Mary Ann Williams

Mary Ann Williams (also known as Mrs. Charles J. Williams) (10 August 1821 – 15 April 1874) was an American woman who was the first proponent for Memorial Day, an annual holiday to decorate soldiers’ graves.

Mary Ann Williams | |

|---|---|

from History of Confederated Memorial Associations of the South, 1904 | |

| Born | August 10, 1821 Baldwin, Co., Georgia |

| Died | April 15, 1874 |

| Spouse | Charles J. Williams |

Antebellum years

Mary Ann Howard was born in Baldwin County, Georgia. She was the daughter of Major Jack Howard. She married Charles J. Williams in 1847 when he returned from the Mexican–American War.[1] Mary Ann had presented his regiment with a flag made by the ladies of the city when they left in 1846. According to the 1860 census of Columbus, Georgia, they had four children Charles Howard, Caroline, Mary, and Lila. Charles pursued his career as a lawyer and Mary Ann supported a number of civic projects. Charles entered politics and represented Muscogee County in the Georgia House in 1859-1860 where he rose to be speaker of the Georgia House prior to the Civil War.[2]

Civil War years

Charles left Columbus to command Fort Pulaski on the Georgia coast but gave up that command in order to lead troops in Virginia.[2] Mary Ann joined the Soldiers Aid Society to support the local soldiers in the war effort. He returned to Columbus in February 1862 in very ill health. He died within a few days and was buried in the City Cemetery, now known as Linwood. Mary Ann continued her activities in the Soldiers’ Aid Society and inaugurated the Soldiers’ Home in Columbus.[1] She was said to have visited her husband's grave frequently and was inspired by her young daughter who wanted to decorate the other soldiers’ graves with flowers as well.[3]

Post war years

In early 1866, the Soldiers’ Aid Society was reorganized as the Ladies Memorial Association at the Tyler home on the corner of 4th ave and 14th street. The building is long gone but a monument marks the spot. The officers elected were Mrs. Robert Carter, president; Mrs. Robert. A. Ware, vice president; Mrs. J. M. McAllister, second vice president, Mrs. M. A. Patten, treasurer and Mrs. Williams was elected Secretary of the Association.[4] As secretary, Mrs. Williams was tasked with writing a letter to the ladies of the South to inaugurate an annual holiday to decorate the soldiers’ graves. It is for this letter that she is best remembered. She was also Trustee and Chairman of the Orphan Asylum and Trustee of the Georgia Memorial Association along with Mary Jane Green.[5] She remained active in these organizations until the end of her life.

The letter

The letter Mrs. Williams wrote to her two local newspapers was a request to the ladies of the South to set one day aside each year to decorate the soldiers’ graves. It was long on flowery language and was considered a "thrilling appeal".[6] She did not sign her own name but closed the letter with "Southern Women". It was picked up by newspapers across the South. In The Genesis of the Memorial Day Holiday in America, Bellware and Gardiner provided evidence that her letter was published in cities outside of Columbus, Georgia. The External Links below contain pages from fourteen of the newspapers in Georgia, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, West Virginia, South Carolina and North Carolina where the letter appeared.

Notice outside the South

News of the impending observance spread to cities in the North. Bellware and Gardiner were able to show that Mrs. Williams’ story had gone nationwide. Mrs. Williams’ plan was documented with brief notices in such papers as the New York Times, Hartford Courant, Philadelphia Daily Age and Boston American Traveler. [7]

Holiday observed

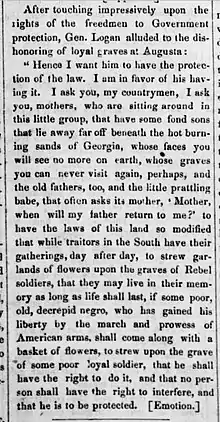

The new holiday was observed throughout the state of Georgia on April 26, 1866, in Atlanta, Augusta, Savannah, Macon, Columbus and numerous other towns. Across the south, it was observed in Montgomery, AL; Memphis, TN, Jackson, MS, Louisville, KY, New Orleans, LA and others. In some locations, most notably Virginia, the tributes were observed on different dates. In Richmond, they decorated on May 31. In Winchester, they decorated on June 6 and in Petersburg, they decorated at Blandford Cemetery on June 9. Due to a typographical error, the holiday was also observed a day early in at least one location. The Memphis Appeal apologized for the error in their April 25, 1866 edition.[8] The ladies of Columbus, MS reportedly observed the holiday on April 25, 1866, and also decorated the graves of Union soldiers, as well.[9] Not all the observances were as noble. In Augusta, Georgia, officials did not allow African-Americans to decorate the graves of Union soldiers which resulted in widespread negative press reports.[10]

The news was so widespread that it would have been difficult to have missed the coverage. One person who took notice was General John A. Logan, the future commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). As he was the person responsible for the observance of the first northern Memorial Day on May 30, 1868, it has always been a question of when Logan learned about the southern tradition he was adopting. Bellware and Gardiner point out that Logan knew about the southern holiday from the beginning, as evidenced by a speech on July 4, 1866, at Salem, IL that argued for the rights of the Freedmen while mentioned the southern observances two years before adopting the holiday in the north.[7]

