Marmaduke Dixon (settler)

Marmaduke Dixon (22 March 1828 – 15 November 1895) was an early settler in North Canterbury, New Zealand. He went to sea early in his life before he settled on the north bank of the Waimakariri River. An innovative farmer, he chaired a number of road boards and was a member of the Canterbury Provincial Council.

Marmaduke Dixon | |

|---|---|

| Member of the Canterbury Provincial Council | |

| In office 18 November 1865 – 31 October 1876 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Rickman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 March 1828 Caistor, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 15 November 1895 (aged 67) Christchurch, New Zealand |

| Resting place | East Eyreton Cemetery |

| Spouse | Eliza Dixon |

| Relations | Marmaduke Dixon (son) |

| Children | 4 |

| Residence | Eyreton |

| Occupation | farmer local politician |

Early life

Dixon was born on 22 March 1828 in Caistor, Lincolnshire, England.[1] His forebears owned a large estate in Lincolnshire and were involved in draining The Fens.[2] Dixon received his education at Caistor Grammar School and went to sea aged 14, working for Robert Brooks and Co. On his first voyage, he was wrecked at Pernambuco in Brazil and returned to England on the clipper Swordfish.[3] Dixon went to Australia on several journeys and in 1844 or 1845, a journey took him to New Zealand. As first mate, he went into Port Phillip and they found that 400 ships had been abandoned by their crews for one of the Australian gold rushes, but due to his tact he managed to hold on to his crew. Bishop Selwyn offered Dixon command of his mission yacht but by then, he had decided to take up land in New Zealand on the advice of an Australian squatter, John Murphy, who had established himself at Cust. He left Robert Brooks and Co's employment in 1851 and came to New Zealand on the Samarang, with John Hall as a fellow passenger, which arrived in Lyttelton Harbour on 31 July 1852.[4][5]

Life in New Zealand

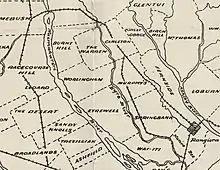

Dixon took a 2,400 hectares (6,000 acres) run on the north bank of the Waimakariri River and called it The Hermitage, but the name changed to Eyrewell.[4] Edward John Eyre was Lieutenant-Governor of New Munster Province from 1848 to 1853 and "well" refers to the hole of 24 metres (80 ft) depth that Dixon dug by hand without reaching groundwater. He later built his homestead nearer to the Eyre River where he had access to groundwater. Unlike other farmers, Dixon freeholded his land and his son, also Marmaduke Dixon, carried on and bought adjacent land from the nearby Burnt Hill and Dagnam runs.[6]

Dixon was an innovator. He converted manuka shrub land to grass land by first planting tussock to protect the finer grass. He imported three-furrow ploughs and was the first to use these in the region. He imported thrashing machines and straw elevators. He is believed to be the first exporter of wheat in bags from Canterbury. In 1887, he built an irrigation intake at the Waimakariri River. At the time of his death, 490 hectares (1,200 acres) of land was under irrigation. His most valuable contribution was his advocacy for irrigation.[4]

Dixon discussed irrigation with the Premier, Richard Seddon. In 1892, the Waimakariri-Ashley Water Supply Board was established.[7] The local member of parliament, David Buddo, initiated the 1894 Waimakariri-Ashley Water-Supply Board Loan Act that gave the board power to borrow up to NZ£3,000.[8] The elected board favoured an intake above the Waimakariri Gorge. Dixon argued for the intake to be built at Browns Rock, some 3.3 kilometres (2.1 mi) downstream from the gorge.[7] Whilst the Browns Rock would irrigate less land, it would be much cheaper to build. Dixon proceeded to build a simple intake near Browns Rock himself in 1892; this was washed away in a flood in 1895. In 1894, the public was frustrated with the board and voted in a new membership, with the new board commencing the Browns Road intake. This was opened by Seddon in 1896, not long after Dixon's death. The company that has taken over the board's assets, Waimakariri Irrigation Ltd, is operating to this day.[7] In 1995, the Browns Rock intake and tunnel was registered by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (now Heritage New Zealand) as a Category II historic item.[9]

Political career

Dixon was the chair of several local road boards and for five years, he chaired all of them: Mandeville and Rangiora, Cust, and East and West Eyreton.[4] After the resignation of Robert Rickman from the Mandeville electorate of the Canterbury Provincial Council,[10] Dixon was declared elected unopposed on 18 November 1865.[11] In the next election on 19 June 1866, where two positions were available, he came second (after Joseph Beswick), just one vote ahead of Andrew Hunter Cunningham, and was thus re-elected.[12] He represented the electorate until the abolition of the provincial government system in late 1876.[13]

Dixon was one of five candidates in the 1881 election in the Ashley electorate for a seat in the House of Representatives. He came a distant third, with William Fisher Pearson winning the election.[14] When Pearson died on 3 July 1888, this caused the 1888 by-election in the Ashley electorate. At the nomination meeting, Dixon won the show of hands.[15] The result of the poll was very close; Dixon came third and with 225 votes, he was just 9 votes behind John Verrall, the successful candidate.[16]

Family and death

In 1859, Dixon returned to England to marry Eliza Agnes Wood, the daughter of Reverend Dr James Suttell Wood of Wensleydale in Yorkshire. They reached New Zealand in December 1860 on the Matoaka. They had two sons and two daughters.

When at the age of 67, Dixon fell ill, he went to Christchurch to Mrs. Rowan's Nursing Home in Durham Street to be near doctors, but he died a few days later,[17] on 15 November 1895. His funeral was held at Christchurch, with the procession then moving to the East Eyreton cemetery by road. Dixon's wife died in May 1905.[1]

References

- Macdonald, George. "Marmaduke Dixon". Macdonald Dictionary. Canterbury Museum. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Cyclopedia Company Limited (1903). "Mr. Marmaduke Dixon". The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : Canterbury Provincial District. Christchurch: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "The late Mr. M. Dixon". The Press. Vol. LII, no. 9265. 16 November 1895. p. 5. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Scholefield, Guy, ed. (1940). A Dictionary of New Zealand Biography : A–L (PDF). Vol. I. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs. pp. 209f.

- Gardner, W. J. "Hall, John". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Acland, Leopold George Dyke (1946). "Eyrewell – (Runs 83 and 93, and later 84)". The Early Canterbury Runs: Containing the First, Second and Third (new) Series. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Limited. pp. 52–54. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "History". Waimakariri Irrigation Ltd. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Waimakariri-Ashley Water-Supply Board Loan Bill 1894 (82–1)". New Zealand Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Browns Rock Intake and Tunnel". New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "The Press". Vol. VIII, no. 927. 27 October 1865. p. 2. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Mandeville election". Lyttelton Times. Vol. XXIV, no. 1541. 20 November 1865. p. 3. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "The Mandeville election". The Press. Vol. X, no. 1144. 9 July 1866. p. 2. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Scholefield, Guy (1950) [First published in 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1949 (3rd ed.). Wellington: Govt. Printer. p. 193.

- Cooper, G. S. (1882). Votes Recorded for Each Candidate. Government Printer. p. 2. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "Ashley election". The Star. No. 6295. 20 July 1888. p. 2. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Ashley Election". The Press. Vol. XLV, no. 7132. 31 July 1888. p. 5. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Obituary". The Press. Vol. LII, no. 9264. 15 November 1895. p. 6. Retrieved 6 December 2020.