Martyrs of New Guinea

The Martyrs of New Guinea were Christians including clergy, teachers, and medical staff serving in New Guinea who were executed during the Japanese invasion during World War II in 1942 and 1943. A total of 333 church workers including Papuans and visiting missionaries from a range of denominations were killed during the invasion.

Japanese Invasion

After Japan entered war in the Pacific on December 7th, 1941, many civilian populations of Australia's island territories were evacuated. There were fears people of European descent would be in particular danger - along with islanders and Papuans working alongside them - but no order was issued for the evacuation of missionaries.[1] So, many Christians voluntarily chose to continue in their vocation despite the approaching danger. In January 1942 the Anglican Bishop of New Guinea, Philip Strong, advised clergy and staff to faithfully remain working in New Guinea:

“One thing only I can guarantee is that if we do not forsake Christ here in Papua in His Body, the Church, He will not forsake us. He will uphold us; He will strengthen us and He will guide us and keep us though the days that lie ahead. If we all left, it would take years for the Church to recover from our betrayal of our trust. If we remain—and even if the worst came to the worst and we were all to perish in remaining—the Church would not perish, for there would have been no breach of trust in its walls, but its foundations and structure would have received added strength for the future building by our faithfulness unto death.”[2]

The same month Japan captured Rabaul and began its campaign south to the capital Port Moresby. During the campaign hundreds of Christians were killed by the Japanese and collaborating Papuans.

Martyrs

Reported numbers of those killed varies, but the Anglican Board of Mission (Australia) follows the University of Papua New Guinea research that there were:[3]

- Roman Catholic - 197

- United Church - 77

- Salvation Army - 22

- Lutheran - 16

- Anglican - 12

- Methodist - 10

- Evangelical Church of Manus - 5

- Seventh Day Adventist - 4

Anglicans

The Revd. John Barge, priest, sent from England

Sr Margery Brenchley, nursing sister, sent from Queensland

Mr John Duffill, builder, sent from Queensland

Mr. Leslie Gariardi, evangelist and teacher, from Papua

Sr. May Hayman, nursing sister, sent from Victoria

The Revd. Henry Holland, priest, sent from New South Wales

Miss Lilla Lashmar, teacher, sent from Adelaide

The Revd Henry Matthews, priest, sent from Queensland, born in Victoria

The Revd Bernard Moore, priest, sent from England

Miss Mavis Parkinson, teacher, sent from Queensland

The Revd Vivian Redlich, priest, sent from South Africa, born in England

Mr Lucian Tapiedi, evangelist and teacher, from Papua[4]

Methodist

The Revd L.A. Arthur, MLC, BA, DipEd

The Revd W.L.I. Lingwood

The Revd W.D. Oakes

The Revd H.J. Pearson, BA, DipEd

The Revd J.W. Poole, LTh

The Revd H.B. Shelton, BA

The Revd T.N. Simpson, LTh

The Revd J. Trevitt, MA, DipEd

Mr S.C. Beazley

Mr E. W. Pearce[5]

Catholics

On Rabaul, Australians and Europeans who weren't evacuated found refuge at the Vunapope Catholic Mission, until the Japanese overwhelmed the island and took them prisoner in 1942. The local Bishop Leo Scharmach, a Pole, convinced the Japanese that he was German and to spare the internees. A group of indigenous Daughters of Mary Immaculate (FMI Sisters) then refused to give up their faith or abandon the Australians and are credited with keeping hundreds of internees alive for three and half years by growing food and delivering it to them over gruelling distances. Some of the Sisters were tortured by the Japanese and gave evidence during war crimes trials after the war.[6]

Legacy

In 1950 the Right Rev’d Dr Light Shinjiro Maekawa, Anglican Bishop of South Tokyo, sent a bamboo cross to the parishes of all the Martyrs as an act of reconciliation and repentance.[7]

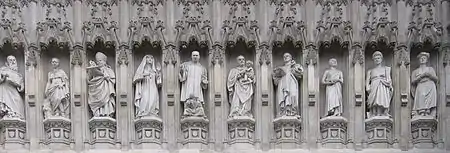

A statue of Tapiedi is installed among the niches with other 20th-century Christian martyrs over the west door of Westminster Abbey in London. His killer, taking the name Hivijapa Lucian, later converted to Christianity. He built a church dedicated to the memory of his victim, which grew to a diocesan center. However, the original building at Higatury was destroyed when Mount Lamington erupted on 21 January 1951 during a diocesan meeting, with considerable loss of life, so the church and center were rebuilt at Popondetta. Another church taking Lucian Tapiedi as its patronal saint is St Lucian's Six Mile[8] in the Six Mile Settlement of Port Moresby, north of Jacksons International Airport.

Veneration

The Martyrs of New Guinea are honored with memorial and feast days on the calendars of many churches including the Anglican Communion on September 2.[9]

See also

Melanesian Brotherhood: seven religious brothers martyred in the Solomon Islands around April 24, 2003.

References

- 'Among the Ruins: The Story of the New Guinea Martyrs' by Padre Arthur Bell (Australian Board of Mission: 1946)

- 'The New Guinea Diaries of Philip Strong, 1936-1945', edited by David Wetherell (1981) p223

- 'The Martyrs of Papua New Guinea' by Theo Aerts (University of Papua New Guinea Press: 1994) Pages 36-7

- The Canberra Times, 25 May 1943, p. 2: 'Renegade Natives hanged for murder of Missionaries' and David Silk, Citizens of Heaven, '2 September, The Martyrs of New Guinea' https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2634266?searchTerm=new%20guinea%20martyrs

- https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/263380563?searchTerm=new%20guinea%20martyrs

- 'It was a real labour of love'; Australian War Memorial

- "New Guinea Martyr: The Rev'd John Barge".

- Michie, Trevor. "Service Times of the Anglican Diocese of Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea". Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 2019-12-17. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.