Maurice Suckling

Captain Maurice Suckling (4 May 1726 – 14 July 1778) was a British Royal Navy officer of the eighteenth century, most notable for starting the naval career of his nephew Horatio Nelson and for serving as Comptroller of the Navy from 1775 until his death. Suckling joined the Royal Navy in 1739 and saw service in the English Channel and Mediterranean Sea during the War of the Austrian Succession. With the support of relatives including Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole, Suckling was promoted quickly and received his first command in 1754. At the start of the Seven Years' War in 1756 he was promoted to captain and given a command on the Jamaica Station. There he played a major part in the Battle of Cap-Français in 1757 and fought an inconclusive skirmish against the French ship Palmier in 1758 before returning to Britain in 1760.

Maurice Suckling | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Thomas Bardwell, 1764 | |

| Born | 4 May 1726 Barsham, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 14 July 1778 (aged 52) Navy Office, London, England |

| Buried | Barsham Church |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Service/ | Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1739–1778 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations |

|

| Member of Parliament for Portsmouth | |

| In office 1776–1778 | |

Suckling was employed in the aftermath of the Capture of Belle Île in 1761 destroying French fortifications on the Île-d'Aix and went on half pay at the end of the war in 1763. He was given his next command during the Falklands Crisis of 1770, and took his nephew Nelson with him. Despite having misgivings over Nelson's suitability for the navy, Suckling supported him and saw him translated into several more active ships in order to further his naval education when Suckling himself moved to command a guard ship. Suckling left his ship in 1773 and was initially rebuffed in his attempts to gain fresh employment with the navy because of the ongoing peace, but in 1775 First Lord of the Admiralty John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, appointed him Comptroller of the Navy.

Suckling was competent in his new role and oversaw the Royal Navy's mobilisation when the American Revolutionary War began. In 1776 he was also elected Member of Parliament for Portsmouth. Suckling was able to use his powerful position to again assist Nelson, forming part of the board that passed him for promotion to lieutenant in 1777. Suckling continued throughout the period to assiduously attend meetings of the Navy Board, but was increasingly hampered by a long-term illness that caused him considerable pain. He died unexpectedly on 14 July 1778.

Early life

Maurice Suckling was born on 4 May 1726 in the rectory house in Barsham, Suffolk.[Note 1][2][3] His father was the Reverend Maurice Suckling and his mother Anne née Turner. Suckling's maternal grandfather was Sir Charles Turner, 1st Baronet, while his great-uncle was the prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole.[1][2] Suckling lived in Barsham until the age of four when his father died. His mother then moved the family, which also included his sister Catherine and brother William, to Beccles in the same county. Nothing is known of Suckling's childhood past this point apart from that he continued to live in Beccles.[2]

Suckling's immediate family, as a single parent household, was not especially rich, and he did not receive a university education. These factors limited his career prospects, with the former meaning he could not join the British Army and the latter stopping him from following his father into the clergy. Suckling did however have the support of considerable patronage from the powerful Walpole, and because of this he was able to find a place within the Royal Navy.[Note 2] At the age of thirteen, on 25 November 1739, Suckling was appointed an ordinary seaman on board the 50-gun[Note 3] fourth-rate HMS Newcastle at Sheerness Dockyard. While some records suppose that he was supported in his joining of the navy by another maternal relative, Captain George Townshend, the historian John Sugden says this was the doing of Walpole.[2][5] Suckling's first patron within the navy was Captain Thomas Fox, the commanding officer of Newcastle.[2]

Career

Early career

_BHC0371.jpg.webp)

In Newcastle Suckling saw service in the Western Approaches, the English Channel, and off Gibraltar and Lisbon. He was advanced to able seaman on 7 April 1741 before being promoted to midshipman on 7 September. In 1742 Newcastle was sent to serve in the Mediterranean Sea; while at Port Mahon in March the following year Fox was given command of the 80-gun ship of the line HMS Chichester and, continuing to support Suckling's career, he took the midshipman with him on 16 June.[3][6] While in the Mediterranean Suckling met the future Admiral of the Fleet Sir Peter Parker, at the time another junior officer, and formed a friendship that would endure throughout their respective careers.[7]

