May Declaration

The May Declaration (Slovene: Majniška deklaracija, Croatian: Svibanjska deklaracija, Serbian: Majska deklaracija/Мајска декларација) was a manifesto of political demands for unification of South Slav-inhabited territories within Austria-Hungary put forward to the Imperial Council in Vienna on 30 May 1917. It was authored by Anton Korošec, the leader of the Slovene People's Party. The document was signed by Korošec and thirty-two other council delegates representing South-Slavic lands within the Cisleithanian part of the dual monarchy – the Slovene Lands, the Dalmatia, Istria, and the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The delegates who signed the declaration were known as the Yugoslav Club.

| May Declaration | |

|---|---|

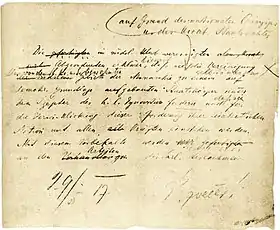

A draft of the May Declaration | |

| Presented | 30 May 1917 |

| Location | Vienna, Austria-Hungary |

| Author(s) | Anton Korošec |

| Signatories | 33 members of the Yugoslav Club in the Reichsrat |

The May Declaration was generally favourably greeted by Croat politicians in Croatia-Slavonia, but was met with opposition or indifference by the Bosniaks, the Bosnian Serbs, and the Croatian Serbs. The declaration also applied pressure on the government of the Kingdom of Serbia which saw the objectives of the declaration as a threat to fulfilment of its First World War goals in terms of territorial expansion. This led the Kingdom of Serbia government to give priority to the drafting of the Corfu Declaration, with the Yugoslav Committee outlining the principles of unification of a common state for all South Slavs living in Austria-Hungary, Serbia, and Montenegro at the time. The advocation of the May Declaration was banned by Austro-Hungarian authorities in May 1918.

Background

During the First World War, pressure developed in the parts of Austria-Hungary inhabited by the South Slavic population – the Croats, Serbs, Slovenes, and Bosniaks in support of a trialist reform,[2] or establishment of a common state of South Slavs independent of the empire. The latter was meant to be achieved through realisation of Yugoslavist ideas, and unification with the Kingdom of Serbia.[3]

Serbia considered the war an opportunity for territorial expansion. A committee tasked with determining war aims produced a programme to establish a Yugoslav state by the addition of South Slav-inhabited parts of the Habsburg lands – Croatia-Slavonia, Slovene Lands, Vojvodina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Dalmatia.[4] In the Niš Declaration, the National Assembly of Serbia announced the struggle to liberate and unify "unliberated brothers".[5] This aim was contravened by the Triple Entente, which favoured the existence of Austria-Hungary as a counterweight to influence of the German Empire.[6]

In 1915, the Yugoslav Committee was established as an ad-hoc group with no official capacity.[7] The committee, partially funded by the Serbian government, consisted of intellectuals and politicians from Austria-Hungary claiming to represent the interests of South Slavs.[8] Ante Trumbić served as president of the committee,[9] but its most prominent member was Frano Supilo, the co-founder of the ruling Croat-Serb Coalition (HSK) in Croatia-Slavonia. Supilo advocated a federation consisting of Serbia (including Vojvodina), Croatia (encompassing Croatia-Slavonia and Dalmatia), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, and Montenegro. At the same time, the committee learned that the Triple Entente promised the Kingdom of Italy territory (parts of the Slovene Lands, Istria, and Dalmatia) under the Treaty of London to forge an alliance with that nation.[10] Most of the committee members were from Dalmatia, and saw the Treaty of London as a threat that could only be checked with help from Serbia.[11]

International support only began to gradually shift away from the preservation of Austria-Hungary in 1917. That year, Russia sued for peace following the Russian Revolution, while the United States, whose President Woodrow Wilson advocated the principle of self-determination, entered the war.[11] Nonetheless, in his Fourteen Points speech, Wilson only promised autonomy for the peoples of Austria-Hungary. Preservation of the dual monarchy was not abandoned before the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918. By then, the allies became convinced that it could not resist the Communist revolution.[12]

Announcement and reception

South Slavic deputies on the Austro-Hungarian Imperial Council in Vienna organised themselves into the Yugoslav Parliamentary Group or the Yugoslav Club by following examples of similar grouping by their Polish and Czech colleagues. The deputies represented Cisleithanian lands (the Slovene Lands, Dalmatia, Istria, and Bosnia and Herzegovina). The Yugoslav Club there was chaired by the leader of the Slovene People's Party (SLS) Anton Korošec. Twenty-three club members were Slovenes, twelve were Croats, and two were Serbs. On 30 May 1917,[13] 33 members of the Yugoslav Club presented a declaration,[5] demanding unification of Habsburg lands inhabited by Croats, Slovenes, and Serbs into a democratic, free, and independent state organised as a Habsburg realm.[13] The signatories included Korošec, and two other prominent Slovenian political leaders – the Governor of the Duchy of Carniola, Ivan Šusteršič, and Janez Evangelist Krek.[14] The demand was made with references to the principles of national self-determination and Croatian state right.[13]

