Martín Domínguez Esteban

Martín Domínguez Esteban (San Sebastián, December 26, 1897 – New York, September 13, 1970) was a Spanish architect.

Martín Domínguez Esteban | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 26, 1897 San Sebastián, Spain |

| Died | September 13, 1970 (aged 72) New York |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Alma mater | Universidad Politécnica de Madrid |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse | Josefina Ruz |

| Children | 1 |

| Parent(s) | Concepción Esteban Guerendián and Martín Domínguez Barros |

| Practice | Associated architectural firm[s] |

| Buildings | Hipódromo de la Zarzuela, Radiocentro CMQ Building, FOCSA Building |

Biography

Son of Concepción Esteban Guerendián and Martín Domínguez Barros. At seven years Martín Domínguez exhibited a fascination with drawing, he registered in the School of Arts and Offices of San Sebastián which he attended at night while finishing high school. At 17 years of age and after taking his school examinations, he moved to Madrid, passing the entrance exam at the Higher School of Architecture in 1922. He stayed at the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid which housed students from different disciplines. There he made friends with Miguel Prados, José Antonio Rubio Sacristán, José Moreno Villa and Federico García Lorca. Martín Domínguez received his diploma in 1924.[1]

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were not many students of architecture, some of Martín Domínguez's classmates and personalities deserve to stand out for they would be important in his development and career later, such as José María Arrillaga, Fernando Salvador Carreras, Fernando de la Cuadra, Eduardo Figueroa, Eduardo Laforet Altolaguirre, Emiliano Castro Bonel, José Luis Durán de Cottes and Alfonso Jimeno, Felix Candela, Fernando Chueca Goitia, Manuel Múñoz Monasterio or Manuel Rodríguez Suárez. Martín Domínguez and Carlos Arniches began to work together.[2] At this time Martín Domínguez developed his ideology, maintaining a certain rivalry between technocrats and humanists.[3]

In 1924 he was involved in the intellectual and artistic panorama of Madrid and started working with Secundino Zuazo, collaborating with his partner and friend the architect Carlos Arniches. During this period, Martín Domínguez developed new housing, residences, and hotel projects throughout Spain.

In 1925 Martín Domínguez received the commission to reform the ground floor of Madrid's Palace Hotel.[4]

In 1928 he participated, along with Carlos Arniches in the architectural design competition organized by the National Tourism Board for the construction of various roadside lodges, they eventually built 12 of them; this association continued until his exile from Spain in 1936.

Martín Domínguez worked with Carlos Arniches between 1924 and 1936, collaborating in turn with Secundino Zuazo, highlighting works such as the modern and disappeared Café "Záhara" in the Gran Vía, 1930. He also worked on the Project for a hotel in Córdoba, 1928, and the complex of buildings for Primary and Secondary Education at the School Institute, as well as its auditorium and library, 1926 / 1930–1935.

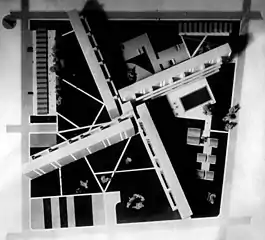

The old Hipódromo de la Castellana (1877–1888), on the site of Nuevos Ministerios, wa265px|s demolished as required by the development of Madrid to the North according to the Plan de Zuazo-Jannsen (opening of the prolongation of the Castellana). The Access and Special Technical Office of Madrid announced a tender to build another one in the term of the Zarzuela (Quinta de el Pardo). The project of Carlos Arniches, Martín Domínguez and the engineer Eduardo Torroja was built between 1934 and 1936. The roof reached 12.8 meters of the span with only 5 centimeters of thickness at its ends, it rests on pillars 5 meters apart.[5]

Le Corbusier

In 1928, Le Corbusier visited the Residencia de Estudiantes, Martin Domínguez spoke with him about the values of Spanish vernacular architecture and motivated Le Corbusier to visit the south of Spain in the summer. The following year, both architects dined with Pierre Jeanneret, cousin and close collaborator of Le Corbusier, and the painter Fernand Léger.

Theory

With regard to style Martín Domínguez, he was attracted by the architectural and urban ideas of Le Corbusier. He never approved a project that was not backed by serious thought, constituting in part one of the principles of rationalism, not to deceive, things should be what they seemed, what they are. For Martín Domínguez, the elements to be used will not be as important as the way to use and combine them. He shared many of the theories defended by Adolf Loos and Tony Garnier, presenting in his works that logical rationalism of Loos along with Garnier's deep concern for society and the environment. This was highlighted by technical, progressive and scientific concerns, where culture and tradition had a relevant and special role to play in modernity far from personal impositions or academic norms.[6]

Fascinated by dynamic and aesthetic impulses, Martín Domínguez made his first trip to the United States in 1932–33.[7]

Exile

He left Madrid at the end of 1936 since he had to go into exile when the Spanish Civil War broke out. He left for France, going first to Valencia where he had to take a boat to Barcelona, and cross the border through the Catalan Pyrenees mountains. On this road, he met Juan Negrín, whom he had met at the Residencia de Estudiantes. He embarked in Antwerp in December 1936, arriving in Havana at the beginning of January 1937. At this time he married the habanera Josefina Ruz and they had a son, Martín, who is also an architect.

