Marketing mix modeling

Marketing mix modeling (MMM) is statistical analysis such as multivariate regressions on sales and marketing time series data to estimate the impact of various marketing tactics (marketing mix) on sales and then forecast the impact of future sets of tactics. It is often used to optimize advertising mix and promotional tactics with respect to sales revenue or profit.

The techniques were developed by econometricians and were first applied to consumer packaged goods, since manufacturers of those goods had access to accurate data on sales and marketing support. Improved availability of data, massively greater computing power, and the pressure to measure and optimize marketing spend has driven the explosion in popularity as a marketing tool. In recent times MMM has found acceptance as a trustworthy marketing tool among the major consumer marketing companies.

History

The term marketing mix was developed by Neil Borden who first started using the phrase in 1949. “An executive is a mixer of ingredients, who sometimes follows a recipe as he goes along, sometimes adapts a recipe to the ingredients immediately available, and sometimes experiments with or invents ingredients no one else has tried." [1]

According to Borden, "When building a marketing program to fit the needs of his firm, the marketing manager has to weigh the behavioral forces and then juggle marketing elements in his mix with a keen eye on the resources with which he has to work." [2]

E. Jerome McCarthy,[3] was the first person to suggest the four P's of marketing – price, promotion, product and place (distribution) – which constitute the most common variables used in constructing a marketing mix. According to McCarthy the marketers essentially have these four variables which they can use while crafting a marketing strategy and writing a marketing plan. In the long term, all four of the mix variables can be changed, but in the short term it is difficult to modify the product or the distribution channel.

Another set of marketing mix variables were developed by Albert Frey[4] who classified the marketing variables into two categories: the offering, and process variables. The "offering" consists of the product, service, packaging, brand, and price. The "process" or "method" variables included advertising, promotion, sales promotion, personal selling, publicity, distribution channels, marketing research, strategy formation, and new product development.

Recently, Bernard Booms and Mary Bitner built a model consisting of seven P's.[5] They added "People" to the list of existing variables, in order to recognize the importance of the human element in all aspects of marketing. They added "process" to reflect the fact that services, unlike physical products, are experienced as a process at the time that they are purchased. Desktop modeling tools such as Micro TSP have made this kind of statistical analysis part of the mainstream now. Most advertising agencies and strategy consulting firms offer MMM services to their clients.

Marketing mix model

Marketing mix modeling is an analytical approach that uses historic information, such as syndicated point-of-sale data and companies’ internal data, to quantify the sales impact of various marketing activities. Mathematically, this is done by establishing a simultaneous relation of various marketing activities with the sales, in the form of a linear or a non-linear equation, through the statistical technique of regression. MMM defines the effectiveness of each of the marketing elements in terms of its contribution to sales-volume, effectiveness (volume generated by each unit of effort), efficiency (sales volume generated divided by cost) and ROI. These learnings are then adopted to adjust marketing tactics and strategies, optimize the marketing plan and also to forecast sales while simulating various scenarios.

This is accomplished by setting up a model with the sales volume/value as the dependent variable and independent variables created out of the various marketing efforts. The creation of variables for Marketing Mix Modeling is a complicated affair and is as much an art as it is a science. The balance between automated modeling tools crunching large data sets versus the artisan econometrician is an ongoing debate in MMM, with different agencies and consultants taking a position at certain points in this spectrum. Once the variables are created, multiple iterations are carried out to create a model which explains the volume/value trends well. Further validations are carried out, either by using a validation data, or by the consistency of the business results.

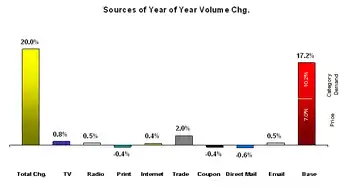

The output can be used to analyze the impact of the marketing elements on various dimensions. The contribution of each element as a percentage of the total plotted year on year is a good indicator of how the effectiveness of various elements changes over the years. The yearly change in contribution is also measured by a due-to analysis which shows what percentage of the change in total sales is attributable to each of the elements. For activities like television advertising and trade promotions, more sophisticated analysis like effectiveness can be carried out. This analysis tells the marketing manager the incremental gain in sales that can be obtained by increasing the respective marketing element by one unit. If detailed spend information per activity is available then it is possible to calculate the Return on Investment of the marketing activity. Not only is this useful for reporting the historical effectiveness of the activity, it also helps in optimizing the marketing budget by identifying the most and least efficient marketing activities.

