Morral affair

The Morral affair was the attempted regicide of Spanish King Alfonso XIII and his bride, Queen Victoria Eugenie, on their wedding day, May 31, 1906, and its subsequent effects. The attacker, Mateu Morral, acting on a desire to spur revolution, threw a bomb concealed in a floral bouquet from a Madrid hotel window as the King's procession passed, killing 24 bystanders and soldiers and wounding over 100 others, while leaving the royals unscathed. Morral sought refuge from republican journalist José Nakens but fled in the night to Torrejón de Ardoz, whose villagers reported the interloper. Two days after the attack, militiamen accosted Morral, who killed one before killing himself. Morral was likely involved in a similar attack on the king a year earlier.

The affair became a pretext to stop Francisco Ferrer, an anarchist pedagogue who ran Escuela Moderna, the influential, rationalist, antigovernment, anticlerical, antimilitary, Barcelonean school in whose library Morral worked. An unrequited love interest from the school might also have influenced Morral. Ferrer was charged with masterminding the attack, and though he was acquitted for lack of evidence, he remained a target of the government and church. The journalist Nakens and two friends, however, received prison sentences, held partially responsible for the murder Morral committed after fleeing the city. Following a prominent campaign for royal pardon, the three were released within a year of sentencing. Nakens' role in the affair spotlighted fissures in the Spanish republican movement between gradualism and near-term revolution that would later become an identity crisis.

Background

After a falling-out over politics, Mateo Morral's father gave his son a monetary parting gift, which he took to Barcelona in 1905. Morral's father was a textiles industrialist in the town of Sabadell, and Morral had traveled widely for his father's company, in addition to his prior studies abroad. He broke with his father over his support of a radicalized group of freethinkers, republicans, and freemasons—the Librepensadores. In Barcelona, Morral grew close to the anarchist pedagogue Francisco Ferrer,[1] whom he had befriended two years earlier.[2] Morral was captivated with Ferrer's Escuela Moderna,[1] a school for rationalist workers' education, and offered the project 10,000 pesetas. Ferrer, in his telling of the story, declined and instead offered Morral a job in the school's library.[3]

An unrequited love interest and a desire for infamy spurred the attempted regicide. While working at Ferrer's school, Morral became infatuated with the director of elementary studies, Soledad Villafranca, but she did not return his private admission of love. Shortly afterwards, on May 20, 1906, he told Ferrer that he would be traveling to recuperate from illness. He went to Madrid, where he walked the streets, attended tertulia roundtables, and sent postcards to Villafranca professing his undying love and his feelings of alienation. Villafranca resided with Ferrer and they were likely lovers, though it is possible that this uncertainty was just as opaque to Morral.[3]

One week before the regicide attempt, a watchman at Parque del Buen Retiro found threats against the king carved into a tree's trunk, which he later attributed to Morral.[4]

Morral used his real name to check into a pension on Calle Mayor, 88. He paid in advance and requested a room facing the street and a daily bouquet of flowers. On the day of the regicide attempt, he requested sodium bicarbonate from the pension's attendant to treat a stomach problem and requested privacy.[3]

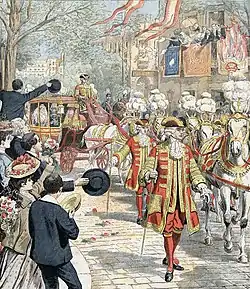

Assassination attempt

On May 31, 1906, Mateo Morral threw a bomb at King Alfonso XIII's car as he returned with Victoria Eugenie from their wedding in Madrid.[5] It was a year to the date following a similar attack on his carriage.[7] The bomb was concealed in a bouquet of flowers.[8] While the King and Queen emerged unscathed, 24 bystanders and soldiers were killed and over 100 more wounded. A British colonel observing the scene compared it to one of war. The bride's wedding gown was splattered with horse blood.[9] The King and Queen were escorted to the Royal Palace.[8]

