Medieval Greek

Medieval Greek (also known as Middle Greek, Byzantine Greek, or Romaic) is the stage of the Greek language between the end of classical antiquity in the 5th–6th centuries and the end of the Middle Ages, conventionally dated to the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

| Medieval Greek | |

|---|---|

| Byzantine Greek, Romaic | |

Ῥωμαϊκή Rhōmaïkḗ Romaïkí | |

| Region | Eastern Mediterranean (Byzantine Empire) |

| Era | c. 600–1500 AD; developed into Modern Greek[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Greek alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | grc |

| ISO 639-3 | grc (i.e. with Ancient Greek[2]) |

qgk | |

| Glottolog | medi1251 |

From the 7th century onwards, Greek was the only language of administration and government in the Byzantine Empire. This stage of language is thus described as Byzantine Greek. The study of the Medieval Greek language and literature is a branch of Byzantine studies, the study of the history and culture of the Byzantine Empire.

The beginning of Medieval Greek is occasionally dated back to as early as the 4th century, either to 330 AD, when the political centre of the Roman Empire was moved to Constantinople, or to 395 AD, the division of the empire. However, this approach is rather arbitrary as it is more an assumption of political, as opposed to cultural and linguistic, developments. Indeed, by this time the spoken language, particularly pronunciation, had already shifted towards modern forms.[1]

The conquests of Alexander the Great, and the ensuing Hellenistic period, had caused Greek to spread to peoples throughout Anatolia and the Eastern Mediterranean, altering the spoken language's pronunciation and structure.

Medieval Greek is the link between this vernacular, known as Koine Greek, and Modern Greek. Though Byzantine Greek literature was still strongly influenced by Attic Greek, it was also influenced by vernacular Koine Greek, which is the language of the New Testament and the liturgical language of the Greek Orthodox Church.

History and development

Constantine (the Great) moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium (renamed Constantinople) in 330. The city, though a major imperial residence like other cities such as Trier, Milan and Sirmium, was not officially a capital until 359. Nonetheless, the imperial court resided there and the city was the political centre of the eastern parts of the Roman Empire where Greek was the dominant language. At first, Latin remained the language of both the court and the army. It was used for official documents, but its influence waned. From the beginning of the 6th century, amendments to the law were mostly written in Greek. Furthermore, parts of the Roman Corpus Iuris Civilis were gradually translated into Greek. Under the rule of Emperor Heraclius (610–641 AD), who also assumed the Greek title Basileus (Greek: βασιλεύς, 'monarch') in 610, Greek became the official language of the Eastern Roman Empire.[4] This was in spite of the fact that the inhabitants of the empire still considered themselves Rhomaioi ('Romans') until its end in 1453,[5] as they saw their State as the perpetuation of Roman rule. Latin continued to be used on the coinage until the ninth century and in certain court ceremonies for even longer.

Despite the absence of reliable demographic figures, it has been estimated that less than one third of the inhabitants of the Eastern Roman Empire, around eight million people, were native speakers of Greek.[6] The number of those who were able to communicate in Greek may have been far higher. The native Greek speakers consisted of many of the inhabitants of the southern Balkan Peninsula, south of the Jireček Line, and all of the inhabitants of Asia Minor, where the native tongues (Phrygian, Lycian, Lydian, Carian etc.), except Armenian in the east, had become extinct and replaced by Greek by the 5th century.

In any case, all cities of the Eastern Roman Empire were strongly influenced by the Greek language.[7]

In the period between 603 and 619, the southern and eastern parts of the empire (Syria, Egypt, North Africa) were occupied by Persian Sassanids and, after being recaptured by Heraclius in the years 622 to 628, were conquered by the Arabs in the course of the Muslim conquests a few years later.

