Yellow-throated marten

The yellow-throated marten (Martes flavigula) is a marten species native to Asia. It is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List due to its wide distribution, evidently relatively stable population, occurrence in a number of protected areas, and lack of major threats.[1]

| Yellow-throated marten Temporal range: Pliocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Martes flavigula indochinensis in Kaeng Krachan National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Martes |

| Species: | M. flavigula |

| Binomial name | |

| Martes flavigula Boddaert, 1785 | |

| Subspecies | |

|

M. f. flavigula (Boddaert, 1785) | |

| |

| Yellow-throated marten range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Charronia flavigula (Boddaert) | |

The yellow-throated marten, also known as the kharza and chuthraul, is the largest marten in the Old World, with the tail making up more than half its length. Its fur is brightly colored, consisting of a unique blend of black, white, golden-yellow and brown.[2] It is an omnivore, whose sources of food range from fruit and nectar[3] to small deer.[4][5] The yellow-throated marten is a fearless animal with few natural predators, because of its powerful build,[5] its bright coloration and unpleasant odor. It shows little fear of humans or dogs, and is easily tamed.[6]

Although similar in several respects to the smaller beech marten, it is sharply differentiated from other martens by its unique color and the structure of its baculum. It is probably the most ancient form of marten, having likely originated during the Pliocene, as indicated by its geographical distribution and its atypical coloration.[7]

The first written description of the yellow-throated marten in the Western World is given by Thomas Pennant in his History of Quadrupeds (1781), in which he named it "White-cheeked Weasel". Pieter Boddaert featured it in his Elenchus Animalium with the name Mustela flavigula. For a long period after the Elenchus' publication, the existence of the yellow-throated marten was considered doubtful by many zoologists, until a skin was presented to the Museum of the East India Company in 1824 by Thomas Hardwicke.[8]

Characteristics

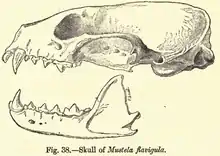

The yellow-throated marten is a large, robust, muscular and flexible animal with an elongated thorax, a small pointed head, a long neck and a very long tail which is about 2/3 as long as its body. The tail is not as bushy as that of other martens, and thus seems longer than it actually is. The limbs are relatively short and strong, with broad feet.[2] The ears are large and broad, but short with rounded tips. The soles of the feet are covered with coarse, flexible hairs, though the digital and foot pads are naked and the paws are weakly furred.[9] The skull is similar to that of the beech marten, but is much larger. The baculum is S-shaped, with four blunt processes occurring on the tip. It is larger than other Old World martens; males measure 500–719 mm (19.7–28.3 in) in body length, while females measure 500–620 mm (20–24 in). Males weigh 2.5–5.7 kg (5.5–12.6 lb), while females weigh 1.6–3.8 kg (3.5–8.4 lb).[10] The anal glands sport two unusual protuberances, which can be used to secrete a strong smelling liquid for defensive purposes.[6]

The yellow-throated marten has relatively short fur which lacks the fluffiness of the pine marten, sable and beech marten. The winter fur differs from that of other martens by its relative shortness, its harshness and its luster. It is also not as dense, fluffy and compact as that of other martens. The hairs on the tail are short and of equal length over the whole tail. The summer fur is shorter, sparser, less compact and lustrous. The color of the pelage is unique among martens, being bright and variegated. The top of the head is blackish brown with shiny brown highlights, while the cheeks are somewhat more reddish, with a mixture of white hair tips. The back of the ears are black, while the inner portions are covered with yellowish gray. The fur is a shiny brownish-yellow color with a golden tone from the occiput along the surface of the back. The color becomes browner on the hind quarters. The flanks and belly are bright yellowish in tone. The chest and lower part of the throat are a brighter, orange-golden color than the back and belly. The chin and lower lips are pure white. The front paws and lower forelimbs are pure black, while the upper parts of the limbs are the same color as the front of the back. The tail is of a shiny pure black color, though the tip has a light, violet wash. The base of the tail is grayish brown.[9] The contrasting marks of the head and throat are likely recognition marks.[6]

