Mary E. Hutchinson

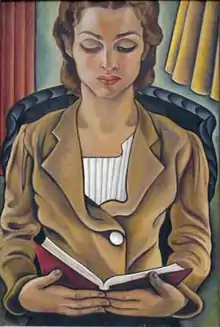

Mary E. Hutchinson (July 11, 1906 in Melrose, Massachusetts – July 10, 1970 in Atlanta, Georgia)[2] was an artist and art instructor from Atlanta who lived and worked in New York City during the years of the Great Depression and World War II.[3] She specialized in figure painting, particularly portraits of female subjects. New York critics described these portraits as "sculptural,"[4] having a "bold yet rhythmic design,"[5] and often possessing a "haunted mood".[6] Critics noted the "introspective" nature of some portraits whose subjects showed "an almost morbidly brooding sensitiveness."[7] From 1934 to 1943 she was a member of the Art Teaching Staff of the WPA New York Federal Art Project.[3][8]: 154 Following her return to Atlanta in 1945 Hutchinson was an art teacher in Catholic high schools.[3]

Mary E. Hutchinson | |

|---|---|

Mary E. Hutchinson, Self Portrait, circa 1927 | |

| Born | July 11, 1906 Melrose, Massachusetts |

| Died | July 10, 1970[1] Atlanta, Georgia |

Art training

Hutchinson took an art course while a student at Agnes Scott College[9][10][note 1] and subsequently studied at the National Academy of Design where she won three awards, one each in sculpture, drawing, and etching.[9][11][12][note 2] She began taking classes at the Academy as a scholarship student in 1926 and took her last class in 1931.[17] During her five years of study her main interest was sculpture.[18]

Artistic career, early 1930s

In the year following her last class at the Academy Hutchinson showed in group exhibitions at the G.R.D. Studio,[5][19][note 3] in a restaurant-cum-gallery called the Jumble Shop,[23][note 4] and in a sidewalk art sale in Washington Square Park.[25][note 5] In 1933 she was given both group and duo exhibitions at the Painters and Sculptors' Gallery[6][30][note 6] and participated in group shows at the Brevoort, Roosevelt, and Weston hotels.[33][34][35][note 7] The statement that Hutchinson's portraits possessed a "haunted mood" came from Howard Devree's review of the duo exhibition which also said the portraits were "instinct with sympathy."[6][note 8]

Early in 1934 Hutchinson was given her first solo exhibition and two of her paintings were purchased by the new High Museum of Art in Atlanta.[18][38][note 9] Appearing at Midtown Galleries, the solo exhibition drew praise and generated the most detailed consideration of her work to date.[note 10] Devree said her talent was maturing, revealing skillful design and a subtler use of color[7] He also remarked on the introspection, sensitivity, and brooding quality brought out in her subjects and on their sculptural quality.[42] A review in the New York Sun paid Hutchinson a compliment by reproducing one of the portraits, "Helen," but the text was not so complimentary, noting a use of hard outlines to reinforce contours which resulted in a loss of "an enveloping atmosphere" and suggesting that her portraits made too "bald a statement."[18] Later in 1934 and over the following two years Hutchinson participated in group shows at Midtown Galleries and the A.C.A. Gallery.[note 11] She also began showing in group exhibitions sponsored by the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors whose juries presented her with awards in 1934, 1935, and 1938.[note 12] In 1935 Hutchinson participated in a duo-exhibition at the Ten Dollar Gallery showing, as Devree said, "brooding portraits" that "have been seen in a number of local galleries" along with abstract pictures made by her mother, Minnie Belle Hutchinson.[49][note 13] At that time she also became a member of the New York Society of Women Artists, showing in the tenth annual exhibition of that group and eliciting a favorable comment on one of her paintings.[54][note 14]

Artistic career, late 1930s

In the second half of the 1930s Hutchinson continued to participate in group exhibitions held by the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors as well as ones held by the Midtown and other galleries. Beginning in 1936 paintings of hers were selected to appear in exhibitions sponsored by the New York Municipal Art Committee,[56][57][note 15] the Art Mart,[61][note 16] and the Art Institute of Chicago.[63] She also began to exhibit in annual shows held by the Society of Independent Artists.[note 17] In May 1936 she was one of forty New York artists selected to participate in an exhibition of works from the city and each U.S. state. The group was a prestigious one, including Alexander Archipenko, Charles E. Burchfield, Arthur Dove, William Glackens, Harry Gottlieb, Edward Hopper, Walt Kuhn, Georgia O'Keeffe, John Sloan, and Bradley Walker Tomlin.[67][note 18]

Early in 1937 Hutchinson was given a solo exhibition in the mezzanine art gallery of the Barbizon-Plaza hotel. In reviewing the show Howard Devree saw a decade of progress in her paintings as she gradually moved toward "simplification, sureness, subtler color values, inspired by a lively decorative sense."[68][note 19]

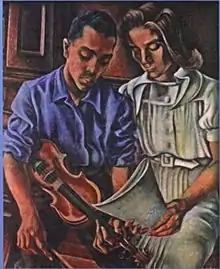

Hutchinson showed her painting, "The Duet," in her solo exhibition in the Midtown Gallery in 1937 and showed it again the following year when it won the award mentioned above. On both occasions critics voiced mixed feelings about it. In November 1937 a critic for the New York Sun noted a regrettable "tendency to blackness and hard contours" in it and other portraits of the time[75] and in January 1938 a critic, also from the New York Sun, said it was "boldly conceived" and able to dominate the room in which it was hung, but the couple shown were "so 'posed' that they seem almost to have been frozen into their positions."[76] Later that year the critic, Margaret Breuning, called it a "startling" canvas that "hits you between the eyes at first viewing, but has nothing to say after this first violence of onslaught."[77] Hutchinson showed the painting twice more over the next few years and it attracted enough attention to be reproduced in art journals and newspapers.[78]: 408 In a 1940 interview Hutchinson said people failed to see the message she intended it to give. In showing a young couple studying a sheet of music—the man being an African American and the woman a white person—she hoped to convey that "through the arts racial barriers are eliminated."[10][note 20] Hutchinson was working in a federally-funded neighborhood center in Harlem at the time she painted "The Duet." While employed at the center she made other portraits of African Americans as well. These included "The Composer" and "The Composer at His Keyboard" with Luke Theodore Upshure as the model; "Shine Boy" and "George Griffiths" and "George Griffiths Sleeping" with George Griffiths as the model; and one, "Night," where the model's name is not known.[75][79][80][note 21]

In 1938 Hutchinson was elected to the board of directors of An American Group Inc.[85] and showed in a thematic exhibition that group put on at Maison Française called "Roofs for 40 million."[86][note 22][note 23] The following year she was one of 250 members of the American Artists Congress to show work in an exhibition called "Art in a Skyscraper" put on at 444 Madison Avenue.[92]

Reporters interviewed Hutchinson in 1937 and 1940. Both times she made light of her career, explaining in the first of them that her great success when young was in playing singles tennis rather than in painting, mentioning her failing grade in a college art course, and lamenting that a prize for work in sculpture while at the National Academy led merely to work "painting flowers on waste baskets."[9] In the second she explained that she could not abide the rigid technical discipline imposed by her college and academy instructors and wanted the freedom to paint portraits from life.[10]

