McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System

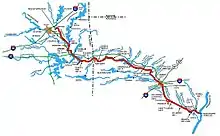

The McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System (MKARNS) is part of the United States inland waterway system originating at the Tulsa Port of Catoosa and running southeast through Oklahoma and Arkansas to the Mississippi River. The total length of the system is 445 miles (716 km).[1] It was named for two senators, Robert S. Kerr (D-OK) and John L. McClellan (D-AR), who pushed its authorizing legislation through Congress. The system officially opened on June 5, 1971. President Richard M. Nixon attended the opening ceremony.[1] It is operated by the Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).[2]

| McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System | |

|---|---|

Big Dam Bridge is a footbridge built atop the Murray Lock and Dam in Little Rock, Arkansas. | |

| Specifications | |

| Locks | 18 (originally 17) (Lock #11 was never constructed; Montgomery Point (Lock #99) was added after construction was completed) |

| Navigation authority | Army Corps of Engineers |

| History | |

| Construction began | 1963 |

| Date of first use | January 1971 |

| Date completed | 1970 |

| Geography | |

| End point | Tulsa Port of Catoosa |

| Branch(es) | Arkansas Post Canal |

While the system primarily follows the Arkansas River, it also includes portions of the Verdigris River in Oklahoma, the White River in Arkansas, and the Arkansas Post Canal, a short canal named for the nearby Arkansas Post National Memorial which connects the Arkansas and White Rivers.

Through Oklahoma and Arkansas, dams artificially deepen and widen the modest-sized river to build it into a commercially navigable body of water. The design enables traffic to overcome an elevation difference of 420 feet (130 m) between the Mississippi River and the Tulsa Port of Catoosa.[2] Along the section of the Arkansas River that carries the McClellan–Kerr channel, the river sustains commercial barge traffic and offers passenger and recreational use. Here, the system is a series of reservoirs.

Official change of significance

The U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) officially announced in early May 2015 that it had upgraded MKARNS from "Connector" to "Corridor" on the National Marine Highway. The announcement also added the Oklahoma Department of Transportation (ODOT) as an official sponsor.[3][lower-alpha 1] [lower-alpha 2]

In 2015, the USACE increased its designation of the MKARNS from a moderate-use to a high-use waterway system. The high-use designation means that a waterway carries more than 10 million tons per year, having a value of more than 12 million ton-miles per year.[3]

Construction

The Arkansas River is very shallow through Arkansas and Oklahoma, and was naturally incapable of supporting river traffic through most of the year. To allow for navigation, construction was started in 1963 on a system of channels and locks to connect the many reservoirs along the length of the Arkansas River. The first section, running to Little Rock, Arkansas, opened on January 1, 1969. The first barge to reach the Port of Catoosa arrived in early 1971.

Each lock measures 110 feet (34 m) wide and 600 feet (180 m) long, the standard size for much of the Mississippi River waterway. Standard jumbo barges, measuring 35 by 195 feet (59 m), are grouped 3 wide by 3 long, with a tug at center rear, to form a barge tow which can be fit into a lock. Larger barge tows must be broken down and passed through the lock in sections, and rejoined on the opposite side.[4]

The specifications for the channel itself are as follows:

- Depth of channel: 9 ft (2.7 m) or more.

- Width of channel: mostly 250 ft (76 m) to 300 ft (91 m).

- Bridge clearance: 300 ft (91 m) horizontal; 52 ft (16 m) vertical.

Although Congress originally authorized USACE to dredge the channel to a depth of 12 ft (3.7 m) in 2005, it did not provide the funds to do so. ODOT says that the capacity of each barge could be increased by 200 tons for each foot of draft.[4] An article in 2010 stated that much of MKARNS is already 12 feet (3.7 m) deep, so that only about 75 miles (121 km) would need to be deepened. The article quoted Lt. Col. Gene Snyman, then deputy commander of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Tulsa District, as saying such a project would cost about $170 million (2010 dollars).[5]

Lock information

The following tables list the features of the navigation system, from the Mississippi River to the origin at the Port of Catoosa. Except as noted, all locks are on the Arkansas River.

There is no lock 11; sequentially, it would have been in the middle of Lake Dardanelle. Per the animated system map (see "External links"), Dardanelle Lock & Dam (lock 10), which forms Lake Dardanelle, is the highest facility on the system (54 feet between upper & lower pools); Ozark-Jeta Taylor Lock & Dam (lock 12), just above that lake, is the third highest (34 feet). Thus, it is likely that those two facilities were redesigned, in terms of height and possibly location, so as to eliminate lock 11 as originally planned. The Mississippi River lock is numbered lock 99 as it was added to the system after it was completed.

| Feature | Navigational distance from Mississippi River | Location | Coordinates | Photo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas | |||||

| Montgomery Point Lock and Dam (Lock 99) | 0.5 mi (0.80 km) | White River | 33°56′45″N 91°05′13″W |  | | | |

| Norrell Lock and Dam (Lock 1) | 10.3 mi (16.6 km) | Arkansas Post Canal | 34°01′10″N 91°11′40″W |  | |

| Lock 2 | 13.3 mi (21.4 km) | Arkansas Post Canal | 34°01′34″N 91°14′45″W | ||

| Wilbur D. Mills Dam | 19 mi (31 km) | Arkansas County /Desha County | 33°59′20″N 91°18′47″W |  | |

| Joe Hardin Lock and Dam (Lock 3) | 50.2 mi (80.8 km) | Jefferson County | 34°09′49″N 91°40′40″W |  | |

| Emmett Sanders Lock and Dam (Lock 4) | 66.0 mi (106.2 km) | Pine Bluff | 34°14′49″N 91°54′19″W | ||