Behavior and ecology

Territorial behavior and reproduction

The yellow-throated marten holds extensive, but not permanent, home-ranges. It actively patrols its territory, having been known to cover over 10 to 20 km in a single day and night. It primarily hunts on the ground, but can climb trees proficiently, being capable of making jumps up to 8 to 9 meters in distance between branches. After March snowfalls, the yellow-throated marten restricts its activities up treetops.[11] Estrus occurs twice a year, from mid-February to late March and from late June to early August. During these periods, the males fight each other for access to females. Litters typically consist of two or three kits and rarely four.[5]

Diet

The yellow-throated marten is a diurnal hunter, which usually hunts in pairs, but may also hunt in packs of three or more. It preys on rats, mice, hares, snakes, lizards, eggs and ground nesting birds such as pheasants and francolins. It is reported to kill cats and poultry. It has been known to feed on human corpses, and was once thought to be able to attack an unarmed man in groups of 3 to 4.[3] The yellow-throated marten may prey on small ungulates.[4] In the Himalayas and Burma, it is reported to frequently kill muntjac fawns,[3] while in Ussuriland the base of its diet consists of musk deer, particularly in winter. The young of larger ungulate species are also taken, but within a weight range of 10 to 12 kg. In winter, the yellow-throated marten hunts musk deer by driving them onto ice. Two or three yellow-throated martens can consume a musk deer carcass in 2 to 3 days. Other ungulate species preyed upon by the yellow-throated marten include young wapiti, spotted deer, roe deer and goral.[4] Wild boar piglets are also taken on occasion.[5] It may prey on panda cubs[12] and smaller marten species, such as sables.[4] In areas where it is sympatric with tigers, the yellow-throated marten may trail them and feed on their kills.[5] Like other martens, it supplements its diet with nectar and fruit,[3] and is therefore considered to be an important seed disperser.[13]

Predators

The yellow-throated marten has few predators, but occasionally may fall foul of much larger carnivores; remains of sporadic individuals have turned up in the scat or stomachs of Siberian tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) and Asian black bears (Ursus thibetanus).[14][15] There is a report that a mountain hawk-eagle (Nisaetus nipalensis) kills an adult yellow-throated marten.[16]

Taxonomy

As of 2005, nine subspecies are recognized.[17]

| Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indian kharza (M. f. flavigula) | Bodaert, 1785 | A large subspecies distinguished by the absence of a naked area of skin above the plantar pad of the hind foot, a larger mat of hair between the plantar and carpal pads of the forefoot and by its longer, more luxuriant winter coat[18] | Jammu & Kashmir eastwards through Northern India, the Himalayas to Assam, upper Burma, and southeastern Tibet and southern Kham | chrysogaster (C. E. H. Smith, 1842) hardwickei (Horsfield, 1828) |

| Amur yellow-throated marten (M. f. borealis) | Radde, 1862 | Distinguished from flavigula by its denser and longer winter fur and somewhat larger general dimensions.[19] | Amur and Primorsky Krais, former Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula | koreana (Mori, 1922) |

| Formosan yellow-throated marten (M. f. chrysospila)

|

Swinhoe, 1866 | Taiwan | xanthospila (Swinhoe, 1870) | |

| Hainan yellow-throated marten (M. f. hainana) | Hsu and Wu, 1981 | Hainan island | ||

| Sumatran yellow-throated marten (M. f. henrici) | Schinz, 1845 | Sumatra | ||

| Indochinese yellow-throated marten (M. f. indochinensis)

|

Kloss, 1916 | Distinguished from flavigula by the presence of a naked area of skin above the plantar pad of the hind feet and the area between the plantar and carpal pads on the forefeet. The winter coat is shorter and less luxuriant, with the color being paler, rather yellower on the shoulders and upper back, the loins are less deeply pigmented and the nape is more profusely speckled with yellow. The belly is a dirty white in color and the throat pale yellow.[20] | Northern Tenasserim, Thailand and Vietnam | |

| Malaysian yellow-throated marten (M. f. peninsularis) | Bonhote, 1901 | Similar to indochinensis, but distinguished by its brown, rather than black, head, with the nape being the same color as the shoulders, being usually buff or yellowish brown. The shoulders and upper back are not as yellow as in indochinensis and the abdomen is always darkish brown, while the throat varies from orange-yellow to cream. The fur is short and thin[21] | Southern Tenasserim and the Malay Peninsula | |

| Javan yellow-throated marten (M. f. robinsoni) | Pocock, 1936 | western Java | ||

| Bornean yellow-throated marten (M. f. saba)

|

Chasen and Kloss, 1931 | Borneo |

Distribution and habitat

The yellow-throated marten occurs in Afghanistan and Pakistan, in the Himalayas of India, Nepal and Bhutan, the Korean Peninsula, southern China, Taiwan and eastern Russia. In the south, its range extends to Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, the Malay Peninsula, Laos, Cambodia and Viet Nam.[1]

