Mausoleum of Lanuéjols

The mausoleum of Lanuéjols is a Gallo-Roman funerary monument located in the commune of Lanuéjols, in the French department of Lozère (Occitania region).

| Mausoleum of Lanuéjols | |

|---|---|

| Native name French: Mausolée des Pomponii, Lou Mazelet | |

The Roman mausoleum at Lanuéjols. | |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 44°30′00″N 3°34′17″E |

| Built | Second half of the second century |

| Architectural style(s) | Roman mausoleum, made of Limestone |

| Designated | 1840 |

| Region | Occitania |

| Department | Lozère |

| Commune | Lanuéjols |

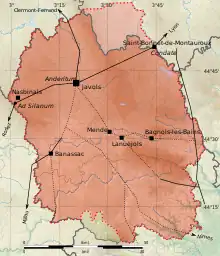

Location of Mausoleum of Lanuéjols in Occitanie  Mausoleum of Lanuéjols (France) | |

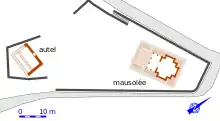

It was built on the model of a mausoleum-temple in the second half of the 2nd century AD by a wealthy family who certainly lived nearby. Dedicated to the memory of two of the family's sons, it is also known as the "Mausolée des Pomponii", after the wealthy family, and in Occitan as "Lou Mazelet". Although this is the best-known monument in Lanuéjols, it is part of a funerary complex that also includes an altar, in front of which funerary or commemorative ceremonies were probably held, and a third, non-visible building, probably even larger than the Pomponii mausoleum, which may have been the parents' tomb.

The mausoleum's particular topographical location has led to its partial burial on several occasions under the sediment left by a stream in the surrounding terrain, necessitating several excavations. The mausoleum, listed as a protected historic monument in 1840, was the subject of several excavation campaigns in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Geographical and historical context

In modern times, Lanuéjols, a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Mende, appears to have been a small secondary settlement[1][T 1] in the center of the civitas des Gabali.[2] However, it is not yet clear whether this was a secondary settlement, probably small in size but grouping together several settlements, or a villa belonging to a single estate.[3] Lanuéjols may have been crossed by an ancient road running from Javols to Bagnols-les-Bains via the Mende site,[T 2] an area rich in galena deposits that were exploited from this period onwards.[T 3] In addition to the funerary complex and its mausoleum, the ancient remains identified at Lanuéjols include a necropolis used from the High Roman Empire to the Early Middle Ages, several remains of unidentified buildings and a large number of finds (architectural elements, some of which were used in more recent buildings in the area, coins, ceramic shards) scattered over several sites.[4][T 3]

The ancient site of Pré de Clastres, on the banks of the Gravière stream, lies at the bottom of the Valdonnez valley, between the Causse de Mende to the north and Mont Lozère to the southeast.[5] The mausoleum's orientation, from northeast to southwest, respects that of the valley in which it is built. The presence of the creek's alluvial fan and the location of the burial site, five meters below the surrounding land, explain why the mausoleum is periodically invaded by sediment, sometimes to a height of several meters;[6] paradoxically, this layout probably protected it from atmospheric aggression and looting.[7][8]

The large mausoleum at Lanuéjols is sometimes referred to locally as "Lou Mazelet", which in Occitan means a small house or farmhouse (mas).[9][10]

Studies, excavations and restoration

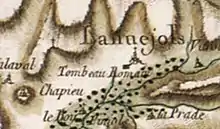

The mausoleum of Lanuéjols is mentioned in a notarial act dating from 1254, which is accompanied by a very brief description of the building,[T 4] whose construction is attributed to the "Saracens" (a term to be interpreted in the broad sense of pagans).[11] In the 18th century, it was recognized by the ecclesiastic L'Ouvreleul as a "Roman tomb" supposedly belonging to Lucius Munatius Plancus,[12][N 1] and it is under this name that it appears on sheet 55 of the Cassini map.[13] An initial transcription of the inscription engraved on the door lintel was made in 1784; it demonstrated the funerary nature of the monument, but invalidated its attribution to Plancus.[T 4]

In 1805, faced with the risk of the mausoleum being dismantled by the owner of the land, who had acquired it as national property and wished to recover the stones, the State intervened to buy the plot and the building. In 1813, the funerary complex was cleared of the three-meter-thick sediments that covered it,[15] and in 1840, the monument known as the "Roman tomb" was included on the first list of protected French historic monuments.[16] Left untouched, the mausoleum was again buried under alluvial deposits until 1855, when excavations began.[17] A plan drawn up in 1860 mentions another building, but this work was poorly documented and the remains were soon buried under the alluvium. In 1881, the foundations of a third monument, probably an altar, were uncovered a few dozen meters southwest of the Pomponii mausoleum.[T 5]