Once the final model is ready, the results from it can be used to simulate marketing scenarios for a ‘What-if’ analysis. The marketing managers can reallocate this marketing budget in different proportions and see the direct impact on sales/value. They can optimize the budget by allocating spends to those activities which give the highest return on investment.

Some MMM approaches like to include multiple products or brands fighting against each other in an industry or category model - where cross-price relationships and advertising share of voice is considered as important for wargaming.

Components

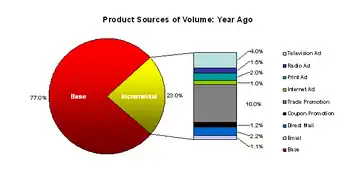

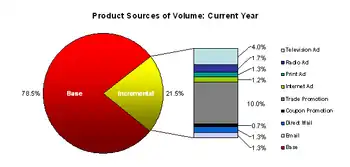

Marketing-mix models decompose total sales into two components:

Base sales: This is the natural demand for the product driven by economic factors like pricing, long-term trends, seasonality, and also qualitative factors like brand awareness and brand loyalty.

Incremental sales: Incremental sales are the component of sales driven by marketing and promotional activities. This component can be further decomposed into sales due to each marketing component like television advertising or radio advertising, print advertising (magazines, newspapers etc.), coupons, direct mail, Internet, feature or display promotions and temporary price reductions. Some of these activities have short-term returns (coupons, promotions), while others have longer term returns (TV, radio, magazine/print).

Marketing-Mix analyses are typically carried out using linear regression modeling. Nonlinear and lagged effects are included using techniques like advertising adstock transformations. Typical output of such analyses include a decomposition of total annual sales into contributions from each marketing component, a.k.a. Contribution pie-chart.

Another standard output is a decomposition of year-over year sales growth/decline, a.k.a. ‘due-to charts’.

Base and incremental volume

The very break-up of sales volume into base (volume that would be generated in absence of any marketing activity) and incremental (volume generated by marketing activities in the short run) across time gain gives insights. The base grows or declines across longer periods of time while the activities generating the incremental volume in the short run also impact the base volume in the long run. The variation in the base volume is a good indicator of the strength of the brand and the loyalty it commands from its users.

Media and advertising

Market mix modeling can determine the sales impact generated by individual media such as television, magazine, and online display ads. In some cases it can be used to determine the impact of individual advertising campaigns or even ad executions upon sales. For example, for TV advertising activity, it is possible to examine how each ad execution has performed in the market in terms of its impact on sales volume. MMM can also provide information on TV correlations at different media weight levels, as measured by gross rating points (GRP) in relation to sales volume response within a time frame, be it a week or a month. Information can also be gained on the minimum level of GRPs (threshold limit) in a week that need to be aired in order to make an impact, and conversely, the level of GRPs at which the impact on volume maximizes (saturation limit) and that the further activity does not have any payback. While not all MMM's will be able to produce definitive answers to all questions, some additional areas in which insights can sometimes be gained include: 1) the effectiveness of 15-second vis-à-vis 30-second executions; 2) comparisons in ad performance when run during prime-time vis-à-vis off-prime-time dayparts; 3) comparisons into the direct and the halo effect of TV activity across various products or sub-brands. The role of new product based TV activity and the equity based TV activity in growing the brand can also be compared. GRP's are converted into reach (i.e. GRPs are divided by the average frequency to get the percentage of people actually watching the advertisement). This is a better measure for modeling TV.