Having continued with Fox in Chichester, on 8 March 1745 Suckling took his examination for promotion to the rank of lieutenant at Port Mahon.[3][6] He was at this stage not actually eligible to take the examination, by the rules needing to be a year older and to have another seven months of sea service. Fox was one of the four captains sitting to examine Suckling, and likely because of this the deficiencies in Suckling's report were ignored and he passed.[1][6] Suckling was immediately promoted and appointed to serve as fourth lieutenant of the 70-gun ship of the line HMS Burford. While sailing off Villefranche on 7 February 1746, he was transferred to the 80-gun ship of the line HMS Russell also as fourth lieutenant.[3][6] On 9 June the following year he moved again, joining the 80-gun ship of the line HMS Boyne at the order of her flag officer, Rear-Admiral John Byng.[1][6] Having initially served again as fourth lieutenant, Suckling was promoted to become Boyne's third on 9 January 1748 and her second on 16 August.[3][6]

With the War of the Austrian Succession ending, Suckling returned home in Boyne, arriving at Spithead on 14 October. He was then, on 1 November, transferred from Boyne into the 50-gun fourth-rate HMS Gloucester as the ship's first lieutenant, which the naval historian David Syrett suggests was another appointment brought about by Suckling's patrons.[3][6] The captain of Gloucester was his relative Townshend.[5] Suckling's position in Gloucester meant that he avoided the unemployment that came to many naval officers when the Royal Navy began to decommission warships in response to the end of the war.[6]

Gloucester sailed to join the West Indies Station on 15 May 1749, and Suckling spent the next three years of his career based in the ship at Jamaica. Gloucester finally returned to England on 16 January 1753, at which time Suckling was appointed second lieutenant of the 70-gun ship of the line HMS Somerset, which was the guard ship at Chatham Dockyard. He was promoted to become Somerset's first lieutenant on 19 April before, on 2 January 1754, being discharged from the ship.[3][8] One day later he was promoted to commander.[1][8]

First commands

At the same time as his promotion Suckling was given command of the 14-gun sloop HMS Baltimore.[3] The ship was at the time serving on the North America Station, and Suckling took passage out in a merchant ship to take up his new command. He did so at Charleston, South Carolina, on 20 May. In Baltimore Suckling spent most of his time patrolling the coast of the Carolinas, with occasional diversions taking him as far north as Boston. On 11 September 1755 Suckling was with his ship at Halifax, Nova Scotia, when Vice-Admiral Edward Boscawen translated him into command of the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Lys, which had recently been captured from the French just before the start of the Seven Years' War. Lys was only armed en flute, and Suckling was ordered to sail her back to Britain.[Note 4][8]

Having left Halifax on 19 October with the rest of Boscawen's ships, Lys was separated from them in a storm but succeeded in reaching the Downs on 23 November. Suckling's command of Lys, being a ship of the line and officially the command of a post captain, combined with his patronage and the beginning of the Seven Years' War, almost guaranteed his promotion to that rank. This occurred on 2 December. Suckling had taken longer than some of his contemporaries, such as Augustus Keppel and Richard Howe, to reach the rank, but having done so he could expect to be eventually promoted to flag rank by seniority if he lived long enough.[8]

Seven Years' War

Alongside his promotion, Suckling was given command of the 60-gun ship of the line HMS Dreadnought which was the flag ship of Townshend, now a rear-admiral.[1][10] Ordered to Jamaica, Dreadnought formed part of an eleven-warship escort for a convoy that left Spithead on 31 January 1756.[10] Dreadnought arrived at Port Royal on 18 April; Townshend would go on to leave the Jamaica Station but Suckling and Dreadnought continued on.[1][10] The ship spent most of her service in harbour at Port Royal as the area was a backwater in the Seven Years' War. Suckling was able, however, to occasionally take his ship on patrols around the coast of Santo Domingo.[10]