Artistic career, 1940s and 1950s

During the first half of the 1940s Hutchinson continued to exhibit with three membership organizations—the National Association of Women Artists, the New York Society of Women Artists, and the Society of Independent Artists—and she joined and exhibited with a fourth, the League of American Artists.[78]: 384 [note 24][note 25] In 1945 the Studio Gallery produced a duo-artist exhibition of drawings by Hutchinson and watercolors by her mother[98] and during the rest of the 1940s she continued to show with membership organizations but did so at a distance since, following the death of her father that year, she had moved from New York back to Atlanta to live with her mother.[78]: 384 In 1953 she participated in a group show held by the National Association of Women Artists devoted to works by members from the state of Georgia.[99] Otherwise, in the 1950s and during the rest of her life she taught art in Catholic high schools in Atlanta and rarely showed her work.[note 26]

Exhibitions

A list of exhibitions is given in a web site called "Artworks of Mary E. Hutchinson" by Jae Turner.[25]

Art teacher

Hutchinson was employed as an artist-teacher and supervisor of teachers in a community art center located in Harlem between 1935 and 1943.[3][8]: 154 [78]: 382, 384 [100][note 27]

On relocating to Atlanta in 1945 and for the rest of the 1940s Hutchinson served on the faculty of the High Museum School of Art and its successor the Atlanta Art Institute.[17][102] Thereafter she taught in Catholic high schools in Atlanta.[3]

Personal information

Hutchinson's father was Merrill Marquand Hutchinson. He was born in Mexico City in 1874 and died in 1945, in Atlanta.[103][104] Her mother was Minnie Belle Bradford Hutchinson. She was born in Enfield, New Hampshire, in 1875 and died in 1959.[105] At the time of her father's birth, his father, Merrill N. Hutchinson, and his mother, Mary Louise Trask Hutchinson, were leading a Presbyterian mission in Mexico City.[106][107][note 28] Hutchinson's parents were married in Boston, Massachusetts, in September 1905 and she was born in Melrose, Massachusetts, on July 11, 1906.[105][109] Due to infant fatalities she was raised as an only child.[110][111] At the time of her birth Merrill was a church organist in New York.[112][note 29] In 1908 the family moved to Atlanta where Merrill was both a church organist and director of music in a private school for girls and Minnie Belle, who before her marriage had taught elocution in Boston, was an instructor of voice culture and dramatic expression first in the same school where Merrill worked and later in the school where Hutchinson received her high school education.[note 30] By 1930 Merrill had become a practitioner of Christian Science while she remained a teacher of expression.[126] Ten years later they were both self-employed practitioners of that faith, he at the age of 66 and she at 65.[127]

Hutchinson's high school, which she attended between 1920 and 1922, was Washington Seminary[10][125][128][note 31] While at the seminary Hutchinson developed into a champion tennis player.[10][129][130][note 32] In 1924 and 1925 Hutchinson studied at the Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia.[10][131][132] [note 33] She lived in New York while studying at the National Academy and remained there during the 1930s and the years of World War II but returned to Atlanta in 1945 after the death of her father. At that time she and her mother rented an apartment and lived together there for the rest of her mother's life.[78] Following her mother's death she continued to live in the same apartment for the rest of her life.[3] Hutchinson never married and from 1931 onward generally shared her life with a succession of women partners.[78]: 5–6

Other names

Hutchinson's name was usually given as Mary E. Hutchinson. Less frequently it was cited either without the middle initial or in full as Mary Elizabeth Hutchinson.[note 34]

Notes

- Hutchinson said she failed her college art class because she could not tolerate its rigid technical discipline.[9]

- Information is lacking about the sculpture prize that Hutchinson won. The drawing prize was a Suydam bronze medal, shared with Joan Starr, which she received for a figure study while attending the women's night class in 1928.[11] The etching award was an honorable mention shared with Virginia Snedeker and Dorothy Drew.[12] Named after James Augustus Suydam, the Suydam medal was originally a pair of prizes, silver and bronze medals, given to the students who made the best work in a live-model drawing competition.[13] In Hutchinson's time there were multiple awards in the Antique and Life Schools which were given to students in the men's and women's day and night classes for drawings of heads and figures, both from life and from classical reproductions.[14][15] In 1929 a report in the alumnae quarterly of Agnes Scott College said that Hutchinson had won "quite a bit of recognition" while studying at the Academy.[16]

- The G.R.D. Studio was an "excellent little gallery at 58 West Fifty-fifth Street, operated through the courtesy of Mrs. Philip J. Roosevelt, mainly as a forum for young and unknown artists."[20] A non-commercial venture which charged no commissions, it was founded in 1928 as a memorial to the artist Gladys Roosevelt Dick by her sister, Mrs. Philip J. Roosevelt.[21][22]

- The Jumble Shop was a restaurant located near art galleries in Greenwich Village. Early in 1932 it began to display pictures by young American artists which had been selected by a committee of artists, Guy Pène du Bois, H.E. Schnakenberg and Reginald Marsh.[20][23][24]

- The sidewalk art sale was put on by the Artists' Aid Committee, a group of struggling artists whose chair was Vernon C. Porter. The group obtained permission to hold the event and invited artists to participate, charging no fees and permitting artists to sell directly to the public. Begun in May 1932 the exhibitions have continued annually or semi-annually into this century.[26][27][28][29]

- Founded in November 1931, the Painters and Sculptors' Gallery offered low cost pictures and sculptures suitable for the small apartments in which most New Yorkers lived. Called a cooperative venture, it offered aspiring and unknown artists the opportunity to obtain sales at low commissions and with no delay in payment from the gallery. It was organized by a young painter, Margit Varga, whose family had emigrated to New York from Hungary when she was ten.[31][32]

- One of the hotel exhibitions employed an unusual format. Put on by the Artists Aid Committee it permitted prospective customers to rent pictures with the option of buying later if they chose. Styled as an "Art Lending Library," the exhibition appeared in the Empress Gallery and Adam Room of the Weston Hotel. In this show, a review in the New York Sun singled out a painting of Hutchinson's called "Aria Trista" as being "particularly striking" and said her work had been receiving favorable attention from critics.[35]

- Howard Devree (1891–1966) became an assistant art editor at the New York Times in 1926 and succeeded to the post of art editor on the death of Times critic Edward Alden Jewell in 1947. Between 1926 and 1947 he worked for the Sunday edition of the paper writing book reviews and cultural articles as well as art criticism.[36][37]

- The works purchased by the High Museum were "Two of Them" and "Italian Girl."[38] The High Museum evolved from the Atlanta Art Association when, in 1926, Harriet Harwell Wilson High, wife of a prominent Atlanta department store owner, donated her family's Peachtree Street townhouse to the association for use as a museum. Known for its holdings of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American artists, its collections also include contemporary art, photographs, and works by African-Americans.[39]