The fugitive Morral absconded to Malasaña[10] in the ensuing chaos and sought help from the republican journalist José Nakens.[9] Nakens was a vocal opponent of anarchism, but his anticlerical leadership attracted such radicals.[1] Historians have disagreed as to whether Morral's choice of approaching Nakens was premeditated,[10] but Morral was likely introduced to Nakens through Ferrer's school, which purchased the journalist's anticlerical writings.[11] Morral introduced himself as the assassin upon entering Nakens' printing shop and recounted how Nakens had previously helped Michele Angiolillo, the Italian anarchist who had assassinated the Prime Minister of Spain in 1897. Nakens was hesitant but agreed to help. He hid Morral at the press while arranging lodging for Morral, and returned 90 minutes later to transport him to a friend's house for the night. But Morral grew distrustful during the night and was gone by morning.[10]

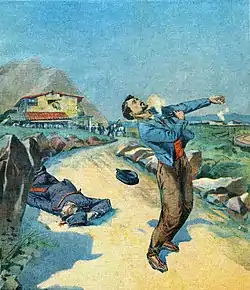

Morral was discovered at a Madrid railroad station two days after the attack, whereupon he shot a police officer and killed himself.[2] He had first arrived in Torrejón de Ardoz for food and shelter. Morral was out of place, with his Catalan accent, handsome face, and dirty clothes, by means of which the locals quickly recognized him. In lieu of a direct confrontation, they sent someone to notify Madrid of their suspicions. On the second day, village militiamen attempted to detain Morral, who countered by using his revolver to fire two fatal shots: one villager in the face and himself in the chest. Morral's body was returned to Madrid, where it was identified.[10]

Álvaro de Figueroa, 1st Count of Romanones, the Spanish Minister of the Interior, was responsible for the king's security detail.[9] Both he and the commissary of Spanish anarchist activity in France had anticipated an attack, given the high profile of the event and symbolism of Madrid as the center of the revolutionists' ire. Romanones prepared for an attack on San Jerónimo el Real—the wedding church—which Morral originally planned to attack, and then reconsidered based on the level of security. Once the royals had safely left the vicinity of the church, Romanones lay down to rest, believing that his job was done.[8] He would later offer a 25,000 peseta bounty for information in the hunt for the attacker, which went to the widow of the villager Morral had shot.[12]

Aftermath

Ferrer

Between his 1901 return from Parisian exile and the 1906 attempted regicide, the outsize influence and rapidity of the rise of anarchist pedagogue Francisco Ferrer worried Spanish authorities, who moved quickly to repress him.[13] Ferrer's school threatened many Spanish social foundations with its antimilitary, antireligious, antigovernmental curriculum and other subversive activities.[14] The conservative government and Catholic church each regarded the school as a hotbed for insurrectionary violence and heretical blasphemy, respectively. Ferrer was subject to police surveillance and harassment at home and denigrated in the press.[6]

Authorities used the 1906 regicide attempt as a pretext to stop Ferrer. He was arrested within a week of the attack and charged with both its organization and recruiting of Morral. Ferrer was imprisoned for a year while prosecutors pursued evidence for his trial.[2] The anarchist and pseudonymous writer Juan Montseny led Ferrer's legal defense. He attempted to recruit the jurist Gumersindo de Azcárate, who declined upon reviewing the preliminary evidence and concluding that Ferrer was guilty.[4]

Prosecutors had no easy case against Ferrer. In casting him as the bombing's mastermind, they relied on his ties to anarchism and revolutionary propaganda and proposed that Ferrer both fostered Morral's insurrectionism and suggested that Morral approach Nakens based on Ferrer's high regard for the journalist's works. However, in correspondence between the pedagogue and the anti-anarchist journalist just days before the bombing, the latter declined an offer from the former to write books for his school—while the two were cordial, Nakens regarded himself as an outspoken enemy of anarchism. In reply, Ferrer insisted that Nakens keep the money, perhaps intended as a bribe. The court was not convinced of conspiracy by this evidence.[11]

For his part, Ferrer proclaimed his innocence.[2] He told the investigators that he and Morral had limited interaction and that he did not know Morral was a revolutionary or even in Madrid.[3] Finding the evidence against Ferrer to be circumstantial, the court acquitted Ferrer, but not before impugning Ferrer's character and political activities: morally reprehensible but within the scope of their Constitution's freedom of expression.[15][2]

International pressure also played a major role in his release. Anarchists and rationalists likened his treatment to another Spanish Inquisition.[2] While Ferrer was jailed, the republican Alejandro Lerroux oversaw the estate and with the funds started periodicals dedicated to Ferrer and Nakens' release.[4] But while Emma Goldman proclaimed that Ferrer was known for his aversion to political violence,[2] the historian Paul Avrich has countered that Ferrer was a militant anarchist, proponent of direct action, and cognizant of the political importance of violence.[16]

