Max Ringelmann

Maximilien Ringelmann (10 December 1861, Paris – 2 May 1931, Paris)[1]: 55 was a French professor of agricultural engineering and agronomic engineer who was involved in the scientific testing and development of agricultural machinery.[1]

Maximilien Ringelmann | |

|---|---|

| Born | December 10, 1861 |

| Died | May 2, 1931 (aged 69) |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | National Institute of Agronomy |

| Known for | Ringelmann effect, Ringelmann scale |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | École Nationale d’Agriculture |

Ringelmann's interests were wide-ranging: he developed the Ringelmann scale which is still used to measure smoke. He also discovered the Ringelmann effect in social psychology, viz, that when working in groups, individuals slacken.

Education

After graduating from the public schools of Paris, Ringelmann studied at the Institute National Agronomique (National Institute of Agronomy), where he was an outstanding student. He also attended Hervé Mangon’s evening course in rural engineering at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers (National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts). (Charles-François Hervé Mangon (1821–1888) had been trained as a civil engineer, but his interest shifted to agriculture, where he studied irrigation, drainage, fertilizers, etc.)[2] Ringelmann also attended courses at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées (National School of Bridges and Roads), a civil engineering school.[1]: 47

Career

Starting in 1881, Ringelmann tutored the course in rural engineering at the École Nationale d’Agriculture (National School of Agriculture) in Grand Jouan, Nozay, France.[3] By 1883, he was contributing a weekly column to the Journal d’Agriculture Pratique (Journal of Practical Agriculture).[1]: 51

Up to that time, the development of agricultural machinery had been done largely by amateurs. Eugène Tisserand, a director at the Ministry of Agriculture, wanted to apply a scientific approach to the development and evaluation of farm machinery. He therefore requested that Ringelmann draft plans for a facility for testing agricultural machinery, which after many vicissitudes opened in 1888. The facility was established on Jenner Street in Paris and Ringelmann was named its director.[1]: 48

He adapted industrial instruments where possible, but he also designed and had built instruments such as traction dynamometers, rotational dynamometers, profilographs, etc. He aimed to determine the efficiency of agricultural machinery, its economics, the quality of the work performed, etc. His wide-ranging interests soon led him to extend his research to include all branches of rural engineering: construction, drainage, irrigation, electrification, hydraulics.[1][4]

In 1887, Ringelmann was elected to the Académie d'Agriculture, and in the same year, he became professor of mechanics and rural engineering at the École Nationale d’Agriculture in Grignon. In 1897, he succeeded his former professor Hervé Mangon as professor of rural engineering at the Institute National Agronomique. He became in 1902 professor of colonial rural engineering at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Agriculture Coloniale in Nogent-sur-Marne.[1]: 55

Ringelmann traveled within Europe and to North America in order to observe those areas where mechanization of agriculture had progressed rapidly. He also traveled to France's colonies—particularly in North Africa—in order to study the special problems posed by the local climate and by the pre-industrial technology that was used by the native farmers. His expertise in agricultural engineering was sought by inventors, industrialists and farmers.[1]: 49

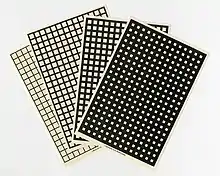

Ringelmann smoke charts

In 1888 Ringelmann proposed a specification for a simple set of grids for measuring the density of smoke. This became known as the Ringelmann scale.[5][1] By 1897, printed cards were available showing the smoke charts.[6][7] In the United States, local ordinances in many cities were passed to prohibit smoke of greater than 3 (60% opacity) on the Ringelmann scale.[8]

Although these charts are still used informally, especially for educational purposes, they are largely obsolete. They are of little use for measuring modern, essentially invisible forms of urban air pollution and have effectively been replaced by more accurate, quantitative methods.[6][9][10] In the same way, modern emissions standards (such as the World Health Organization's air pollution guidelines and the US Environmental Protection Agency's Air Quality Standards) refer not to Ringelmann chart values, as they might once have done, but to the maximum allowed or recommended concentrations of different pollutants in the air.[11][12]

History of Rural Engineering

During 1900-1905, Ringelmann wrote a monumental, four-volume study Essai sur l’Histoire du Génie Rural (Essay on the History of Rural Engineering), which traced the progress of rural engineering from pre-history to the modern age.[1]: 51