- The Midtown Galleries was founded by Alan D. Gruskin in 1932 as a cooperative venture in which participating artists both helped pay the costs of exhibitions and contributed their labor to staging them. Gruskin and a partner, Francis C. Healey, publicized the business via weekly fifteen-minute radio broadcasts. Gruskin also used print advertisements, review articles, and catalog essays to promote the gallery and its artists. He was one of the first gallery owners to circulate exhibitions among colleges and art associations in small communities that lacked museums and commercial galleries. In addition to running the gallery he consulted with corporate clients on the use of art in space design and he wrote monographs, including Painting in the U.S.A. (Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Co., 1946), The water colors of Dong Kingman, and how the artist works (New York, Studio Publications, 1958), and The painter and his techniques: William Thon (New York, Viking Press, 1964).[40][41]

- The A.C.A. Galleries, also known as the American Contemporary Arts Gallery, was founded in 1932 to support the careers of little-known American artists by Lithuanian-born journalist and author, Herman Baron, along with the artists Stuart Davis, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Adolf Dehn.[43][44] Hutchinson's paintings at the A.C.A. exhibition included a departure from her usual portraits, called "Sixth Avenue L," which, said a critic for the New York Sun, "is a solid and compactly organized canvas, marked by an expressive use of curves and soberly satisfying color." The critic said the portraits were "more in her usual sculpturesque vein" and praised one showing Margit Varga, "in which there is a hint of a sensitive and elusive personality."[45]

- In 1934 Hutchinson won a first prize for a painting called "Doll."[46] In 1935 she won the Marjorie R. Leidy Memorial Prize of $100 for "Nude."[47] In 1938 she was awarded the Marcia Brady Tucker Prize of $100 for "The Duet."[48]

- Early in 1934 the Upstairs Gallery changed its name to the Ten Dollar Gallery and set a top price of $10 on each of the works it offered for sale.[50] The Upstairs Gallery was founded late in 1933 by Mrs. Marguerite Zimbalist at the same location to sell works by deserving artists at low cost.[51] Marguerite Zimbalist was a poet and friend of the artist Louis Eilshemius.[52] Minnie Belle Hutchinson took up poetry and art after Hutchinson left home for New York. Hutchinson reported that she convinced her mother to take up painting and said her style grew out of a practice of doodling.[3][53]

- In 1926 a group of women artists founded the New York Society of Women Artists as a progressive alternative to the National Association of Women Artists. Membership was originally limited to thirty, later lifted to fifty, and each member was allotted the same amount of space in its exhibitions.[55] Of the works she contributed to the 1935 annual exhibition of the society (held at the Squibb Galleries), a critic for the New York Times commented that "Mary Hutchinson, momentarily abandoning her preoccupation with the papery young ladies, gives us a diverting 'Negro Shack,' gay and piquant in treatment."[54]

- New York's mayor, Fiorello La Guardia established the Municipal Art Committee in the fall of 1934 to provide employment for New York's musicians, performers, artists, and other out-of-work arts workers. Early in 1936 the committee opened a gallery, the Temporary Municipal Galleries, 62 W. 53rd Street. Groups of artists submitted applications to the committee and exhibitions were changed every two months.[58][59] In May 1936 Hutchinson joined with eleven other women in a successful application to appear in a Municipal Art Committee show. The other eleven artists were Theresa Bernstein, Dorothy Eisner, Dorothy Lubell Feigin, Lucie Hourdebaight, Adelaide Lawson, Magda F. Pach, Mildred Peabody, Edna L. Perkins, Ellen Ravenscroft, Jane Rogers, and Mary Tannahill.[60]

- Miriam Sachs and Betty Ackerberg founded the Art Mart in 1935 to show the work of young American artists in gallery space on the mezzanine of the Sachs Quality Furniture Store on 25th Street. They offered paintings, prints, and drawings at prices ranging from $1.00 to $100.00.[62]

- Founded in 1916, the Society of Independent Artists followed the model of the Parisian Société des Artistes Indépendants in giving anyone the right to participate in its annual exhibitions on payment of a modest fee ($5.00 during the time in which Hutchinson participated).[64] Works were hung alphabetically by artist's name in its annual exhibitions and the alpha starting point for each show was determined by random selection.[65][66]

- Hutchinson was chosen to participate in the First National Exhibition of American Art by a committee appointed by the governor of New York State and mayor of New York City. Held on the mezzanine floor of the International Building in Rockefeller Center, the show included forty works from New York artists and one from each of the forty-four states, plus Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Panama Canal, and the Virgin Islands. In addition to Hutchinson, the New York artists were Alexander Archipenko, Gifford Beal, Arnold Blanch, Lucile Blanch, Ann Brockman, Charles E. Burchfield, C.K. Chatterton, Jon Corbino, John Edward Costigan, Arthur Dove, Guy Pène du Bois, Louis Eilshemius, John Flannagan (sculptor), Donald Forbes, Emil Ganso, William Glackens, Harry Gottlieb, Edward Hopper, C. Paul Jennewein, Mrs. Georgina Klitgaard, Walt Kuhn, Sidney Laufman, Ernest Lawson, Jonas Lie (painter), Luigi Lucioni, Henry Mattson, Henry Lee McFee, Hobart Nichols, Georgia O'Keeffe, Henry Varnum Poor (designer), Ellen Emmet Rand, Charles Rosen, John Sloan, Eugene Speicher, Maurice Sterne, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Carl Walters, and Heinz Warneke.[67]

- Devree said the exhibition took place "at the Barbizon." When critics said an exhibition took place "at the Barbizon" they meant the Barbizon-Plaza Hotel. Completed in 1930 the Barbizon-Plaza Hotel at Central Park South between Sixth and Seventh Avenues was an apartment, or residential hotel. It aimed to attract artists, musicians, actors, and other members of the arts community by offering inexpensive rooms and providing studios, concert halls, and similar amenities. Its art gallery, adjacent to a mezzanine, was sometimes called the Mezzanine Gallery (or Galleries).[69][70][71] In its advertising, the hotel referred to the gallery as the "Barbizon Petit Palais des Beaux Arts."[72] In the late 1930s the management served after-dinner refreshments in the mezzanine and provided quiet music so guests could sit and observe the lobby below or move about in the adjacent gallery where, its advertising stated, "exhibits of leading European and American artists are shown monthly."[73] The Barbizon-Plaza had a sister hotel, the Barbizon Hotel for Women completed in 1928 and located at 63rd Street and Lexington Avenue. It was also an apartment hotel, but where the Barbizon-Plaza accepted both men and women residents (after considering the references they submitted) the older Barbizon was restricted to women (also accepted only after review of references). In news reports and reviews, like Devree's, either hotel could be called simply "the Barbizon." Readers were expected to understand that when the article referred to an art exhibition the building meant was the Barbizon-Plaza. The Barbizon Hotel for Women had a lounge in which concerts could be performed and it had studios adapted for the use of artists and musicians. It also had a mezzanine in which pictures could be displayed. However it had no art gallery and almost all its public spaces, apart from the lobby, were restricted to women only or, in rooms where men were allowed, a permit had to be obtained.[74]

