netflix series Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, in which the monarch was played by British actress with Ghanaian-German origins India Amarteifio, media attention on her origins was rekindled.[106][107][108]

| Ancestors of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz[109] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

-

- Queen consort of the United Kingdom from 1 January 1801 onwards, following the Acts of Union 1800.

- Queen consort of Hanover from 12 October 1814 onwards.

- The tradition persists of foreign ambassadors being formally accredited to "the Court of St James's", even though they present their credentials and staff, upon their appointment, to the Monarch at Buckingham Palace.

- The house which forms the architectural core of the present palace was built for the first Duke of Buckingham and Normanby in 1703 to the design of William Winde. Buckingham's descendant, Sir Charles Sheffield, sold Buckingham House to George III in 1761.

- The building in the distance is Eton College Chapel, as seen from Windsor Castle.

References

- Panton, James (24 February 2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press. p. xxxv. ISBN 978-0-8108-7497-8.

- Fitzgerald (1899), pp. 5–6

- Wurlitzer, Bernd; Sucher, Kerstin (2010). Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Mit Rügen und Hiddensee, Usedom, Rostock und Stralsund. Trescher Verlag. p. 313. ISBN 978-3897941632.

- Fraser 2005, p. 16.

- Fitzgerald 1899, p. 7.

- Fitzgerald (1899)

- Jean L. Cooper and Angelika S. Powell (2003). "Queen Charlotte from her Letters". University of Virginia. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Fitzgerald (1899), pp. 32–33

- Fraser 2005, p. 17.

- "Charlotte, Queen of England". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- "St. James's, May 6". The London Gazette (12437): 1. May 1783.

- Weir 2008, p. 300.

- Holt 1820, p. 251.

-

Walford, Edward (1878). "Westminster: Buckingham Palace". Old and New London. Vol. 4. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin. pp. 61–74. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

In 1775 the property was legally settled, by Act of Parliament, on Queen Charlotte (in exchange for Somerset House, [...]); and henceforth Buckingham House was known in West-end society as the "Queen's House."

- Westminster: Buckingham Palace, Old and New London: Volume 4 (1878), pp. 61–74. Date accessed: 3 February 2009

- Levey 1977, pp. 8–9.

- Fraser 2005, p. 23.

- "Berkshire History". Queen's Lodge. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Fraser 2005, p. 72.

- Campbell Orr, Clarissa: Queenship in Europe 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort. Cambridge University Press (2004)

- Fraser 2005, p. 116.

- Garrett, Natalee. "Albion's Queen by All Admir'd': Reassessing the Public Reputation of Queen Charlotte, 1761–1818". Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies (2022) 45 (3): pp. 6–9

- The Times, 15 January 1789, cited in Garrett 2022, p. 9

- Fraser 2005, pp. 112–379 passim.

- "Berkshire History". Frogmore House. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Jahn, Otto; Grove, Sir George (1882). Life of Mozart. Vol. 1. p. 39.

- Engel, Louis: From Mozart to Mario: Reminiscences of half a century, Volume 1, 1886, p. 275.

- Engel, Louis. From Mozart to Mario: Reminiscences of Half a Century, Volume 1, 1886, p. 39.

- Gehring, Franz Eduard. Mozart, 1911, p. 18.

- Jahn & Grove 1882, p. 41

- Murray, John. A Handbook for Travellers in Surrey, Hampshire, and the Isle of Wight, 1876, pp. 130–131.

- "Bird of Paradise Flower (Strelitzia Reginae)". Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden. 10 (2): 27. 1922 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Simmons, John D. (10 December 2021). "How Queen Charlotte Mecklenburg brought Christmas tree here". The Charlotte Observer. Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S.: McClatchy Company. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- Barnes, Alison (12 December 2006). "The First Christmas Tree". History Today. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- Sommerlad, Joe (21 December 2018). "Why Queen Charlotte Really Deserves The Credit For Bringing The Christmas Tree To Britain". The Independent. London, U.K.: Independent Digital News & Media Ltd. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- Levey 1977, p. 4

- Appendix III of Flight & Barr Worcester Porcelain by Henry Sandon.

- Ryan, Thomas (1885). The History of Queen Charlotte's Lying-in Hospital from its foundation in 1752 to the present time, with an account of its objects and present state. Hutchings & Crowsley.

- Beatty, Michael A. (2003). The English Royal Family of America, From Jamestown to the American Revolution. McFarland & Company. p. 229. ISBN 0-7864-1558-4.

- Levey 1977, pp. 7–8

- Cox, Timothy M.; Jack, N.; Lofthouse, S.; Watling, J.; Haines, J.; Warren, M. J. (2005). "King George III and porphyria: an elemental hypothesis and investigation". The Lancet. 366 (9482): 332–335. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66991-7. PMID 16039338. S2CID 13109527.

- Peters, Timothy J.; Wilkinson, D. (2010). "King George III and porphyria: a clinical re-examination of the historical evidence". History of Psychiatry. 21 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1177/0957154X09102616. PMID 21877427. S2CID 22391207.