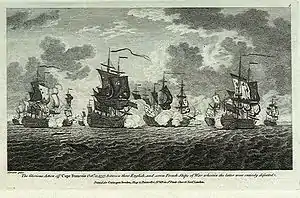

On 21 October 1757, Dreadnought and two other 60-gun ships of the line undertook an operation to intercept a French convoy leaving Cape Français. Dreadnought first spotted sails at 7am, and at midday the British found that the French squadron sent to escort the convoy had come out to engage them. It was an unexpectedly powerful squadron, consisting of seven warships, including four ships of the line. The senior British officer, Captain Arthur Forrest, met with his captains. When he suggested that the French were looking for a battle, Suckling replied "I think it would be a pity to disappoint them".[1][10][11][12] The three ships formed a line of battle with Dreadnought taking the vanguard.[1][10][13] Suckling began the battle at 3:20pm by engaging the French flag ship, the 74-gun ship of the line Intrépide. Dreadnought destroyed so many of Intrépide's spars that the French ship was unable to stop herself from falling afoul of the ship following behind her, the 50-gun fourth-rate Greenwich. This put the French squadron into confusion as their ships began to get caught up in one another. The British took advantage of this, attacking them with little return fire.[14]

The action continued for around two and a half hours.[1][10][13] At this point the French commodore, Guy François Coëtnempren de Kersaint, called for one of his frigates to tow Intrépide out of the battle.[13] The French squadron, having received heavy casualties, retreated back into Cape Français. Forrest's ships, their rigging and masts heavily damaged, were unable to chase them. This ended the Battle of Cap-Français, the only full-scale battle of Suckling's career.[1][10] The British lost twenty-four men killed and eighty-five wounded in the skirmish, of which ten and thirty respectively were from Suckling's command. Unable to re-engage the French, the ships returned to Port Royal to undergo repairs. After this Dreadnought returned to her regular duties at Jamaica.[10]

On 1 September 1758 Dreadnought was patrolling alongside the 50-gun fourth-rate HMS Assistance when they received intelligence that the French 74-gun ship of the line Palmier was off Port-au-Prince. They discovered Palmier there the following morning, and at 4am Dreadnought began to attack Palmier from close range. Assistance, however, was becalmed and unable to help Suckling in the engagement. Palmier fired into Dreadnought's rigging and, with his ship's movement disabled, Suckling was unable to stop the French ship from escaping. When Assistance finally reached Dreadnought the two ships chased after Palmier but were too far behind to re-start the engagement. Dreadnought had eight men killed and seven wounded in the action.[15][16] On 17 June 1760 Dreadnought was ordered back to England as escort to a convoy of sixty-four merchant ships. She arrived in the Downs on 29 August.[10] Suckling subsequently sailed his ship to Chatham, where she was paid off on 19 November.[3][10]

Suckling did not stay unemployed for long, being appointed to command the 70-gun ship of the line HMS Nassau on 16 January 1761.[10] Employed in the Bay of Biscay, Nassau mostly saw service implementing blockades, with there being little serious opposition for the British after the Battle of Quiberon Bay.[1][10] In June Suckling's ship reinforced the British squadron that had recently captured Belle Île, and she was then detached in a squadron under Captain Sir Thomas Stanhope. Stanhope's orders were to engage any French shipping left in the Basque Roads, and to destroy fortifications on the Île-d'Aix.[17] The squadron found no ships to attack but between 21 and 22 June Nassau and five other ships were sent on to Aix. Despite interference from French prames based in the Charente they succeeded in their task with only minor losses.[18]

Suckling left Nassau in February 1762 to recommission the 66-gun ship of the line HMS Lancaster, returning to his former ship on 22 February.[3] Suckling then stayed in Nassau until the end of the Seven Years' War, paying off his ship at the Nore in February 1763.[10] Suckling's fortune to find employment at the end of the War of the Austrian Succession did not now repeat itself, and he went ashore on half pay, probably living at his home in Woodton, Norfolk. After seven years in such a position Suckling's services were called upon again for the Falklands Crisis in 1770.[19] As the Royal Navy began mobilising in the expectation of war against Spain, he was given command of the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Raisonnable, which was fitting out at Chatham, on 17 November.[1][3][19]

