Mary of Hungary (governor of the Netherlands)

Mary of Austria (15 September 1505 – 18 October 1558), also known as Mary of Hungary, was queen of Hungary and Bohemia[note 2] as the wife of King Louis II, and was later governor of the Habsburg Netherlands.

| Mary of Austria | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Hans Maler zu Schwaz c. 1520 | |

| Queen consort of Hungary and Bohemia | |

| Tenure | 13 March 1516 – 29 August 1526 |

| Coronation | 11 December 1521 (Hungary) 1 June 1522 (Bohemia) |

| Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands | |

| In office 28 January 1531 – 25 October 1555 | |

| Monarch | Charles V |

| Predecessor | Margaret of Austria |

| Successor | Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy |

| Born | 15 September 1505 Brussels, Netherlands |

| Died | 18 October 1558 (aged 53) Cigales, Spain |

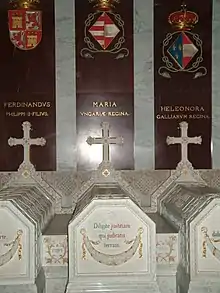

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Philip I of Castile |

| Mother | Joanna of Castile |

| Religion | Christianity (Catholicism)[note 1] |

| Signature |  |

The daughter of Queen Joanna and King Philip I of Castile, Mary married King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia in 1515. Their marriage was happy but short and childless. Upon her husband's death following the Battle of Mohács in 1526, Queen Mary governed Hungary as regent in the name of the new king, her brother, Ferdinand I.

Following the death of their aunt Margaret in 1530, Mary was asked by her eldest brother, Emperor Charles V, to assume the governance of the Netherlands and guardianship over their nieces, Dorothea and Christina of Denmark. As governor of the Netherlands, Mary faced riots and a difficult relationship with the Emperor. Throughout her tenure she continuously attempted to ensure peace between the Emperor and the King of France. Although she never enjoyed governing and asked for permission to resign several times, the Queen succeeded in creating a unity between the provinces, as well as in securing for them a measure of independence from both France and the Holy Roman Empire.[1] After her final resignation, the very frail Queen moved to Castile, where she died.

Early life

Born in Brussels on 15 September 1505, between ten and eleven in the morning, Archduchess Mary of Austria was the fifth child of King Philip I and Queen Joanna of Castile. Her birth was very difficult; the Queen's life was in danger and it took her a month to recover. On 20 September, she was baptized by Nicolas Le Ruistre, Bishop of Arras, and named after her paternal grandmother, Mary of Burgundy, who had died in 1482. Her godfather was her paternal grandfather, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I.[2]

On 17 March 1506, Emperor Maximilian promised to marry her to the first son of King Vladislaus II of Hungary. At the same time, the two monarchs decided that a brother of Mary would marry Vladislaus' daughter Anne. Three months later, Vladislaus' wife, Anne of Foix-Candale, had a son, Louis Jagiellon. Queen Anne died and the royal physicians made great efforts to keep the sickly Louis alive.[3]

After the death of Mary's father in September 1506, her mother's mental health began to deteriorate. Mary, along with her brother, Archduke Charles, and her sisters, Archduchesses Eleanor and Isabella, was put into the care of her paternal aunt, Archduchess Margaret, while two other siblings, Archduke Ferdinand and posthumously-born Archduchess Catherine, remained in Castile. Mary, Isabella, and Eleanor were educated together at their aunt's court in Mechelen. Their music teacher was Henry Bredemers.[4][5][6]

Queen of Hungary and Bohemia

Mary was summoned to the court of her grandfather Maximilian in 1514.[5] On 22 July 1515, Mary and Louis were married in St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna. At the same time, Louis' sister Anne was betrothed to an as yet unspecified brother of Mary, with Emperor Maximilian acting as proxy.[3] Due to their age, it was decided that the newly married couple would not live together for a few more years.[3][5]