- Peters, T. (June 2011). "King George III, bipolar disorder, porphyria and lessons for historians". Clinical Medicine. 11 (3): 261–264. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.11-3-261. PMC 4953321. PMID 21902081.

- Rentoumi, V.; Peters, T.; Conlin, J.; Gerrard, P. (2017). "The acute mania of King George III: A computational linguistic analysis". PLOS One. 3 (12): e0171626. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1271626R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171626. PMC 5362044. PMID 28328964.

- Levey 1977, p. 7

- Levey 1977, p. 16

- Levey 1977, p. 15

- Fraser, Antonia: Marie Antoinette: The Journey, 2001; p. 287.

- Ayling 1972, pp. 453–455; Brooke 1972, pp. 384–385; Hibbert 1999, p. 405

- Fitzgerald 1899, pp. 258–260

- "Royal Burials in the Chapel since 1805". College of St George - Windsor Castle. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- "Prince Philip, the longest-serving British monarch consort, dies aged 99". Guinness World Records. 9 April 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "The Late Queen's Will". The Times. 9 January 1819.

- Van der Kiste, John (2004), George III's Children (revised ed.), Stroud, United Kingdom: Sutton Publishing Ltd, ISBN 978-0-7509-3438-1

- Baker, Kenneth (2005), George IV: A Life in Caricature. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 114. ISBN 978-0-500-25127-0.

- Brooke, p. 386

- Bernstein, Viv (3 September 2012). "Welcome to Charlotte, a City of Quirks". The Caucus. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Otis K. Rice and Stephen W. Brown. West Virginia: A History. 2nd edn. University Press of Kentucky, 1994, p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8131-1854-3.

- David W. Miller, The Taking of American Indian Lands in the Southeast: A History of Territorial Cessions and Forced Relocations, 1607–1840. McFarland, 2011, p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7864-6277-3.

- Thomas J. Schaeper. Edward Bancroft: Scientist, Author, Spy. Yale University Press, 2011, p. 34. ISBN 978-0-300-11842-1.

- "The Expediency of Securing Our American Colonies, &c." (1763), p. 14. Reprinted in The Critical Period, 1763–1765. Volume 10 of the Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library. Clarence Walworth Alvord, ed. Illinois State Historical Library, 1915, p. 139.

- Wood-Ellem, Elizabeth (1999). Queen Sālote of Tonga: The Story of an Era 1900–1965. Auckland, N.Z: Auckland University Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2529-4. OCLC 262293605.

- Millington, Alison. "Inside Queen Charlotte's Ball, the glamorous, Champagne-filled event for affluent debutantes from around the world". Business Insider. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Historic England. "Statue of a Queen at north end of Queen Square Gardens (1245488)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- Sculptures, Bloomsbury Squares & Gardens. Wordpress. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- "Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg, Charlotte". Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina. 19 March 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "Queen Charlotte Walks in Her Garden, Charlotte". Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina. 19 March 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- A Historical Sketch of Rutgers University Archived 22 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine by Thomas J. Frusciano, University Archivist. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Barr, Michael C. and Wilkens, Edward. National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form for Queens Campus at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey (1973). Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- Maslin, Janet (1994). "Going Mad Without Being a Sore Loser". New York Times. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Andrea Park (30 December 2020). "What 'Bridgerton' Got Right About Queen Charlotte". Marie Claire. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- "Strelitzia reginae Banks". Plants of the World Online. 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974). The Royal Heraldry of England. Heraldry Today. Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press. p. 297. ISBN 0-900455-25-X.

- "Queen Charlotte's Hatchment returns to Kew", The Seaxe, No. 56, September 2009.

- Queen Charlotte's hatchment Archived 1 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Historic Royal Palaces website: Surprising stories. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- Kiste, John Van der (2004). George III's Children. The History Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0750953825.

- Chabaku, Motlalepula (3 February 1989). "Queen's Features Altered". The Charlotte Observer.

- Gregory, Bethany (2016). Commemorating Queen Charlotte: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Memory, 1750 to 2014 (Master of Arts). The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. p. 27.

- Rogers Freire, J. A. (1967). "Sex and Race: Negro-Caucasian Mixing in All Ages and All Lands, Volume I: The Old World". p. 206. Retrieved 20 February 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- "Explained: What we know of Queen Charlotte, claimed to be 'Britain's Black queen'". The Indian Express. 23 March 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Blakemore, Erin. "Meghan Markle Might Not Be the First Mixed-Race British Royal". Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- Ungoed-Thomas, Jon; Goncalves, Eduardo (6 June 1999). "Revealed: The Queen's Black Ancestors". The Sunday Times.

- Stuart Jeffries, "Was this Britain's first black queen?" The Guardian, 12 March 2009.

- von Stockmar, Christian Friedrich (1872). Memoirs of Baron Stockmar. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 50.

- "Contributor Mario Valdes". Huffington Post. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

Independent researcher specializing in still relatively unexplored areas of black history and the black image.

