Mariano Paredes (President of Mexico)

José Mariano Epifanio Paredes y Arrillaga (c. 7 January 1797 – 7 September 1849) was a Mexican conservative general who served as president of Mexico between December 1845 and July 1846. He assumed office through a coup against the liberal administration led by José Joaquín de Herrera. He was the grandfather of 38th Mexican President Pedro Lascuráin Paredes.[1]

Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga | |

|---|---|

| |

| 15th President of Mexico | |

| In office 31 December 1845 – 28 July 1846 | |

| Vice President | Nicolás Bravo |

| Preceded by | José Joaquín de Herrera |

| Succeeded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 7 January 1797 Mexico City, Viceroyalty of New Spain |

| Died | 7 September 1849 (Age 52) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican Spanish (prior to 1821) |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse | Josefa Cortés |

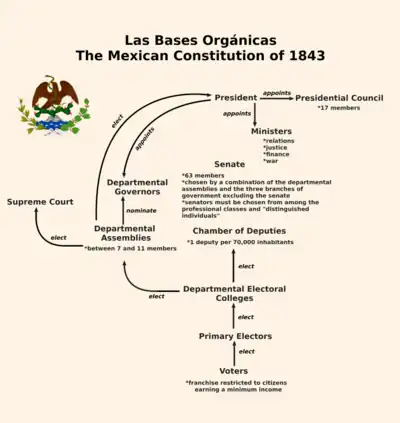

During the Centralist Republic of Mexico he led three successful coups against the Mexican government. In 1842, he led a movement to overthrow the presidency of Anastasio Bustamante over a financial crisis, which led to the drafting of a new constitution known as the Bases Orgánicas, promulgated on 14 June 1843. In 1844, he proclaimed a coup against Antonio López de Santa Anna which was joined by congress in protest against Santa Anna's unconstitutional acts. In 1845, he led a coup against President José Joaquín de Herrera over his intention to recognize Texan independence, where he assumed the presidency.

His administration dealt with the start of the Mexican–American War in April 1846. Before the conflict started, Paredes had expressed interest in establishing a monarchy in Mexico before abandoning the idea to focus on the war. Due to a series of military losses, Paredes faced the prospect of being overthrown and resigned on 28 July 1846. Historian Michael Costeloe described Paredes as "strongly proclerical, he believed that a liberal democracy and federal structure were inappropriate for Mexico in its then state of development, and that the country could be governed only by the army in alliance with the educated and affluent elite."[2]

Early life

Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga was born in Mexico in the year 1797 and began his military career as a cadet on 6 January 1812, during the Mexican War of Independence, initially fighting on the side of the Spanish loyalists. He was promoted to second lieutenant standard bearer in 1816 and in 1818 joined a company of grenadiers. He saw action twenty times when in March, 1821 his regiment switched sides and joined Agustín de Iturbide's Plan of Iguala. He joined in the battles that occurred prior to the Trigarantine Army's entrance into Mexico City. At Acámbaro Iturbide promoted him to captain of chasseurs. In the action at Arroyo Hondo, he formed part of the reconnoitering party made up thirty men and a few horses under the command of Epitacio Sanchez and they were able to hold off a superior Spanish force until Iturbide arrived with reinforcements and the Spaniards were repulsed. For his services at this battle Iturbide granted Paredes a coat of arms. He was present at San Luis de la Paz where seven hundred prisoners of war were taken and he took part in the siege and capture of Querétaro and Mexico City for which he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.[3]

After independence, he continued to serve in the military. His superiors viewed him as quarrelsome and Paredes found himself sent to the distant western provinces, embarking from San Blas, but a storm obliged him to return to port and continue the journey on land. In 1831, he was granted the rank of general.[4]

Entry into politics

He found himself becoming involved in politics in 1835 during the collapse of the First Republic. The government had been overthrown in a coup led by Santa Anna, and Mexico was in the process of being transformed from a federal republic into the Centralist Republic of Mexico under a new constitution known as the Siete Leyes. The centralist movement gained the support of Paredes and he was in charge of the 1st brigade which captured Zacatecas from the federalists commanded by Garcia. He then participated in the Southern Campaign in Morelia.

He was promoted to division general in August, 1841 and named commander general of Jalisco.[5] In the same month, due to President Anastasio Bustamante's inability to deal with the various political and financial crises afflicting the nation, Paredes published a manifesto to his fellow commander generals, calling for the formation of a new government. He gathered as many troops as he could, gathered more on the way and entered the city of Tacubaya where he was joined by Santa Anna. A military junta was formed which wrote the Bases of Tacubaya, a plan which swept away the entire structure of government, except the judiciary, and also called for elections for a new constituent congress meant to write a new constitution. Santa Anna then placed himself at the head of a provisional government.[6]

Despite the key role he had played in establishing the new Bases of Tacubaya, Paredes was not invited to accept any position within it, as he was perceived to lack the talents for political administration. He was simply sent back to his post as commander general of Jalisco. Nonetheless, he remained loyal to Santa Anna. The congress which was elected proved itself to be federalist and on 11 December 1842, the Plan of Huejotzingo, which Paredes supported, called for the government to shut down the congress and replace it with a council of notables to continue the work of redrafting the constitution. The plan gained enough support to work and on 6 January 1843, a body of eighty prominent centralists known as the Junta Nacional instituyente was appointed by the government to write a new constitution.[7] The Junta produced a new constitution known as the Bases Orgánicas on June 12, 1843.