Anne eventually married Mary's brother Ferdinand and came to Vienna, where the double sisters-in-law were educated together until 1516. That year, Mary's father-in-law died, making Louis and Mary king and queen of Hungary and Bohemia. Mary moved to Innsbruck, where she was educated until 1521. Anna and Mary moved first to Vienna, and then to Innsbruck. Maximilian rarely visited, but he sent his hunter home to instruct the two girls in the art of hunting. There was emphasis on their ablities to handle weapons and other physical skills. The Humanist education they enjoyed focused on problem-solving skills. They were also instructed in dancing, music, and came in contact with many humanists who visited the imperial library there. Innsbruck was also home to a great weapon arsenal and a growing armament industry built by the emperor.

This was her forming period. Similar to her grandfather Maximilian in many respects (she did not have his lively personality, but proved a better manager of financial affairs), Mary displayed a natural inquistive mind and developed interest in the practical aspects of governing as well as military affairs.[7] This passion would later be demonstrated during her tenure as governor of the Netherlands.[5]

Life with Louis

Mary travelled to Hungary in June 1521, two and a half years after Emperor Maximilian's death. She was anointed and crowned queen of Hungary by Simon Erdődy, Bishop of Zagreb, in Székesfehérvár on 11 December 1521. The queen's coronation was followed by brilliant festivities. The royal marriage was blessed on 13 January 1522 in Buda. Mary's anointment and coronation as queen of Bohemia took place on 1 June 1522.[5][8]

Mary and Louis fell in love when they were reunited.[3] At first, Queen Mary had no influence over politics of Hungary and Bohemia because of her youth. Her court was replete with Germans and Dutch, who formed a base for the interests of the House of Habsburg. By 1524 Mary negotiated significant authority and influence for herself. In 1525, she took control over one powerful political faction and neutralised another.[9] Austria's ambassador, Andrea de Borgo, was appointed by the Queen herself.[5]

During her tenure as queen of Hungary, Mary attracted the interest of Martin Luther, who dedicated four psalms to her in 1526. Despite her brother Ferdinand's strong disapproval, Luther's teachings held great appeal for Mary during her marriage and even more for her sister Isabella and her brother-in-law King Christian II of Denmark. Mary turned away from his teachings mostly because of pressure from Ferdinand. Her trusted court preacher, Johann Henckel, is also considered responsible for Mary's return to orthodox Catholicism. The return was lukewarm,[10] but historian Helmut Georg Koenigsberger considers Mary's reputation for sympathy with Lutheranism to be "much-exaggerated".[4]

Louis and Mary spent their free time riding and hunting in the open country near the palace. They tried unsuccessfully to mobilize the Hungarian nobility against the imminent Ottoman invasion. Mary tried to cooperate with her brother Ferdinand in organizing a Hungarian defence against the Ottoman Empire, while at the same time consolidating Habsburg influence. She was much more vigorous and spiritually stronger than Louis – the Hungarians realized this themselves and criticized their king – but the fact she relied on non-Hungarian advisors costed her sympathy. Alfred Kohler opines that their defence project failed because of Louis's lack of competence.[11][12]

Louis had inherited the crown of a country whose noblemen were fighting among themselves and against the peasantry. Hungary was deeply divided when, by the end of 1525, it became clear that the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I was planning to invade.[3]

Ottoman invasion

| "If she [Mary] could only be changed into a king, our affairs would be in better shape." |

| A letter of a Hungarian courtier to Desiderius Erasmus[9] |

| "The most serene queen is about twenty-two years old, of diminutive stature, long and narrow face, rather comely, very spare, with a slight colour, black eyes, her under lip rather thick, lively, never quiet either at home or abroad." |

| A description of Mary recorded by the Venetian ambassador at the Hungarian court[9] |

On 29 August 1526, Suleiman and his army broke through Hungary's southern defences. Louis and his entire government marched out with a small army of 20,000 men. The Battle of Mohács was over in less than two hours, with the entire Hungarian army virtually annihilated. Louis tried to flee the site of the battle but slipped from his frightened horse and drowned. Mary would mourn him for the rest of her life.[10]