- A critic for the New York Sun, writing in 1938, had failed to recognize that the woman was white.[76] The reporter who interviewed Hutchinson in 1940 wrote: "Rather than painting with a full value range and giving a photographic reproduction, Miss Hutchinson concentrates on arriving at a sculpturesque fullness. She limits third dimension deliberately and thereby intensifies her designs. The canvasses for which she has most affection are built around abstract qualities like 'Sleep' and 'Racial Prejudice.' And speaking of the latter, the picture reproduced here [i.e., 'The Duet'] won a prize, but, Mary suspects, without the judges knowing its real subject. Ostensibly a youth and girl are working over some music. He holds the violin and she the score. The judges thought they were two negroes. But Mary says she may have overdone the sun-tan on the girl's face. Actually she is a white girl. And the picture is supposed to say that through the arts racial barriers are eliminated. She is not advocating intermarriage, just a bit of tolerance and working together."[10]

- While nothing is known of her other African American subjects, the model for "The Composer" and "The Composer at His Keyboard" was well known. His name was Luke Theodore Upshure. The son of a former slave, he was born in 1885 and was educated at Columbia University, City College of New York, and Cooper Union. Although he earned a living as a janitor in a Greenwich Village apartment building, his real vocation was music. He taught piano and composed solo and orchestral music. He and his wife, Anne McVey (who was white), gave parties which were famous in their time for music, poetry, and political discussion. In an invitation to a party held May 6, 1934, Upshure wrote: "Please, come rest, meditate, make merry a while among friends in an atmosphere of tranquility far removed from the chaotic muddled world with its ghastly hypocrisies and eternal stupidity. It is my desire to give you a musical feast with wholesome music, just a sip of nectar before we are hurled back to the alcoves of the unknown."[81] The American sculptors Arthur Lee and Augusta Savage made busts of him and his portrait was painted by the German, Walter von Ruckteschell, the Frenchman, H.L. Laussucq, and the Austrian, Walter Carnelli, as well as by Hutchinson.[82][83][84]

- La Maison Française was built in 1932 in Rockefeller Center by U.S. and French interests to showcase French commercial exports and culture.[87] A reviewer for the New York Times said the 1938 exhibit contained pictures appropriate to the exhibition's theme: "The pictures ruthlessly expose the evils of old and inadequate housing, crowded tenements and streets, and the miseries of the poor and the unfortunate who are packed together under inhuman conditions."[86]

- A group of six artists established An American Group Inc. in the summer of 1931. It was a cooperative organization which held exhibitions of work by young artists who were not able to obtain representation by the major commercial galleries. In the early part of the decade it held its shows exclusively in the Barbizon-Plaza Hotel and later used a succession of different galleries.[88][89][90][91]

- Hutchinson was a member of the Board of Directors of the Society of Independent Artists in the early 1940s.[78]: 384 When interviewed in 1940 she said she strongly believed in the policies of the Independents: "They are the only truly democratic organization in America. And have been the first showing place of so many excellent painters... We've got to take art out of the luxury class and make it vital to every day life."[10] (The reporter gave the society's name as "Independent Painters and Sculptors of America, but gave the society's address correctly.)

- The League of Present Day Artists was an outgrowth of the Bombshell Artists Group. The latter had come into existence in 1942 at the instigation of an art critic and gallery owner, Samuel M. Kootz. In 1941 Kootz had written an inflammatory letter to the New York Times in which he said American artists were overly timid and the times were ripe for a "fresh impulse" to produce a style that displays individuality and that is "vigorous, healthy, and more suitable to his [i.e., the artist's] contemporary ideas."[93][94] In 1944 the Bombshell Group changed its name to the League of Present Day Artists. The league, like the Bombshell Group, held Annual exhibitions at the Riverside Museum. Artists, particularly painters, sculptors, and printmakers who were "working along new trends in art," were invited to submit works for jury evaluation.[95] and new members were admitted by ballot of all existing members after review of three works.[94][96] In 1947 its chairman, Leo Quanchi, described the group as a "progressive group of modern painters and sculptors involved in the unselfish purpose of cooperation and assistance to its fellow men and women in the arts, with aims to uncover and bring to the fore new talents otherwise lost in the maelstrom of economic pressure and indifference."[97]

- In 1950 her work appeared in two solo exhibitions in Atlanta, the Castle Gallery and the West Hunter Street Library.[78]: 401

- The community art center was part of the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration. Beginning in 1935 the FAP employed out-of-work instructors to teach art in community centers within American cities. Hutchinson's position was technical supervisor of the Art Teaching Staff at the Harlem Community Art Center.[8]: 166 The WPA/FAP Art Teaching Division employed teachers to give free art classes to children and adults in community centers such as the one in which Hutchinson worked.[101] In 1936 she gave lectures at a gallery in Macy's department store on "Picture Making by Children" displaying pictures that the children created in these classes.[100]

- Both sets of Hutchinson's grandparents had been born in New England (three in New Hampshire and one in Vermont).[108]

- Merrill Hutchinson graduated from the University of Vermont in 1895. While a student there he had served as organist in the university chapel.[113] In 1898 he began work as the principal organist in Christ Episcopal Church.[114] He moved to New York in 1902 to serve as assistant organist at South Church, a Reformed Dutch Church on Madison Avenue at 38th Street, and to study at the Guilmant Organ School, First Presbyterian Church.[103][115][116] In 1904 he started as assistant organist at St. George's Episcopal Church on Stuyvesant Square.[112][114]

- After moving to Atlanta Merrill became organist at St. Luke's Episcopal Church. At that time both parents taught at the Woodberry School for Girls, Merrill as director of music and piano instructor and Minnie Belle as instructor of voice culture and dramatic expression.[114][117][118][119][120] Before her marriage to Merrill, Minnie Belle lived in Boston, studying at the Emerson School of Oratory and teaching elocution to clergymen and other public speakers.[109][120] Sometime between 1910 and 1914 Merrill left the school to study in Germany and in 1915 returned to Atlanta where he became the organist at First Church of Christ, Scientist and opened a studio to teach keyboard music and pursue a career as concert organist.[121][122][123] While he was away Minnie Belle left the Woodbury School to become acting director of the department of Expression and Dramatic Arts at a boarding and day school for girls called Washington Seminary.[124][125]

- The Washington Seminary was a co-educational day school founded in 1878 by two nieces of George Washington. In 1953 it merged into The Westminster Schools.[124]

- In 1922 singles tennis competitions, Hutchinson won the Atlanta Y.W.C.A. championship and was runner-up in the Georgia State Tournament. She told a reporter she had begun playing in 1919 in matches with her father and not long after was able to win the tournament at Washington Seminary.[130]

- Hutchinson's academic performance was evidently not very good since she was listed in the school catalog as a freshman both years. She was said to have spent three years at Agnes Scott College but evidence of a third year is lacking.[10][133][134] As previously noted, she told interviewers that she flunked the school's art course.[9][10]

- Examples of the three versions of Hutchinson's name are given in references to this article.

