Marguerite Zorach

Marguerite Zorach (née Thompson; September 25, 1887 – June 27, 1968) was an American Fauvist painter, textile artist, and graphic designer, and was an early exponent of modernism in America. She won the 1920 Logan Medal of the Arts.[1]

Marguerite Zorach | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Zorach in her studio | |

| Born | Marguerite Thompson September 25, 1887 |

| Died | June 27, 1968 (aged 80) New York City, US |

| Known for | painting |

| Spouse | |

| Awards | Logan Medal |

Early life

Marguerite Thompson was born in Santa Rosa, California.[2]: 14 Her father, a lawyer for Napa Valley vineyards, and mother were descended from New England seafarers and Pennsylvania Quakers. While she was young, the family moved to Fresno and it was there that she began her education. She started to draw at a very young age and her parents provided her with an education that was heavily influenced by the liberal arts, including music lessons in elementary school, and four years of Latin at Fresno High School. She was one of a small group of women admitted to Stanford University in 1908.[3][2]: 58

Career

Paris and travel

While at Stanford, Thompson continued to show aptitude for art, and rather than completing her degree, she traveled to France at the invitation of her aunt, Harriet Adelaide Harris.[4] Marguerite visited the Salon d'Automne the very day that she arrived in Paris. Here, she saw many works by Henri Matisse and André Derain, known as the Fauvists, or Wild Beasts. The Fauvists became known for their use of arbitrary colors and spontaneous, instinctive brushwork. Thompson's encounters with these works had a strong impact on her. It was the intention of her aunt that Thompson attend the École des Beaux-Arts, but Thompson was turned away as she had never drawn a nude from life. Harris then attempted to have Thompson enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, to study under the academic painter Francis Auburtin. Thompson had no interest in the formulas of academic painting and instead she chose to attend the post-impressionist school Académie de La Palette, where she studied under John Duncan Fergusson and Jacques-Emile Blanche.[5] The academy encouraged her to pursue her own interests and paint in a style that was uniquely her own. She exhibited at the 1910 Société des Artistes Indépendants, and the 1911 Salon d'Automne, both renowned for their modernist themes.

While in Paris, she socialized with Pablo Picasso, ex-patriate Gertrude Stein, Henri Rousseau, and Henri Matisse through her "Aunt Addie's" connections.[6] At the Académie de La Palette, she first met her future husband and artistic collaborator, William Zorach. William admired her passionate individuality, and he said of her modernist Fauvist artwork "I just couldn't understand why such a nice girl would paint such wild pictures."[7]

After Paris, she took a lengthy tour of the world with her aunt in 1911–12. They visited Jerusalem, Egypt, India, Burma, China, Hong Kong, Japan, and Hawaii. Impressed with the foreign places she had seen and eager to write about her experiences, she sent articles to her childhood newspaper, the Fresno Morning Republican.[6] This trip would also have a huge effect on her art, influencing her to paint even more abstractly than she had in the past, sometimes even completely flat. She also began to produce brightly colored Fauvist landscapes with thick black outlines. The trip ended with a return to California in 1912.[8]

Return to the US and marriage

After Thompson returned to Fresno, she spent July and August in the mountains to the north-east of Fresno around Big Creek and Shaver Lake. The lower Sierra Nevada mountains appealed to her because of their immensity and natural beauty. Ultimately, her parents' disapproval of her artistic pursuits would end her time there and cause her to destroy a large amount of her work. Upon her return to the US, she exhibited in Fresno and Los Angeles. Soon, she moved to New York City and married William Zorach the same day, December 24, 1912. The couple immediately began to collaborate artistically. Both entered artwork in the 1913 Armory Show. Their success continued as both were invited to participate in the 1916 Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters.[5] It was at this time that William and Marguerite began to experiment with other art forms such as poetry.[6]

Marguerite gave birth to a son, Tessim Zorach, in 1915, and a daughter, Dahlov Zorach, in 1917. Eventually, the pair settled in Greenwich Village and fondly called their house the "Post-Impressionist" studio. It became a meeting place of sorts, reminiscent of small salons in Paris for artists to collaborate and share ideas. At Marguerite's insistence the family spent the summers in the countryside of New England. In 1922, they visited Gaston Lachaise at Georgetown, Maine, and later bought a house. They were friends with Marsden Hartley, F. Holland Day, Gertrude Kasebier, and Paul Strand.[9]

Marguerite also served as the president of the modernist New York Society of Women Artists in the mid-1920s.[10]

Summer in Yosemite

One of Marguerite and William's most influential summers was in 1920 when they spent the summer in Yosemite Valley, painting the landscape.[11] The couple, with their family, hiked, sketched, and painted the beautiful national park in the Fauvist style. The trip greatly moved the two, and themes from the trip would appear in many of their later works, including Marguerite's works Memories of my California Childhood (1921) and Nevada Falls, Yosemite Valley, California (1920).