Hungary was divided into three parts: Ottoman Hungary – a part of the Ottoman Empire, Royal Hungary – ruled by Mary's brother Ferdinand, and Eastern Hungarian Kingdom – ruled by John Zápolya. Ferdinand was elected King of Bohemia. Mary took a vow to never remarry and always wore the heart-shaped medallion worn by her husband in the fatal Battle of Mohács.[10][13][14]

Regency in Hungary

The day after her husband's death, Mary notified Ferdinand of the defeat and asked him to come to Hungary. She requested troops to support her until his arrival. Ferdinand, busy in Bohemia where he had already been elected king, instead named Mary his regent in Hungary.[15]

Mary spent the following year working to secure the election of Ferdinand as King of Hungary. On 14 February 1527, she asked for his permission to resign as regent. Permission was denied, and Mary had to remain in the post until the summer of 1527, when Ferdinand finally came to Hungary and assumed the crown, to Mary's relief.[15]

Mary soon experienced financial troubles, illnesses, and loneliness. In 1528, her aunt Margaret suggested that she should marry King James V of Scotland. Mary rejected the idea because she had loved her husband and did not wish another marriage. In 1530 Charles again suggested that she should remarry; he proposed to arrange a marriage to Frederick of Bavaria, who had unsuccessfully courted Mary's sister Eleanor sixteen years before. Mary rejected him as well.[15]

Ferdinand offered Mary the post of regent again in 1528, but she declined, saying that "such affairs need a person wiser and older".[15] Ferdinand persisted in drawing Mary into his affairs throughout 1529. Archduchess Margaret died on 1 December the next year, leaving the position of Governor of the Seventeen Provinces in the Netherlands vacant. Ferdinand informed her about their aunt's death, saying that her affairs might now "take a different course".[15]

Governor of the Netherlands

On 3 January 1531, Mary's older brother, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, requested that she assume the regency of the Netherlands. Charles was ruling a vast empire and was constantly in need of reliable family members who could govern his remote territories in his name. Mary reluctantly accepted on Charles' insistence.[10] On 6 October 1537, in Monzón, the Emperor wrote to her:

I am only one and I can't be everywhere; and I must be where I ought to be and where I can, and often enough only where I can be and not where I would like to be; for one can't do more than one can do.[16]

Mary served as regent of the Netherlands so well that Charles forced her to retain the post and granted her more powers than their aunt had enjoyed.[17] Unlike her aunt, Mary was deeply unhappy during her tenure as governor and never enjoyed her role. In May 1531, having governed for only four months, Mary told her brother Ferdinand the experience was like having a rope around her neck.[4] While Margaret had been considered truly feminine, flexible, adaptable, humorous and charming, Mary was unyielding and authoritarian. Margaret accomplished her goals using a smile, a joke, or a word of praise, but Mary used cynical and biting comments. Unlike her aunt, Mary was unable to forgive or forget. She recognized this lack of "power as a woman" as her main problem.[18]

Guardianship over nieces

Assuming the regency in the Netherlands meant assuming the guardianship of her nieces, Dorothea and Christina of Denmark, the daughters of her older sister, Queen Isabella of Denmark, who had died in 1526. Upon Isabella's death, the princesses had been cared for by Archduchess Margaret. Charles now relied upon Mary to arrange marriages for them, especially for Dorothea, whom he wanted to place on the Danish throne.[19]

In 1532, Francesco II Sforza, Duke of Milan, proposed a marriage with Christina, who was then 11 years old. Charles agreed to the marriage and allowed its immediate consummation. Mary determinedly opposed this decision, explaining to Charles that Christina was too young for consummation of the marriage. Charles ignored her, but she nevertheless managed to delay the marriage. She first told the Milanese envoy that her niece was ill and then took her to another part of the Netherlands for "serious affairs". Christina was finally married on 28 September 1532, but Mary managed to postpone her departure until 11 March 1533.[19]