References

- "Mary E Hutchinson, 10 Jul 1970". "Georgia Death Index, 1933-1998," database, FamilySearch; citing Fulton, Georgia, certificate number 022672, Georgia Health Department, Office of Vital Records, Atlanta. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- Turner, Jae. "Mary E. Hutchinson". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- "Mary E. Hutchinson and Dorothy King papers, 1900-1988". Emory University Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. Atlanta, GA. 20 August 2008. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- Howard Devree (1935-05-19). "A Reviewer's Notebook: Exhibitions of Water-Colors; Slimmer Shows of Work by Women". New York Times. p. X9.

- "One-Man Shows in Many Galleries—Group Exhibits and Other Interesting Art Events". New York Evening Post. 1932-11-26. p. 8.

Mary E. Hutchinson's "Rosalie" is excellently held to linear arabesque with bold yet rhythmic design; her other canvases are too much inclined to be assertive in color and pattern.

- Howard Devree (1933-03-05). "The Week in the Galleries: Art in Her Infinite Variety". New York Times. p. X8.

Mary E. Hutchinson form a show of contrasts at the Painters and Sculptors Gallery. Miss Hutchinson's portraits emerge from her other work. She has infused them with a haunted mood and they are instinct with sympathy. The convalescent girl in her mean little room is effective emotional overtone.

- Howard Devree (1934-02-08). "A Developing Talent". New York Times. p. 17.

Pictures by Mary E. Hutchinson, chiefly portraits, have been easily identifiable in various group exhibitions in which they have appeared, one or two at a time, through several seasons. The current one-man show of her recent work at the Midtown Galleries furthers the impression of a steadily developing individual talent. From her early training she carried into her painting a sculptural quality. A striking sense of design is implicit in her work. Subtler use of color is coming. Faces of the portrait subjects retain an almost morbidly brooding sensitiveness, as in Miss Hutchinson's first paintings; but her maturing talent has in other respects found expression less introspectively.

- Harris, Jonathan (1986). The New Deal Arts Projects: A Critical Revision: Constructing the "National-Popular" in New Deal America 1935-1943 (PDF) (Ph.D.). Middlesex University Research Repository. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- "Off-Project Work". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1937-12-05. p. 33.

- Willa Gray Martin (1940-03-24). "Mary Hutchinson of Atlanta, Whose Paintings Have Won Numerous Prizes, Failed in Art Course at College". Herald-Journal. Spartenburg, Ga. p. 12.

- "School of Design Awards Honors". New York Times. 1928-05-06. p. 29.

Women's Night Class—Figure—Suydam bronze medal, Joan Starr, Mary Hutchinson

- "Academy of Design Awards Art Prizes". New York Times. 1930-04-30. p. 52.

Etching Class: ... Honorable Mention, Virginia Snedeker, Mary Hutchinson, and Dorothy Drew.

- "National Academy School Prizes". National Academy. 9: 93–94. 1889. JSTOR 25608109.

Two classes of Medals are offered for competition in the Academy schools, and "Honorable Mention" is accorded to students making marked progress. The Elliott Medals, of silver and bronze, are awarded to the two students making the best drawings from the Antique. The Suydam Medals, also of silver and bronze, are given to the two students who attain the highest degree of proficiency in the Life school. In each class, all the competitors for prizes make their drawings at the same time, from the same model.

- "Academy of Design Announces Awards". New York Times. 1926-05-05. p. 24.

- "Design Academy Gives Art Prizes". New York Times. 1933-05-03. p. 13.

- "Ex '29". Agnes Scott Alumnae Quarterly. Decatur, Georgia: Agnes Scott Alumnae Association: 37. January 1926. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

Mary Elizabeth Hutchinson is a student at the National Academy of Design in New York City. Her address is 518 W. 111th St., Apt. 65. She has won quite a bit of recognition at the school.

- "Artworks of Mary E. Hutchinson—Hutchinson Biography". An on-going project by Jae Turner to develop a digital catalog of Mary E. Hutchinson's work. Archived from the original on 2016-02-26. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- "Four Artists Show New Work; Mary Hutchinson Exhibits at Midtown". New York Sun. 1934-02-14. p. 14.

Mary E. Hutchinson, who is exhibiting at the Midtown Galleries, is enamored of form, and she gets it at all hazards. From her early training in sculpture one would expect her to be inclined "to see in the round," and perhaps she does, but if a contour seems to be in danger of being lost, she does not hesitate to reinforce it by resorting to the convenient decorative convention of a hard outline. The contour is preserved, but all suggestion of an enveloping atmosphere is lost. All of which is doubtless quite as it should be if you prefer things that way, and Miss Hutchinson apparently does. Some do not, and value a bit above a bald statement.

- "Work by a New Group". New York Times. 1932-02-25. p. 19.

...Mary E. Hutchinson's carefully abstracted "Edgewater Basin"...

- Edward Alden Jewell (1932-05-07). "G.R.D. Studio". New York Times. p. 21.

...excellent little gallery at 58 West Fifty-fifth Street, operated through the courtesy of Mrs. Philip J. Roosevelt, mainly as a forum for young and unknown artists.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1932-10-25). "New Gallery Opened by the G.R.D. Studio Has Large Group Exhibition Representing Its First Four Years". New York Times. p. 22.

- "The G.R.D. in New Quarters". New York Sun. 1932-10-29.

- "At the Jumble Shop". New York Times. 1933-12-21. p. 17.

The Jumble Shop...has for some time concerned itself with more than just the serving of food. It served art as well, in a series of informal exhibitions which are open to the public all day... The proprietors are Miss Frances E. Russell and Miss Winifred J. Tucker.

- "Jumble Shop Exhibits American Artists' Work". New York Sun. 1932-02-06. p. 8.

The Jumble Shop, at 28 West Eighth street, one of the oldest restaurants in the Washington Square section, has begun giving exhibitions of pictures by American artists, a new show to be hung on the first of each month. Guy Pene Du Bois, H.E. Schnakenberg and Reginald Marsh form the committee to select the work, and Mrs. William Bradford Robbins will collect and arrange the shows.

- "Artworks of Mary E. Hutchinson | Exhibitions". An on-going project by Jae Turner to develop a digital catalog of Mary E. Hutchinson's work. Archived from the original on 2016-02-26. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- R.E.R (1932-05-23). "I've Been Thinking". Long Island Daily Press. Jamaica, N.Y. p. 8.

The venture, according to Vernon Porter, head of the committee, will be "an absolutely non-commercial plan," except for the profits that may result to needy artists. There will be no entrance fees and no dues or other charges to the exhibitors.

- "Sidewalk Art Sale Approved by City; Police Grant Permit for Show in Washington Square to Aid Artists Out of Work". New York Times. 1932-05-21. p. 17.

There will be no entrance fees and no dues or other charges to the exhibitors. Each exhibitor will be required to bring his own work, remain in charge while it is on display and move it at the end of the day... Dealers will not be permitted to exhibit or sell unless representing artists who cannot be present.

- "Artists Sell 48 Paintings for $360 In Washington Sq. Sidewalk Show: Throngs in Street Inspect Works Propped Against Fences and Steps on First Day of Open-Air Sale — One Needy Artist, After Two Sales, Goes Home to Pay Rent". New York Times. 1932-05-29. p. N1.

Each artist had approximately ten feet in which to show his work... Many types of work were displayed. The lion of modernism was exhibited calmly beside the quiet work of those taking their lead from the academicians. There were modern designs which evidently meant little to the average passer-by but which seemed to hold interest.