Role in Santa Anna's overthrow of 1844

Paredes had been invited by Santa Anna to join the junta which he did so, but left to accept the post of commandant general of the state of Mexico. In the Barracks of the Celaya Battalion, he began to speak candidly against the government and Paredes found himself arrested in his own home, but subsequently absolved of any wrongdoing. The government sought to send him off to Yucatán where he would be less of a danger, but Paredes refused and the government responded by sending him away to Toluca. Paredes found himself feeling exasperated and unappreciated, especially given his key role in having established the entire political order. He became a senator but resigned in July, 1844 after only a month of service in the senate. There were rising tensions with the United States at this time, over the matter of Texas, and a series of forced loans had resulted in much disaffection. Paredes was considering that he could lead a potential revolution.[8]

Knowing that he was still a potential danger, the government sent him off to be stationed in Sonora, but upon arriving in Guadalajara, he proclaimed against the government along with the Departmental Junta and the local garrison. The north of the country joined him, but Santa Anna maintained enough support to prepare a counterattack.[9]

The nominal president at this time was Valentin Canalizo, though under the influence of Santa Anna. Congress condemned Santa Anna for having assumed military command without their authority. The ministers were censured by congress for allowing Santa Anna to imprison the Departmental Assembly of Querétaro and for replacing its governor. The administration responded by having congress shut down, and explaining that its measures were necessary given the ongoing emergency of a potential American annexation of Texas. This led to a military uprising within the capital against Canalizo. He resigned and on 6 December 1844, congress was restored and Jose Joaquin Herrera was installed as the new president with a new ministry. The country was now divided into three loyalties between Herrera's central government, Santa Anna's military forces, and Mariano Paredes' uprising.[10]

Santa Anna with 14,000 men at Silao and on his way to crush Paredes, now proclaimed himself legitimate president and prepared to march upon Mexico City. After finding a siege of the now heavily defended capital impractical, he moved on to Puebla which despite its small garrison offered a fierce resistance. Meanwhile, Santa Anna had learned that Paredes and Herrera had joined forces and were now headed for his own. With the opposing forces about evenly matched, Santa Anna attempted to open negotiations, but Herrera would accept nothing less than unconditional surrender, and Santa Anna began plans to flee the country, only to be arrested near the town of Jico.[11]

Paredes once again found himself in a situation where he had led a decisive revolution without ending up in the presidential seat. He was once again assigned to a post in the north, but found a new pretext for opposing the government as Herrera attempted to negotiate with the United States over the matter of Texas. The president had conceded the possibility of recognizing Texan independence as long as there was no annexation, but this was perceived by his opponents as an alienation of Mexican territory. At this point Paredes had not officially proclaimed against the government and he was assigned to a post near the capital. He however, disobeyed and claimed that he could not obey a treasonous government. He moved his forces to the town of Celaya, claiming to be simply watching over the security of travelers headed to the Lagos Fair. However, from that same town he issued a proclamation expressing that the government was giving away national territory, not upholding the Bases of Tacubaya, and besmirching the national honor.[12]

Presidency

He officially called for the overthrow of the government on 14 December 1845, at San Luis Potosí City. He praised the former Spanish administration of the nation, painted a sorry picture of the Republic, and assured that this would be the last revolution, that he personally sought no office, and that a National Assembly would be installed in which all classes of society would be represented. His plan was ratified by the departmental assembly of San Luis Potosí, and was met with support or at least indifference throughout the rest of the country. The Herrera government however, was able to muster so little support to defend itself that President Herrera gave up the struggle and resigned on 30 December 1845. Paredes and his forces entered the capital three days later.[13]

On 3 January Mariano Paredes finally ascended to the presidency.[14] Paredes formed a new cabinet and proceeded to pass decrees against highwaymen, and for reducing the number of public offices.[15]

On 26 January 1846, an official government convocation was decreed summoning an extraordinary congress with the power to make constitutional changes. The congress was designed to be corporatist. It was to be made up of 160 deputies, representing not geographical areas, but nine classes: land owners, merchants, miners, manufacturers, literary men, magistrates, public functionaries, clergy, and army, elected by the members of those classes.[16]

Monarchical intrigues

The Plan of San Luis Potosí had contained a clause declaring that the constitutional congress it called for should have no restrictions in its abilities to reconstitute the nation. This was widely perceived as opening the path to abolishing the republic and establishing a monarchy. Paredes had expressed monarchist sentiments since 1832, opining that only a monarchy could prevent anarchy and protect the country against American ambitions.[17]

Hence with Paredes as president and an approaching constitutional convention, monarchists saw an opportunity to establish a Mexican throne. During the interval between Paredes' assumption of power and the meeting of the constituent congress, a propaganda war was waged between supporters of a monarchy and of a republic, the former through the newspaper El Tiempo, edited by leading conservative intellectual Lucas Alamán.[18]