Once again, excavation work had to be carried out before and after World War I. Excavations in the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated the absence of a funerary crypt in the two accessible monuments, and enabled us to refine the chronology of the complex's construction.[T 4] From 1992 onwards, the project to develop the site as a tourist attraction led to new preventive archaeology studies. An exhaustive survey of the 150 stone blocks[18] scattered across the site and resulting from the dismantling of its structures demonstrated the existence of the monument glimpsed in the mid-19th century, and enabled it to be located. These blocks were aligned on either side of an alleyway, as it was impossible to attribute them to a specific building, with the exception of a few which came with certainty from the mausoleum or the altar, and were replaced on these monuments.[T 6] In addition to the restoration of the site's monuments, the enhancement work carried out from 1991 onwards consisted of superficial earthworks, the installation of a drainage network and footpaths, and the creation of illustrated explanatory panels near the mausoleum.[19] As for the monument itself, the staircase leading to the pronaos was rebuilt in 1999 and 2000.[20]

To ensure the safety of visitors and the preservation of the monument, the mausoleum's entrance door and its engraved lintel were shored up in 2013.[21]

Funerary complex

While the Pomponii mausoleum is the main feature of the site, and the most famous for being the best preserved and oldest documented, two other buildings are known: a ceremonial altar, the base of which is still visible to the west of the mausoleum, and a second tomb, the remains of which were quickly uncovered in the mid-19th century before any in-depth study could be carried out, and which lies to the south of the altar.[T 7]

The presence of "neighbouring buildings" (in the plural, but without further precision) is mentioned in the temple's dedication.[22]

In addition, the discovery of a pit containing meal reliefs not far from the Pomponii mausoleum shows that funeral banquets in honor of the deceased were held on the site.[23]

Components

Mausoleum of the Pomponii

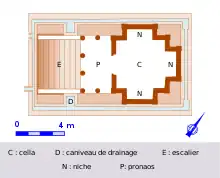

Built in large units of Jurassic dolomitic limestone,[24] probably quarried locally,[25] this mausoleum is typical of the "mausoleum-temple" architectural model that spread throughout the provinces of the Roman Empire from the end of the 1st century, with the exception of Roman Gaul, where it remained rare.[T 8] Its morphology is reminiscent of traditional Latin temples, with cella and pronaos. The older Ummidia Quadratilla mausoleum at the Italian archaeological site of Cassino is comparable, at least for the cruciform plan of the cella.[26] The Fabara mausoleum in the Spanish province of Zaragoza, which is more or less contemporary with the Lanuéjols mausoleum, is based on a similar architectural design.[23]

Traces of the construction site (lifting gear supports, drainage ditches, stone-cutting waste) have been identified in the vicinity of the Lanuéjols monument.[23]

Cella

The cella was built on an almost square plan (interior dimensions 5.40 × 5.20 m), but features three outward-projecting niches 1.30 m deep on the northwest, northeast and southeast sides.[27] The niches are finished off externally with a triangular pediment supporting a gable roof; the axial niche on the northeast side, moreover, is vaulted internally in a low barrel vault with a decorated archivolt.[T 6] The height of the cella is known right down to the base of the roof: the cornices of the central chamber rise 4.50 m above the podium, while those of the niches are approximately 2.20 m high.[28] Tuscan-order corner pilasters adorn each corner of the cella and its niches.[T 6] The walls, approximately 0.60 m thick,[25] are made of large blocks assembled with live joints and secured with metal studs, most of which have now disappeared.[29] Some of these blocks were cut at right angles to the corners of the monument.[30] It is possible that the walls were faced with marble.[22]

The floor of the cella is paved with large slabs,[27] but these are laid directly on the backfilled podium floor and do not cover a crypt that may have housed the tombs. We must therefore assume that the bodies of the deceased were preserved in sarcophagi, or urns if they were cremated, perhaps arranged in the cella's side niches, which were large enough to accommodate them. The axial niche opposite the door, smaller than the other two, may have housed statues of the Pomponii family.[T 8]

The door to the southwest, 2.08 m wide and 2.55 m high, is topped by an ornamented semi-circular tympanum above the lintel. The tympanum features a rabbet designed to accommodate a sash, perhaps glazed, that would provide light to the cella.[T 8] The archivolt of this spandrel is decorated with engraved genii, leaves and bunches of grapes.[16]