Patron of Nelson

Suckling's sister Catherine had died on 26 December 1767, leaving behind three sons; William, Maurice, and Horatio Nelson.[Note 5][19][20] Suckling and his brother subsequently took an interest in promoting the careers of their nephews, and when Suckling took command of Raisonnable he brought Horatio with him, appointing him a midshipman.[19] Suckling, who had told tales of his naval exploits to Horatio while on half pay, accepted him at the direct request of Nelson's father Edmund and did not himself think that it was the right choice, saying:

What has poor Horatio done, who is so weak, that he should be sent to rough it out at sea? But let him come, and the first time we go into action a cannon ball may knock off his head and provide for him at once.[21]

Despite this attitude Suckling was happy to use his influence for Nelson's benefit;[Note 6] he wrote him into Raisonnable's books on 1 January 1771 rather than in March or April when Nelson actually joined the ship so that he could have several extra months of seniority.[Note 7][24][25] This was Nelson's first sea service although Raisonnable never left the Thames Estuary during Suckling's command, which ended with the de-escalation of tensions and the decommissioning of the ship.[1][19] On 13 May Suckling was instead given command of the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Triumph, continuing to support Nelson by taking him with him to his new ship.[3][19] Triumph was employed as a guard ship, and during Suckling's tenure she would spend time at Blackstakes, Sheerness, and Chatham. On 26 June Suckling was also appointed senior officer for his part of the Thames Estuary; he filled most of his time with paperwork regarding topics including naval discipline and the deployment of marine detachments.[19][26]

Aware that the monotony of service on board a guard ship would not provide the practical experience necessary for Nelson's naval career, Suckling organised for a Hibbert, Purrier and Horton ship captain who had served under him in Dreadnought to take Nelson to the West Indies. Nelson left on 25 July and throughout the trip was kept on the books of Triumph, which ship he re-joined on 17 July 1772.[19][27][28] Suckling continued on in Triumph throughout this, his duties at the time of Nelson's return including hosting on board First Lord of the Admiralty John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich.[29] In May 1773 Suckling had Nelson transferred to serve in the 8-gun bomb vessel HMS Carcass for an expedition to the North Pole, he having previously operated with Carcass' commander Captain Skeffington Lutwidge.[25][30][31] Nelson having returned from this, Suckling then had him join the 24-gun frigate HMS Seahorse on 27 October. Seahorse was commanded by another friend and old Dreadnought shipmate, Captain George Farmer.[32] Suckling left Triumph on 1 December when his standard three-year appointment came to an end.[3][33]

Comptroller of the Navy

Suckling returned to half pay; he was still in his prime, a handsome and slim man despite some gout in his right hand and a thinning hairline.[19][24] As a senior captain there were limited positions available for him within the navy while the country was at peace.[19] Suckling showed an interest in working ashore when positions in Newfoundland and Jamaica arose in 1775.[34] Employment was also available for naval officers within the civil side of the navy's command, the Navy Board; having spent two years unemployed, on 12 April Suckling was appointed Comptroller of the Navy.[1][35]

The Comptroller of the Navy was the head of the Navy Board, responsible for all Royal Navy warship construction and upkeep as well as troop transports and dockyards. The position was highly prestigious as well as important and why Suckling, a relatively unknown candidate, was chosen by Sandwich is not known.[36][37] The naval experience that Suckling brought to the position was of great value to Sandwich, who went about reforming naval administration with particular emphasis on making Royal Navy shipyards more productive.[1][38]

Suckling proved adept as head of the Navy Board, initially in peace and then during the American Revolutionary War.[1][36] Despite his deep commitment to public duty he found it time-consuming and arduous work.[36][39] During his tenure the mobilisation of the navy for war saw the number of ships under his purview expand from 110 in October 1775 to 306 in July 1778. Suckling attended the majority of meetings called by the Navy Board, often six days a week, overseeing both the growth of the navy and the creation of a fleet of 416 troop transports to convey the army across to America.[36] His hard work was done in tandem with that of Rear-Admiral Sir Hugh Palliser, his predecessor as Comptroller of the Navy and the incumbent First Naval Lord.[1]