- "Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibition". Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- "Calendar of Current Art Exhibitions in New York". Parnassus. 5 (2): 30–31. February 1933. doi:10.1080/15436314.1933.11466373. JSTOR 770731.

A group of painters and sculptors calling themselves simply "An American Group" has taken over the art gallery which was optimistically built into the Barbizon-Plaza several years ago. The avowed purpose of the organization is: "a mutual cooperation in furthering the artistic welfare of its members and to endeavor to interest the wide public in the activities of the contemporary American Art and Artists."

- Marion Clyde McCarroll (1931-07-16). "Young Painter Plans New Gallery for Mutual Benefit of Artists and Public; Pictures to Sell at Small Prices for Little Homes; Place Will Open on Eleventh Street November First". New York Evening Post. p. 6.

...the idea is to benefit both those who want good pictures and pieces of sculpture in their homes but have not the means to buy them through the large established galleries, and the artists themselves who frequently find it difficult to get their work into the leading galleries...

- "Opens Art Salon". New York Sun. 1931-11-02. p. 50.

Miss Margit Varga, a twenty-three-year-old Hungarian painter, opened her cooperative art gallery yesterday at 22 East Eleventh street. Miss Varga hopes to bring the public and the aspiring but unknown artist together through her Painters and Sculptors' Gallery.

- "A Show of Honest Work". New York Times. 1933-03-09. p. 16.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1933-04-23). "Laurel Wreaths and Marching Ranks". New York Times. p. X8.

- "Art for Rent at This Hotel; New Weston Adopts Novel Idea for Hostelries". New York Sun. 1934-10-05. p. 4.

Particularly striking is the "Aria Trista," by Mary E. Hutchinson, a painting of a young girl and her violin. Miss Hutchinson, who has received favorable attention from critics, has two other canvases, "Radio City" and "Jane," in the show.

- "Howard Devree, Art Critic, Dead: Former Times Editor Was 76". New York Times. 1966-02-10. p. 37.

Mr. Devree became art critic on the death of Edward Alden Jewell on Oct. 11, 1947, and he retired in 1959, when his post was assumed by John Canaday... In 21 years with The Times before becoming art critic Mr. Devree served in the Sunday department, was an assistant to the art critic, and wrote book reviews and other stories in the cultural field.

- Howard Devree. "Summary of the Modern Babel: a study of confusion in the art world". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- "Some Recent Museum Acquisitions". Parnassus. 6 (4): 16. April 1934. doi:10.1080/15436314.1934.11466907. JSTOR 770731. S2CID 254670119.

Atlanta, Georgia, The High Museum of Art...Paintings, Two of Them and Italian Girl, by Mary E. Hutchinson (By purchase from the Midtown Galleries of New York)...

- "High Museum of Art". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- "Alan Gruskin, 65, of Art Gallery; Backer of Modern Trends in U.S. Painting Is Dead". New York Times. 1970-10-08. p. 50.

- "Detailed description of the Midtown Galleries records, 1904-1997". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- Howard Devree (1934-02-11). "Current Activity in a Group of Local Galleries". New York Times. p. X12.

Mary E. Hutchinson has peopled the Midtown Galleries with hauntingly introspective subjects... Individual without being sensational, Miss Hutchinson has, with excellent results, gone quietly on her way toward maturity.

- "Herman Baron, Art Patron, Dies: Founder of the ACA Gallery Started Careers of Many Painters in Depression". New York Times. 1961-01-28. p. 19.

- "Summary of the ACA Galleries records, 1917-1963 - Digitized Collection". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- "Art Galleries Open Season". New York Sun. 1934-09-15. p. 7.

Miss Hutchinson shows a variation on her usual exhibited work in the shape of two landscapes, one of which "Sixth Avenue L," is a solid and compactly organized canvas, marked by an expressive use of curves and soberly satisfying color. More in her usual sculpturesque vein are the several studies of heads and the large "Nude" previously shown with the independents. Outstanding in the group is the portrait of Margit Varga, in which there is a hint of a sensitive and elusive personality.

- "Holiday Shows of Art Abound". New York Sun. 1934-12-11. p. 19.

- "13 Women Receive Awards for Art". New York Times. 1935-01-03. p. 21.

- "$1,300 Prizes Given to Women Artists". New York Times. 1938-01-04. p. 25.

- Howard Devree (1935-01-06). "A Reviewer's Week". New York Times. p. X8.

- "Recently Opened Shows". New York Times. 1934-02-10. p. 13.

The Upstairs Gallery, 28 East Fifty-sixth Street, has changed its name to the Ten-Dollar Gallery ($10 representing the top price asked for works of art)...

- Howard Devree (1933-12-10). "Other Shows". New York Times. p. X12.

- "Summary of the Marguerite Zimbalist papers relating to Louis M. Eilshemius, 1880-1963". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- "Reinhardt Galleries". New York Post. 1937-10-16. p. 12.

- "Women". New York Times. 1935-02-10. p. X9.

- "New York Society of Women Artists Soon to Hold Exhibition". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1926-02-28. p. E7.

- "City Art Show Sets New Pace; Makes Its Best Showing Up to Present". New York Sun. 1936-05-22. p. 15.

- "New York Artists Show their Wares: Exhibition of Varied Work Is Put on Display at the Municipal Galleries". New York Times. 1939-05-24. p. 32.

- "Art Group Is Praised by Mrs. Breckinridge: Its Chairman Holds La Guardia Committee Has Earned Right to Financial Support". New York Times. 1936-04-18. p. 13.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1936-05-01). "Federal Project Opens Art Exhibit: Display of Graphic Creations Is Combined With Reception Attended by Mayor". New York Times. p. 17.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1936-05-20). "City Art Museum Offers 8th Exhibit". New York Times. p. 19.

- Jerome Klein (1936-05-02). "Artistic Oddities Obscured in Show by Independents annual show Grand Central Galleries". New York Post.

- Howard Devree (1935-10-22). "A New Gallery". New York Times. p. 19.

- Catalogue of the Forty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture (PDF). Art Institute of Chicago. 1936.

- Ian Chilvers (10 June 2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 661. ISBN 978-0-19-860476-1.

- "Show to Include Art of Hotel Waitress: Independents' jubilee Exhibit Will Open on Thursday". New York Times. 1941-04-12. p. 18.

- "War Fails to Stop Independents' Art: 27th Annual No-Jury, No-Prize Exhibition Opens... Active Officers Planned Show After Duties in War Plants—Prices Limited to $250". New York Times. 1943-05-05. p. 25.

For twenty-seven years the Society of Independent Artists has been one of the most democratic art organizations in the country, offering any artist, famous or unknown, an opportunity to exhibit his work to the public, without censorship by a jury of selection. Any work sent in by a member is hung. To insure fairness, the hanging is alphabetical, and no prizes are tolerated.

- "40 Artists Are Invited; Asked to Represent City and State at National Exhibition". New York Times. 1936-05-14. p. 23.

- Howard Devree (1937-02-14). "A Reviewer's Notebook: Brief Comment on More Than a Score of Current Shows in the Local Galleries". New York Times. p. 170.