Trade promotions

Trade promotion is a key activity in every marketing plan. It is aimed at increasing sales in the short term by employing promotion schemes which effectively increases the customer awareness of the business and its products. The response of consumers to trade promotions is not straight forward and is the subject of much debate. Non-linear models exist to simulate the response. Using MMM we can understand the impact of trade promotion at generating incremental volumes. It is possible to obtain an estimate of the volume generated per promotion event in each of the different retail outlets by region. This way we can identify the most and least effective trade channels. If detailed spend information is available we can compare the Return on Investment of various trade activities like Every Day Low Price, Off-Shelf Display. We can use this information to optimize the trade plan by choosing the most effective trade channels and targeting the most effective promotion activity.

Pricing

Price increases of the brand impact the sales volume negatively. This effect can be captured through modeling the price in MMM. The model provides the price elasticity of the brand which tells us the percentage change in the sales for each percentage change in price. Using this, the marketing manager can evaluate the impact of a price change decision.

Distribution

For the element of distribution, we can know how the volume will move by changing distribution efforts or, in other words, by each percentage shift in the width or the depth of distribution. This can be identified specifically for each channel and even for each kind of outlet for off-take sales. In view of these insights, the distribution efforts can be prioritized for each channel or store-type to get the maximum out of the same. A recent study of a laundry brand showed that the incremental volume through 1% more presence in a neighborhood Kirana store is 180% greater than that through 1% more presence in a supermarket.[6] Based upon the cost of such efforts, managers identified the right channel to invest more for distribution.

Launches

When a new product is launched, the associated publicity and promotions typically results in higher volume generation than expected. This extra volume cannot be completely captured in the model using the existing variables. Often special variables to capture this incremental effect of launches are used. The combined contribution of these variables and that of the marketing effort associated with the launch will give the total launch contribution. Different launches can be compared by calculating their effectiveness and ROI.

Competition

The impact of competition on the brand sales is captured by creating the competition variables accordingly. The variables are created from the marketing activities of the competition like television advertising, trade promotions, product launches etc. The results from the model can be used to identify the biggest threat to own brand sales from competition. The cross-price elasticity and the cross-promotional elasticity can be used to devise appropriate response to competition tactics. A successful competitive campaign can be analyzed to learn valuable lesson for the own brand. television & Broadcasting: the application of MMM can also be applied in the broadcast media. Broadcasters may want to know what determine whether a particular will be sponsored. This could depend on the presenter attributes, the content, and the time the program is aired. these will therefore form the independent variables in our quest to design a program salability function. Program salabibility is a function of the presenter attributes, the program content and the time the program is aired.

Studies in MMM

Typical MMM studies provide the following insights

- Contribution by marketing activity

- ROI by marketing activity

- Effectiveness of marketing activity

- Optimal distribution of spends

- Learnings on how to execute each activity better e.g. optimal GRPs per week, optimal distribution between 15s and 30s, which promos to run, what SKUS to put on promotion etc.

Adoption of MMM by the industry

Over the past 20 years many large companies, particularly consumer packaged goods firms, have adopted MMM. Many Fortune 500 companies such as P&G, AT&T, Kraft, Coca-Cola and Pepsi have made MMM an integral part of their marketing planning. This has also been made possible due to the availability of specialist firms that are now providing MMM services.

Marketing mix models were more popular initially in the CPG industry and quickly spread to Retail and Pharma industries because of the availability of Syndicated Data in these industries (primarily from Nielsen Company and IRI and to a lesser extent from NPD Group and Bottom Line Analytics and Gain Theory). Availability of Time-series data is crucial to robust modeling of marketing-mix effects and with the systematic management of customer data through CRM systems in other industries like Telecommunications, Financial Services, Automotive and Hospitality industries helped its spread to these industries. In addition competitive and industry data availability through third-party sources like Forrester Research's Ultimate Consumer Panel (Financial Services), Polk Insights (Automotive) and Smith Travel Research (Hospitality), further enhanced the application of marketing-mix modeling to these industries. Application of marketing-mix modeling to these industries is still in a nascent stage and a lot of standardization needs to be brought about especially in these areas:

- Interpretation of promotional activities across industries for e.g. promotions in CPG do not have lagged effects as they happen in-store, but automotive and hospitality promotions are usually deployed through the internet or through dealer marketing and can have longer lags in their impact. CPG promotions are usually absolute price discounts, whereas Automotive promotions can be cash-backs or loan incentives, and Financial Services promotions are usually interest rate discounts.

