Marlborough Mound

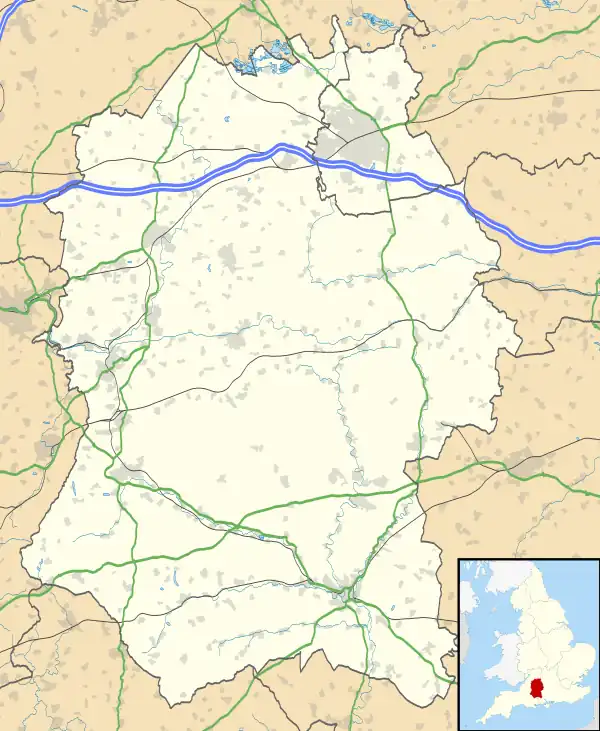

Marlborough Mound is a Neolithic monument in the town of Marlborough in the English county of Wiltshire. Standing 19 metres (60 ft) tall, it is second only to the nearby Silbury Hill in terms of height for such a monument. Modern study situates the construction date around 2400 BC.[1] It was first listed as a Scheduled Monument in 1951.[2]

| Marlborough Mound | |

|---|---|

| Marlborough, Wiltshire, England | |

.png.webp) Marlborough Mound illustrated in William Stukeley's Itinerarium Curiosum | |

Marlborough Mound | |

| Coordinates | 51.416573°N 1.737374°W |

| Type | Artificial mound |

| Height | 19m |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Marlborough College |

| Open to the public | Private Property |

| Condition | Earthworks remain, with 18th-century grotto |

Marlborough Mound is part of a complex of Neolithic monuments in this area, which includes the Avebury Ring, Silbury Hill, and the West Kennet Long Barrow. It is close to the confluence of the River Kennet and lies within the grounds of Marlborough College. Thus it is on private property, unlike other comparable archaeological sites in Wiltshire.[3]

Since construction, the mound has functioned as the motte for a Norman Castle, a garden feature for a stately home, and the site for a water tower within Marlborough College.[4] Today, only the earthworks remain; at its base is a grotto which was part of an 18th-century water feature. In recent years there has been renewed interest in the site pertaining to its restoration and preservation as a culturally and historically significant site in Wiltshire. Additionally, its relation to the nearby Silbury Hill has generated scholarly interest in how the mound constitutes part of a larger archaeological complex in Wiltshire.

Structure and location

The mound is located on the western side of Marlborough within the grounds of Marlborough College, close to the confluence of the nearby River Kennet.[1] It is near Silbury Hill (about 5 miles (8 km) due west of the mound), Hatfield Barrow, Sherrington Mound, Manton Barrow, and Marlborough Common barrow cemetery.

The mound is over 18 metres (59 ft) tall from the present ground surface and its summit has a height of 149.76 metres (491.3 ft) OD. The basal diameter is 83 metres (272 ft), and it measures 31 metres (102 ft) across the top. The structure of the mound has changed over time, often to accommodate the various functions that it has served. By 1654, it had been integrated into the grounds of the stately home built adjacent to it. The occupants, the Seymour family, landscaped the mound and cut or re-cut a spiral path that progressed around the mound from the base to the summit. The walkway is a little over 1.5 metres (5 ft) wide, requiring four circuits of the mound to summit it. Concrete steps are built into the south side of the mound, allowing modern access.[1]

Several academic archaeologists and historians such as Joshua Pollard and Jim Leary have discussed understanding the construction of the mound not in terms of the finished product, but rather as a series of stages. This series is speculated to have taken about a century: a series of smaller mounds progressively enlarged with gravel and clay. Thus, scholars prefer to think about the Neolithic mound in terms of its stages of development and not as a finished product.[5]

Sample cores taken in 2010 by Geotechnical Engineering Ltd provided information about the natural materials used in the mound's structure. These materials included several varieties of clay in several colours such as chalky, pale silty and yellowish brown, as well as flinty gravel. Samples of charcoal were taken which allowed for radiocarbon dating, and these pieces provided the age of the mound as being Neolithic.[1]