- de Valdes y Cocom, Mario. "The Blurred Racial Lines of Famous Families: Queen Charlotte". Frontline. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Brown, DeNeen (28 November 2017). "Britain's black queen: Will Meghan Markle really be the first mixed-race royal?". Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Park, Andrea (30 December 2020). "What 'Bridgerton' Got Right About Queen Charlotte". Marie Claire. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Brown, DeNeen (25 February 2021). "Was Queen Charlotte Black? Here's what we know". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Owen, Nathalie (12 February 2021). "The real story behind Queen Charlotte from Bridgerton". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Mario de Valdes y Cocom "The blurred racial lines of famous families – Queen Charlotte", PBS Frontline.

- LEAO, Duarte Nunes de, Primeira parte das Chronicas dos reis de Portvgal (sheet 97)

- Sousa, António Caetano de, História Genealógica da Casa Real Portuguesa, Tomo XII, Parte II (pp. 702 & 703)

- Linge, Mary (13 November 2021). "Real-life queen of 'Bridgerton' wasn't biracial – but she was a badass". New York Post. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Hilton, Lisa (28 January 2020). "The "mulatto" Queen Lisa Hilton Debunks a Growing Myth About a Monarch's Consort". TheCritic.co.uk. TheCritic. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Jill Sudbury (20 September 2018). "Royalty, Race and the Curious Case of Queen Charlotte". Acacia Tree Books. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Blackmore, Josiah (2009). Moorings: Portuguese Expansion and the Writing of Africa. U of Minnesota Press. pp. xvi, 18. ISBN 978-0-8166-4832-0.

- Menocal, María Rosa (2002). Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. Little, Brown, & Co. ISBN 0-316-16871-8, p. 241

- "Primeira parte das Chronicas dos reis de Portvgal". purl.pt. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Braamcamp Freire, Anselmo (14 September 1921). "Brasões da Sala de Sintra". Coimbra : Imprensa da Universidade. Retrieved 14 September 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Felgueiras Gayo & Carvalhos de Basto, Nobiliário das Famílias de Portugal, Braga, 1989

- Pizarro, José Augusto de Sotto Mayor, Linhagens Medievais Portuguesas, 3 vols., Porto, Universidade Moderna, 1999.

- Bates, Karen Grigsby. "The Meaning Of Meghan: 'Black' And 'Royal' No Longer An Oxymoron In Britain". Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Deneen Brown, "Prince Harry and Meghan Markle wedding: Will the bride really be our first mixed-race royal?" The Independent, 28 November 2017.

- Lang, Cady (5 May 2023). "The True Story Behind Netflix's 'Queen Charlotte'". Time. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Berman, Judy (8 May 2023). "'Queen Charlotte' Fixes What Was Broken About 'Bridgerton'". Time. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Richardson, Kalia (11 May 2023). "Here's What to Know About 'Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 84.

Bibliography

- Ayling, Stanley (1972). George the Third. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-211412-7.

- Barr, Michael C. and Wilkens, Edward (1973). National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form for Queens Campus at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- Brooke, John (1972). King George III. London: Constable. ISBN 0-09-456110-9.

- Fitzgerald, Percy (1899). The Good Queen Charlotte. Downey Publishing. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Fraser, Flora (2005). Princesses: The Six Daughters of George III. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-45118-8.

- Garrett, Natalee (2022). "Albion's Queen by All Admir'd': Reassessing the Public Reputation of Queen Charlotte, 1761-1818". Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies. 45 (3): 351–370. doi:10.1111/1754-0208.12822. S2CID 246071347.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1999). George III: A Personal History. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-025737-3.

- Holt, Edward (1820). The public and domestic life of His late Most Gracious Majesty, George the Third. Vol. 1. London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones.

- Levey, Michael (1977). A Royal Subject: Portraits of Queen Charlotte. London: National Gallery.

- Weir, Alison (2008). Britain's Royal Families, The Complete Genealogy. London: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-09-953973-5.

Further reading

- Drinkuth, Friederike (2011). Queen Charlotte. A Princess from Mecklenburg-Strelitz ascends the Throne of England. Thomas Helms Verlag Schwerin. ISBN 978-3-940207-79-1.

- Hedley, Olwen (1975). Queen Charlotte. J Murray. ISBN 0-7195-3104-7.

- Kassler, Michael, ed. (2015). "The Diary of Queen Charlotte, 1789 and 1794". Memoirs of the Court of George III. Vol. 4. London: Pickering & Chatto. ISBN 978-1-8489-34696.

- Kassler, Michael (2019). "Queen Charlotte's 1789 Account Book". Eighteenth-Century Life. 43 (3): 86–100. doi:10.1215/00982601-7725749. S2CID 208688081.

- Sedgwick, Romney (June 1960). "The Marriage of George III". History Today. Vol. 10, no. 6. pp. 371–377.

External links

![]() Media related to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz at Wikimedia Commons

- Queen Charlotte at the official website of the British monarchy

- Queen Charlotte at the official website of the Royal Collection Trust

- Queen Charlotte, 1744–1818: A Bilingual Exhibit (c. 1994)

- "The Blurred Racial Lines of Famous Families – Queen Charlotte" at the PBS site

- "Archival material relating to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz". UK National Archives.

- Stuart Jeffries, "Was this Britain's first black queen?" The Guardian (12 March 2009)

- Portraits of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz at the National Portrait Gallery, London

.svg.png.webp)