Martha Wall

Martha Alma Wall (March 22, 1910 – August 2, 2000) was an American Christian medical missionary, philosopher, nurse, and author who is best known for her humanitarian work providing health care to lepers in British Nigeria during the 1930s and 1940s with the Sudan Interior Mission (SIM). She was born in Hillsboro, Kansas to a traditional Christian family and was a devout member of both the non-denominational Salina Bible Church and the Baptist Women's Union. She became a registered nurse and studied theology at Tabor College before leaving for a medical mission in British Nigeria in 1938. After returning to America, Wall worked as a Clinical Supervisor of Vocational Nurses for Kern General Hospital during the 1950s and as an instructor and director of nursing services for Bakersfield College during the 1960s. Throughout her adult life, she was a dedicated member of the California State Licensed Vocational Nurses Association. Wall is noted as the founder of the Children's Welfare Center at the Katsina Leper Settlement. She documented her missionary work in Sub-Saharan Africa in the book she authored Splinters from an African Log, which was published in 1960.

Martha Wall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 1920 |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Tabor College |

| Known for | Missionary work with the Sudan Interior Mission (present: Serving In Mission); Creation of the Children's Welfare Center at the Katsina Leper Settlement; Publication of "Splinters from an African Log" |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors |

|

Early life

Martha Wall was born in the rural town of Hillsboro, Kansas. She had a younger sister, Mabel, who moved to California with her husband to be a homemaker before Wall began her missionary work.[1] She was a devout member of both the non-denominational Salina Bible Church and the Baptist Women's Union.[2] Wall's father threatened to disown her when she decided to join a German Mennonite church and expressed her dedication to Christianity, but she eventually convinced him to also believe in the religion. Wall's mother supported her missionary work and passion for medicine.[1]

Education

After becoming a registered nurse, Wall attended the Christian Tabor College, where she took courses primarily focused on biblical studies. She chose to attend Tabor because she could attend classes there while still cheaply living at her parents' home in Hillsboro, which was very close to the school. As required by her curriculum, Wall additionally acted as a Sunday school teacher to a class of high school girls. In addition, Wall wrote for the Tabor Spectator (present: The View) and attended the school's evangelistic Bible conference services. She was initially uninterested in the school's Mission Band club, only beginning to attend meetings after hearing an inspiring sermon about missionary work by a Tabor alumna.[1]p. 14

Personal life

Wall had always felt driven to become a nurse. Before deciding to enter the missionary field, Wall had intended to complete her nursing studies at the more prestigious California University after her graduation from Tabor. Although Wall never married or had children, she claimed to have to loved the toddler orphans who she cared for at the Katsina Leper Settlement and treated them as her own. Wall worked as a Clinical Supervisor of Vocational Nurses for Kern General Hospital during the 1950s and as an instructor and director of nursing services for Bakersfield College during the 1960s.[3] Throughout her adult life, she was a dedicated member of the California State Licensed Vocational Nurses Association, chairing fundraising events and giving tours of her hospital to other nurses.[4]

Mission

Call

When Wall was eighteen, she decided to "accep[t] the challenge of Sheldon's book, In His Steps, to begin to do everything 'as Jesus would do'... willing to give up all pleasures, [her] home--or anything-- to please God."[1]p. 14 As a teenager, Wall dedicated herself to practicing nursing and taking Bible classes at Tabor College, where she was highly involved in extracurricular activities and regularly attended church services. In her book, Splinters from an African Log, Wall writes that during her time at Tabor, she had a poor image of missionaries, as she believed they were outcasts who worked with foreigners because they could not deal with their present realities.[1] She imagined she would attend California University after Tabor to prepare to,

... work only in the finest hospitals with the best staffs and equipment, and perhaps, because the finest hospitals are expensive...have only the wealthiest and most cultured patients.[1]p.95-96

Wall first engaged with the idea of missionary work after listening to a provocative sermon by Tabor missionary alumnus Jake Eitzen in 1937. After the sermon, she imagined God instructing her: "All these years you have been praying every day, 'Lord, make me the kind of nurse that You want me to be.' Well, I am showing you now. This is the kind of nurse I want you to be."[1]p. 21 The next day, Wall read an opinion piece in a leaflet she was given in a science class titled "The Cry of the Leper," which explained the phenomena of Sudan Interior Mission leper colonies in Nigeria. She was initially disturbed and saddened by what she read and attempted to disregard it, believing that missionary work was not a part of the life she imagined for herself and would detract from her journey to becoming a distinguished nurse.