Immediately after Christina's departure, Mary fell ill and requested that she be allowed to resign as governor, but Charles did not allow it. A year later, Dorothea too was married. A few months after Dorothea's departure, the now widowed Christina returned to her aunt's court. King Henry VIII of England immediately proposed marriage to Christina, and Charles urged Mary to negotiate the marriage. She was not in favour of the union, and delayed. Henry VIII was excommunicated in 1539, at which point Charles had to end the negotiations.[19]

Relationship with Charles

The Emperor assured Mary that he had no doubts about her loyalty to the Catholic Church. He had learned that the Queen could not easily be bullied, especially not in matters which affected her personally.[4] Yet, upon leaving the States General in October 1531, Charles gave her a warning, saying that if his parent, wife, child or sibling became a follower of Luther, he would consider them his greatest enemy.[4] Mary was thus forced to suppress Protestantism in the Netherlands, regardless of her own religious tolerance. However, she always strived to enforce her brother's laws on religion as little as possible. She was accused of protecting Protestants on several occasions.[20]

Her determination sometimes caused clashes of wills with Charles. In most matters of patronage, Mary had to defer to Charles, which is why his relations in this area were not much better with Mary than with their aunt Margaret.[4] He often criticized her decisions, which negatively affected their otherwise affectionate relationship.[21]

Riots

| "Whoever is in charge of this country should be very sociable with everyone in order to gain the goodwill both of the nobility and the commonality; for this country does not render the obedience which is due to a monarchy, nor is there an oligarchical order nor even that of a republic. And thus a woman, especially if she is a widow, cannot do what should be done." |

| Mary to Charles on the occasion of his abdication as sovereign of the Netherlands. Brussels, 1555.[22] |

Mary became worried about losing authority and was having trouble with the finances in February 1534. She complained that the budget could not be balanced even during the times of peace. Charles assured her that she was doing her best.[23]

The Queen complained to Charles in August 1537 that the Low Countries were no longer governable and said he should come himself. In fact, Mary handled the crisis quite well and kept a cool head in public.[24] In October, she travelled to the north of France to meet her brother-in-law, King Francis I of France, the second husband of her sister Eleanor. On October 23, they signed a treaty. Francis thereby promised Mary that he would not help those who rebelled against her, while the Queen promised to compensate certain French noblemen who lost their land in the Low Countries during the Italian Wars.[25]

Military policies

In 1534, Mary prepared a proposal for a defensive union of all the provinces in her councils. She made the proposal at the States General in Mechelen in July, citing her brother, who had requested the provinces assist each other.[26] The plan had to be given up and, after Mary and Eleanor's failure to negotiate peace between the Empire and France, Mary's letters to Charles began to resemble the theatrical outbursts of their aunt Margaret.[23]

Mary strived for peace in the Netherlands. Charles paid no attention to the problems she was facing as governor and often ignored her warnings.[1] One such incident led to Charles's loss of the city of Metz to France.[27] Mary was forced to wage war against France in 1537 and to deal with the Revolt of Ghent between 1538 and 1540. Mary's appointment as Governor of the Netherlands was renewed on 14 October 1540, after the revolt in Ghent had been subdued.[1]

Defence of the Herring Fleet

During the last decade of her regency, Scottish privateers became a serious problem in the North Sea. A 1551 petition by Antwerp merchants to the Habsburg government claimed that Scottish pirates and others, over the course of eight to ten years, had taken ships and goods that were worth about 1,600,000 Holland pounds. In 1547, Mary summoned deputies from the three fishing provinces to debate the matter. Many were in favor of safe-conducts, supposedly cheaper and more effective than building up naval armaments, but the Queen refused to negotiate with a weak Scottish government. Despite a firm sentiment against money for warships, Mary acted resolutely and issued orders forbidding all herring buses or merchantmen from sailing until the three fishing provinces could formulate an acceptable plan for naval defense. Under her pressure, the provinces agreed to create a common Netherlands war fleet, but differences were only completely worked out in the very last years of her government. Cornelis de Scepper, her chief naval strategist created a plan, according to which, a large naval squadron would patrol on station off the Estuary of Maas, while swift yachts would be responsible for communication with the herring fleet. Holland consented to provide eight warships for a fleet of twenty-five sail, intended to provide security for all branches of trade in the North Sea. James D.Tracy comments that "The development of this new strategy for naval defense was no small accomplishment, but most of the credit should go to the leadership provided by Mary of Hungary and her officials".[28]