Collaboration

He began to work in works in the Cuban territory, from 1938 until his second exile in 1960. He collaborated with the Diario de la Marina, which facilitated his participation in numerous social housing projects, although in collaboration with other architects since he did not have his Cuban architect's registration.[8]

In Havana, he collaborated with three Cuban architecture teams. He worked with Honorato Colete between 1938 and 1943. Later he worked with Miguel Gastón and Emilio del Junco between 1943 and 1948, although since that year he will collaborate only with Gastón until 1952. And finally, with Ernesto Gómez Sampera and Mercedes Díaz between 1952 and 1960, year that must have a second exile, towards the United States.[9]

- With Colete he designed the Gil Plá house, the La Sortija apartments and the Teatro Favorito in Havana (1938), and three houses for the Gómez Mena family in Varadero (1940).

- With del Junco and Gastón, he designed build four houses on the Bocanegra beach, the Enríquez, Roca and Prío houses in Marbella, the Prat and Grau houses in Havana, two apartment buildings in Miramar and Miramar Heights (1946), the Radiocentro CMQ Building (1947), which was a milestone in Havana architecture because it was the first modernist building sporting a curtain wall facade and to seen by all in one of the most important corners in the city. He also designed the Prado and Record Theaters, the Miralda building, the Air Express Office, and in addition the Jibacoa Beach Plan as well as the home of President Grau San Martín in Varadero (1948).

- With Gastón he designed the Miramar Theater and Shopping Center (1949), the Marianao Regulatory Plan (1950), the Santa María del Mar Beach Plan, the Miramar and Atlantic Theaters, a Municipal Building and the open-air Auditorium in Marianao. They also designed the San Diego Spa and the home for President Carlos Prío Socarrás (1950) near Havana.

- The collaboration with Ernesto Gómez-Sampera and his wife, Mercedes Díaz, was a fifty percent partnership that would remain active until 1960, in which the engineer Bartolomé Bestard would be part of the group and, ultimately, the engineer Ysrael Seynuk. They designed the Ministry of Communications (1951–1954), the Workshops Ambar Motor, in Vía Blanca and the building for the Studios of Channel 4 television station. It was this facility that opened the doors for them to other facilities of radio and television on the island. Their great work was the FOCSA Building (1952–1956), which would become the tallest building in Havana with 39 floors and perhaps launching a new typology in modernist single loaded residential design. They also did a series of collective housing projects and inexpensive houses for union pension funds. They also designed the National Institute of Savings and Housing (INAV) after the triumph of the 1959 revolution.

Second exile

In 1960, after his second exile from Cuba, he was hired as a professor in the Department of Architecture, at Cornell University. During this time he traveled to Canada to learn about the new commercial and urban complexes there. He also traveled to South America to advise different governments and housing agencies. Martín Domínguez was a consultant to the Ford Foundation focusing on school projects for the University of Chile, collaborating with the BDI to form a study with Peter Cohen in Rochester, New York writing the remodeling project for the Third District of the city and the design of primary school no. 28. As of 1965, Martín Domínguez was a member of The American Institute of Architects (AIA), his career was recognized through a monograph exhibition held at Cornell University in 1962 at the Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art. In 1967 he executed projects for a single-family home for the Lennox family in Pittsford (Rochester), New York.

Death

Martín Domínguez died in New York City on September 13, 1970, at age 72. A funeral was held in that same city, although he was buried in San Sebastián, Spain. On October 19 a funeral was celebrated in his honor at Cornell University where he spent the last ten years of his life teaching architecture. Dean Burnham Kelly, Professor Colin Rowe and Felix Candela spoke at his memorial. In 1978, the Department of Architecture of the College of Architecture, Arts and Planning of Cornell University dedicated the annual prize "The Martin Dominguez Distinguished Teaching Award" in his honor. In March 2015, the Department of Architecture of Cornell University organized an exhibition dedicated to his life, work, and teaching career.

See also

References

- Diez-Pastor, 2005, p. 24.

- Diez-Pastor, 2005, pp. 25–27.

- "Martín Domínguez". Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- Diez-Pastor, 2005, p. 28.

- Urrutia, A (1997). Arquitectura española del siglo XX. Madrid: Cátedra. pp. 307–310.

- Diez-Pastor, 2005, pp. 35–39.

- "Martín Domínguez". Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- Rabasco Pozuelo, P (March, 2008). Miradas cruzadas, intercambios entre Latinoamérica y España en la Arquitectura Española del siglo XX (Actas preliminares edición). Pamplona: Mairea. pp. 177–185.

- "Ernesto Gómez Sampera". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved 2018-11-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

Bibliography

- Cornell University Faculty Memorial Statement. Martín Domínguez.

- BALDELLOU, M.A., CAPITEL, A., Arquitectura española del siglo XX, Ed: espasa Calpe, vol. XL, Madrid, 2001.

- DIEZ-PASTOR, C., Carlos Arniches y Martín Domínguez, arquitectos de la Generación del 25, Ed. Mairea, Madrid, 2005.

- DIEZ-PASTOR IRIBAS, Mª Concepción (17 marzo, 2003). «Carlos Arniches y Martín Domínguez, y los demás». https://web.archive.org/web/20170215201704/https://serviciosgate.upm.es/tesis/tesis/3573. Consultado el 15 febrero, 2017.

- GÓMEZ DÍAZ, F., Martín Domínguez Esteban. La labor de un arquitecto español exiliado en Cuba, formato digital.

- RABASCO POZUELO, P., Miradas cruzadas, intercambios entre Latinoamérica y España en la Arquitectura Española del siglo XX, Actas preliminares, Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura, Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, marzo de 2008.

- URRUTIA, A., Arquitectura española del siglo XX, Ed: Cátedra, 1997, Madrid.

External links

- Martín Domínguez Esteban Cornell University AAP Architecture Art Planning

- La sombra del arquitecto Martín Domínguez Esteban