The next week, however, Wall's mother unintentionally turned on the radio to a program about missionary work, which Wall interpreted as a second call by God to encourage her to reconsider her career goals. Although she believed she was not talented enough to be a missionary, she rationalized her decision to apply to the Sudan Interior Mission (SIM), while also applying to work for a hospital in California, because she imagined God instructing her: "What about the lepers in Africa? You have the address of the Sudan Interior Mission (SIM). Why not write [them]? Do you love your own plans more than you love Me?"[1]p. 24 The SIM accepted her application a few weeks later, and Wall agreed to begin training despite private reservations about her father's disapproval and the possibility of contracting leprosy.[1]

Journey

Wall travelled to Monterey, California for the Monterey Bible Conference in late 1937 with the SIM to begin her training and to learn more about what being a missionary would entail. At the conference, Wall was particularly inspired by talks by medical missionaries Dr. Thomas Lambie, Dr. J. Sidlow Baxter, and founder of the Sudan Interior Mission Dr. Rowland Bingham. By the end of her month there, Wall desired a life as a missionary more than a life as a nurse in the United States.

After Salina Bible Church, a church from Wall's hometown of Hillsboro, agreed to financially support her missionary work, she took a train to Brooklyn, New York to meet other SIM missionaries before they left the United States. In November 1938, Wall began her journey from New York to Lagos, Nigeria with the SIM.[1]

Service

During the 1930s and 1940s, Martha Wall acted as a medical missionary for the Sudan Interior Mission in different communities in Nigeria. Her roles included Bible teacher, nurse, doctor, writer, anthropologist, interpreter, photographer, and caretaker for orphans. Wall created the Children's Welfare Center at the Katsina Leper Settlement so that the babies and toddlers of parents with leprosy could live near their parents without risk of contracting the disease, and so they would be taken care of regardless of their parents' health.[5]

Wushishi Compound (Wushishi, Nigeria)

Wall spent her first few months in the Wushishi Compound taking care of orphans and learning Hausa until she gained a strong mastery of the local language. After learning Hausa, Wall taught a basic mathematics and finance class to orphans and adults who requested it. Wall also taught Bible services and reading classes using a Bible translated into Hausa to non-Christian Nigerians with the intention of converting them.[1]

SIM Kano Station (Kano, Nigeria)

Wall acted as the primary doctor for a group of around 40 patients with various medical ailments. Before treating her patients each day, Wall lead morning Bible services as required by SIM protocol. She trained a local teenage boy to help her distribute medicine and interpret for patients who did not speak the form of Hausa she earned in Wushishi. Wall also devoted time to learning about tropical diseases, the British names for medicines, and what medicines can and cannot be mixed. She studied doctors' notes and learned how to make pills and mix ointments.[1]

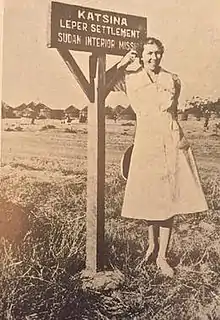

Katsina Leper Settlement (Katsina, Nigeria)

Wall conducted her most impactful missionary work at the Katsina Leper Settlement. She acted as a doctor for hundreds of adults and children with leprosy, treating them with medicine, recording their changing conditions daily, and providing them with emotional and spiritual support. She learned more about the science behind leprosy and novel treatment approaches. In addition, Wall created the aforementioned (see: Service subheading) Children's Welfare Center so that the babies and toddlers of parents with leprosy could live near their parents without risk of contracting the disease and would be taken care of regardless of their parents' health. She prepared meals for, bathed, and medically treated hundreds of these babies and toddlers.[5] At Katsina, Wall also learned more about the impact of Christianity and her mission, SIM, on local Nigerians and developed public health philosophies.[6]

Jega Compound (Jega, Nigeria)

Wall dedicated much of her time at Jega to promoting Christianity among local Muslims, primarily by teaching children Christian hymns. After she had gained their interest, she was permitted to enter their homes and speak with their mothers. Wall believed Islam oppressed women, many of whose husbands she observed treating them as property. She believed Christianity could help Muslim women gain autonomy. Wall's notes on her time at Jega, recorded in Splinters from an African Log, repeatedly express a disgust for the practice of marrying girls without their consent.[1] When a Muslim man refused to let his children be treated by Wall because she was a woman and a Christian, Wall responded sharly, saying that refusing her care made him responsible for the child's death.[7]