Pronaos and podium

Originally, the façade of the pronaos was adorned with four Corinthian columns; two other columns were arranged on the returns to the cella, one on each side; fragments of these columns have been found on the site and in a nearby farmhouse.[19] The façade columns originally supported an entablature composed of an architrave, a frieze and a cornice decorated with modillions. A triangular pediment crowned the whole.[T 6]

The monument is built on a podium preceded by an eight-step staircase, bordered by two echiffre walls aligned with the corners of the cella.[31] The podium is surrounded by a drainage channel cut into the thickness of the slabs that make up the podium, with drainage on the façade side.[T 6] The staircase and pronaos were restored in 1999,[20] using scattered blocks recognized as belonging to them, complemented by modern blocks of the same workmanship, but identified to differentiate them.[32]

Engraved lintel

The lintel above the cella's entrance door measures 2.20 × 0.60 × 0.60 m. Wider than the cella door and supported laterally by winged genii, it is engraved on the outside with a five-line inscription in the form of an epitaph:

- HONOR[I] ET MEMOR[I]AE LVCI(I) POMPON(II) BASSVL(I) ET L(VCII) POMP(ONII)

- BALBIN(I) FILIORVM PI(I)SS[I]MORVM LVCIVS IVL[I]VS BASSIANVS PATER

- ET POMPONIA REGOLA MATER AEDEM A FVNDAMENTO VS-

- QUE CONSVMMAT[I]ONEM EXSTRVXERVNT ET DEDICAVERVNT

- CVM AEDIFICIIS CIRCVMIACENTIBVS[33]

"In honor and memory of Lucius Pomponius Bassulus and Lucius Pomponius Balbinus, most respectful sons, Lucius Iulius Bassianus, their father, and Pomponia Regola, their mother, built this monument, as well as the surrounding buildings, from foundation to completion and dedicated it (to their children)."[T 9]

This epitaph gives the monument its nickname, the mausoleum of the Pomponii. It bears witness to a practice, more common in the upper classes of society, of naming children after their mother (in this case Pomponius) rather than their father.[34]

.jpg.webp) Mausoleum partially buried and flooded (drawing from 1834).

Mausoleum partially buried and flooded (drawing from 1834)._1.JPG.webp) Overview

Overview_2.JPG.webp) Detail of the archivolt, inside the cella arch.

Detail of the archivolt, inside the cella arch. Detail of the archivolt, inside the cella arch. Decor with dove and fruit bowl

Detail of the archivolt, inside the cella arch. Decor with dove and fruit bowl_3.JPG.webp) Detail of façade, southeast exterior.

Detail of façade, southeast exterior._4.JPG.webp) Podium and steps.

Podium and steps. Corner element of the mausoleum cornice (head down).

Corner element of the mausoleum cornice (head down).

Ceremonial altar

| External image | |

|---|---|

A structure levelled at the first course of its elevation was discovered in 1881, 35 m south-west of the main monument and more than a metre below it; it was cleared in the 1970s and excavated until the 1990s. Measuring 10.50 x 8 m, it was built in the same large-scale limestone as the mausoleum, with a paved floor.[35] It probably comprised a front portico with columns, preceded by a courtyard. Numerous blocks scattered around the site can be attributed to this building; it is certain that the excavations revealed its entire footprint and demonstrated the absence of a funerary crypt.[36]

The hypothesis of an altar used to celebrate ceremonies in memory of the deceased has been put forward.[T 5]

Second tomb

To the south of the assumed altar, another monument was unearthed in 1856, without any precise description being given, and was almost immediately resurfaced by alluvial deposits; only a topographical plan from 1860 mentions it. Its location some thirty meters south of the altar was confirmed by excavations in the 1990s.[37] Two blocks, falsely attributed to the altar and featuring garland-based decoration, and a third found on site are the only ones that can be said to belong to it with any certainty; another block reported in 1944 in the Lanuéjols cemetery has the same characteristics.[T 5]

The size of the blocks that make up this other monument, which does not match that of the elements already known from the site, suggests that it was even more imposing than the Pomponii mausoleum. It could be the tomb of the parents, Lucius Julius Bassianus and Pomponia Regola.[T 5]

Sponsors: a wealthy family

Lucius Julius Bassianus, the father of the family, was a notable man, certainly a Roman citizen since he adopted the three-part name. He probably lived nearby, but his villa has not been located.[T 10] He was undoubtedly a wealthy landowner who could afford to erect this monumental mausoleum in memory of his two prematurely deceased sons. It is also possible that part of his fortune came from silver-lead mining near Lanuéjols.[T 11]

