Tocopilla nitrate railway

The María-Elena - Tocopilla line was the last operating nitrate railway in Chile, and last operating section of a railway system that moved caliche ore to processing plants and nitrate to the port of Tocopilla. It was a magnet for rail fans before closing in August 2015 after severe rainfall damaged the tracks to the extent that the owner decided it was beyond economic repair.

High above Tocopilla, an iconic Boxcab leads a train down to Reverso | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main region(s) | Plains of Northern Antofagasta province | ||

| Parent company | SQM | ||

| Dates of operation | 1890–2016 | ||

| Predecessor | ACN&R, TCPP, SIT | ||

| Technical | |||

| Track gauge | 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) | ||

| Electrification | 1500 V DC | ||

| Track length | 227 km (141 mi) | ||

| No. of tracks | Single | ||

| Highest elevation | 1,454 m (4,770 ft) | ||

| |||

Its history was influenced primarily by two factors: the rise and fall of the Chilean nitrate industry in particular SQM and its predecessors, and the evolution of railway traction technology from steam to electric and diesel motive power.

Construction

The story of the railway began with the contract signed on 12 May 1883 between Edward Squire and the Chilean government. After the War of the Pacific, Chile had decided to reorganize the nitrate industry in the Toco plain. A key element of the concession was the construction of a railway between the plain and the port of Tocopilla.

A joint-stock company, the "Anglo-Chilian Nitrate & Railway Company, Limited" was founded in London, in 1886[1] with a capital of £1mio (equivalent to about £130mio in 2020 [2]). In October of that year, construction of the “Santa Isabel” saltpetre plant began; this was the planned terminus of the railway.

The railway was designed by William Stirling of Lima, a son of the famous Robert Stirling, and a detailed description of the initial operation of the railway was published by his brother Robert in 1900.[3] Starting from the port, the line climbed steeply with a ruling gradient of 4.1% up the steep sides of the Barriles valley until it reached the plains. In order to minimise works such as bridges, tunnels , cuttings and embankments, and thus the cost of construction, the alignment comprised a reverse and 211 curves with a minimum radius of only 55m . After reaching relatively level ground at the top of the escarpment (Barriles station), the line continued to climb with a gentle gradient up to Ojeda station (km 53) where it reached its maximum altitude of 1,495m, then descended to El Toco and Santa Isabel, at kilometer 88. Tracklaying was completed in March 1890, to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge and with 24 kg/m rails." Thousands of Chilean workers and former coolies of Peru, at a significant cost of human life had built what the engineer in charge Manuel Ossa Ruiz "one of the most daring railroads on the Pacific coast".

In addition to the difficult terrain, there was another significant issue for the operation of steam locomotives: the absence of fresh water. Sea water was tried but the rate of corrosion was untenable. Accordingly water had to be distilled from the sea or that of the river Loa (10x less solutes than seawater but still unusable). Thus two desalination plants were built, one at the Loa river, the other in the port of Tocopilla. They used vacuum distillation and were able to make 90t per day of fresh water each. A watering station at km16 (alt 660m) was supplied from Tocopilla, requiring 62bar at the pump. Water from the Loa plant was pumped to a 180t reservoir tank at the summit and two smaller intermediate tanks.[4]

Development

After the inauguration on 15 November 1890, other nitrate plants sprang up necessitating the construction of additional branches: in 1895 to "Peregrina" and “Santa Fe” (passing through “Buena Esperanza” and “Iberia”). Further plants were built along these lines. In 1910, Anglo-Chilean started to build the Coya plant and a 31 km branch for El Toco to serve it.

In 1899 the railway transported 215,000 tons of cargo and 20,000 passengers, increasing to 308,000 tons and 45,000 in 1909. In 1902 the value of the railway was almost half the total value of the company.

In 1900 a passenger service ran twice per week between Tocopilla and El Toco. The journey was timed at 5 1/2h up and 5h 10 minutes down. After the construction of more plants, passenger services increased to a twice weekly service each to Santa Isabel and Santa Fe.