Alexandria, a centre of Greek culture and language, fell to the Arabs in 642. During the seventh and eighth centuries, Greek was gradually replaced by Arabic as an official language in conquered territories such as Egypt,[7] as more people learned Arabic. Thus, the use of Greek declined early on in Syria and Egypt. The invasion of the Slavs into the Balkan Peninsula reduced the area where Greek and Latin was spoken (roughly north of a line from Montenegro to Varna on the Black Sea in Bulgaria). Sicily and parts of Magna Graecia, Cyprus, Asia Minor and more generally Anatolia, parts of the Crimean Peninsula remained Greek-speaking. The southern Balkans which would henceforth be contested between Byzantium and various Slavic kingdoms or empires. The Greek language spoken by one-third of the population of Sicily at the time of the Norman conquest 1060–1090 remained vibrant for more than a century, but slowly died out (as did Arabic) to a deliberate policy of Latinization in language and religion from the mid-1160s.

From the late 11th century onwards, the interior of Anatolia was invaded by Seljuq Turks, who advanced westwards. With the Ottoman conquests of Constantinople in 1453, the Peloponnese in 1459 or 1460, the Empire of Trebizond in 1461, Athens in 1465, and two centuries later the Duchy of Candia in 1669, the Greek language lost its status as a national language until the emergence of modern Greece in the year 1821. Language varieties after 1453 are referred to as Modern Greek.

Diglossia

As early as in the Hellenistic period, there was a tendency towards a state of diglossia between the Attic literary language and the constantly developing vernacular Koine. By late antiquity, the gap had become impossible to ignore. In the Byzantine era, written Greek manifested itself in a whole spectrum of divergent registers, all of which were consciously archaic in comparison with the contemporary spoken vernacular, but in different degrees.[8]

They ranged from a moderately archaic style employed for most every-day writing and based mostly on the written Koine of the Bible and early Christian literature, to a highly artificial learned style, employed by authors with higher literary ambitions and closely imitating the model of classical Attic, in continuation of the movement of Atticism in late antiquity. At the same time, the spoken vernacular language developed on the basis of earlier spoken Koine, and reached a stage that in many ways resembles present-day Modern Greek in terms of grammar and phonology by the turn of the first millennium AD. Written literature reflecting this Demotic Greek begins to appear around 1100.

Among the preserved literature in the Attic literary language, various forms of historiography take a prominent place. They comprise chronicles as well as classicist, contemporary works of historiography, theological documents, and saints' lives. Poetry can be found in the form of hymns and ecclesiastical poetry. Many of the Byzantine emperors were active writers themselves and wrote chronicles or works on the running of the Byzantine state and strategic or philological works.

Furthermore, letters, legal texts, and numerous registers and lists in Medieval Greek exist. Concessions to spoken Greek can be found, for example, in John Malalas's Chronography from the 6th century, the Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor (9th century) and the works of Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (mid-10th century). These are influenced by the vernacular language of their time in choice of words and idiom, but largely follow the models of written Koine in their morphology and syntax.

The spoken form of Greek was called γλῶσσα δημώδης (glōssa dēmōdēs 'vernacular language'), ἁπλοελληνική (haploellēnikē 'basic Greek'), καθωμιλημένη (kathōmilēmenē 'spoken') or Ῥωμαιϊκή (Rhōmaiïkē 'Roman language'). Before the 13th century, examples of texts written in vernacular Greek are very rare. They are restricted to isolated passages of popular acclamations, sayings, and particularly common or untranslatable formulations which occasionally made their way into Greek literature. Since the end of the 11th century, vernacular Greek poems from the literary realm of Constantinople are documented.

