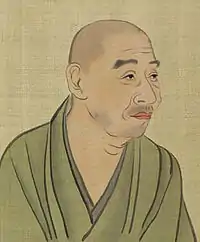

Matsumura Goshun

Matsumura Goshun[Rem 1] (jap. 松村 呉春; April 28, 1752 (traditional: Hōreki 2/3/15) – September 4, 1811 (traditional: Bunka 8/7/17)[1]), sometimes also referred to as Matsumura Gekkei (松村 月渓), was a Japanese painter of the Edo period and founder of the Shijō school of painting. He was a disciple of the painter and poet Yosa Buson (1716–1784), a master of Japanese southern school painting.

Life

Goshun was born into a wealthy family of government officials working in the royal mint (jap. kinza 金座) as the oldest of six children. His parents wished him to be well educated in the basics of Chinese and Japanese culture and had him tutored in skills such as classical history and literature, calligraphy and painting as well as writing poetry. Thus he began his education as a painter very early. In those years his masters were painters of the nanga-style, learned scholars of the literati-traditions that had come over from China, among them Yosa Buson (1716–1784) who taught Goshun among other things literati-painting and haiku-poetry.

He wasn't immediately successful as a painter but managed to support himself with the aid of Buson, who arranged him to be an advisor on literature for wealthy provincials. In 1781 his career took a turn for the worse when both his wife and his father died and his mentor Buson, himself nearing death[2] was apparently no longer able to support him. As a result of that he left his residence in the Shijō-district of Kyōto and moved to Ikeda near Ōsaka. During his time in Ikeda he continued to paint in Busons Literati-style yet was not successful enough to support himself with his painting alone.

By 1787 it was certain that he would have to join up with another band of painters, so he worked with the circle of painters around Maruyama Ōkyo (1733–1795) to work at the screen-doors of the Daijō-ji, a temple in Hyōgo prefecture. Later he would meet up with Ōkyo again, when they both sought shelter in the same temple after a fire devastated parts of Kyōto. What was apparently a good working partnership in Hyōgo now became friendship. Around 1789 Goshun returned to the Shijō-district of Kyōto, by now he had begun to incorporate elements of Ōkyos decorative and realistic art styles. He was never a formal member of Ōkyos Maruyama-school, the older friend had declined his offer to accept him as disciple stating he wanted him to remain on equal footing with his younger friend, he nonetheless became proficient in Ōkyos painting techniques. However only after Ōkyos death in 1795 did he found his own, the so-called Shijō-school (after the location of Goshuns residence and workplace) where he refined his own blend of literati-stile brushwork and decorative Maruyama-style composition and techniques.

Artistic Development

In his early career Goshun was predominantly a painter of the nanga-literati-style of painting as were most of his teacher, not the least of which Yosa Buson left a great impression on Goshun. Until around 1785 he refines this style of painting until he is proficient in Buson-style, which he seems to copy faithfully. His time in Ikeda can be viewed as a period of maturity for Goshuns Literati-style painting.

After his time with Ōkyo (after 1787) his style changed significantly. Under the influence of the Maruyama-school he began to incorporate elementes of Ōkyo and his disciples into his oeuvre and developed them.

His style can be considered mature, however, only after the death of Ōkyo in 1795 when he refined his painting style in his own school without the influence of his former masters. In this late stage of his career he seems to have all but abandoned Buson's literati-style of painting even though in Kyōto he was for a while widely considered to be his successor.

Collections

His work is held in several museums worldwide, including the Indianapolis Museum of Art,[3] the Worcester Art Museum,[4] the Brooklyn Museum,[5] the University of Michigan Museum of Art,[6] the Seattle Art Museum,[7] the Philadelphia Museum of Art,[8] the Harvard Art Museums,[9] the Ashmolean,[10] the Minneapolis Institute of Art,[11] the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,[12] the Miho Museum,[13] the Cleveland Museum of Art,[14] the British Museum,[15] the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[16] the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,[17] and the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum.[18]

Remarks

- According to standard references, his name is either Goshun, modelled after Chinese habit, or Matsumura Gekkei.

Sources

- Cleveland Museum of Art - Seventy-two Peaks Against the Blue Sky (Matsumura Goshun) Archived 2008-06-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Shiba T: Toxicity of puffer fish. Journal of Chemical Education, Oct. 1982; 59(10): 833

- "Boatman". Indianapolis Museum of Art Online Collection. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Matsumura, Goshun – People – Worcester Art Museum". worcester.emuseum.com. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Brooklyn Museum". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Exchange: Life in the Mountains". exchange.umma.umich.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Works – Matsumura Goshun – Artists – eMuseum". art.seattleartmuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Philadelphia Museum of Art - Collections Object : Warrior". www.philamuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- Harvard. "From the Harvard Art Museums' collections Seven Chinese Immortals". harvardartmuseums.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Ashmolean". collections.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Fifty Years Old, Matsumura Goshun ^ Minneapolis Institute of Art". collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Shin hana tsumi (Picking New Flowers)". collections.mfa.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Willow and White-cheeked Starling by Matsumura Goshun - MIHO MUSEUM". www.miho.or.jp. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "1986.95 | 86.95 | Ingalls Library and Museum Archives". library.clevelandart.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "calligraphy | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Matsumura Goshun | Woodcutters and Fishermen | Japan | Edo period (1615–1868)". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Blossoming Plum Tree". art.nelson-atkins.org. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- "Orchid Pavillion Gathering | Goshun (also known as Matsumura Gekkei) | Profile of Works". TOKYO FUJI ART MUSEUM. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

Literature

- Addiss, Stephen: Zenga and Nanga: Paintings By Japanese Monks and Scholars. New Orleans museum of Art. (1976)

- Cunningham, Michael R.: Byōbu: The Art of the Japanese Screen.Cleveland Museum of Art. (1984)

- Deal, William E.: Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan. Oxford University Press, US. (2007) ISBN 0-19-533126-5.

- Mason, Penelope E.: History of Japanese Art. Prentice Hall, New Jersey. (2004) ISBN 0-13-117601-3.

External links

- Bridge of dreams: the Mary Griggs Burke collection of Japanese art, a catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Matsumura Goshun (see index)