Mary Hutton (poet)

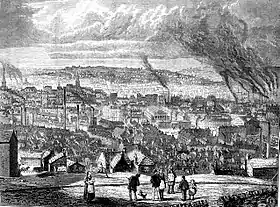

Mary Hutton was an English labouring class writer from Yorkshire. Born in Wakefield on 10 July 1794, she moved to Sheffield when young and spent most of her life there. She was the author of three poetry collections, the last of which was a miscellany of prose and verse.

Early life 1794-1831

In the preface to her third collection, Mrs Hutton, born Mary Taylor, relates how she was a twin and the only one in a family of twelve children to suffer from scurvy. When her family moved to London, Mary's health forced her to remain in Wakefield. Some years later, she left for Sheffield and there met and married Michael Hutton, a cutler some twenty-five years older with two children from a previous marriage. Her husband was in poor health and later on found he had been defrauded by the Benefit society to which he had been paying contributions.[1]

Needing to contribute to their finances, Hutton wrote a letter in 1830 to John Holland, a prominent city author, appealing for help in publishing a volume of her poetry. Holland agreed to raise subscriptions on her behalf and records, in the preface he wrote for it, how he decided to meet Mary in person. He found her living in Butcher's Buildings, Norris Field, "the wife of a pen-knife cutler, whose lot, it seems, had constituted no exception to the occasional want of employment and paucity of income, so common with many of his class."[2] Titled Sheffield Manor and Other Poems, the bulk of the pieces there are of the descriptive, topographical kind such as Holland himself had composed at his debut. Early publicity emphasised Mary’s status as "wife of a poor pen-knife cutter in Sheffield".[3]

A radical poetic

By the time of the preface to her next collection, The Happy Isle (1836), Hutton acknowledged labouring class support in the city "from a number of very respectable and worthy Mechanics, who think that they discern in my writings sufficient merit to justify their presentation to the world". But, she continued, she would have preferred to publish in its place a four-canto narrative poem set in the time of Henry VIII and titled "Sir Hubert de Vere".[4] Though some shorter narratives do appear in the book, contemporary issues are also highlighted. These include an outbreak of cholera, the new Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, and "A factory girl and her father", a consideration of child labour in which Hutton contrasts British interference abroad with a national blindness to domestic issues.

- Britons! inconsistent ever,

- Tell us why ye cross the main,

- The chains of Africa to sever,

- Whilst slaves your native babes remain?

Another poem deals with a widely reported case "of a poor girl who was taken before a Magistrate for weeping over her father's grave" - which, said a Scottish commentator in Tait's Magazine, "must surely be a new misdemeanour in England".[5] Meagan Timney has commented on the political stance she takes that "Hutton’s poems on the Poor Law and poverty are strikingly aligned with the poetry of the Chartist movement in both her appropriations of images of slavery and her use of discourses on human rights and freedom".[6]

The master theme is already announced in Hutton's title poem, "The Happy Isle", in which she presents a Utopia which is the obverse of the present:

- No baneful workhouses were there;

- The rich were not alone protected;

- Nor yet the poor sold and dissected;

- No prisons for pale infancy.

The third line quoted here takes up another item reported at the same time as the girl arrested for weeping at her father’s grave. In this case a parish overseer "had recommended a poor woman to sell the body of her child to the surgeons when she had applied to him for the means to bury it".[7] Such were the results of the new poor law that Hutton and many other radical contemporaries were deploring. But even when dealing with a literary theme, as in "On reading Childe Harold's Pilgrimage", she tempers her sincere praise by going on to extend Byron's radical views into consideration of modern social issues in France and England. A further foreign theme, the suppression of the Polish November uprising, is carried forward into her next work too, Cottage Tales and Poems (1842).[8]

On 4 March 1844, the Sheffield social campaigner, Samuel Roberts, and the poet, James Montgomery, published an open letter in a Sheffield newspaper entitled "The case of Mrs Mary Hutton".[9] This letter detailed the plight of Mary Hutton and her husband, who had been.. "thrown into great difficulties.....his wife, who detested and publicly denounced, in verse, the dreadful New Poor Law, was of too independent a spirit to apply to it for relief. They struggled on but the struggle was too much for them both; their strength, their health, and, at length, HER reason gave way. Her husband was then compelled to apply for her to the Workhouse, while he himself was admitted as an in-patient of the Infirmary". In 1843 Mary was sent to Attercliffe Asylum, which had recently been the subject of an enquiry into the forced restraint of inmates. The letter continues "There she remained during two weeks of such dreadful sufferings, that had they been longer continued, they must, she says, have precluded all hope of recovery". Mary was then sent to the Wakefield Asylum, "a change as she states, almost resembling a removal from hell to heaven". Mary was in the Wakefield Asylum for four months and recovered under the care of a Dr Corcellis and his wife. The letter reproduces a poem Mary had written to Dr and Mrs Corcellis

To you, ye worthy, noble-minded pair Devoted love and gratitude I owe; For your exalted skill and timely care Uprais'd me from the lowest depths of woe When in a storm of wild convulsions toss'd, My health and strength and blessed reason lost, And where I scarce could know my depth of pain Through the wild whirlings of a fever'd brain, Angelic tones fell softly on my ear, And sweetly soothed, and bade me banish fear, And cheered my poor desponding soul with love, And bade me hope and trust in heaven above.

The letter concludes that as of 19 January 1844, Mary has "been returned to Sheffield, about three weeks....(and husband and wife) are now living, in a very feeble state, with an only daughter, who has nothing but what she herself can earn to live upon.... Any persons wishing to afford relief, may forward their contribution to either of those whose names appear below, who will take care that all which is in any way contributed, shall be properly applied. SAMUEL ROBERTS. JAMES MONTGOMERY."

Death and later reputation

In the 1851 census entry, she is listed as a widow aged 59 and her occupation is given as "Poetess."[10] John Holland later recorded that she died in Sheffield's Shrewsbury Hospital in the spring of 1859.[11]

The poet has now been identified as an important figure in 19th century political writing by Ian Haywood in The Literature of Struggle: An Anthology of Chartist Fiction (1995), in which she is identified as "the only woman author of Chartist Fiction." More recently, John Goodridge’s Nineteenth-Century English Labouring-Class Poets: 1800–1900 (2005) collected five of Hutton’s poems[12] and Meagan Timney has explored her radical poetics.[13]

Notes

- Cottage Tales and Poems, 1842, pp. iii-iv, viii-ix

- Sheffield Manor and Other Poems (1831), p.ix

- The Monthly Review, no.2, p.324

- "University of California, Davis". Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Vol.3, p.335

- Meagan Timney, "Mary Hutton and the Development of a Working-Class Women’s Political Poetics", Victorian Poetry, Volume 49, Number 1,2011

- The New Monthly Magazine, 1835, "Tender Mercies" p.504

- Google Books

- The National Archives, MH 12/15467, Sheffield 582, 1843-1844, Correspondence with Poor Law Unions and other Local Authorities

- Meagan Timney, "Mary Hutton"

- William Hudson, The life of John Holland of Sheffield Park, 1874, p.156

- Pages 25-38

- “Mary Hutton and the Development of a Working-Class Women’s Political Poetics”,

References

- John Holland, “Mary Hutton”, The Poets of Yorkshire (1845) pp.224-6

- Meagan Timney, “Mary Hutton and the Development of a Working-Class Women’s Political Poetics”, pp. 127-146