Death

Mrs. Williams died on April 15, 1874, less than two weeks before the ninth observance of Memorial Day in Columbus. Her funeral was held on April 16 and was attended by the Columbus Guards. Ten days later, at the end of the Memorial Day wreath laying ceremonies, the battalion of the Columbus and City Light Guards stacked arms. Then, each soldier proceeded to Mrs. Williams’ grave and one-by-one laid a rose on her grave as they passed.[11]

Hoaxes and False Claims

Over two dozen places claim to have originated the Memorial Day holiday. The University of Mississippi's Center for Civil War Research under the direction of Dr. John R. Neff maintains a web page listing several of the "originators."[12] The text on that page states that "So widespread was the impulse to honor the war dead that observances occurred spontaneously in several locations..." and "...these numerous early ceremonies tend to blur the origins of this now national tradition." In reality, it appears that the origin of the holiday was blurred by the impulse to take credit where it was not due. In 2022, the National Cemetery Administration, a division of the VA, credited Mrs. Williams with originating "The idea of strewing the Civil War graves of soldiers — Union and Confederate" with flowers.[13]

While many of the places on this list, like Columbus, GA, Columbus, MS, Memphis, TN and Richmond, VA were simply decorating at the request of Mrs. Williams. Several of the stories are clearly fraudulent claims made by people seeking some sort of credit or glory for themselves or their town.

The following people and places have been used to take credit from Mrs. Williams by making fraudulent claims for events that never happened or mischaracterizing events that had no impact on the inauguration of the holiday:

- Kingston, GA

- Lizzie Rutherford of Columbus, GA

- Woodlawn Cemetery, Carbondale, IL

- Sue Landon Vaughan formerly of Jackson, MS

- Henry C. Welles and Gen. John B. Murray of Waterloo, NY

- Martha Kimball of Philadelphia, PA

- Emma Hunter, Sophie Keller and Elizabeth Meyers of Boalsburg, PA

- James Redpath at Hampton Park, Charleston, SC and his friend Charles Cowley

- Nora Fontaine Davidson and Blandford Cemetery, Petersburg, VA

- Norton Parker Chipman, Adjutant General of the GAR

References

- "Death of Mrs. Chas. J. Williams". Columbus Daily Enquirer. April 16, 1874.

- "Death of Gen. Chas. J. Williams". Columbus Daily Enquirer. February 5, 1862.

- Chipley, W. D. (March 15, 1899). "Origin of Memorial Day". The Watchman and Southron.

- The History of the Origin of Memorial Day. Columbus, Georgia: Gilbert Printing Co. 1898. p. 18.

- "Death of Mrs. Chas. J. Williams". The Columbus Daily Enquirer. April 16, 1874.

- Behan, Mrs. William J. (1904). History of Confederated Memorial Associations of the South. New Orleans: Confederated Southern Memorial Association/ The Graham Press. p. 135.

- Bellware, Daniel and Richard Gardiner, PhD. (2014). The Genesis of the Memorial Day Holiday in America. Columbus, Georgia: Columbus State University. pp. 46, 31. ISBN 9780692292259.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "We were in error". Memphis Appeal. April 25, 1866. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- "Editorial and Other Items". New Orleans Times. May 1, 1866.

- "News of the Day". The New York Times. May 6, 1866.

- "Ninth Memorial Day". The Columbus Daily Enquirer. April 28, 1874.

- Neff, Dr. John R. "Memorial Day". Center for Civil War Research. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- "Memorial Day History". cem.va.gov. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

External links

- The Southern Dead, Tri-Weekly Constitutionalist, Augusta GA, March 14, 1866

- The Graves of Confederate Soldiers, Memphis Daily Appeal, Memphis, TN, March 17, 1866

- The Soldiers’ Graves, Daily Intelligencer, Atlanta, GA, March 21, 1866

- The Southern Dead, Savannah Daily Herald, Savannah, GA, March 21, 1866

- The Graves of Confederate Soldiers, Oxford Falcon, Oxford, MS, March 22, 1866

- The Soldiers' Graves, Tri-Weekly Courier, Rome, GA, March 24, 1866

- Woman's Honor to the Gallant Dead, Weekly Georgia Telegraph, Macon, GA, March 26, 1866

- The Southern Dead, Staunton Spectator, Staunton, VA, March 27, 1866

- The Southern Dead, The Anderson Intelligencer, Anderson Court House, SC, March 29, 1866

- The Southern Dead, Selma Morning Times, Selma, AL, March 30, 1866

- Woman's Honor to the Gallant Dead, Southern Recorder, Milledgeville, GA, April 3, 1866

- In Memory of the Confederate Dead, The Daily Phoenix, Columbia, SC, April 4, 1866

- In Memory of the Confederate Dead, Wilmington Journal, Wilmington, NC, April 5, 1866

- The Southern Dead, Shepherdstown Register, Shepherdstown, WV, April 14, 1866