Purpose

The original purpose of Marlborough Mound is unclear, but there is wide historical coverage of how the mound has been used through time. A local legend was that the mound was the site of Merlin's burial, given the motto of the town of Marlborough 'ubi nunc sapientis ossa Merlini' (where now are the bones of the wise Merlin).[6] William Stukeley, the antiquarian, believed a Roman fort once occupied the site where the mound is located, based on the finding of Roman coins.[1] Roman artefacts were found in subsequent investigations by A.S Eve in 1892 and H.C Brentnall in 1938.[7][8]

The historian Ronald Hutton speculated in 2016 that the mound was either an oratorical platform used for social purposes by a community, or had ritual meaning to the community.[5]

In 1067, William the Conqueror assumed control of the Marlborough area and assigned Roger, Bishop of Salisbury, to construct the wooden motte-and-bailey castle on the mound. Ethelric, bishop of Selsey was imprisoned and died in the castle in 1070.[9] The neighbouring Savernake Forest was made into a royal hunting ground, and Marlborough Castle became a royal residence. Stone was later used to strengthen it, around 1175. Between 1227 and 1272, Henry III invested in the renovation of the castle, particularly the residential areas, and the chapel of St Nicholas.[10] After his death, Marlborough lost favour as a royal residence. The castle fell into disrepair after it was no longer used from 1370. It was observed to be ruinous after 1541.[8][1] Edward VI then passed it to the Seymour family as he had relations with them through his mother, Jane Seymour.[4]

The Seymours excavated a cavern and built a flint grotto[11] and a spiral path to the summit.[1] In the 18th century, Lady Hertford incorporated the mound into the gardens of the stately home: there was a cascade and a canal, fed from a water tower at the top of the mound,[11][2] and three pools outside the entrance to the grotto reflected sunlight inside from the surface of the water. This usage forms part of a tradition of garden mounds which were prominent in Britain from the end of the 16th century. The shell-decorated grotto is the only remaining relic of these features. It was used as a bicycle shed once the mound ceased to be incorporated into the gardens.[5]

After the last Duke of Somerset on that branch died, the stately home became a coaching house, the Castle Inn, which was operating from 1751. At the height of trade, forty-two coaches passed through the Castle Inn each day as Marlborough was conveniently located on the road from London to Bath.[12]

In the 19th and 20th centuries the mound served as the site for a water tank for Marlborough College, established in 1843, which has since been removed.[4][5]

Investigations

Most recorded investigation and speculation about the mound have occurred from the late 18th century to the present day. The methodologies used by investigators have varied from the use of traditional excavation to modern coring. One of the first investigations was made by William Stukeley in 1776, who wrote in the Itinerarium Curiosum of the recovery of Roman coins at the site.

The 19th and early 20th centuries are characterised by traditional archaeological techniques. The hypothesis that Marlborough Mound was archaeologically connected with Silbury Hill was first posited in 1821 by Richard C. Hoare in his publication The Ancient History of Wiltshire where he placed the two sites within a larger archaeological complex.[13] Hoare suggested that the site was of prehistoric origin. In 1892, a publication of recent excavations at Marlborough College included an antler found in the slopes of the mound.[8] Additional antlers were found in the years afterward by H.C Brentnall, a schoolmaster at the college, and fuelled Hoare's original case for prehistoric origins of the mound in opposition to the idea that it was a burial site for Merlin or constructed solely to accommodate the Norman castle. Brentnall suggested that the impregnation of chalk on the antlers made it unlikely that they could have been buried after the mound's construction.[14] Two Roman coins were recovered from his 'castle ditch'.

As the 20th century progressed, the finding of medieval artefacts as well as a review of previously assembled evidence caused there to be some questioning of the prehistoric origins. In 1955 and 1956, excavations on the western side found refuse from the medieval period, which included Norman pottery. As late as 1997, it was concluded that the mound fitted within the size range of a medieval motte. An analysis of available evidence concluded that without additional findings the mound was 'essentially a medieval construction'.[1]

In the late 20th to early 21st centuries, investigation into the mound continued. The Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England surveyed the mound in 1999.[15] The Marlborough Mound began to be thought of as a possible comparative site to Silbury Hill in 2008. Extracting dateable material from the mound was thought to be best achieved by taking cores from the mound. Geotechnical Engineering Ltd took six cores, two taken from boreholes made at the summit. In a paper by Jim Leary, Matthew Canti, David Field, Peter Fowler and Gill Campbell, the age of the mound was dated to the second half of the third millennium. The earliest date (terminus post quem) for the construction was found to be 2580–2470 cal BC.[1]