Creation of a permanent navy

Mary, the Admiral Maximilian of Burgundy and the Councillor Cornelis de Schepper were the team behind the professionalization process that characterized the Low Countries' maritime policy in the 1550–1555 period. The central government led by Mary tried to make provinces recognize the authority of the Admiralty. Mary favoured de Schepper over Maximilian but there were no distrust between the two men and the three formed an excellent team. Maximilian had too much responsibilities in various provinces, so perhaps this was why he appreciated help from others. De Schepper played the role of the mastermind, who formulated every memorandum and document regarding naval policies. From 1550 to 1555 (the year he died), he was the equal of the Admiral in equipping warships and organizing convoys. During this period, Schepper's activities focused on Flanders while Maximilian focused on Holland and Zeeland (initially, his authority was only recognized in Zeeland and Flanders but as he also the Stadtholder of Holland, he was able to exercise this authority in this province too). Their efforts resulted in the creation of a permanent navy. Mary proved herself a pragmatic and energetic leader in the process.[29]

Resignation

The Queen had to mediate between her brothers in 1555, when Charles decided to abdicate as emperor and leave the government of the Netherlands to his son Philip, despite Ferdinand's objections. When Mary learned of Charles's decision, she informed him that she too would resign. Both Charles and Philip urged her to remain in the post, but she refused. She chronicled the difficulties she had faced due to her gender, the fact that she could not act as she thought she should have because of disagreements with Charles, and her age. Furthermore, she did not wish to accommodate to the ways of her nephew after years of getting used to Charles's demands.[30] The actual reason for Mary's resignation was her numerous disagreements with her nephew.[31] She asked for Charles's permission to leave the Netherlands upon her resignation, fearing that she would be drawn into politics again if she remained.[30]

Charles finally allowed his sister to resign. She formally announced her decision on 24 September 1555 and dismissed her household on 1 October. On 25 October, her authority was transferred to Philip,[30] who, despite his personal dislike of his aunt, tried to convince her to resume the post. After another quarrel with Philip, Mary retired to Turnhout.[32] She remained in the Netherlands one more year.[30]

Life in Castile

Mary wished to retire to Castile and live with her recently widowed sister Eleanor, near Charles, who had retired. She was afraid of moving to Castile because, although her mentally unstable mother Joanna (who died aged 75 in April 1555) had been sovereign there, Mary had never lived in Castile. She was afraid that Eleanor's death would leave her alone in a country whose customs she did not know. In the end, she decided to move to Castile, while retaining the possibility of moving back to the Netherlands in case she could not adjust to the Castilian customs. Charles, Eleanor, and Mary sailed from Ghent on 15 September 1556.[30]

Although she repeatedly assured her brother that she had no intention of occupying herself with the affairs of state, Mary offered to become adviser to her niece Joanna, who was serving as regent for Philip. Joanna did not wish to share power and declined her aunt's offer.[33][34]

Mary did not enjoy her retirement for long; Eleanor died in her arms in February 1558.[35] The grief-stricken queen travelled to Charles to ask him for advice about her future. Charles told her that he wanted her to resume regency in the Netherlands, and promised a home and a large income, but Mary declined the offer. Her nephew Philip then urged her advisor to convince her to return. When Charles became ill in August, Mary accepted the offer and decided that she would become governor once again.[36]