On 24 December 1924, the “Anglo-Chilean Consolidated Nitrate Corporation” (ACCNC), a company set up under Delaware law by the Guggenheim Brothers to take control of the Tocopilla nitrate and railroad company, with the intention of installing at large scale its new nitrate process.[5] The properties of the British company passed into its possession on 1 January 1925.

The construction of the mechanized plant "Coya Norte" (known as "María Elena" since 1927) necessitated a new branch, which starting just below the Central station. The branch had several intermediate stations of Tigre, Central (new) Colupito, Cerrillos, Tupiza and María Elena. In 1930 the line was extended to the south when the construction of the “Pedro de Valdivia” plant began. The 116 km María Elena - Pedro de Valdivia branch reaches became the main line; in the 1930s the railroad carried over one million tons. At the Miraje station a connection was made to the Longitudinal Railway.[6]

After the growth phase driven by growth of the nitrate industry came the decline until the end in 2016. The closure of the Shanks-process works in 1958 led to the closure of the Tigre-Santa Fe line, whose rails had been lifted by 1975.

The company operated Kitson-Meyer articulated locomotives on the steep section between Tocopilla and Barriles and Mallet semi-articulated locomotives for the plains sections. In 1927 the new owners replaced the Kitson-Meyer locomotives on the Tocopilla-Tigre route, electrifying it and putting into service seven General Electric 'Boxcab' locomotives of 67 tons, which ran at 12 km/h. 33-ton electric locos (known as los patos or “ducks”) were tasked to transport caliche from the mine to the processing plants.

In 1958 new General Electric diesel-electric locomotives began to arrive, destined to replace the 43 steam locomotives then in service. In January of that year, three 87t 1,320 hp locos with 43,000 lb tractive force nicknamed 'Giants of the pampas' at a cost of $165,000 each. Later 8 more smaller (73t) locomotives were received for service at the mines. In the same period 66t electric locos nicknamed 'geese' also destined for mine service; they replaced the last steam locos. In 1996, disused 'geese' were still to be seen at the old María Elena Powder Plant which had become a veritable railway graveyard.

In the 1990s the electrification between Barriles and Tigre was eliminated, and the 1958 “giants” took over traction duties.

When the Chilean nitrate industry was reorganised with the formation of SQM, the railway became part of that company. In 2008 SQM reported that per year, the railway transported 1.1 million tons of finished product to the port of Tocopilla and 12 million tons of caliche ore from various mining sites to the Pedro de Valdivia plant, and that it intended to invest $12mio in infrastructure improvements in 2009.[7]

Closure

In August 2015 unprecedented flash flooding caused numerous washouts on the electric section of the railroad, most notably the area around the switchback on the escarpment leading down to the port at Tocopilla. As a result of this, along with the declining prospects for nitrate, the railroad ceased all operations, both electric and diesel, in late November 2015. All railroad staff were laid off and all railroad equipment stored at Tocopilla and Maria Elena awaiting possible sale or scrapping. After 125 years of operation the railway was closed. Trucks are now hauling product from María Elena plant to the port.[8]

Locomotives of the Tocopilla nitrate railway

Initially the motive power was provided by steam. In the 1920s came electric traction up the escarpment thus reducing the need for fresh water. There was a separate electrified section between María Elena. Dieselization on the plains was done in the 1950s and in 1957 steam was finally phased out. Initially the locos were liveried in FCNR or FCN & R green, then FCTT brown, then SIT then finally SQM green and white. Nos. 30-32 and 501-54 are among the earliest examples of tri-mode locomotives. In addition to purchasing locomotives new or second hand, there were conversion of diesel to electric and electric to diesel, locomotives made by combining parts of other defunct locomotives, which do not all feature in the list below.