Ringelmann effect

Ringelmann also discovered the Ringelmann effect, also known as "social loafing". This research was carried out at the agricultural school of Grand-Jouan, between 1882 and 1887, but the results were not published until 1913.[13][14] Specifically, Ringelmann had his students, individually and in groups, pull on a rope. He noticed that the effort exerted by a group was less than the sum of the efforts exerted by the students acting individually.[14]: 9

Original text : Pour l’emploi de l’homme, comme d’allieurs des animaux de trait, le meilleure utilisation est réalisée quand le moteur travaille seul : dès qu’on accouple deux ou plusieurs moteurs sur la même résistance, le travail utilisé de chacun d’eux, avec la même fatigue, diminue par suite du manque de simultanéité de leurs efforts …

Translation : When employing men, or draught animals, better use is achieved when the source of motive power works alone: as soon as one couples two or several such sources to the same load, the work performed by each of them, at the same level of fatigue, decreases as a result of the lack of simultaneity of their efforts …

This finding is one of the earliest discoveries in the history of Social Psychology, allowing Ringelmann to be described by some as a founder of Social Psychology.[15]

Max Ringelmann died in Paris on 2 May 1931.[16]

Bibliography

| Library resources about Max Ringelmann |

| By Max Ringelmann |

|---|

Ringelmann's publications include:

- Ringelmann, Maximilien, Les Machines Agricoles (Paris: Hachette, 1888–1898), 2 vol.s.

- Ringelmann, Maximilien, Les Travaux et Machines pour mise en Culture des Terres (Paris: Librarie agricole de la Maison rustique, 1902). (Reviewed in Revue des cultures coloniales, vol. 11, no. 110, pages 217-218 (October 5, 1902).)

- Ringelmann, Maximilien, Génie Rural Appliqué aux Colonies [Rural engineering applied in the colonies] (Paris: Augustin Challamel, 1908).

- Ringelmann, Maximilien, Recherches sur les moteurs animés. Travail de l'homme. Annales de l'Institut national agronomique. Tome VII. 1913. p. 2-40 (main publication about the so-called Rigelmann effect)

- Ringelmann, Maximilien, Puits Sondages et Sources [Well drilling and wellheads] (Paris, 1930).

References

- Simon, Bernard (1998). "Max Ringelmann (1861-1931) et la recherche en machinisme agricole". In Fontanon, Claudine (ed.). Histoire de la mécanique appliquée enseignement, recherche et pratiques mécaniciennes en France après 1880. Paris: ENS Editions. pp. 47–55. ISBN 2-902126-50-6. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Tissander, Gaston (May 26, 1888). "Obituary: Hervé Mangon". La Nature. 782: 401–403. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Grand Jouan is located roughly midway between the cities of Rennes and Nantes, France.

- Mareschal, G. (1891). "Testing-laboratory for agricultural machines". Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. Institution of Civil Engineers (Great Britain). 103: 455–456. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Hughes, Glyn (2010). "The Ringelmann smoke chart" (PDF). SOLIFTEC The Solid Fuel Technology Institute. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- IC 8333 - Ringelmann smoke chart (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of mines. 1 May 1967. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "Sensing change: Maximilien Ringelmann Smoke Charts 1897". Science history institute. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Bachmann, John (24 February 2012). "Will the Circle Be Unbroken: A History of the U.S. National Ambient Air Quality Standards" (PDF). Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 57 (6): 652–697. doi:10.3155/1047-3289.57.6.652. PMID 17608004. S2CID 44485450. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "BS 2742:2009 Use of the Ringelmann and miniature smoke charts". British Standards Institution. 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Uekoetter, F. (2005). "The strange career of the Ringelmann smoke chart". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 106 (1–3): 11–26. doi:10.1007/s10661-005-0756-z. PMID 16001709. S2CID 20228225.

- "Criteria Air Pollutants". US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- "Ambient (outdoor) air pollution". World Health Organization. 20 May 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- Kravitz, David A.; Martin, Barbara (1986). "Ringelmann rediscovered: The original article". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 50 (5): 936–941. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.936.

- Ringelmann, Maz (1913). "Recherches sur les moteurs animés: Travail de l'homme (Research on animate sources of power: The work of man)". Annales de l'Institut National Agronomique. 2 (12): 2–40. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Kassin, Saul; Fein, Steven; Markus, Hazel Rose (February 22, 2016). Social Psychology Front Cover (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. pp. 12–13. ISBN 9781305888340. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Wery, Georges (August 1931). "Nécrologie: Max Ringelmann" [Obituary: Max Ringelmann]. L'Agriculture pratique des pays chauds [Practical agriculture in hot countries]. 2nd series (in French). 14: 621–624.