| Col. Charles D. Maynard Lock and Dam (Lock 5) | 86.3 mi (138.9 km) | Jefferson County | 34°24′46″N 92°06′03″W | ||

| David D. Terry Lock and Dam (Lock 6) | 108.1 mi (174.0 km) | Pulaski County | 34°39′58″N 92°09′23″W | ||

| Murray Lock and Dam Lock 7 | 125.4 mi (201.8 km) | Little Rock | 34°47′25″N 92°21′28″W |  | |

| Toad Suck Ferry Lock and Dam (Lock 8) | 155.9 mi (250.9 km) | Conway | 35°04′35″N 92°32′23″W | ||

| Arthur V. Ormond Lock and Dam (Lock 9) | 176.9 mi (284.7 km) | Morrilton | 35°07′30″N 92°47′09″W | ||

| Dardanelle Lock and Dam (Lock 10) | 205.5 mi (330.7 km) | Dardanelle /Russellville | 35°15′00″N 93°10′07″W | .jpg.webp) | |

| Lock 11 | Never Constructed | ||||

| Ozark-Jeta Taylor Lock and Dam (Lock 12)[lower-alpha 3] | 256.8 mi (413.3 km) | Ozark | 35°28′17″N 93°48′46″W | ||

| James W. Trimble Lock and Dam (Lock 13)[lower-alpha 4] | 292.8 mi (471.2 km) | Barling | 35°20′55″N 94°17′52″W | ||

| Oklahoma | |||||

| W. D. Mayo Lock and Dam (Lock 14) | 319.6 mi (514.3 km) | Fort Coffee | 35°18′52″N 94°33′33″W |  | |

| Robert S. Kerr Lock and Dam (Lock 15) | 336.2 mi (541.1 km) | Sallisaw | 35°20′54″N 94°46′40″W |  | |

| Webbers Falls Lock and Dam (Lock 16) | 366.7 mi (590.1 km) | Webbers Falls | 35°33′14″N 95°10′02″W |  | |

| Chouteau Lock & Dam (Lock 17) | 401.4 mi (646.0 km) | Wagoner (Verdigris River) | 35°51′25″N 95°22′14″W |  | |

| Newt Graham Lock and Dam (Lock 18) | 421.6 mi (678.5 km) | Inola (Verdigris River) | 36°03′31″N 95°32′11″W |  | |

| Port of Catoosa | 445 mi (716 km) | Catoosa (Verdigris River) | 36°14′28″N 95°44′15″W |  | |

2019 Arkansas River flooding

Extremely heavy rains hit the Arkansas River upstream of Keystone Dam during late May and early June 2019. So much water poured into the Keystone Reservoir in a short time that it quickly became evident that a major release of water would be needed to prevent overtopping the dam, causing devastating floods downstream. Even so, water rushed downstream toward MKARNS at such a high rate that officials at USACE halted barge traffic to avoid calamities such as collisions or hitting trees and debris afloat in the river.[7]

By October, barge traffic was allowed on a limited basis. Normally, tows comprise twelve to sixteen barges. However, the flood carried so much silt down river that re-dredging would be required to return to normal traffic patterns. In October, the tows were limited to six barges (two wide and three deep).[7]

The 2019 flood deposited about 1.5 million cubic yards of sediment into the waterway, As of February 2020, barge traffic remained limited by tow size and restricted to daylight hours only due to sediment. USACE expected to complete the dredging of sediment by late May 2020.[8]

Waterway traffic control

The growth of business along MKARNS has greatly increased congestion at the locks. The Secretary of the Army has directed USACE to establish the following priorities for admitting vessels to each lock:

- Vessels owned by the U.S. government

- Commercial passenger vessels

- Commercial vessels (e.g., barges)

- Rafts

- Pleasure craft

There is no minimum size for watercraft using the locks. Craft as small as canoes, dinghies, and kayaks have all been allowed to use the locks, either alone or with multiple other vessels at the same time. If commercial traffic is heavy, pleasure craft may be required to wait approximately 1.5 hours or may be allowed to lock through with commercial vessels.[9]

See also

Notes

- The Arkansas Department of Transportation had previously been designated as an official sponsor.

- According to Senator James Inhofe, (R-OK), The change of status will increase support for funding to ... "improve reliability in navigation, hydropower generation and flood risk reduction".[3]

- The reservoir created by Ozark-Jeta Taylor Lock and Dam is named Ozark Lake.[6]

- John Paul Hammerschmidt Lake was created by the completion of James W. Trimble Lock & Dam. The lake is 26 miles (42 km) long with the dam and half its length in Arkansas and the other half of its length in Oklahoma.[6]

References

- O'Dell, Larry. "McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

- "U. S. Army Corps of Engineers Little Rock District. MKARNS". Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2007.

- "Oklahoma Waterway Takes Prestigious Step Up in National Status (PRESS RELEASE)". U.S. Department of Transportation. May 15, 2015.

- "McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System 2016 Inland Waterway Fact Sheet". Oklahoma Department of Transportation. 2016. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- Kramer, Kirk (October 17, 2010). "Going deeper – Deeper channel would boost business". Muskogee Phoenix. Accessed June 20, 2017.

- Townsend, Jay (November 17, 2015). "11 Great Things about the Arkansas River in Arkansas". Pacesetter Live. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- Morgan, Rhett (October 11, 2019). "Limited waterway traffic returns to McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System". Tulsa World. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- Morgan, Rhett (February 25, 2020). "Commercial navigation still faces restrictions on Arkansas River waterway". Tulsa World. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- https://www.swl.usace.army.mil/Portals/50/docs/navigation/Turtle%20Book%20or%20Locking%20Through%20Book.pdf

External links

- Map of navigation system

- History of the Arkansas River

- US Army Corps of Engineers, Little Rock, Arkansas district navigation information

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory