Mary Richardson

Mary Raleigh Richardson (1882/3 – 7 November 1961) was a Canadian suffragette active in the women's suffrage movement in the United Kingdom, an arsonist, a socialist parliamentary candidate and later head of the women's section of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) led by Sir Oswald Mosley.

Mary Richardson | |

|---|---|

by Special Branch c. 1912 | |

| Born | 1882/3 |

| Died | 7 November 1961 Hastings, East Sussex, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Known for | Slashing the Rokeby Venus |

Life

She grew up in Belleville, Ontario, Canada. In 1898, she travelled to Paris and Italy. She lived in Bloomsbury, and witnessed Black Friday.[1]

Richardson was a noted writer who published a novel, Matilda and Marcus (1915), and three volumes of poetry, Symbol Songs (1916), Wilderness Love Songs (1917), and Cornish Headlands (1920).[1]

Richardson's Militant actions

At the beginning of the 20th century, the suffragette movement, frustrated by a failure to achieve equal voting rights for women, began adopting increasingly militant tactics. In particular, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), led by Emmeline Pankhurst, frequently endorsed the use of property destruction to bring attention to the issue of women's suffrage. Richardson was a devoted supporter of Pankhurst and a member of the WSPU. Richardson joined Helen Craggs at the Women's Press shop and told her of the abuse from men (obscene remarks) and customers tearing up materials.[2]

Richardson claimed to be at the Epsom races on Derby Day, 4 June 1913, when Emily Davison jumped in front of the King's horse. Emily Davison died in Epsom Cottage Hospital; Mary Richardson was reportedly chased and beaten by an angry mob but was given refuge in Epsom Downs station by a railway porter.[3][4]

She committed a number of acts of arson, smashed windows at the Home Office and bombed a railway station. She was arrested nine times, receiving prison terms totalling more than three years.[5][4] She was one of the first two women force-fed and released to recover and be re-arrested under the 1913 Cat and Mouse Act, Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913, serving her sentences in HM Prison Holloway.[1]

Richardson had been given the Hunger Strike Medal 'for Valour' by WSPU.

Richardson would recover at the cottage of Lillian Dove-Willcox in the Wye valley. She was devoted to Dove-Willcox and wrote poetry about her love for her.[6]

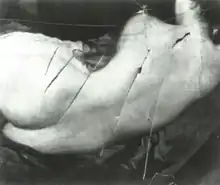

Damaging the Rokeby Venus

.jpg.webp)

An act of defiance by Richardson occurred on 10 March 1914 when she entered the National Gallery in London to attack a painting by Velázquez, the Rokeby Venus, using a chopper she smuggled into the gallery.[8] She wrote a brief statement explaining her actions to the WSPU which was published by the press:[9]

"I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas. Mrs Pankhurst seeks to procure justice for womanhood, and for this she is being slowly murdered by a Government of Iscariot politicians. If there is an outcry against my deed, let every one remember that such an outcry is an hypocrisy so long as they allow the destruction of Mrs Pankhurst and other beautiful living women, and that until the public cease to countenance human destruction the stones cast against me for the destruction of this picture are each an evidence against them of artistic as well as moral and political humbug and hypocrisy."

— "Miss Richardson's Statement". The Times. London. 11 March 1914.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unionist | Harry Brittain | 10,208 | 49.9 | −23.4 | |

| Labour | Mary Richardson | 5,342 | 26.2 | −0.5 | |

| Liberal | Neville Dixey | 4,877 | 23.9 | N/A | |

| Majority | 4,866 | 23.7 | −22.9 | ||

| Turnout | 20,427 | 67.1 | +13.2 | ||

| Registered electors | 30,425 | ||||

| Unionist hold | Swing | −11.5 | |||

As a fascist

In 1932, after forming the belief that fascism was the "only path to a 'Greater Britain,'" Richardson joined the British Union of Fascists (BUF), led by Sir Oswald Mosley. She claimed that "I was first attracted to the Blackshirts because I saw in them the courage, the action, the loyalty, the gift of service and the ability to serve which I had known in the suffragette movement".[11] Richardson rose quickly through the BUF ranks and by 1934 was Chief Organiser for the Women's Section of the party. She left within two years after becoming disillusioned with the sincerity of its policy on women.[12]

Two other prominent suffragette leaders to gain high office in the BUF were Norah Elam[13] and Commandant Mary Sophia Allen.[14]

Later life

In 1930, she adopted a young baby boy, named Roger Robert, whom she gave the name Richardson. Richardson published her autobiography, Laugh a Defiance, in 1953. She died at her flat in Hastings on 7 November 1961.[1]

References

Citations

- Kean 2009.

- Atkinson 2018.

- "Hastings Press". Archived from the original on 18 February 2012.

- Gottlieb 2003, p. 165.

- "English Women's History". Archived from the original on 18 February 2012.

- "lillian dove-willcox | Woman and her Sphere". womanandhersphere.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Potterton 1977, p. 15.

- "BBC Radio 4 - Woman's Hour - Women's History Timeline: 1910 - 1919". www.bbc.co.uk.

- Gamboni 2013, p. 94.

- Craig 1969, p. 421.

- Gottlieb 2003, p. 164.

- McCouat 2016.

- McPherson & McPherson 2010.

- Boyd 2013.

Sources

- Atkinson, Diane (2018). Rise up, women! : the remarkable lives of the suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781408844045. OCLC 1016848621.

- Boyd, N (2013). From Suffragette to Fascist. The History Press.

- Craig, F.W.S., ed. (1969). British parliamentary election results 1918-1949. Glasgow: Political Reference Publications. ISBN 0-900178-01-9.

- Gamboni, D. (2013). The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. Picturing History. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-154-9.

- Gottlieb, J.V. (2003). Feminine Fascism: Women in Britain's Fascist Movement. Social and Cultural History Today. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-86064-918-9.

- Kean, Hilda (21 May 2009). "Richardson, Mary Raleigh (1882/3–1961)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56251. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McCouat, Philip (2016). "From Rokeby Venus to Fascism". Journal of Art in Society.

- McPherson, Susan; McPherson, Angela (2010). Mosley's Old Suffragette: A Biography of Norah Dacre Fox (Revised ed.). ISBN 978-1-4466-9967-6. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012.

- Potterton, H. (1977). The National Gallery: London. World of art library. Thames and Hudson.

Further reading

- Bostridge, Mark. The Fateful Year. England 1914. Viking, 2014. Chapter on 'The Slashing of the Rokeby Venus'.

- Nead, Lynda. The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality. Routledge, 1992. ISBN 0-415-02677-6

- Prater, Andreas. Venus at Her Mirror: Velázquez and the Art of Nude Painting. Prestel, 2002. ISBN 3-7913-2783-6