The May Declaration was first welcomed in Croatia by the Mile Starčević faction of the Party of Rights (SSP).[5] The SSP leader, Ante Pavelić, praised the declaration in the Croatian Sabor a week after its debut in Vienna as an expression of a democratic spirit awakened in Europe by enlightened Russia.[13] While publicly endorsing the declaration, Pavelić was fully aware that there would be no concessions from Vienna.[15] The Frankist faction of the SSP, organised as the Pure Party of Rights and led by Aleksandar Horvat, did not endorse the declaration, but declared that it would not hinder the efforts of those supporting the declaration. The Croatian People's Peasant Party leader Stjepan Radić offered only lukewarm support. A particularly strong support for the declaration came from Antun Bauer, the then Archbishop of Zagreb.[5] The HSK, as the ruling party in Croatia-Slavonia, and its co-founder and leader Svetozar Pribičević, ignored the May Declaration.[12]

The declaration was opposed by Bosniak leaders such as the president of the Diet of Bosnia, Safvet-beg Bašagić. A counter-proposal was submitted to the Emperor, whereby Bosnia and Herzegovina would be attached to Hungary and given a degree of autonomy. The Bosnian Serbs were reserved, while the Croatian Serbs largely opposed the declaration demands. The declaration was also criticised by some Roman Catholics, such as Krek, who preferred a unified state outside Habsburg realms.[2]

The May Declaration was debated for a year. In May 1918, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Krk Anton Mahnič wrote a series of newspaper articles supporting the declaration's aims. Mahnič deemed the establishment of a common South Slavic polity of some sort inevitable and was predominantly concerned with issues of "ethnic and confessional cohabitation" in such a state. His efforts, as well as those of other proponents of the declaration, came to an end on 12 May 1918 when imperial authorities prohibited further advocation of the May Declaration.[2]

Impact

.jpg.webp)

The May Declaration had a significant impact. Besides moving the issue of South Slavic unification beyond its Croatian framework and demonstrating that the Slovenian political actors were not necessarily loyal to the empire, the declaration impacted the thinking of authorities in Serbia and of the Yugoslav Committee.[16] The declaration also reaffirmed the position of Croatian Serbs as political group in Croatia.[14]

The Triple Entente was looking for ways to achieve a separate peace with Austria-Hungary and thereby detach it from Germany presenting the Serbian government – exiled on the Greek island of Corfu – with a problem. It was faced with the substantial risk of a trialist solution of the South Slavic lands within Austria-Hungary in the case of such a separate peace treaty, thereby cancelling any chance of fulfilment of the proclaimed Serbian war objectives.[17]

The Yugoslav Committee was also placed under pressure. It claimed to speak on behalf of South Slavs within Austria-Hungary, but it was openly looking after its own interests. The challenge presented by the May Declaration to the Yugoslav Committee and the government of Serbia, depriving them of the initiative in the South Slavic unification process, led the two to consider the drafting of a programme of unification of South Slavic lands in Austria-Hungary and outside of it a priority. They held a series of meetings on Corfu from 15 June to 20 July, attempting to reach consensus despite radically different views on the system of government in the proposed common state. No agreement on the issue was reached, so the resulting Corfu Declaration glossed over the matter, leaving it to the Constituent Assembly to decide by an unspecified qualified majority.[18]

On 2–3 March 1918, a conference was held in Zagreb attended, among others, by representatives of SSP, the SLS, the National Progressive Party, and HSK dissidents. The meeting produced the Zagreb Resolution on political unification of South Slavs.[19] As the central authority of Austria-Hungary gradually disintegrated in 1918, provincial national councils were established (including one for Slovenia by the Yugoslav Club) to fill the power vacuum, introducing a parallel administration by July. By October, the National Council of the Slovenes, Serbs, and Croats was established in Zagreb as a de facto government of the South Slavic lands in Austria-Hungary.[20]

References

- Headlam 1911, pp. 2–39.

- Ramet 2006, pp. 40–41.

- Pavlowitch 2003, pp. 27–28.

- Pavlowitch 2003, p. 29.

- Ramet 2006, p. 40.

- Pavlowitch 2003, pp. 33–35.

- Ramet 2006, p. 43.

- Ramet 2006, p. 41.

- Glenny 2012, p. 368.

- Ramet 2006, pp. 41–42.

- Pavlowitch 2003, p. 31.

- Banac 1984, p. 126.

- Pavlowitch 2003, p. 32.

- Banac 1984, p. 125.

- Banac 1984, pp. 125–126.

- Pavlowitch 2003, pp. 32–33.

- Pavlowitch 2003, p. 33.

- Pavlowitch 2003, pp. 33–34.

- Matijević 2008, pp. 53–54.

- Pavlowitch 2003, pp. 35–36.

Sources

- Banac, Ivo (1984). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1675-2.

- Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans, 1804–2012: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers. Toronto: House of Anansi Press. ISBN 978-1-77089-273-6.

- Headlam, James Wycliffe (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–39.

- Matijević, Zlatko (2008). "The National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs in Zagreb (1918/1919)". Review of Croatian History. Zagreb: Hrvatski institut za povijest. 4 (1): 51–84. ISSN 1845-4380.

- Pavlowitch, Kosta St. (2003). "The First World War and Unification of Yugoslavia". In Djokic, Dejan (ed.). Yugoslavism: Histories of a Failed Idea, 1918–1992. London: C. Hurst & Co. pp. 27–41. ISBN 1-85065-663-0.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253346568.