Suckling continued to receive personal advancement during this period, being elected unopposed as member of parliament for the Admiralty-controlled constituency of Portsmouth on 18 May 1776; he never voted or made a speech during his tenure in the House of Commons.[36][40] Suckling was also able to use his position to again assist his nephews, appointing Maurice a clerk in the Navy Office in November 1775 and on 9 April 1777 serving as an examining captain on Horatio's lieutenancy examination. Nelson was, as Suckling had been, underage for the position but this was ignored and he passed, being appointed to serve in the 32-gun frigate HMS Lowestoffe.[36][41]

A view promoted in older biographies of Nelson,[Note 8] that he was unaware his uncle was to examine him and that Suckling did not tell the other examiners of their relationship, "not wish[ing] the younker to be favoured", has been questioned in more recent years by Sugden and the naval historian R. J. B. Knight.[43][44] Nelson was promoted to captain two years later, beating the average time of a lieutenant to reach captaincy by eight years.[45]

Death and legacy

While continuing in work, from around January 1777 a long-term but undiagnosed illness had begun to take a considerable toll on Suckling's health.[1][34] He would often spend days at a time "in much bodily pain", as he wrote to Sandwich on 28 January.[34][46] The naval historian N. A. M. Rodger argues that Suckling was a "less successful choice" than Palliser had been because of this, but that he was still an able man.[38] Having attended his last meeting of the Navy Board on 4 March 1778, he suddenly and unexpectedly died in his apartments at the Navy Office, London, on 14 July, aged fifty-two.[1][47][48] He was buried in the chancel of Barsham Church.[1]

Having missed almost every battle that took place during the War of the Austrian Succession and Seven Years' War, Syrett argues that the majority of Suckling's career was "uneventful and perhaps even lacklustre".[47] While he found success as Comptroller of the Navy that, Syrett suggests, might have seen him become "one of the great naval administrators of the Royal Navy", the overwhelming reason for Suckling's enduring fame lies with Horatio Nelson. Suckling is most remembered as the man who was instrumental in beginning and supporting Nelson's naval career as he grew to become a national hero.[49] Even after Suckling's death his relationships with officers such as Parker resulted in preferment for Nelson.[7] Nelson would go on to remember his uncle's conduct at Cape Français, recollecting it prior to fighting the Battle of Trafalgar exactly forty-eight years later.[1] Sugden emphasises Suckling's importance to Nelson, saying that he had "managed his career, planned every move and cleared away every obstacle".[50] Nelson said after Suckling's death that:

I feel myself to my country his heir...And it shall, I am bold to say, never lack the want of his counsel. I feel he gave it to me as a legacy, and had I been near him when he was removed, he would have said, "My boy, I leave you to my country. Serve her well, and she'll never desert, but will ultimately reward you."[22]

Personal life

Suckling married his cousin Mary Walpole, daughter of Horatio Walpole, 1st Baron Walpole, on 20 June 1764.[1][40] The marriage further increased Suckling's network of powerful connections, as Mary was the sister-in-law of the daughter of William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire, another powerful figure.[5] The couple did not have any children before Mary died in 1766.[1][40] The death of much of Suckling's family before him left "a worrying void in his life" according to Sugden. With very few close relatives, his will of 1774 left bequests to his brother and some of the Walpole family, but the majority of his wealth was split between Catherine's children.[25] Suckling left his sword, said to have previously been owned by Galfridus Walpole, to Nelson.[22]

Notes and citations

Notes

- Dates are in New Style. Ruddock Mackay in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography instead dates Suckling's birth to 1725.[1]

- In a similar fashion Suckling's brother William would go on to have a career in the Civil Service.[2]

- The number of guns refers to the number of long guns a ship was established to carry on its decks.[4]

- The naval historian Rif Winfield records Suckling taking command of Lys in June rather than September.[9]

- Syrett instead records Catherine's date of death as 26 June.[19]

- Alongside his wider support of Nelson's career Suckling would also provide him with a series of detailed instructions for managing and commanding a ship, ranging from keeping the magazine secure to how to stow hammocks.[22]

- At the time of his official joining date Nelson was in fact still at school in Norfolk.[23]

- Older biographers who recorded this view include James Stanier Clarke & John McArthur, Nicholas Harris Nicolas, David Howarth, and Christopher Hibbert[42]

Citations

- Mackay (2008).