In response to El Tiempo and Paredes' perceived monarchism, many Liberal Party newspapers changed their names to reflect their pro-republican stances. El Monitor Constitucional (The Constitutional Monitor) changed its name to El Monitor Republicano (The Republican Monitor). El Siglo XIX (The Nineteenth Century) changed its name to El Republicano (The Republican). Carlos Maria Bustamante began to publish a newsletter titled Mexico no quiere rey y menos a un extranjero, (Mexico doesn't want a king, let alone a foreign one).[19]

Republican critics also pointed out that monarchy was unsuitable to the country because Mexico had no nobility to support such an institution. "With powerful arguments they maintained that the idea of a monarchy in Mexico was not only contrary to the wishes of the Mexican people, but also one that was not at all feasible, there being no such thing as a nobility in the country."[20] Such arguments about the non-existence of a Mexican nobility were echoed by the Conservative statesman, Antonio de Haro y Tamariz, who sarcastically suggested that the government start granting titles to generals.[21]

The perception that his administration was attempting to set up a monarchy led to strong opposition at a time when war threatened to break out with the United States at any moment. On 24 April, after the American invasion had already begun, Paredes issued a manifesto that he supported the republican form of government until the nation shall resolve upon a change.[22]

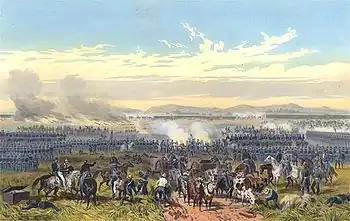

Mexican–American War

In the first few months of the Mexican–American War, the Paredes administration was confronted with a series of catastrophic defeats. U.S. troops under Zachary Taylor had crossed the Rio Grande, and undefeated through a series of battles made it as far south as Saltillo. Meanwhile, American forces were in the process of taking California.

The constituent congress assembled on 6 June. Paredes appeared before it and proclaimed his loyalty to the republican form of government. Six days later, the congress ratified Paredes as president, and chose Nicolás Bravo as vice president with the latter being given command of Mexico's land forces in the ongoing war against the United States. The government was given emergency powers to seek funds for the war effort, stopping at the nationalization of property.[23]

The course of the war inflamed opposition against the government, and facing revolution, Paredes resigned on 28 July, choosing to return to the military to help with the war effort.[24]

On 3 August, the garrisons of Veracruz and San Juan de Ulúa revolted, proclaiming the plan of Guadalajara, and in the upheaval, the ex-president was captured and imprisoned. President Bravo was also deposed and Mariano Salas, the provisional president, on 22 August restored the Federal System which Paredes had played a role in overthrowing eleven years earlier.[25]

Paredes was exiled on 2 October 1846, and headed for France. He returned before the end of the war, but never participated in the conflict, and found himself living in Tulancingo. He was invited to serve in the government, but declined for health reasons. A general amnesty absolved him of all previous charges in April 1849, and he died in September of that year.[26]

See also

References

- “Pedro Lascuráin, El Presidente de México Que Gobernó Por 45 Minutos.” México Desconocido, 3 May 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- Costeloe, Michael P. "Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. Vol. 4, p. 312. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 287.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 287.

- Rivera Cambas, Manueldate=1873. Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruzpages=287.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 287.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 288.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 289.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 293.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 294–295.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 295.

- Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Mexico Desde 1808 Hasta 1867 Tomo II (in Spanish). Perez Dubrull. p. 269.

- Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Mexico Desde 1808 Hasta 1867 Tomo II (in Spanish). Perez Dubrull. p. 271.

- Vigil, Jose Maria (1888). Mexico A Traves de Los Siglos: Tomo IV. p. 556.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1885). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 295.

- Sanders, Frank Joseph (1967). Proposals for Monarchy in Mexico. University of Arizona. p. 163.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 296.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 298.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 299.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. pp. 299–300.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824–1861. p. 299.

Further reading

- Robertson, Frank D. "The Military and Political Career of Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga, 1797–1849". PhD diss. University of Texas, Austin, 1955.

- (in Spanish) Diccionario Porrúa de historia, biografía y geografía de Mexico, 5th ed. rev. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1986, v. 3, p. 2203.

- (in Spanish) Enciclopedia universal ilustrada europea-americana, 1st ed. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1958, v. 42, p. 14.

- (in Spanish) "Paredes y Arriaga, Mariano", Enciclopedia de México, v. 11. Mexico City, 1996, pp. 6206–07, ISBN 1-56409-016-7.

- (in Spanish) García Puron, Manuel, México y sus gobernantes, v. 2. Mexico City: Joaquín Porrúa, 1984, pp. 35–36.

- (in Spanish) Orozco Linares, Fernando, Gobernantes de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial, 1985, pp. 274–76, ISBN 968-38-0260-5.

- (in Spanish) Musaccio, Humberto. Diccionario enciclopédico de México. Mexico: Andrés León, 1989, v. 3, p. 1466.

- (in Spanish) Rivera, Manuel. Los gobernantes de México. Mexico: Imprenta de J.M. Aguilar Ortiz, 1873, v. 2, pp. 286–298.