In September, Mary was fully prepared to depart for the Netherlands and resume her post when she was informed of Charles's death. Distressed by the death of another sibling, the Queen, who had suffered from a heart disease most of her life, had two heart attacks in October. Both were so severe that her doctors thought that she had died.[37][38] When Joanna visited her, Mary was still determined to fulfill the promise she had given to Charles and assume the regency in the Netherlands, but she was weak and feverish.[39] She died only few weeks later, in Cigales on 18 October 1558.[36]

In her last will, Mary left all her possessions to Charles. Since Charles had died, Philip inherited his aunt's property. Shortly before her death, she decided that Philip and Joanna should execute her will.[40] She requested that her heart-shaped gold medallion, once worn by her husband, be melted down and the gold distributed to the poor.[41]

Queen Mary was first buried in the Monastery of Saint Benedict in Valladolid. Fifteen years after her death, Philip ordered that the remains be transferred to El Escorial.[40]

Patronage of arts

Mary was a keen art collector, and owned several important masterpieces of Early Netherlandish painting as well as more contemporary works. These included the Deposition of Christ by Rogier van der Weyden, now in the Museo de Prado, and the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck, now in the National Gallery, London. Most of the collection passed to the Spanish Royal Collection after her death.[42]

Queen Mary of Hungary was a great patron of music. She supported both sacred and secular music at her court in the Netherlands, where her maître de chapelle was Benedictus Appenzeller. Several elaborate music manuscripts that she commissioned during her governance are preserved in Spain in the monastery of Montserrat.[43]

Appearance and personality

According to Koenigsberger, having inherited the Habsburg lip and not very feminine looks, Mary was not considered physically attractive. Her portraits, letters, and comments by her contemporaries do not assign her the easy Burgundian charm possessed by her grandmother, Duchess Mary of Burgundy, and her aunt Margaret. Nevertheless, she proved to be a determined and skilful politician, as well as an enthusiastic patron of literature, music, and hunting.[4] The contemporary historian Pierre de Bourdeille though found her beautiful and charming, despite the slight tendency towards mannishness.[44] People close to her also found her charming.[45] What made her perceived as masculine (and usually attracted criticism as going beyond "acceptable female behavior") was "her authoritarian manner, her overly public life and her 'masculine' activities".[46]

Arms

- Heraldry of Mary of Hungary

Coat of arms used as Queen Consort

Coat of arms used as Queen Consort Coat of arms used as Dowager Queen

Coat of arms used as Dowager Queen

Notes

- Despite her interest in the teachings of Martin Luther, Mary never renounced Catholicism.

- Mary's full title during her tenure as governor of the Netherlands was: Mary, by the Grace of God, Queen of Hungary, of Bohemia, etc., governor of the Netherlands for His Imperial and Catholic Majesty, and his lieutenant.

References

Footnotes

- Jansen, 101.

- de Iongh, 16–17.

- O'Malley, 178.

- Koenigsberger, 125.

- Bietenholz, 399.

- Goss, 132 (Music in the Court Records of Mary of Hungary).

- Royen, Laetitia V. G. Gorter-Van (1995). Maria van Hongarije, regentes der Nederlanden: een politieke analyse op basis van haar regentschaps-ordonnanties en haar correspondentie met Karel V (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. pp. 41, 59–66, 79, 373. ISBN 978-90-6550-394-7. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- de Iongh, 72.

- Jansen, 98.

- O'Malley, 179.

- Hamann, Brigitte (1988). Die Habsburger: ein biographisches Lexikon (in German). Piper. p. 284. ISBN 978-3-492-03163-9. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- Kohler, Alfred (2003). Ferdinand I., 1503-1564: Fürst, König und Kaiser (in German). C.H.Beck. p. 110. ISBN 978-3-406-50278-1. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- Earenfight, 50.

- Cruz, 94.

- Jansen, 99.

- Koenigsberger, 123.

- Piret, 63.

- Jansen, 102, 104.

- Jansen, 100–101.

- Piret, 80.

- Koenigsberger, 136.

- Koenigsberger, 151.

