J. Mayo Williams

Jay Mayo "Ink" Williams (September 25, 1894 – January 2, 1980) was a pioneering African-American producer of recorded blues music. Some historians have claimed that Ink Williams earned his nickname by his ability to get the signatures of talented African-American musicians on recording contracts,[1] but in fact it was a racial sobriquet from his football days, when he was a rare Black player on white college and professional teams.[2] He was the most successful "race records" producer of his time, breaking all previous records for sales in this genre.

Williams in 1920 | |

| Born: | September 25, 1894 Pine Bluff, Arkansas |

|---|---|

| Died: | January 2, 1980 (aged 85) Chicago, Illinois |

| Career information | |

| Position(s) | End |

| Height | 5 ft 11 in (180 cm) |

| Weight | 174 lb (79 kg) |

| College | Brown |

| Career history | |

| As player | |

| 1921 | Canton Bulldogs |

| 1921–1923 | Hammond Pros |

| 1924 | Dayton Triangles |

| 1924 | Hammond Pros |

| 1925 | Cleveland Bulldogs |

| 1925–1926 | Hammond Pros |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1917–1919 |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

Biography

Williams was born in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the son of Millie and Daniel Williams.[lower-alpha 1] When he was seven years old, his father was murdered, and the family returned to his mother's hometown of Monmouth, Illinois, where he grew up.

Williams attended Brown University, where he was a track star and outstanding football player. He also served in the First World War.[lower-alpha 2] During the 1920s, he played professional football and was one of three black athletes (along with Paul Robeson) to play in the fledgling National Football League during its first year. His playing career lasted until 1926. During that span he played for the Canton Bulldogs, the Dayton Triangles, the Hammond Pros and the Cleveland Bulldogs.

After graduating in 1921, he moved to Chicago. Although he continued to play football until 1926, his first love was music, and in 1924 he joined Paramount Records, which had recently begun to produce and market "race" records.[3] Williams became a talent scout and supervisor of recording sessions in the Chicago area, becoming the most successful blues producer of his time. Two of his biggest discoveries as recording artists were the singer Ma Rainey – already a popular live performer – and Papa Charlie Jackson, the first commercially successful self-accompanied blues singer. He recorded Blind Lemon Jefferson, Tampa Red, Thomas A. Dorsey, Ida Cox, Jimmy Blythe, Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver, and Freddy Keppard.[3] He also managed a crew of songwriters, including Tiny Parham.

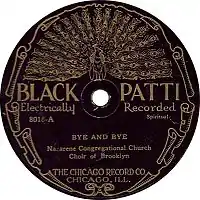

In 1927, he left Paramount and started The Chicago Record Company, releasing jazz, blues and gospel records on the "Black Patti" label.[3] One of these releases was The Down Home Boys' "Original Stack O' Lee Blues", believed to be the first recorded version of the song better known as "Stagger Lee", and of which only one copy is now known to exist. Black Patti soon failed, and Williams moved to Brunswick Records and its subsidiary label Vocalion, where he recorded Clarence "Pine Top" Smith and Leroy Carr, among others.[3] However, after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, record sales plummeted, and Williams found new work as a football coach at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

In 1934, Williams was hired as head of the "race records" department at Decca,[3] where he recorded such musicians as Mahalia Jackson, Alberta Hunter, Blind Boy Fuller, Roosevelt Sykes, Sleepy John Estes, Kokomo Arnold, Peetie Wheatstraw, Bill Gaither, Bumble Bee Slim, Georgia White, Trixie Smith, Monette Moore, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Marie Knight, Tab Smith as well as pioneering the recording of the increasingly popular small group sound with such groups as The Harlem Hamfats.

Williams was accused by some black musicians of a "dicty" attitude[4] – that is, acting as though he was a member of the white middle class. His efforts to refine the articulation of rural blues artists and polish their images were often met with hostility and misunderstanding. In addition to producing, he also managed some of the many artists he recorded, even sharing ownership of some songs as a co-writer. Songs on which he is credited as co-writer include "Corrine, Corrina", Nellie Lutcher's "Fine Brown Frame", Louis Jordan's "Mop Mop", "Keep A Knocking" Bert Mays and Stick McGhee's "Drinkin' Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee" among others.

Williams set up the Chicago Music Publishing Company (CMPC) as publisher for all the titles he recorded. The CMPC collected all royalties generated by the materials it held copyrights on, and was responsible for passing on some of the profits to the composer or performer. However, many successful artists that Williams recorded, including Blind Blake and Blind Lemon Jefferson, probably never received any royalties. Race record entrepreneurs knew that rural blues musicians were unfamiliar with copyright laws, and they further played upon the musicians' vulnerability by providing free liquor at recording sessions, hoping they would get drunk and sign their rights away.[1]

_at_Burr_Oak_Cemetery%252C_Alsip%252C_IL.jpg.webp)

After leaving Decca in 1945, Williams worked freelance and ran several small, independent labels.[3] From 1945 through 1949, he ran the Harlem label (based in New York City), and the Chicago, Southern, and Ebony label (based in Chicago); one of the artists he recorded was the young Muddy Waters.[3] After a period of freelance producing, he reopened the Ebony label in 1952 and kept it going through the early 1970s, recording Lil Armstrong, Bonnie Lee, Oscar Brown and Hammie Nixon.[5]

As plans were being initiated to conduct interviews with Williams to gather his life story in 1980, he died in a Chicago nursing home. He was buried at Burr Oak Cemetery in Alsip, Illinois.

Legacy

Williams was a member of the National Football Hall of Fame Association. In 2004, he was posthumously inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame.[6]

Notes

- Most sources state that he was born in Monmouth, Illinois. This is incorrect; see talk page.

- See talk page.

References

- Barlow, William (1989). "Looking Up at Down": The Emergence of Blues Culture. Temple University Press. pp. 131–132. ISBN 0-87722-583-4.

- Whitman, Burt (October 19, 1919) "22,000 See Brown Hold Harvard to a 7 to 0 Victory", Boston Herald. p. 17.

- Colin Larkin, ed. (1995). The Guinness Who's Who of Blues (Second ed.). Guinness Publishing. pp. 379/380. ISBN 0-85112-673-1.

- Jim Dawson; Steve Propes (1992). What Was the First Rock 'n' Roll Record?. Boston & London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-12939-0.

- Clemson.edu Archived June 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "2004 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees". Blues Foundation. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

External links

- Biography

- Carroll, Bob (1995). "Doc Yound and the Hammond Pros" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association. 17 (1): 1–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2010.

- Charliegillett.com (Special tribute to his life)