The interest in investigating the mound has brought it into a broader discussion of how mounds can be used to learn about the people that lived in this part of Neolithic Britain. These questions have been asked from a variety of interdisciplinary perspectives. Archaeologist Jim Leary has suggested a metaphysical link to, and veneration of, water. His theory is based on proximity to the River Kennet which is also characteristic of Silbury Hill. Rivers in the Neolithic period were a vital means of transport. Geologist Isobel Geddes links the positioning of the mound as an expression of water worship. Nigel Bryant suggested the mound was a monument to the Earth goddess. The period in which the mound and the others in Wiltshire were constructed coincided with the appearance of early English Beakers, which has led to a contention that the construction of the mound is related to an assertion of a native population during a period of social and cultural mobility.[16]

Restoration

The restoration of the mound is in part a response to the state of disrepair of the mound, as well as the renewal of scholarly interest in the mound and the site. In the 1980s, work commenced on restoring the shell grotto, supervised by Diana Reynell (a teacher at the college) and assisted by pupils.[17][4][5]

The restoration effort has been intended to address the risk of collapse and maintain the structural integrity of the mound. Structural conservation has been done as a response to the growing dangers of destabilisation by tree roots.[18] Peter Carey, who managed part of the restoration works, highlighted the overgrowing of trees on the mound as a danger: if one fell, it could risk destroying the entire mound. In 2016, the restoration targeted the removal of the tree canopy, stabilising the earth with grasses, laying fresh soil, and the injection of a gel on top of the mound in order to hold the structure together.[5] Removal of trees and planting of hedges was completed in 2020.[19]

Marlborough Mound Trust

The Marlborough Mound Trust was founded in 2000 and is the main financial backer of the restoration of the mound. The trust strives to conserve it and promote education about it; it declared expenditure of £87,600 for the 2018 financial year.[20] It also supports academic investigations into the mound and funded the coring project that took place in October 2010.

References

- Leary, Jim; Canti, Matthew; Field, David; Fowler, Peter; Marshall, Peter; Campbell, Gill (2013). "The Marlborough Mound, Wiltshire. A Further Neolithic Monumental Mound by the River Kennet". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 79: 137–163. doi:10.1017/ppr.2013.6. ISSN 0079-497X.

- Historic England. "Castle mound, Marlborough (1005634)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "College History". Marlborough College. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Marlborough College (2017). Marlborough Mound: The Mound Trust Marlborough, UK.

- Marlborough Mound Trust (2016). The Marlborough Mound, documentary film, 34:50.

- Stukeley, William (1969). Itinerarium curiosum, or an account of the antiquities, and remarkable curiosities in nature or art, observed in travels through Great Britain. OCLC 640029888.

- Brentnall, H. C. (1938). "Marlborough Castle". Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine. 48 (168): 133–143 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Eve, A (1892). "On recent excavations at Marlborough College". Report of Marlborough College Natural History Society. 41: 65–69.

- Baggs, A.P.; Freeman, Jane; Stevenson, Janet H (1983). Crowley, D.A. (ed.). "Victoria County History: Wiltshire: Vol 12 pp160–184 – Parishes: Preshute". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Ingamells, Ruth Louise (1992). The Household knights of Edward I. (Doctoral thesis). Durham University.

- Historic England. "Grotto at base of south side of Castle Mound (1273151)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- "A SURVEY OF THE HIGHER SCHOOLS OF ENGLAND: MARLBOROUGH COLLEGE". Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. 96: 540–541. 1903.

- Hoare, Richard Colt (1812). The Ancient History of Wiltshire. W. Miller. OCLC 8517399.

- Brentnall, H.C. (1912). "The Mound". Report of Marlborough College Natural History Society. 61: 23–29.

- Field, D, Brown, G (1999). "Field Survey of the Mount at Marlborough: An Earthen Mound at". English Heritage.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Leary, Jim & Peter Marshall (2012). "The Giants of Wessex: the chronology of the three largest mounds in Wiltshire, UK". Antiquity. 86.

- "Diana Reynell" in The Times, 5 September 2017, Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- Whitaker's Shorts, Five Years in Review. Bloomsbury. 2013. ISBN 978-1-4729-0616-8. OCLC 953083711.

- Hinman, Niki (12 September 2020). "Marlborough Mound - latest image of renovation work". This Is Wiltshire. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "The Marlborough Mound Trust, registered charity no. 1081520". Charity Commission for England and Wales.

Further reading

- Barber, Richard, ed. (2022). The Marborough Mound: Prehistoric Mound, Medieval Castle, Georgian Garden. Wodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-186-3.