Maria McAuley

Maria McAuley (née Fahy; 1847 – September 19, 1919), later Maria Gilbert, was an American missioner who, along with her husband Jerry McAuley, founded the McAuley Water Street Mission (now the New York City Rescue Mission) to shelter the poor of New York City who were primarily immigrants.[1][2] The couple were Irish Catholics immigrants who became Protestants and missioners after being saved from a lifestyle of drinking and crime by missionaries. McAuley Mission became the first of over 300 rescue missions in the United States; together, these form the Association of Gospel Rescue Missions.[2][3][4] Her second husband was noted New York City architect Bradford Gilbert.[5]

Maria McAuley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Maria Fahy 1847 |

| Died | September 19, 1919 (aged 71–72) Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Burial place | Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) |

| Known for | Co-founder of the New York City Rescue Mission |

| Spouse(s) | Jerry McAuley Bradford Gilbert |

Background

Maria Fahy was born in Ireland in 1847 and was raised in the Roman Catholic faith.[6][7][8] When she was a young child, she immigrated to the United States with her parents and lived in Massachusetts.[9] She attended school and a Protestant Sunday school.[9] However, her mother died when she was young and her father left, forcing Fahy to work to support herself.[10]

Fahy moved to New York City and became a waitress and entertainer in the Fourth Ward, a notorious area of Manhattan.[9] Some sources say she became a prostitute or "fallen woman".[11][12] She admitted to being "a drunkard in a Cherry Street hovel, with only straw for a bed."[13] Another time, she stated, "There was never a more degraded sinner than I was, to my shame it be said. My home was a drunkard's hovel, and the principal thing there was the rum bottle."[14]

.jpg.webp)

Around 1864, Fahey met and became romantically involved with the 25-year-old Jerry McAuley.[9][15] McAuley a self-proclaimed drunkard, and "river thief" who had just served seven years in Sing Sing prison; he received early parale from the fifteen-year sentence he received when he was nineteen years old.[16][7][15] The couple lived together on Cherry Street with another couple who shared their interest in drinking heavily.[9] McAuley returned to crime, becoming a fence, smuggler, and thief.[17]

In 1868, Water Street missionaries converted the Catholic McAuley to Protestantism; he had previously expressed an interest in a missionary's teachings while in prison.[16][7][17] McAuley invited Fahy to the John Allen MIssion and convinced her to give up alcohol.[8] She moved from the Cherry Street home she shared with McAuley and lived in a mission for women.[9] After several months of attending worship and Bible study at the mission, she moved to the New Jersey countryside to live with a Christian family who helped her rediscover religion and set aside her wayward lifestyle.[18][19][20] Apparently her relocation to New Jersey was, in part, an effort of the missionaries to separate Fahey from McAuley, after learning that the cohabitating couple was not married.[20] It also removed Fahey from the city's many temptations.[10]

After her conversion to a religious lifestyle, Fahey visited her father and lived with her older sister in New Bedford, Massachusetts.[20][21] During her absence from McAuley, she kept in touch by writing letters.[20] Fahey returned to New York City in 1872 after some Christian ladies hired her for missionary work.[19][3] She was a Bible reader and also provided testimony about her religious conversion in the Fourth Ward's saloons, tenement houses, and "dens of infamy".[19][22][9]

Fahy married McAuley in 1872.[6][7][23] Their marriage took place at the Howard Mission and Home for Little Wanderers, previously the Fourth Ward Mission, and was attended by a small group of friends.[20][12]

Missions

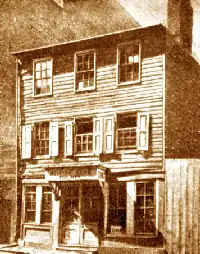

On October 8, 1872, the McAuleys founded the Helping Hand for Men, also called the McAuley Water Street Mission, in an old wooden house at 316 Water Street.[6][18][24][12][17] The mission house was surrounded by rum shops, dance halls, and gambling dens in an area that was frequented by drunkards, thieves, and prostitutes.[24] The purpose of the McAuley Mission was "to provide food, shelter, clothing and hope to people in crisis."[2] It provided free cots for sleeping, as well as bread and coffee.[9]