The style of the mausoleum, sometimes compared to funerary or religious monuments in Roman Syria, and the name "Bassianus" also borne by the Syrian-born emperor Elagabalus, may have led to the attribution of Syrian origins to the Lanuéjols family,[38] although there is no tangible proof of this.[39]

Chronology

As knowledge of the mausoleum progressed, so did the dating hypotheses. In 1908, Émile Espérandieu dated the monument to the 1st century AD.[40] In 1941, Fernand Benoit used comparisons between the Lanuéjols mausoleum and other monuments in the same style to determine that the mausoleum was "from a period later than Diocletian" and, in any case, "closer to Syrian buildings of the fourth and fifth centuries than those of the Empire".[41] Entries in the Mérimée database suggest construction in the 2nd[20] or 3rd century.[38] Excavations carried out in the 1990's have yielded material that points to construction in the second half of the 2nd century, or even in the third third of that century.[T 9] The entire burial site seems to have ceased to be frequented towards the end of the 3rd or beginning of the 4th century,[T 5] and the mausoleum was occasionally used as a temporary shelter by passing travellers.[23]

However, the discovery of a necropolis consisting of some fifty Late Antique burials explored in the 19th century and again in 1997, to the northeast of the mausoleum, seems to indicate a form of persistence in the site's funerary vocation.[42][43][44] The creation of a rough stone floor around the monuments, whose primary function seems to have been to combat persistent dampness, can be traced back to this period.[45]

Notes

References

- Carte archéologique de la Gaule - La Lozère. 48, Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, 2012 :

- Trintignac (2012), p. 76

- Trintignac (2012), p. 74

- Trintignac (2012), p. 294

- Trintignac (2012), p. 296

- Trintignac (2012), p. 300

- Trintignac (2012), p. 297

- Trintignac (2012), pp. 295–296

- Trintignac (2012), p. 298

- Trintignac (2012), p. 299

- Trintignac (2012), p. 295

- Trintignac (2012), p. 301

- Other references

- Trintignac 2012, p. 76.

- Baret, Florian (2015). Les agglomérations « secondaires » dans le Massif Central (cités des arvernes, vellaves, gabales, rutènes, cadurques et lémovices) : Ière - 5ème siècle: thèse pour obtenir le grade de docteur d'université en archéologie (in French). Vol. 1. Clermont Université. p. 115 et 272..

- Baret, Florian (2022). Origines de la ville dans le Massif Central. Les agglomérations antiques: Catalogue critique des sites. Villes et Territoires (in French). Tours: Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais. p. Lanuéjols. ISBN 978-2-86906-804-9..

- Fabrié 1989, p. 89.

- Joulia 1975, p. 275.

- Roussel 1859, p. 28.

- "Définition de l'aléa inondations sur la commune de Lanuéjols (48)" (pdf). lozere.gouv.fr (in French). p. 10. Retrieved 23 May 2020..

- Benoit 1941, p. 119.

- Blanchet, Adrien (1902). "Monuments de la Lozère". Bulletin Monumental. LXVI: 260..

- Boucoiran, Louis (1875). Dictionnaire analogique & étymologique des idiomes méridionaux qui sont parlés depuis Nice jusqu'à Bayonne et depuis les Pyrénées jusqu'au centre de la France (in French). Nîmes: Baldy-Riffard. p. 907..

- Germer-Durand, François (1881). "Note sur le monument de Lanuéjols". Bulletin de la Société d'agriculture, industrie, sciences et arts du département de la Lozère (in French). XXXII: 177..

- Ignon, Jean-Joseph-Marie (1841). "Les monumens antiques et du Moyen-Âge du département de la Lozère". Mémoires et analyse des travaux de la Société d'agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts de la ville de Mende, chef-lieu du département de la Lozère (in French): 138..

- L'Ouvreleul, Jean-Baptiste (1724). Mémoire historique sur le pays de Gévaudan et la ville de Mende (in French). Mende. p. 112..

- Trintignac 2012, p. 74.

- Balmelle 1937, p. 25.

- Base Mérimée: PA00103833, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French) and Base Mérimée: IA48000382, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French).

- Roussel 1859, p. 29.

- Joulia, Paillet & Thouin 2000, p. 147.

- Joulia, Paillet & Thouin 2000, p. 150.

- Base Mérimée: IA48000382, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French).

- Gintrand, Patrice; Pauget, Raymond. "Les cahiers du pétrimoine lozérien. No. 10, septembre 2013" (pdf). lozere.gouv.fr (in French). p. 44. Retrieved May 24, 2020..

- Roussel 1859, p. 32.