Return

Wall officially returned to America from Nigeria in the early 1950s. She worked as a Clinical Supervisor of Vocational Nurses for Kern General Hospital during the late 1950s and as an instructor and director of nursing services for Bakersfield College during the 1960s.[3] Throughout her adult life, she was a dedicated member of the California State Licensed Vocational Nurses Association, chairing fundraising events and giving tours of her hospital to other nurses.[4] After her nursing career, Wall retired to her hometown of Hillsboro, where she died at the age of 90.[8]

Philosophy

SIM values and conversion

Wall agreed with the SIM Christian conversion strategy that it was beneficial to first treat her patients medically and then treat them spiritually by encouraging them toward Christianity. Wall believed that this tactic was particularly important in the devoutly Muslim communities of northern Nigeria, such as Jega. In these regions, doctors and nurses who explicitly promoted Christianity were denied access to patients.[1]

Children's welfare

Wall believed it was her duty as a missionary to act as a caretaker to the children of her patients and to do everything in her power to protect them from infection. She did, however, disagree with SIM’s policy accepting coercion as a means to separate children from parents diagnosed with leprosy, Wall dedicated more time to supporting such children than the SIM missionaries who proceeded her. She explained this philosophy, regarding the opening of the Children's Welfare Center at the Katsina Leper Settlement, in Splinters from an African Log:

By kindness and patience we must win the mothers' confidence. In the meantime we could at least begin to show them that we are kind to babies and children, and that they would be happy with us. If they would bring their babies to us for a few hours a day, we would be able to keep an eye on their general physical condition, checking their weight, treating childhood ailments before they became serious—and we would still be giving these lovely little children a chance to go through life without contracting the disease.[1]p.99

American consumerism

After her missions, Wall sought to make Americans aware of their excessive consumerism and the value they placed on superfluous things. She explained this philosophy in Splinters from an African Log:

I have come to see that buying toys or ice cream or dog food is not sin. The sin lies in permitting Christians to remain victims of a warped sense of values that is impoverishing their own lives and robbing them of a great inheritance [in Heaven]... It is sin to allow earnest young Christians to plan mediocre lives around a materialistic ideal without challenging them to battle. We sin if we do not offer to lead the charge! God has sent us [missionaries] into a stirring conflict, one that should stir response in the blood of every Christian...God holds us responsible for advance![1]p.134-135

Marketing missionary work

Wall was hesitant to simplify or glorify her experiences to attract attention to her cause. In Splinters from an African Log, Wall describes the difficulty of choosing whether to write about an emotional but straightforward experience she had curing a patient or accurately describe the conditions lepers endured and the complex decisions she was forced to make. Wall struggled with how to best to convey the realities she faced while still describing her experiences in a way that would encourage donations and raise interest in missionary work. She explained this philosophy in Splinters from an African Log:

Are we missionaries... partly to blame for this complete oblivion to the worth of a lost soul? Perhaps because we see people so occupied with tangibles, we hesitate to present the real purpose of missions—of our own work—for fear we will offend. People want to be entertained. If we learn how to achieve this art, the contributions toward our work are quite gratifying. So we polish up our best stories.[1]p.133

Legacy

Wall created the first Children's Welfare Center at the Katsina Leper Settlement so that the babies and toddlers of parents with leprosy could live near their parents without risk of contracting the disease and would be taken care of regardless of their parents' health. Although SIM had attempted to create similar Centers before, Wall's was the first successful, sustainable program.[5] She encouraged mothers to allow their children to be treated in this center by hosting weekly banquets where she provided families with food, donated new clothes for their toddlers, and gave baths to their babies.[1]

References

- Wall, Martha (1960). Splinters from an African Log. Chicago: Moody Press.

- "14 Sep 1944, Page 6 - The Emporia Gazette at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

- "The Bakersfield Californian". Article. January 22, 1954. Retrieved December 18, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Bakersfield Californian". Article. February 4, 1954. Retrieved December 18, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Wall, Martha (1940). "The Sudan Witness". Article. pp. 56–57. Retrieved December 18, 2016 – via http://archives.sim.org/.

{{cite news}}: External link in|via= - Byfield, Judith A. (2015). Africa and World War II. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 366. ISBN 978-1-107-63022-2.

- Shankar, Shobana (2014). Who Shall Enter Paradise?: Christian Origins in Muslim Northern Nigeria, c. 1890-1975. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. p. 383. ISBN 978-0821445051.

- U.S. Customs Service (September 10, 1948). "New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957". Passenger Lists. Confirms middle name "Alma". Retrieved December 21, 2016 – via Ancestry.com.