Nearly ten years of progress is illustrated in the group of canvases by Mary Hutchinson (through Feb. 22) in the Mezzanine Gallery at the Barbizon. From the figure of 1929 to the just completed "Shine Boy" there is a series of steps toward simplification, sureness, subtler color values, inspired by a lively decorative sense. Portraits are unquestionably Miss Hutchinson's best work.

- "Barbizon-Plaza Hotel". NYC Organ Project. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- "Display Ad: Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Children". New York Times. 1936-10-18. p. 7.

- "Among the Other Shows: Prints". New York Times. 1939-03-12. p. 159.

- "Display Ad: One Knows Them by Their Habitat". New York Times. 1930-09-30. p. 33.

... viewing the worth-while art in the Barbizon Petit Palais des Beaux Arts located on the mezzanine... [in] a building dedicated to the privileged detachment of the cultivated mind.

- "New York Press Group to Visit Fair". Alfred Sun. Alfred, N.Y. 1939-05-25. p. 3.

- "Barbizon Hotel for Women" (PDF). Landmarks Preservation Commission: Designation List 454 LP-2495. 2012-04-17. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-09. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- "Some Drawings by the Masters; Other Group and One-man Shows Now Current". New York Sun. 1937-11-27. p. 12.

Mary Hutchinson, who is holding her first solo exhibition in several years at the Midtown Galleries, 605 Madison avenue, still seems primarily concerned with the sculpturesque possibilities of her subjects and in this regard continues to advance. "Duet" and "Student" are notable in this respect, as are the previously shown "Composer" and "Yun Gee." An escape from the carnations and subtle grays of the Caucasian coloring seem to help her greatly. Her portrait of Isobel Howe is an exception. In this she has got away from the tendency to blackness and hard contours evident in so much of her work. It seems quite the best thing in this line she has every shown, being pleasing in color and suavely painted.

- "American Women in Art". New York Sun. 1938-01-08. p. 12.

"The Duet," by Miss Hutchinson, which has the place of honor in the main gallery and is concerned with a young Negro man and woman lost in contemplation of a sheet of music, is boldly conceived, and from the point of view of dynamics easily dominates the entire room, but the two figures are so "posed" that they seem almost to have been frozen in to their positions.

- Margaret Breuning (February 1938). "Art in New York". Parnassus. 10 (2): 21–26. doi:10.2307/771820. JSTOR 771820.

[O]ne of the few startling canvases, Duet, by Mary E. Hutchinson, is one of the least commendable, for it hits you between the eyes at first viewing, but has nothing to say after this.

- Jae Turner (Summer 2012). "Mary E. Hutchinson, Intelligibility, and the Historical Limits of Agency". Feminist Studies. Feminist Studies, Inc. 38 (2): 375–414. doi:10.1353/fem.2012.0014. JSTOR 23269192. S2CID 149824187.

- "Art in a Sky Scraper". New York Times. 1939-02-05. p. RP7.

- Jae Turner. "Artworks of Mary E. Hutchinson". Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- "POSTSCRIPT: How One WIN Moment Changed Three Lives: Anne McVey Upshure's 94 Years of War Resistance". War Resisters League. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- Who's who in Colored America. Who's Who in Colored America Corporation. 1942. p. 526.

Upshure, Luke Theodore—Teacher of Pianoforte-Composer.

- Rachel Cohen (9 March 2004). A Chance Meeting: Intertwined Lives of American Writers and Artists, 1854-1967. Random House Publishing Group. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-58836-370-1.

- H Allen Smith (27 July 2015). Low Man on a Totem Pole. eNet Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-61886-878-7.

Luke Theodore Upshure was janitor of an apartment house on Waverly Place. He was an aging Negro with twisted, crippled hands but he was educated and something of an artist. He lived in the basement of the building where he worked and it was his custom to put aside all liquor bottles thrown out by the tenants until he had accumulated enough to sell to a junk dealer. With the money these bottles brought in Luke Theodore Upshure would then purchase liquor bottles with liquor in them and hurl a soiree.

- "Women Elect". New York Post. 1938-01-22. p. 19.

- "Slums Inspiration for Art Exhibition". New York Times. 1938-04-14. p. 21.

- "Rockefeller City Adds French Unit". New York Times. 1932-03-31. p. 23.

- Sterne, Katharine Grant (November 1931). "In the New York Galleries". Parnassus. 3 (7): 30–31. doi:10.2307/770690. JSTOR 770690. S2CID 193949749.

- "New Group Holds First Show". New York Times. 1931-10-20. p. 32.

An American Group, newly formed and duly established in the galleries of the Barbizon-Plaza, is holding its first exhibition.

- "New Art Group in First Display; Cooperative Society Shows at Barbizon-Plaza". New York Sun. 1931-10-23. p. 32.

An American Group, that adventurous little band who have leased their own galleries in the Barbizon-Plaza, are holding a first exhibition, which is to continue until November 14.

- Andrew Hemingway (2002). Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926-1956. Yale University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-300-09220-2.

- "Art in a Skyscraper". New York Post. 1939-02-11. p. 10.

- Samuel M. Kootz (1941-10-05). "'Bombshell' Clarified: Mr. Kootz Elaborates His Point of View, Pointing Up Issues in the Controversy". New York Times. p. X9.

- "Bombshell Artists Group". Forgotten Stories from the Art World annehyoung. 17 March 2013. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- "Art Notes". New York Times. 1944-04-14. p. 17.

- "Loew's Mayfair to Offer Art Exihbit Wednesday". New York Post. 1946-07-06.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1947-10-07). "Modernists' Art Shown at Museum: League of Present Day Artists Offers Display at Riverside". New York Times. p. 25.

- Howard Devree (1945-02-11). "A Reviewer's Notes". New York Times. p. X8.

- "Gallery Displays 18 Award Winners". New York Times. 1953-05-08. p. 23.

- "Macy's to Exhibit Children's Art". New York Sun. 1936-10-17. p. 20.

- Don Adams; Arlene Goldbard (1995). "New Deal Cultural Programs: Experiments in Cultural Democracy". Institute for Cultural Democracy. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- Franklin Miller Garrett; Harold H. Martin (15 April 2010). Atlanta and Environs, Vol. 3. University of Georgia Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8203-3136-2.

- "Merrill M Hutchinson in household of Percey W Bailey, Montpelier city Ward 1 & 6, Washington, Vermont, United States". "United States Census, 1900," database with images, FamilySearch; citing sheet 3B, family 74, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,241,695. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- "Merrill M Hutchinson, 12 Jun 1945". "Georgia Death Index, 1933-1998," database, FamilySearch; citing Fulton, Georgia, certificate number 11787, Georgia Health Department, Office of Vital Records, Atlanta. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- "Mary Elizabeth Hutchinson, 11 Jul 1906". "Massachusetts Births, 1841-1915," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Melrose, Massachusetts, reference p 581, Massachusetts Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 2,315,131. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- "Guide to the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Commission on Ecumenical Mission and Relations. Secretaries' files: Mexico Mission". Presbyterian Historical Society. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

In 1872, the General Assembly [of the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A] voted to establish a formal mission in Mexico, building upon the work of these earlier leaders. The Board appointed the Reverend and Mrs. Henry C. Thomson, the Reverend and Mrs. Maxwell Phillips, the Reverend Paul Henry Pitkin, the Reverend and Mrs. Merrill N. Hutchinson and Miss Ellen P. Allen as its first missionaries.