Historians have disagreed on Ferrer's role in the regicide attempt. The Oxford University historian Joaquín Romero Maura concluded, based on Spanish and French police official records, that Ferrer had provided the funds and explosives as the mastermind of both bombing attempts who sought to foment a revolution. His analysis, however, took these police documents at face value when such official narratives are notorious for their fabrications from vindictive informants and conceited reporters. In this case, the police had already proven their opposition to Ferrer by twice attempting to implicate Ferrer prior to the Alfonso XIII bombings, both times unsuccessfully. And Romero Maura's same documents (and others since lost) had been insufficient at Ferrer's trial.[17] Ferrer had, however, introduced Morral to Barcelonean radicals, such as Lerroux. Some evidence suggests that Ferrer introduced Morral to a bomb expert, and that both Ferrer and Lerroux plotted a regicide to destabilize the administration and cause a revolution. Additionally, Morral had access to the school's vast collection of revolutionary propaganda.[3] "Barring the discovery of conclusive evidence," historian Paul Avrich wrote, "Ferrer's role in the Morral affair must remain an open question."[16]

Ferrer's school was a casualty of the Morral affair, closed by the government within weeks of his arrest. Multiple conservative deputies of the Spanish parliament additionally petitioned to close all secular schools but were denied.[2]

Despite Ferrer's acquittal, the police continued to believe he was guilty.[2] Ferrer continued his advocacy for rational education and syndicalist causes following his release in June 1907 but was arrested and charged in August 1909 with leading the week of protest and insurrection known as Tragic Week.[18] Though he likely participated in its events, he was not its mastermind.[19] The ensuing trial, which would culminate in his death by firing squad, is remembered as a show trial by a kangaroo court,[20] or as the historian Paul Avrich later summarized the case, "judicial murder": a successful attempt to quell an agitator whose ideas were dangerous to the status quo, as retribution for not convicting him in the Morral affair.[21]

Nakens

On the day of Morral's death, the republican journalist José Nakens had published a denunciation of the regicide attempt and terrorism writ large in his journal, El Motín, without mentioning Morral or Nakens' own harboring of the fugitive.[22] He was arrested within the week and the next day published a full accounting of his actions in two newspapers, in which he reaffirmed his opposition to anarchism, described Morral's attack as cowardly, and recanted his brief support of Morral as misguided but driven by his desire to help his fellow man.[23]

The judgment in Nakens' case came easily. While the court believed that Nakens had no prior connection with Morral, they found that his planning for Morral was more deliberate than a brief lapse of judgment. They argued that this aid led to the Torrejón villager's murder, and for this aid, sentenced Nakens to nine years of prison and financial restitution for the Royals, the military, and families affected by the bombing.[23] Nakens' friends Bernardo Mata and Isidro Ibarra were jailed as well.[24] Only half of the prison time between their June 1906 arrest and June 1907 sentencing was commuted.[24]

In Madrid's Cárcel Modelo prison, Nakens became an advocate for prison reform as a campaign mounted for his pardon. His advocacy for more humane prison conditions, through regular reports in a republican daily newspaper, improved his standing with those previously upset by his harboring of Morral.[24] Following a multifaceted campaign of letters, press, and testimony from prison officials, Nakens and his friends were pardoned in May 1908.[25]

Others

On the afternoon of the attack, both Ferrer and the republican partisan Alejandro Lerroux awaited news from Madrid while seated at separate tables in the same Barcelona café. But while Lerroux too denied involvement in and knowledge of the plot, he sat at the café having followers ready to storm the Montjuïc Castle. Lerroux's fate turned for the better with the affair. Before, he had fallen out of political favor, lost his periodical, and struggled for money. But afterwards, he was flush and the executor of Ferrer's estate.[4]

Legacy

Episodes such as the Morral affair showcased Spanish republican ability to galvanize popular support through political drama in an age of lethargy towards formal politics.[1]