- Syrett (2002), p. 33.

- Harrison (2019), p. 464.

- Winfield (2008), pp. 10–11.

- Sugden (2005), p. 55.

- Syrett (2002), p. 34.

- Sugden (2005), p. 128.

- Syrett (2002), p. 35.

- Winfield (2007), p. 259.

- Syrett (2002), p. 36.

- Allen (1852), p. 178.

- Clarke & McArthur (2010), p. 270.

- Clowes (1898), p. 165.

- Allen (1852), pp. 177–178.

- Clowes (1898), p. 300.

- Beatson (1804), p. 125.

- Clowes (1898), p. 236.

- Clowes (1898), pp. 236–237.

- Syrett (2002), p. 37.

- Sugden (2005), p. 40.

- Sugden (2005), p. 39.

- Sugden (2005), p. 132.

- Croft (2023), p. 43.

- Sugden (2005), p. 54.

- Sugden (2005), p. 56.

- Sugden (2005), pp. 54–55.

- Sugden (2005), pp. 56–57.

- Tracy (2006), p. 263.

- Sugden (2005), p. 57.

- Sugden (2005), p. 62.

- Sugden (2005), p. 64.

- Sugden (2005), pp. 82–83.

- Clarke & McArthur (2010), p. 277.

- Sugden (2005), p. 105.

- Syrett (2002), pp. 37–38.

- Syrett (2002), p. 38.

- Sugden (2005), pp. 105–106.

- Rodger (2004), p. 372.

- Sugden (2012), p. 6.

- Drummond, Mary M. "Suckling, Maurice (1726–78)". History of Parliament. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- Sugden (2005), p. 106.

- Croft (2023), pp. 39–40.

- Croft (2023), p. 38.

- Croft (2023), p. 40.

- Croft (2023), pp. 44–45.

- Talbott (1998), p. 25.

- Syrett (2002), p. 39.

- "London". London St James Chronicle. London. 16 July 1778. p. 3.

- Syrett (2002), pp. 1, 39.

- Sugden (2005), p. 131.

References

- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy. Vol. 1. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 557527139.

- Beatson, Robert (1804). Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain from 1727 to 1783. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme. OCLC 557578326.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (2010) [1805]. The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 14. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10801-853-1.

- Clowes, William Laird (1898). The Royal Navy, a History from the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 3. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 645627800.

- Croft, Harrison (February 2023). "'I Did Not Wish the Younker to be Favoured': Reconsidering Nelson's examination for lieutenant". The Mariner's Mirror. 109 (1): 38–49. doi:10.1080/00253359.2023.2156213. S2CID 256417566.

- Harrison, Cy (2019). Royal Navy Officers of the Seven Years War. Warwick, England: Helion. ISBN 978-1-912866-68-7.

- Mackay, Ruddock (2008). "Suckling, Maurice". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Rodger, N. A. M. (2004). The Command of the Ocean. London: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-713-99411-8.

- Sugden, John (2005). Nelson: A Dream of Glory. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-712667-43-2.

- Sugden, John (2012). Nelson: The Sword of Albion. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-224060-98-1.

- Syrett, David (February 2002). "Nelson's Uncle: Captain Maurice Suckling". The Mariner's Mirror. 88 (1): 33–40. doi:10.1080/00253359.2002.10656826. S2CID 161883184.

- Talbott, John E. (1998). The Pen & Ink Sailor: Charles Middleton and the King's Navy, 1778–1813. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-4452-8.

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's Who in Nelson's Navy. London: Chatham. ISBN 978-1-86176-244-3.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-78346-925-3.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1814. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84415-717-4.