- "Gonzales Inauguration; Brilliant Reception of the New President of Mexico at the Capital". World [Newspaper]. New York, N.Y. 1880-11-30. p. 3.

The family of the Rev. Merrill Hutchinson will leave Mexico in the next steamer. Their departure will be deeply regretted by the English and American colonies and is regarded by the Mexican Protestants as an absolute calamity. During the eight years for which Mr. Hutchinson has had charge of the Presbyterian Missions in Mexico he has been a zealous and indefatigable worker; has made reforms innumerable, and leaves the mission churches and schools throughout that portion of the Republic which was under his jurisdiction in a most flourishing condition. Owing to the delicate health of Mrs. Hutchinson and the necessity of a change of climate for two of his children, Mr. Hutchinson has asked the Board of Missions to grant him leave of absence for two years and proposes spending a portion of his vacation in Europe.

- "Minnie Belle Hutchinson in household of Merrill M Hutchinson, Atlanta Ward 8, Fulton, Georgia, United States". "United States Census, 1920," database with images, FamilySearch; citing sheet 18B, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,820,253. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Merrill M. Hutchinson and Minnie Belle Bradford, 20 Sep 1905". "Massachusetts Marriages, 1841-1915," database with images, FamilySearch; citing pg. 623 cn 115, Boston, Massachusetts, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 2,057,622. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Hutchinson, 15 May 1908". "Massachusetts Deaths, 1841-1915," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Melrose,,Massachusetts, 383, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 2,257,165. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Madeline Hutchinson, 13 Oct 1907". "Massachusetts Deaths, 1841-1915," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Melrose,,Massachusetts, 315, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 2,217,233. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "St. George's Church". The New York City Organ Project. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- Charles Spooner Forbes; Charles R. Cummings (1903). The Vermonter: The State Magazine. C.S. Forbes. p. 35.

- Lloyd's Church Musicians' Directory (1910): The Blue Book of Church Musicians in America. Ritzmann, Brookes & Company. 1910. p. 51.

- "South Reformed Dutch Church". The New York City Organ Project. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- "Christmas Music in the Churches". New York Herald. 1902-12-21. p. 16.

Miss Woodberry's music and expression department of Miss Woodberry's school forms one of the finest musical centers of instruction in the state. She has secured Professor Merrill Hutchinson, for piano, formerly organist of St. George's, New York, now organist of St. Luke's, Atlanta; Miss Nance B. Martin, formerly of the faculty of the Cincinnati College of Music, who will teach voice; Mrs. Theodora Morgan Stephens, for years a student under German masters in Berlin, for violin; and Mrs. Merrill Hutchinson, of the Emerson School of Expression, who has trained many clergymen and public speakers in voice culture and dramatic expression.

- "Merrill Hutchinson in household of Rosa L Woodberry, Atlanta Ward 6, Fulton, Georgia, United States". "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 93, sheet 2B, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,374,205. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Correspondence: Atlanta". Musical Courier. New York, N.Y. 47 (15): 45. October 7, 1908.

- Homer L. Patterson (1917). Patterson's American Educational Directory. Educational Directories. p. 592.

- "Some Brilliant Educational Work". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Ga. 1909-08-22. p. 5.

- "Kraft Gives Final Concert in Atlanta". Musical America. New York, N.Y. 22 (23): 28. October 9, 1915. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

The return to Atlanta of Prof. Merrill Hutchinson is being welcomed. Professor Hutchinson, a pupil of Busoni, was formerly organist at St. Luke's Cathedral here. He resigned to study in Germany.

- "Professor Merrill Hutchinson, Former St. Luke's Organist, Has Returned to Atlanta". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Ga. 1915-09-26. p. 8.

Professor Merrill Hutchinson who will be well and favorably remembered as the organist at St. Luke's cathedral until he resigned to return to Germany and perfect himself in his profession has returned to Atlanta and established a studio at No. 15 West Eleventh street. Professor Hutchinson who was a pupil of Busoni, is recognized as one of the leading pianists and organists of America. He is open to regular or special employment for occasions and is now organizing classes for the piano during the fall and winter months at his studio.

- "Variations on Musical Themes Southeast". Musical Courier. New York, N.Y. 72 (15): 21. April 13, 1916.

- "Washington Seminary". Westminster Schools. Archived from the original on 2014-11-05. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- "Washington Seminary; Important Announcement". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Ga. 1917-09-09. p. 6.

Mrs. Merrill Hutchinson, one of the foremost teachers of expression in Atlanta, will have charge of the department of Expression and Dramatic Arts during the leave of absence of Mrs. Rosalind Mitchell Lunceford, who is spending half a year in New York for study at Columbia University.

- "Minnie B Hutchinson in entry for Merrill W Hutchinson, 1930". "United States Census, 1930", database with images, FamilySearch. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Minnie B Hutchinson in household of Merrill M Hutchinson, Ward 5, Atlanta, Atlanta City, Fulton, Georgia, United States". "United States Census, 1920," database with images, FamilySearch; citing sheet 18B, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,820,253. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Miss Hutchinson Gives Recital". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Ga. 1923-05-04. p. 11.

- "Trophy Winners in State Net Tourney". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Ga. 1921-10-14. p. 11.

- Leonora Anderson (1922-10-29). "Miss Mary Hutchinson". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Ga. p. 6.

Miss Mary Elizabeth Hutchinson winner of the tennis cup of the Y.W.C.A. tournament this year and the runner up in the Georgia State tournament—also this year—tell us that nothing can touch tennis. "I started playing with my father," this young champion of the racquet told me, "just three years ago, and I love it better than anything." No wonder Miss Hutchinson loves tennis. We mortals usually love the thing which we do well, and this pretty student at Washington Seminary has had many victories and honors won by her playing.

- "Freshman Class Roll and Student Directory". Silhouette. Decatur, Georgia: The Students of Agnes Scott College. 21: np. 1924. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

Hutchinson, Mary Elizabeth, 15 West 11th St., Atlanta, Ga.

- "Freshman Class Roll and Student Directory". Silhouette. Decatur, Georgia: The Students of Agnes Scott College. 22: np. 1925. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

Hutchinson, Elizabeth, 15 West 11th St., Atlanta, Ga.

- "Georgia Girl Exhibits Work". Evening Recorder. Amsterdam, N.Y. 1934-03-12. p. 12.

Mary. E. Hutchinson, young Georgia artist, exhibited a representative collection of her work in a New York gallery. Miss Huchinson attended the Agnes Scott college near Atlanta for three years before journeying north to study at the National Academy. New York critics believe she will be one of our outstanding portrait painters.

- "Freshman Class Roll and Student Directory". Silhouette. Decatur, Georgia: The Students of Agnes Scott College. 23: np. 1926. Retrieved 2016-01-30.