The Digenes Akritas, a collection of heroic sagas from the 12th century that was later collated in a verse epic, was the first literary work completely written in the vernacular. The Greek vernacular verse epic appeared in the 12th century, around the time of the French romance novel, almost as a backlash to the Attic renaissance during the dynasty of the Komnenoi in works like Psellos's Chronography (in the middle of the 11th century) or the Alexiad, the biography of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos written by his daughter Anna Komnena about a century later. In fifteen-syllable blank verse (versus politicus), the Digenes Akritas deals with both ancient and medieval heroic sagas, but also with stories of animals and plants. The Chronicle of the Morea, a verse chronicle from the 14th century, is unique. It has also been preserved in French, Italian and Aragonese versions, and covers the history of Frankish feudalism on the Peloponnese during the Latinokratia of the Principality of Achaea, a crusader state set up after the Fourth Crusade and the 13th century fall of Constantinople.

The earliest evidence of prose vernacular Greek exists in some documents from southern Italy written in the tenth century. Later prose literature consists of statute books, chronicles and fragments of religious, historical and medical works. The dualism of literary language and vernacular was to persist until well into the 20th century, when the Greek language question was decided in favor of the vernacular in 1976.

Dialects

The persistence until the Middle Ages of a single Greek speaking state, the Byzantine Empire, meant that, unlike Vulgar Latin, Greek did not split into separate languages. However, with the fracturing of the Byzantine state after the turn of the first millennium, newly isolated dialects such as Mariupol Greek, spoken in Crimea, Pontic Greek, spoken along the Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, and Cappadocian, spoken in central Asia Minor, began to diverge. In Griko, a language spoken in the southern Italian exclaves, and in Tsakonian, which is spoken on the Peloponnese, dialects of older origin continue to be used today. Cypriot Greek was already in a literary form in the late Middle Ages, being used in the Assizes of Cyprus and the chronicles of Leontios Makhairas and Georgios Boustronios.

Phonetics and phonology

It is assumed that most of the developments leading to the phonology of Modern Greek had either already taken place in Medieval Greek and its Hellenistic period predecessor Koine Greek, or were continuing to develop during this period. Above all, these developments included the establishment of dynamic stress, which had already replaced the tonal system of Ancient Greek during the Hellenistic period. In addition, the vowel system was gradually reduced to five phonemes without any differentiation in vowel length, a process also well begun during the Hellenistic period. Furthermore, Ancient Greek diphthongs became monophthongs.

Vowels

| Type | Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | rounded | |

| Close | /i/ ι, ει, η | (/y/) υ, οι, υι | /u/ ου |

| Mid | /e̞/ ε, αι | /o̞/ ο, ω | |

| Open | /a/ α | ||

The Suda, an encyclopedia from the late 10th century, gives some indication of the vowel inventory. Following the antistoichic[Note 1] system, it lists terms alphabetically but arranges similarly pronounced letters side by side. In this way, for indicating homophony, αι is grouped together with ε /e̞/; ει and η together with ι /i/; ο with ω /o̞/, and οι with υ /y/. At least in educated speech, the vowel /y/, which had also merged with υι, likely did not lose lip-rounding and become /i/ until the 10th/11th centuries. Up to this point, transliterations into Georgian continue using a different letter for υ/οι than for ι/ει/η,[11] and in the year 1030, Michael the Grammarian could still make fun of the bishop of Philomelion for confusing ι for υ.[12] In the 10th century, Georgian transliterations begin using the letter representing /u/ (უ) for υ/οι, in line with the alternative development in certain dialects like Tsakonian, Megaran and South Italian Greek where /y/ reverted to /u/. This phenomenon perhaps indirectly indicates that the same original phoneme had merged with /i/ in mainstream varieties at roughly the same time (the same documents also transcribe υ/οι with ი /i/ very sporadically).[13]

In the original closing diphthongs αυ, ευ and ηυ, the offglide [u] had developed into a consonantal [v] or [f] early on (possibly through an intermediate stage of [β] and [ɸ]). Before [n], υ turned to [m] (εὔνοστος ['evnostos] → ἔμνοστος ['emnostos], χαύνος ['xavnos] → χάμνος ['xamnos], ἐλαύνω [e'lavno] → λάμνω ['lamno]), and before [m] it was dropped (θαῦμα ['θavma] → θάμα ['θama]). Before [s], it occasionally turned to [p] (ἀνάπαυση [a'napafsi] → ἀνάπαψη [a'napapsi]).[14]