This mission held daily nondenominational public meetings at 7:30 p.m., along with services at 2:30 p.m. on Sundays.[25][26] According to a promotional booklet for the mission, its audience included homeless men and women, landsmen, sailors, strangers, the friendless, and anyone interested in Christian service.[25] The meetings lasted an hour and included Bible readings, singing of hymns, and testimonials by individuals who were saved from sin by the "power of Jesus".[25] Maria McAuley played the organ and also spoke to and shook the hands of each attendee after the meeting.[9] The mission did not collect money at its meetings.[25]

In 1882, the McAuleys opened the Jerry McAuley's Cremorne Mission at 104 West 32nd Street in Manhattan.[6][18] Maria McAuley ran the new mission, while Jerry continued to oversee the Water Street Mission.[9] The Cremorne Mission focused on helping women, especially prostitutes and other fallen women, turn their lives around.[27]

After her husband died in 1884, she carried on their work, serving as matron or superintendent of the Cremorne Mission.[28][6] The position paid $600 a year ($19,542 in today's money) and came with an apartment over the mission.[29] Perhaps due to managing the mission for eight years, her health began to fail and it was believed she would die in 1892.[6] On April 1, she resigned from her position with the mission and moved to Cranford, New Jersey.[29]

Later life

On May 12, 1892, Maria McAuley married noted New York architect Bradford Lee Gilbert in Cranford, New Jersey.[5] Gilbert was a long time supporter of Jerry McAuley's work and was a former trustee of the Cremorne Mission.[30][31] The two had courted for five years, and Gilbert married her after her health declined so that he could care for her.[5][6]

Their marriage was the conclusion of a national scandal.[31] In addition to their age difference—he was 38 and she was 55—he was married when they began courting.[32] In 1887, Gilbert separated from his socialite wife and filed for divorce in New Jersey.[13] On October 13, 1887, Cora Gilbert served her husband with divorce papers during the intermission of a prayer meeting at Cremorne Mission, based on infidelity.[13][33][34] At the same time, she served Maria with a $50,000 ($1,628,519 in today's money) lawsuit for alienation of affections, with allegations that "were numerous and specific."[13]

On October 16, 1887, at the Mission, Gilbert made a public announcement saying, "If it did not affect this mission and the noble Christian woman who conducts it, I would remain silent. I suppose you have all read in today's papers…a story reflecting upon Mrs. McAuley and myself. I pronounce it false. All those who know me will take my word, and all those who do not know me will see by the result that what I say is true."[35] Standing by Gilbert and McAuley were banker A. S Hatch, real estate agent Sidney Whittemore, Franklin W. Coe, and other ladies and gentlemen associated with McAuley Mission.[13] Hatch also spoke, saying "The very fact that I am on this platform tonight is sufficient for the purpose without saying a word, but I may add that my faith in Mrs. McAuley and Mr. Gilbert has not been shaken one jot by what has appeared in print, and I continue to have unwavering confidence in both."[13] McAuley also spoke briefly and "emphatically denied" the allegations.[36] In a few years, Gilbert obtained a divorce, and Cora Gilbert withdrew her lawsuit against McAuley.[37][32]

After their marriage, Maria and Bradford Gilbert lived at 225 Park Place in New York City and had a summer home in Accord, New York.[30] Neither continued an official association with Cremorne Mission.[29] They adopted their niece Blossom, daughter of her sister.[28] Bradford Gilbert died in 1911.[30] In 1919, Maria Fahy Gilbert died in her home at 585 Park Place in Brooklyn, New York.[6][7] Her funeral service was held at the Water Street Mission and she was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery.[6]

Legacy

The McAuley Water Street Mission was the first rescue mission in the United States and provided a template that was applied across the country and around the world.[38][12] It survives today as the New York City Rescue Mission, part of the The Bowery Mission.[38] The mission moved to its current location at 90 Lafayette Street in Tribeca in the 1960s.[38]

Maria McAuley is featured on a wayside educational marker on West 32nd Street in Manhattan, New York.[39]

References

- Magnuson, Norris; Magnuson, Beverly (9 November 2004). Salvation in the Slums: Evangelical Social Work 1865–1920. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-1-59244-997-2.

- Nasprettodaily, Ernie (4 October 2007). "135th anniversary for New York City Rescue Mission". NY Daily News. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Jerry McAuley". Citygate Network. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- Yates, Rowdy (2010). Tackling Addiction: Pathways to Recovery. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-1-84905-017-3.

- "Pertinent Paragraphs". The Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey). May 13, 1892. p. 3. Retrieved February 12, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Maria Fahy Gilbert, Mission Work, Dead". The Standard Union (Brooklyn, New York). September 20, 1919. p. 10. Retrieved February 12, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mrs. Maria F. Gilbert Dies". The New York Times. September 20, 1919. p. 11. Retrieved February 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- McAuley, Jeremiah; Offord, Robert Marshall (1885). Jerry McAuley: his life and work. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. New York: New York Observer. p. 43 – via Internet Archive.

- "Maria McAuley". The Bowery Mission. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- Offord, R. M. (Robert Marshall) (1907). Jerry McAuley: an apostle to the lost. New York: American Tract Society. p. 43 – via Internet Archive.

- Kurian, George Thomas and Lamport, Mark A. (2016). "Jeremiah 'Jerry' McAuley Encyclopedia of Christianity in the United States. Vol. 5. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 1446. ISBN 978-1-4422-4432-0.

- "Jerry McAuley, Ex-Inmate of Tombs & Sing Sing, Rescue Mission Pioneer". New York CorrectionHistory Society. March 17, 2005. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- "Mrs. McAuley Denies It: The Scandal Which Hovers over McAuley Mission". The New York Times. October 17, 1887. p. 17. Retrieved February 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bliss, William R. (March 1880). Down in Water St. every evening (2nd ed.). New York: The McAuley Water-Street Mission. p. 27.

- "Jerry McAuley". The Bowery Mission. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- Pierson, Arthur Tappan (1887). Evangelistic Work in Principle and Practice. Baker & Taylor. p. 289.

- Geoghegan, Patrick M. (October 2009). "McAuley, Jeremiah ('Jerry')". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- "Jeremiah McAuley". Dictionary of American Biography. New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1936.

- McAuley, Jeremiah; Offord, Robert Marshall (1885). Jerry McAuley : his life and work. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. New York : New York Observer. p. 44 – via Internet Archive.

- McAuley, Jeremiah; Offord, Robert Marshall (1885). Jerry McAuley : his life and work. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. New York : New York Observer. pp. 162–163 – via Internet Archive.

- Offord, R. M. (Robert Marshall) (1907). Jerry McAuley: an apostle to the lost. New York: American Tract Society. p. 162 – via Internet Archive.

- Offord, R. M. (Robert Marshall) (1907). Jerry McAuley : an apostle to the lost. New York : American Tract Society. p. 44 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Life and Ministry of Jerry McAuley". Citygate Network. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- Bliss, William R. (March 1880). Down in Water St. every evening (2nd ed.). New York: The McAuley Water-Street Mission. p. 8.

- Bliss, William R. (March 1880). Down in Water St. every evening (2nd ed.). New York: The McAuley Water-Street Mission. p. back cover

- Offord, R. M. (Robert Marshall) (1907). Jerry McAuley: an apostle to the lost. New York: American Tract Society. p. 45 – via Internet Archive.

- "A Former Thief Dedicates His Life to the City's Poor". Ephemeral New York. October 13, 2014. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

- "Bradford Lee Gilbert pt 2". The Standard Union (Brooklyn, New York). September 2, 1911. p. 2. Retrieved February 12, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mrs. Gilbert Now". The New York Times. May 13, 1892. p. 3. Retrieved February 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bradford Lee Gilbert pt 1". The Standard Union (Brookyn, New York). September 1, 1911. p. 2. Retrieved February 12, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Grey, Christopher (July 1, 2007). "The Architect Who Turned A Railroad Bridge on Its Head". The New York Times – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- "Joined Their Fortunes". St Louis Post-Dispatch. May 13, 1892. p. 8. Retrieved February 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "While a Prayer Meeting Was in Progress". Hartford Courant (Hartford, CT). October 17, 1887. p. 1. Retrieved February 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Sued for Divorce: The Widow of Jerry McAuley Made Correspondant". San Francisco Chronicle. October 17, 1887. p. 1. Retrieved February 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Exhorter Gilbert Denies It". The Sun (New York, NY). October 17, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved February 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mrs. McAuley Denies It: The Scandal Which Hovers over McAuley Mission". The New York Times. October 17, 1887. p. 17. Retrieved February 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Gray, Christopher (July 1, 2007). "The Architect Who Turned A Railroad Bridge on Its Head". The New York Times. p. 2 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- "A legacy of love: Looking back 150 years". The Bowery Mission: Updates. 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- "Jerry McAuley's Mission Historical Marker". The Historical Market Database. August 12, 2023. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

External links

- New York City Rescue Mission - Water Street mission today