In northeastern India, it has been reported in Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Himalayan West Bengal and Assam. In the Sunda Shelf it occurs in Borneo, Sumatra, and Java.[22] In Pakistan, it has been reported in different valleys of Gilgit Baltistan, Deosai National Park, Shandur National Park, Phander Valley, Ghizer Valley and Danyor Valley.

In Nepal's Kanchenjunga Conservation Area, it has been recorded up to 4,510 m (14,800 ft) elevation in alpine meadow.[23]

References

- Chutipong, W.; Duckworth, J.W.; Timmins, R.J.; Choudhury, A.; Abramov, A.V.; Roberton, S.; Long, B.; Rahman, H.; Hearn, A.; Dinets, V.; Willcox, D.H.A. (2016). "Martes flavigula". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T41649A45212973. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41649A45212973.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 905–906

- Pocock 1941, pp. 336

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 915–916

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 919

- Pocock 1941, pp. 337

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 910

- Horsfield, T. (1851). A catalogue of the Mammalia in the Museum of the East-India Company. London: J. & H. Cox. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 906–907

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 907–908

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 917–918

- Servheen, C.; Herrero, S.; Peyton, B.; Pelletier, K.; Kana M. and Moll, J. (1999). Bears: status survey and conservation action plan, Volume 44 of IUCN/SSC action plans for the conservation of biological diversity, IUCN, ISBN 2-8317-0462-6

- Zhou, You-Bing; Slade, Eleanor; Newman, Chris; Wang, Xiao-Ming; Zhang, Shu-Yi (2008). "Frugivory and seed dispersal by the yellow-throated marten, Martes flavigula, in a subtropical forest of China" (PDF). Journal of Tropical Ecology. 24 (2): 219–223. doi:10.1017/S0266467408004793. JSTOR 25172915. S2CID 55387571.

- Kerley, Linda L.; Mukhacheva, Anna S.; Matyukhina, Dina S.; Salmanova, Elena; Salkina, Galina P.; Miquelle, Dale G. (2015). "A comparison of food habits and prey preference of Amur tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) at three sites in the Russian Far East". Integrative Zoology. 10 (4): 354–364. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12135. PMID 25939758.

- Hwang, Mei-Hsiu; Garshelis, David L.; Wang, Ying (2002). "Diets of Asiatic black bears in Taiwan, with methodological and geographical comparisons". Ursus. 13: 111–125. JSTOR 3873193. Archived from the original on 2023-04-21. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- Fam, S. D., & Nijman, V. (2011). Spizaetus hawk-eagles as predators of arboreal colobines. Primates, 52(2), 105-110.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Pocock 1941, pp. 331–337

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 914

- Pocock 1941, pp. 338

- Pocock 1941, pp. 339

- Proulx, G.; Aubry, K.; Birks, J.; Buskirk, S.; Fortin, C.; Frost, H.; Krohn, W.; Mayo, L.; Monakhov, V.; Payer, D.; Saeki, M. (2005). "World Distribution and Status of the Genus Martes in 2000" (PDF). In Harrison, D. J.; Fuller, A. K.; Proulx, G. (eds.). Martens and Fishers (Martes) in Human-altered Environments. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 21–76. doi:10.1007/b99487. ISBN 978-0-387-22580-7.

- Appel, A.; Khatiwada, A. P. (2014). "Yellow-throated Martens Martes flavigula in the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area, Nepal". Small Carnivore Conservation. 50: 14–19.

Bibliography

- Allen, G. M. (1938). The mammals of China and Mongolia, Volume 1. New York : American Museum of Natural History.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (2002) [1972]. "Subgenus of Himalayan Martens, or Kharza". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union,]. Vol. II, Part 1b, Carnivores (Mustelidae and Procyonidae). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. pp. 905–920. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.

- Pocock, R. I. (1941). "Charronia flavigula (Boddaert). the Yellow-throated Marten". The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Vol. Mammals 2. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 331–340.

.jpg.webp)