- Hospitality industry marketing has a very heavy seasonal pattern and most marketing-mix models will tend to confound marketing effectiveness with seasonality, thus overestimating or underestimating marketing ROI. Time-series Cross-Sectional models like 'Pooled Regression' need to be utilized, which increase sample size and variation and thus make a robust separation of pure marketing-effects from seasonality.

- Automotive Manufacturers spend a substantial amount of their marketing budgets on dealer advertising, which may not be accurately measurable if not modeled at the right level of aggregation. If modeled at the national level or even the market or DMA level, these effects may be lost in aggregation bias. On the other hand, going all the way down to dealer-level may overestimate marketing effectiveness as it would ignore consumer switching between dealers in the same area. The correct albeit rigorous approach would be to determine what dealers to combine into 'addable' common groups based on overlapping 'trade-areas' determined by consumer zip codes and cross-shopping information. At the very least 'Common Dealer Areas' can be determined by clustering dealers based on geographical distance between dealers and share of county sales. Marketing-mix models built by 'pooling' monthly sales for these dealer clusters will be effectively used to measure the impact of dealer advertising effectively.

The proliferation of marketing-mix modeling was also accelerated due to the focus from Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 that required internal controls for financial reporting on significant expenses and outlays. Marketing for consumer goods can be in excess of a 10th of total revenues and until the advent of marketing-mix models, relied on qualitative or 'soft' approaches to evaluate this spend. Marketing-mix modeling presented a rigorous and consistent approach to evaluate marketing-mix investments as the CPG industry had already demonstrated. A study by American Marketing Association pointed out that top management was more likely to stress the importance of marketing accountability than middle management, suggesting a top-down push towards greater accountability.

Limitations

While marketing mix models provide much useful information, there are two key areas in which these models have limitations that should be taken into account by all of those that use these models for decision making purposes. These limitations, discussed more fully below, include:

1) the focus on short-term sales can significantly under-value the importance of longer-term equity building activities; and

2) when used for media mix optimization, these models have a clear bias in favor of time-specific media (such as TV commercials) versus less time-specific media (such as ads appearing in monthly magazines); biases can also occur when comparing broad-based media versus regionally or demographically targeted media.

In relation to the bias against equity building activities, marketing budgets optimized using marketing-mix models may tend too much towards efficiency because marketing-mix models measure only the short-term effects of marketing. Longer term effects of marketing are reflected in its brand equity. The impact of marketing spend on [brand equity] is usually not captured by marketing-mix models. One reason is that the longer duration that marketing takes to impact brand perception extends beyond the simultaneous or, at best, weeks-ahead impact of marketing on sales that these models measure. The other reason is that temporary fluctuation in sales due to economic and social conditions do not necessarily mean that marketing has been ineffective in building brand equity. On the contrary, it is very possible that in the short term sales and market-share could deteriorate, but brand equity could actually be higher. This higher equity should in the long run help the brand recover sales and market-share.