Textile art

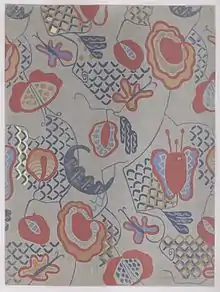

After the birth of their daughter, Marguerite found that working with textiles would allow her to give more attention to her children. While both William and Marguerite experimented with textile art, Marguerite was more prolific and better-known for her work. She created mainly embroideries or batiks that stylistically resembled her Fauvist paintings. Her embroideries were first shown in New York in 1918, to a positive response. Using textiles as a medium followed the modernist patterns of the turn of the century as new art became increasingly less narrative. It broke down the barriers between crafts and fine art, and William and Marguerite's collaboration broke down gender barriers.[12] Her works were popular and interesting to the public, but art critics gave them mixed reviews because of the low status of embroidery within the fine arts. Today they are celebrated for their feminist subjects and innovative style.[13] Zorach's first exhibition was at Charles David's gallery in New York. Many times the sales of Marguerite's textiles are what kept the family from poverty.[5] Zorach also took great delight in making clothes for her husband and children, although they were not always the conventional style of the times.[12]

Later years and death

Marguerite Zorach continued to be a prolific artist until the end of her life. In later years, she worked for the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression. Her 1938 oil-on-canvas mural in the lobby at the Peterborough, New Hampshire post office, entitled New England Post in Winter, showed her modernist talent. In 1940, she completed the mural Autumn for the WPA in Ripley, Tennessee. Marguerite also taught at Columbia University.[5]

Later in life, she suffered from macular degeneration in her eyes. This greatly inhibited her ability to produce textiles, however she was able to continue painting.

She died in New York in 1968.[5]

While Zorach was an impressive and prolific artist, it was not until after her death that she received the same recognition as her husband. She was a talented painter who was influential in progressing artistic Modernism in the United States.[12] Many art historians consider her the "First Woman Artist of California."[14]

Museum holdings and public works

The Smithsonian American Art Museum has over two hundred pieces of Zorach's in their collection.[15] The collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has several Zorach oils and watercolors.[16]

The Monticello, Indiana post office contains her 1942 Section of Fine Arts mural entitled Hay Making.

Honors and retrospectives

In 1964, Zorach received a D.F.A. from Bates College. In 2007, the Gerald Peters Gallery held a retrospective exhibition of her work.[17] In 2010, her watercolors were exhibited at the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.[18] In 2011, a retrospective was held at Franklin & Marshall College.[19]

Bibliography

- Colleary, Elizabeth Thompson. Marguerite Thompson Zorach, American Modernist. New York: College of New Rochelle, 1993.

- Fowler, Cynthia. The Modern Embroidery Movement. London: Bloomsbury, 2018.

- Fowler, Cynthia. "Marguerite Zorach: American Modernism and Craft Production in the First Half of the 20th Century." PhD diss. University of Delaware, 2002.

- Hoffman, Marilyn Friedman. Marguerite and William Zorach: The Cubist Years, 1915-1918. Manchester, NH: Currier Gallery of Art, 1987.

- Nicoll, Jessica. Marguerite & William Zorach: Harmonies and Contrasts. Portland, ME: Portland Museum of Art, 2001.

- Swinth, Kirsten. Painting Professionals: Women Artists & the Development of Modern American Art. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Tarbell, Roberta K. William and Marguerite Zorach: The Maine Years. Rockland, ME: William A. Farnsworth Library and Art Museum, 1979.

- Zorach, Marguerite. Clever Fresno Girl: The Travel Writings of Marguerite Thompson Zorach (1908-1915). Edited by Efram L. Burk. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2008.

References

- "Marguerite Thompson Zorach". IFPDA. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- Zorach, Marguerite (1973). Marguerite Zorach: the Early Years, 1908-1920. National Collection of Fine Arts.

- Rubenstein, Charlotte Streifer, American Women Artists: from Early Indian Times to the Present, Avon Publishers 1982 p, 7.

- "To Be Modern: The Origins of Marguerite and William Zorach's Creative Partnership, 1911-1922; essay by Jessica Nicoll". Tfaoi.com. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- "Marguerite Thompson Zorach". CLARA Database of Women Artists. National Museum of Women in the Arts. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- Burk, Efram L. (2004). "The Graphic Art of Marguerite Thompson Zorach". Woman's Art Journal. 25 (1): 12–17. doi:10.2307/3566493. JSTOR 3566493.

- Zorach, William (1967). Art is My Life: The Autobiography of William Zorach. World Publishing Company. p. 23.

- Colleary, Elizabeth T. "Marguerite Thompson Zorach: Some Newly Discovered." Woman's Art Journal 23.1 (Spring-Summer 2002): 24-28. JSTOR. Web.

- Deborah Weisgall. "Marguerite Zorach: Georgetown Goes Modern: The Modern Art Movement Meets an Island Community". The Maine Magazine.

- Zorach, Marguerite (2008). Clever Fresno Girl: The Travel Writings of Marguerite Thompson Zorach (1908-1915). Associated University Presse. p. 86. ISBN 9780874130355.

- Burk, Efram L. "Sketching and Painting in Ecstasy--William and Marguerite Zorach in Yosemite Valley, Summer 1920." Southeastern College Art Conference Review 16(4) (2014): 459-71. Web.

- Clark, Hazel (1995). "The Textile Art of Marguerite Zorach". Woman's Art Journal. 16 (1): 18–25. doi:10.2307/1358626. JSTOR 1358626.

- {Cynthia Fowler, The Modern Embroidery Movement}

- "Marguerite Zorach and William Zorach: June 4 – August 13, 2010". Michael Rosenfeld Gallery website, 2010.

- "Artworks Search Results". Smithsonian Museum of American Art. Retrieved 2017-02-11.

- "Marguerite Zorach". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2017-02-11.

- Smith, Roberta (2007-06-01). "ART IN REVIEW; Marguerite Zorach -- A Life in Art". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- "Marguerite Zorach and William Zorach - Exhibitions". Michael Rosenfeld Art. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- Wright, Mary Ellen (2011-10-09). "F&M to host Zorach exhibit - Entertainment". LancasterOnline.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

External links

- Official website

- "Marguerite Zorach", Smithsonian Museum of American Art

- "Marguerite Zorach", Gerald Peters Gallery