- Conche, Frédéric (1995). "Lanuéjols - Pré de Clastres : les mausolées romains". Bilan scientifique 1994 (pdf) (in French). SRA/DRAC Languedoc-Roussillon. p. 149..

- "139B2 – Calcaires jurassiques du Causse Noir" (pdf). rhone-mediterranee.eaufrance.fr (in French). Retrieved November 22, 2022..

- Balmelle 1937, p. 27.

- Joulia 1975, p. 278.

- Benoit 1941, p. 120.

- Joulia 1975, p. 281.

- Benoit 1941, p. 122.

- Benoit 1941, p. 123.

- Joulia, Paillet & Thouin 2000, p. 148.

- Joulia, Paillet & Thouin 2000, p. 149-150.

- CIL XIII, 1567.

- Rémy, Bernard; Thauré, Marianne (2019). Gabales. Inscriptions latines d'Aquitaine (in French). Ausonius. p. notice No. 23. ISBN 978-2-35613-322-9..

- Napoli, Joëlle (1993). "Lanuéjols - Le mausolée romain". Bilan scientifique 1992 (pdf) (in French). SRA/DRAC Languedoc-Roussillon. pp. 93–94..

- Joulia, Paillet & Thouin 2000, p. 145.

- Paillet, Jean-Louis (1995). "Lanuéjols - Pré de Clastres : le monument funéraire". Bilan scientifique 1994 (pdf) (in French). SRA/DRAC Languedoc-Roussillon. p. 150..

- Base Mérimée: PA00103833, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Camus, Renaud (2010). Le département de la Lozère (in French). Pol éditeur. p. 57. ISBN 978-2-84682-977-9..

- Espérandieu, Émile (1908). Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine (in French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. p. 472..

- Benoit 1941, p. 125 et 130.

- Bosse, Louis (1864). "Un cimetière ancien à Lanuéjols". Bulletin de la Société d'agriculture, industrie, sciences et arts de la Lozère (in French) (12): 153–163..

- Joulia, Paillet & Thouin 2000, p. 146-147.

- Llopis, Éric (1998). "Lanuéjols - RD 41". Bilan scientifique 1997 (in French). SRA/DRAC Languedoc-Roussillon. p. 115..

- Piskorz, Michel (1994). "Lanuéjols - Les mausolées romains". Bilan scientifique 1993 (in French). SRA/DRAC Languedoc-Roussillon. pp. 125–126..

Bibliography

Documents used as a source for this article.

Specific literature on the Lanuéjols funeral complex

- Benoit, Fernand (1941). "Un monument « préchrétien » du Bas-Empire : le mausolée de Lanuéjols (Lozère)". Bulletin Monumental (in French). C (1–2): 119–132. doi:10.3406/bulmo.1941.8555.

- Joulia, Jean-Claude (1975). "Ensemble monumental de Lanuéjols (Lozère)". Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise (in French). VIII: 275–294. doi:10.3406/ran.1975.982.

- Joulia, Jean-Claude; Paillet, Jean-Louis; Thouin, Stéphane (2000). "Le mausolée romain de Lanuéjols : fouille, restauration et mise en valeur". Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise (in French) (1): 144–150.

- Roussel, Théophile (1859). "Notes sur le monument romain de Lanuéjols". Bulletin de la Société d'agriculture, industrie, sciences et arts du département de la Lozère (in French). X: 27–44.

Publications on the heritage of Lozère or funeral rites

- Balmelle, Marius (1937). Répertoire archéologique du département de la Lozère: période gallo-romaine (in French). Montpellier: Manufacture de la Charité.

- Blaizot, Frédérique (2009). Pratiques et espaces funéraires dans le centre et le sud-est de la Gaule durant l'antiquité: Gallia (in French). CNRS..

- Fabrié, Dominique (1989). Carte archéologique de la Gaule: La Lozère. 48 (in French). Paris: Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. p. 71-72. ISBN 2-87754-007-3.

- Hatt, Jean-Jacques (1986). La tombe gallo-romaine (in French). Paris: éditions Picard. ISBN 978-2-7084-0323-9..

- Moretti, Jean-Charles; Tardy, Dominique (2002). "Inventaire des monuments funéraires de la France gallo-romaine". In Musée archéologique Henri-Prades (ed.). La mort des notables en Gaule romaine. pp. 27–102. ISBN 978-2-9516-6790-7.

- Wolfgang Spickermann (2001). Religion in den germanischen Provinzen Roms (in German). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-147613-6.

- Trintignac, Alain (2012). Carte archéologique de la Gaule: La Lozère. 48 (in French). Paris: Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, Maison des Sciences de l'Homme. p. 294-302. ISBN 978-2-87754-277-7.