It also spotlighted Spanish republican fissures that would become an identity crisis,[1] as Nakens impatiently broke from the gradualist philosophy of the old generation of republicans[26] and both republican factions showed intransigence towards cooperation.[27] The affair appeared even to favor the republican moderates (Azcárate, Nicolás Salmerón), who condemned the radical, young republicans (Lerroux, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez)[1] and made Nakens appear, by juxtaposition, to be unstable.[27] This schism appeared to hasten the coming revolution.[1]

In hindsight, historian Enrique Sanabria proposes Nakens as a tragic parable: that Nakens' decision to hide Morral reflected a willingness to work with revolutionaries that, when pronounced, would ostracize him from his more moderate republican colleagues.[27] Nakens was shortsighted to believe that his messages of egalitarianism, democracy, and cultural revolution would not appeal to the leftists he sought to avoid,[28] and his popularity within anarchist and radical circles reflected anticlericalism's status as a uniting force across the left. But whereas anticlericalism was attached to nationalism for republicans like Nakens, it was not necessarily attached for anarchists and socialists.[29] Nakens "became political roadkill" in the aftermath of the affair for his inability to draw an audience of workers while tolerating their revolutionary politics.[30]

References

- Sanabria 2009, p. 102.

- Avrich 1980, p. 28.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 103.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 106.

- Avrich 1980, pp. 27–28.

- Avrich 1980, p. 27.

- A year to the date prior, May 31, 1905, there had been a similar attempt on Alfonso XIII's life. That night, attackers threw two bombs were thrown at his carriage, which was returning from a night at the opera. Only one bomb exploded, injuring not the king but 17 bystanders and nearby vehicles.[6]

- Sanabria 2009, p. 104.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 101.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 105.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 108.

- Sanabria 2009, pp. 104–105.

- Avrich 1980, p. 26.

- Avrich 1980, pp. 26–27.

- Sanabria 2009, pp. 108–109.

- Avrich 1980, p. 29.

- Avrich 1980, pp. 28–29.

- Avrich 1980, pp. 29–31.

- Avrich 1980, p. 31.

-

- Holguin, Sandie Eleanor (2002). Creating Spaniards: Culture and National Identity in Republican Spain. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-299-17634-1. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Avrich 1980, p. 32

- Cooke, Bill (June 28, 2010). A Rebel to His Last Breath: Joseph Mccabe and Rationalism. Prometheus Books. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-61592-749-4. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Hughes, Robert (2011). Barcelona. Knopf Doubleday. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-307-76461-4. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Tusell, Javier; García Queipo de Llano, Genoveva (2002) [2001]. Alfonso XIII. El rey polémico (2ª ed.). Madrid: Taurus. pp. 185–186. ISBN 84-306-0449-9.

- Avrich 1980, p. 32.

- Sanabria 2009, pp. 106–107.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 107.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 109.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 110.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 121.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 122.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 120.

- Sanabria 2009, pp. 110, 115, 120.

- Sanabria 2009, p. 119.

Bibliography

- Avrich, Paul (1980). "The Martyrdom of Ferrer". The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 3–33. ISBN 0-691-04669-7. OCLC 489692159. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- Sanabria, Enrique A. (2009). "Republicanism, Anarchism, Anticlericalism, and the Attempted Regicide of 1906". Republicanism and Anticlerical Nationalism in Spain. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 101–122. ISBN 978-0-230-61331-7.

Further reading

- Berzal, Enrique (June 2, 2020). "1906: atentado anarquista contra Alfonso XIII". El Norte de Castilla (in Spanish). Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- Hijos de J. Espasa (1918). "Mateo Morral". Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana (in Spanish). Vol. 36. Barcelona. p. 1161. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jensen, Richard Bach (2014). "Multilateral anti-anarchist efforts after 1904". The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 295–340. ISBN 978-1-107-03405-1.

- Masjuan, Eduard (2009). Un héroe trágico del anarquismo español: Mateo Morral, 1879–1906 (in Spanish). Barcelona: Icaria. ISBN 978-84-9888-128-8. OCLC 549147889.

- "Mateu Morral i Roca". Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana (in Catalan). Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- Miguel Blanco, José (May 31, 2006). "Centenario de un atentado". 20 minutos (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- Sörenssen, Federico Ayala (March 29, 2015). "Historia de la primera gran exclusiva periodística que hubo en España". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved January 30, 2021.

External links

Media related to the Morral affair at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to the Morral affair at Wikimedia Commons