| Image | Manufacturer | Wheels | No. In class | ACN&R/FCTT/SIT/SQM Numbers | Years introduced | Years withdrawn | Power | weight | Model | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steam Locomotives 1890 - 1959 | |||||||||||

| Kitson & Co. | steam | 4-8-4T | 3 | 1,2,4 | 1890 | 1959 | mainline-plains | ||||

| Manning Wardle | steam | 0-6-4T | 1 | 5 | 1890 | 1890 | Named "Edward Squire" | ||||

| Manning Wardle | steam | 0-4-0 | 2 | 6,7 | 1890 | 1959 | shunting. No. 7 powered the inaugural train with President Jose Manuel Balmaceda aboard. As of 2010, preserved in Tocopilla.[9] | ||||

| Yorkshire Engine Co. | steam | 0-6+6-0T | 2 | 8,9 | 1891 | 1959 | Fairlie design, first used on the escarpment, but sent up to the plains | ||||

| Kitson & Co. | steam | 0-6+6-0T | 3 | 10,11,12 | 1894-5 | 1959 | Meyer type | ||||

| Kitson & Co. | steam | 2-6-2T | 3 | 13,14,15 | 1894-5 | 1959 | mostly for shunting at Tocopilla | ||||

| Kitson & Co. | steam | 0-4-2T | 4 | 16,17,27,28 | 1900,1910 | 1959 | |||||

| Kitson & Co. | steam | 4-8-4T | 2 | 18,19 | 1902 | 1959 | |||||

| Kitson & Co. | steam | 2-6-2T | 2 | 20,22 | 1903,1905 | 1959 | |||||

| Kerr Stuart & Co. | steam | 0-6+6-0T | 1 | 21 | 1903 | Meyer [10] | |||||

| Kitson & Co. | steam | 0-6+6-0T | 4 | 23-26 | 1903,1909 | 1959 | Meyer | ||||

| Kitson & Co. | steam | 2-6+6-2T | 4 | 29,30,36,37 | 1905, 1912 | 1959 | Meyer | ||||

| Electric Locomotives 1927-2016 | |||||||||||

| GE | electric | BoBo | 601-607 | 1927 | 2016 | 970 | mainline-escarpment. 602 wrecked in the '90s[11] | |||

| GE | electric | BoBo | 9 | 1-9 | 1942 | 40 | es:Oficina salitrera Pedro de Valdivia (PdV), formerly at Victoria works | ||||

| GE | electric (battery and overhead) | BoBo | 52 | 1-26, 32-58, 127-129 | 1927,1930 | 30 | 1-26(originally 101-126),127-129 at María Elena, 33-58(originally 4000-4025) at PdV. Two of these had diesel range extenders added and were renumbered 81 and 82. | ||||

| GE | electric (battery and overhead) and diesel | BoBo | 3 | 30-32 | 1930 | 30 | María Elena. First examples of trimode overhead electric, battery and diesel propulsion locos | ||||

| GE | electric (battery and overhead) and diesel | BoBo | 4 | 501-504 | 1930 | 35 | PdV. First examples of trimode overhead electric, battery and diesel propulsion locos | ||||

| Nippon Yusoki | electric (battery and overhead) | BoBo | 10 | 70-79 | 1975 | 41.3 | EBL-35 | PdV and María Elena. No. 74 out of service by 1992 | |||

| Baldwin Westinghouse | electric (battery and overhead) | BoBo | 6 | 90-94,96,97 | 1953 | 30 | PdV and María Elena. ex- standard gauge Denver tramways 1108-1111, . Nos. 96,97 had 5t of batteries added. Built in 1923 | ||||

| GE | electric | BoBo | 3 | 301-303 | 1975 | 2003 | 60 | PdV and María Elena mines. ex Hanna Mining standard gauge nos. 301-303 | |||

| Whitcomb Westinghouse | electric | BoBo | 3 | ME1-3 | 1950 | 1990 | 66 | PdV - María Elena. | |||

| GE | BoBo | 3 | PV1-3 | 1948 | 1990 | 66 | PdV and María Elena. PV2 and 3 were severely damaged in a collision but their remains were combined with ex Codelco 802 and 804 to make a pair of working locos | ||||

| GE | electric | CoCo | 4 | PV4-7 | 1958-60 | 1990 | 90 | PdV and María Elena. subsequently renumbered 7-10 | |||

| Chesta Ingenieria and Casagrande Motori | electric | BoBo | 6 | 651-656 | 2009-2011 | 2016 | 1200[12] | mainline-escarpment. Chile's first domestically manufactured locomotives | ||

| Diesel Locomotives 1950s - 2016 | |||||||||||

| GE | diesel | CoCo | 1 | 1 | 1978 | 104DE5 | ex-CN | |||

| GE | diesel | CoCo | 3 | 2-4 | 1958 | 2016 | 1420 | 90 | U12C | No 4 wrecked in 1987 | |

| GE | diesel | CoCo | 8 | 11-18 | 1958 | 2016 | 1420 | 73 | U12C | 11-13 and 18 wrecked or out service by 1992 | |

| GE | diesel | BoBo | 1 | 19 | 640 | U6B | ex-CAPSA metre gauge | ||||

| GM-EMD | diesel | A1A-A1A | 5 | 20-24 | 1986 | 1994 | 1200 | SW1200M | ex CODELCO standard gauge BoBo. 1 Wrecked between 1991 and 1994 | |

| GM-EMD | diesel | 937 | GR12UM | |||||||

| GE | diesel | CoCo | 4-5 | U20C | ex South African U20C rebuilt by Casagrande Motori, Santiago[13] |

Sources: Beroiza,[9] Macuer Llaña,[14] Binns[15] and Moroni and Rodríguez[16]

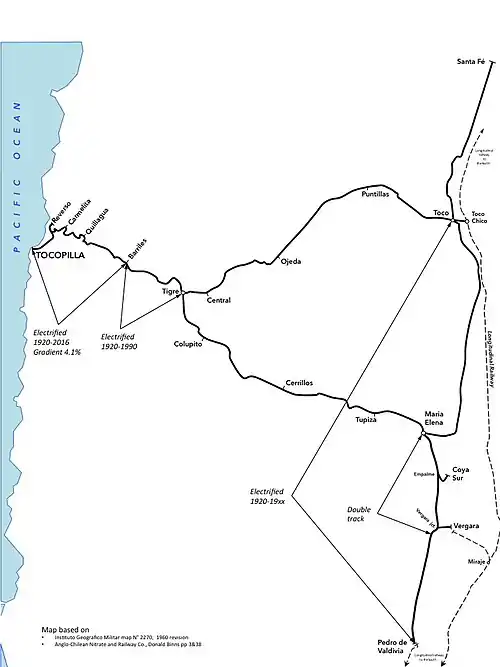

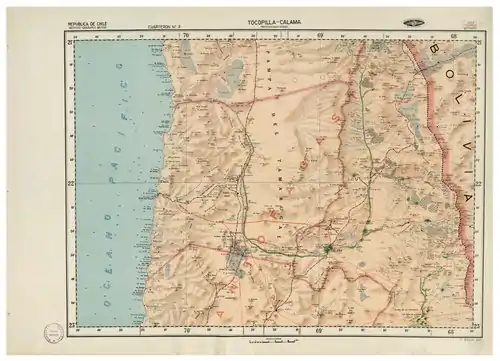

Maps

Scale map of the network

1945 Chilean Ordnance Survey map

Gallery

Barriles station

Barriles station GE 289A "Boxcab" engines built in the 1920s

GE 289A "Boxcab" engines built in the 1920s Driver's cab of GE 289A "Boxcab" SQM207 from 1927

Driver's cab of GE 289A "Boxcab" SQM207 from 1927 GE U20C arriving at Barriles

GE U20C arriving at Barriles SQM E651 and E653 are pulling an empty train towards Tocopilla

SQM E651 and E653 are pulling an empty train towards Tocopilla GE U20C shunting at Barriles

GE U20C shunting at Barriles E651 and E653 at Barriles station where electric and diesel traction exchanged

E651 and E653 at Barriles station where electric and diesel traction exchanged The driver's cab of the SQM locomotive E651 built in 2009

The driver's cab of the SQM locomotive E651 built in 2009

Bibliography

- "Anglo-Chilean Nitrate and Railway Co.", Donald Binns, Trackside Publications North Yorkshire, 1995. ISBN 1900095025.

- "Railways of the Andes", Bryan Fawcett, Allan & Unwin 1963. ISBN 978-0043850190

and in Spanish

- “Jeografía Descriptiva de la República de Chile”, Enrique Espinoza, 1903.

- “Los Tiempos” de Tocopilla newspaper, 7 Oct 1900 and 24 Jul 1906 issues.

- "Los ferrocarriles de Chile", Santiago Marín Vicuña, in "Chile en 1908", Eduardo Poirier (Editor)

- “La Industria del Salitre en Chile”. Semper y Michels, additional material by Javier Gandarillas and Orlando Ghigliotto, 1908.

- “Pampa” magazine, no. 118, Jan 1958.

- “Historia del Salitre, desde la Guerra del Pacífico hasta la Revolución de 1891”. Oscar Bermúdez, Santiago: Ediciones Pampa Desnuda, 1984.

- “Salitre, harina de luna llena”, Ana Victoria Durruty, NorPrint, Antofagasta (1993)

- "Red Norte, la historia de los ferrocarriles del norte chileno" Thompson, Ian; (Instituto de Ingenieros de Chile), 2003

References

- Hunter, Gilbert Macintyre (1894). "The Anglo-Chilian Nitrate Railway, Tocopilla to Toco". Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. 115: 326–331. doi:10.1680/imotp.1894.20112.

- https://www.in2013dollars.com/uk/inflation/1888 online calculator for long term inflation

- Stirling, Robert (1900). "The Tocopilla Railway". Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. 142 (1900): 89–102. doi:10.1680/imotp.1900.18720.

- Stirling, Robert (1900). "The Tocopilla Railway". Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. 142 (1900): 95–97. doi:10.1680/imotp.1900.18720.

- Macuer Llaña, Horacio (1930). Manual práctico de los trabajos en la Pampa Salitrera (in Spanish). Valparaiso: Talleres Gráficos Salesianos. pp. 193–221.

- Longitudinal Norte

- "SQM Annual Report 2008" (PDF). SQM. SQM. p. 16. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- "SQM Annual Report 2016" (PDF). SQM. SQM. p. 52. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- "Ferrocarril de Tocopilla al Toco: Locomotoras a Vapor". 25 September 2010.

- Kerr, Stuart and Company: Custom built designs

- "Ferrocarril de Tocopilla al Toco: Locomotoras Electricas". 25 September 2010.

- "Fabricación Locomotora Electrica 1200 HP". Chesta ingéniera (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ""Barriles"". Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Macuer Llaña, Horacio (1930). Manual práctico de los trabajos en la Pampa Salitrera (in Spanish). Valparaiso: Talleres Gráficos Salesianos.

- Binns, Donald (1995). Anglo-Chilean Nitrate and Railway Co. North Yorkshire: Trackside Publications. p. 34. ISBN 1900095025.

- Raúl Moroni and Mauricio Rodríguez. "María Elena and Pedro de Valdivia Electric Locomotive List". Narrow Gauge Electric Locomotives in Chile. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

See also

- FERROCARRIL DE TOCOPILLA AL TOCO Historical record of the railway with many illustrations (in Spanish)

- Espejo Leupín, Patricio Espejo Leupín (2017). "Historia del FC de Tocopilla al Toco". Amigos del Tren (in Spanish). Ernesto Vargas Cádiz. Retrieved 29 October 2020. Illustrated history of the line (in Spanish)

- Ferrocarril Salitrero de Tarapacá WP page on the network of nitrate railways to the North of Tocopilla (in Spanish)

- http://www.locopage.net/ge-expt-lst.doc 'Phil's page, a list of exported GE locomotives

- "Narrow Gauge Electric Locomotives in Chile" website (Raúl Moroni y Mauricio Rodríguez). Tocopilla - Tigre section and María Elena - Pedro de Valdivia section This site has the best map of the railway (Instituto Geográfico Militar, 1972)