Because marketing-mix models suggest a marketing tactic has a positive impact on sales doesn't necessarily mean it has a positive impact on long-term brand equity. Different marketing measures impact short-term and long-term brand sales differently and adjusting the marketing portfolio to maximize either the short-term or the long-term alone will be sub-optimal. For example, the short-term positive effect of promotions on consumers’ utility induces consumers to switch to the promoted brand, but the adverse impact of promotions on brand equity carries over from period to period. Therefore, the net effect of promotions on a brand’s market share and profitability can be negative due to their adverse impact on brand. Determining marketing ROI on the basis of marketing-mix models alone can lead to misleading results. This is because marketing-mix attempts to optimize marketing-mix to increase incremental contribution, but marketing-mix also drives brand-equity, which is not part of the incremental part measured by marketing-mix model- it is part of the baseline. True 'Return on Marketing Investment' is a sum of short-term and long-term ROI. The fact that most firms use marketing-mix models only to measure the short-term ROI can be inferred from an article by Booz Allen Hamilton, which suggests that there is a significant shift away from traditional media to 'below-the-line' spending, driven by the fact that promotional spending is easier to measure. But academic studies have shown that promotional activities are in fact detrimental to long-term marketing ROI (Ataman et al., 2006). Short-term marketing-mix models can be combined with brand-equity models using brand-tracking data to measure 'brand ROI', in both the short- and long-term. Finally, the modeling process itself should not be more costly than the resulting gain in profitability; i.e. it should have a positive Return On Modeling Effort (ROME).[7]

The second limitation of marketing mix models comes into play when advertisers attempt to use these models to determine the best media allocation across different media types. The traditional use of MMM's to compare money spent on TV versus money spent on couponing was relatively valid in that both TV commercials and the appearance of coupons (for example, in a FSI run in a newspaper) were both quite time specific. However, as the use of these models has been expanded into comparisons across a wider range of media types, extreme caution should be used.

Even with traditional media such as magazine advertising, the use of MMM's to compare results across media can be problematic; while the modelers overlay models of the 'typical' viewing curves of monthly magazines, these lack in precision, and thus introduce additional variability into the equation. Thus, comparisons of the effectiveness of running a TV commercial versus the effectiveness of running a magazine ad would be biased in favor of TV, with its greater precision of measurement. As new forms of media proliferate, these limitations become even more important to consider if MMM's are to be used in attempts to quantify their effectiveness. For example, Sponsorship Marketing, Sports Affinity Marketing, Viral Marketing, Blog Marketing and Mobile Marketing all vary in terms of the time-specificity of exposure.

Further, most approaches to marketing-mix models try to include all marketing activities in aggregate at the national or regional level, but to the extent that various tactics are targeted to different demographic consumer groups, their impact may be lost. For example, Mountain Dew sponsorship of NASCAR may be targeted to NASCAR fans, which may include multiple age groups, but Mountain Dew advertising on gaming blogs may be targeted to the Gen Y population. Both of these tactics may be highly effective within the corresponding demographic groups but, when included in aggregate in a national or regional marketing-mix model, may come up as ineffective.

Aggregation bias, along with issues relating to variations in the time-specific natures of different media, pose serious problems when these models are used in ways beyond those for which they were originally designed. As media become even more fragmented, it is critical that these issues are taken into account if marketing-mix models are used to judge the relative effectiveness of different media and tactics.

Marketing-mix models use historical performance to evaluate marketing performance and so are not an effective tool to manage marketing investments for new products. This is because the relatively short history of new products make marketing-mix results unstable. Also relationship between marketing and sales may be radically different in the launch and stable periods. For example, the initial performance of Coke Zero was really poor and showed low advertising elasticity. In spite of this Coke increased its media spend, with an improved strategy and radically improved its performance resulting in advertising effectiveness that is probably several times the effectiveness during the launch period. A typical marketing-mix model would have recommended cutting media spend and instead resorting to heavy price discounting.

See also

References

- Culliton (1948).

- Borden (1964), p. 365.

- McCarthy (1960).

- Frey (1961).

- Booms & Bitner (1981).

- Reddy & Gupta (2009).

- Thomas, Jerry W. (2006). "Marketing Mix Modeling". Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- Booms, B.; Bitner, M. (1981). Marketing strategies and organization structures for service firms. OCLC 153303661.

- Borden, N. (1964). The concept of the marketing mix. OCLC 222909833.

- Culliton, J. (1948). (Culliton, J. 1948).

- Frey, A. (1961). (Frey, A. 1961).

- McCarthy, J. (1960). (McCarthy, J. 1960).

- Reddy, R.K.; Gupta, Amit (12 September 2009). "Get the mix right". The Hindu Businessline.