- Koenigsberger, 137.

- Koenigsberger, 144.

- Knecht, 173.

- Koenigsberger, 130.

- Knecht, 215.

- Tracy, James D. (23 October 2018). Holland Under Habsburg Rule, 1506–1566: The Formation of a Body Politic. Univ of California Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-520-30403-1. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- Sicking, L. H. J. (1 January 2004). Neptune and the Netherlands: State, Economy, and War at Sea in the Renaissance. BRILL. pp. 482–484. ISBN 978-90-04-13850-6. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- Jansen, 103.

- Piret, 161–162.

- Piret, 163.

- Iongh, 282.

- Piret, 167.

- Piret, 166.

- Jansen, 104.

- de Iongh, 288.

- Piret, 168.

- de Iongh, 289.

- Piret, 171.

- de Iongh, 273–274.

- Wethey, 202.

- Goss, 132–173 (Music in the Court Records of Mary of Hungary).

- de), Pierre de Bourdeille Brantôme (seigneur (1908). Famous Women. A. L. Humphreys. p. 297. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- Doyle, Daniel Robert (1996). The Body of a Woman But the Heart and Stomach of a King: Mary of Hungary and the Exercise of Political Power in Early Modern Europe. University of Minnesota. p. 227. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- Doyle 1996, p. 227.

Bibliography

- Bietenholz, Peter G.; Deutscher, Thomas B. (2003). Contemporaries of Erasmus: a biographical register of the Renaissance and Reformation, Volumes 1–3. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8577-6.

- Cruz, Anne J.; Suzuki, Mihoko (2009). The Rule of Women in Early Modern Europe. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07616-9.

- Earenfight, Theresa (2005). Queenship and political power in medieval and early modern Spain. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-5074-X.

- Federinov, Bertrand et Gilles Docquier (eds), Marie de Hongrie. Politique et culture sous la Renaissance aux Pays-Bas (Mariemont 2009) (Monographies du Musée royal de Mariemont, 17).

- Fuchs, Martina und Orsolya Réthelyi (eds.), Maria von Ungarn (1505–1558). Eine Renaissancefürstin (Münster, Achendorff, 2007) (Geschichte in der Epoche Karls V., 8).

- Goss, Glenda (1984). Music in the Court Records of Mary of Hungary. University of North Carolina.

- de Iongh, Jane (1958). Mary of Hungary: second regent of the Netherlands. Norton.

- Jansen, Sharon L. (2002). The monstrous regiment of women: female rulers in early modern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-21341-7.

- Knecht, Robert Jean (2001). The rise and fall of Renaissance France, 1483–1610. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22729-6.

- Koenigsberger, Helmut Georg (2001). Monarchies, states generals and parliaments: the Netherlands in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80330-6.

- O'Malley, John W. (1988). Collected Works of Erasmus: Spiritualia. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2656-7.

- Piret, Etienne (2005). Marie de Hongrie. Jordan. ISBN 2-930359-34-X.

- Wethey, Harold (1969). The Paintings of Titian: The portraits. Phaidon.

Further reading

- Brand, Hanno (2007). The dynamics of economic culture in the North Sea and Baltic Region: in the late Middle Ages and early modern period. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 978-90-6550-882-9.

- Goss, Glenda (1975). Benedictus Appenzeller: Maître de la Chappelle to Mary of Hungary and Chansonnier. University of North Carolina.

- Goss, Glenda (1984). Mary of Hungary and Music Patronage (Sixteenth Century Journal). University of North Carolina.

- Réthelyi, Orsolya (2005). Mary of Hungary: the queen and her court, 1521–1531. Budapest History Museum. ISBN 963-9340-50-2.

- Sicking, Louis (2004). Neptune and the Netherlands: state, economy, and war at sea in the Renaissance. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13850-1.

- Woodfield, Ian (1988). The Early History of the Viol. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35743-8.

External links

Media related to Mary of Habsburg at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mary of Habsburg at Wikimedia Commons