Words with initial vowels were often affected by apheresis: ἡ ἡμέρα [i i'mera] → ἡ μέρα [i 'mera] ('the day'), ἐρωτῶ [ero'to] → ρωτῶ [ro'to] ('(I) ask').[15]

A regular phenomenon in most dialects is synizesis ("merging" of vowels). In many words with the combinations [ˈea], [ˈeo], [ˈia] and [ˈio], the stress shifted to the second vowel, and the first became a glide [j]. Thus: Ῥωμαῖος [ro'meos] → Ῥωμιός [ro'mɲos] ('Roman'), ἐννέα [e'nea] → ἐννιά [e'ɲa] ('nine'), ποῖος ['pios] → ποιός ['pços] ('which'), τα παιδία [ta pe'ðia] → τα παιδιά [ta pe'ðʝa] ('the children'). This accentual shift is already reflected in the metre of the 6th century hymns of Romanos the Melodist.[16] In many cases, the vowel o disappeared in the endings -ιον [-ion] and -ιος [-ios] (σακκίον [sa'cion] → σακκίν [sa'cin], χαρτίον [xar'tion] → χαρτίν [xar'tin], κύριος ['cyrios] → κύρις ['cyris]). This phenomenon is attested to have begun earlier, in the Hellenistic Koine Greek papyri.[17]

Consonants

The shift in the consonant system from voiced plosives /b/ (β), /d/ (δ), /ɡ/ (γ) and aspirated voiceless plosives /pʰ/ (φ), /tʰ/ (θ), /kʰ/ (χ) to corresponding fricatives (/v, ð, ɣ/ and /f, θ, x/, respectively) was already completed during Late Antiquity. However, the original voiced plosives remained as such after nasal consonants, with [mb] (μβ), [nd] (νδ), [ŋɡ] (γγ). The velar sounds /k, x, ɣ, ŋk, ŋɡ/ (κ, χ, γ, γκ, γγ) were realised as palatal allophones ([c, ç, ʝ, ɲc, ɲɟ]) before front vowels. The fricative /h/, which had been present in Classical Greek, had been lost early on, although it continued to be reflected in spelling through the rough breathing, a diacritic mark added to vowels.[18]

Changes in the phonological system mainly affect consonant clusters that show sandhi processes. In clusters of two different plosives or two different fricatives, there is a tendency for dissimilation such that the first consonant becomes a fricative and/or the second becomes a plosive ultimately favoring a fricative-plosive cluster. But if the first consonant was a fricative and the second consonant was /s/, the first consonant instead became a plosive, favoring a plosive-/s/ cluster.[19] Medieval Greek also had cluster voicing harmony favoring the voice of the final plosive or fricative; when the resulting clusters became voiceless, the aforementioned sandhi would further apply. This process of assimilation and sandhi was highly regular and predictable, forming a rule of Medieval Greek phonotactics that would persist into Early Modern Greek. When dialects started deleting unstressed /i/ and /u/ between two consonants (such as when Myzithras became Mystras), new clusters were formed and similarly assimilated by sandhi; on the other hand it is arguable that the dissimilation of voiceless obstruents occurred before the loss of close vowels, as the clusters resulting from this development do not necessarily undergo the change to [fricative + stop], e.g. κ(ου)τί as [kti] not [xti].[20]

The resulting clusters were:

For plosives:

- [kp] → [xp]

- [kt] → [xt] (νύκτα ['nykta] → νύχτα ['nixta])

- [pt] → [ft] (ἑπτά [e'pta] → ἑφτά [e'fta])

For fricatives where the second was not /s/:

- [sθ] → [st] (Μυζ(η)θράς [myz(i)'θras] → Μυστράς [mi'stras])

- [sf] → [sp] (only occurred in Pontic Greek)[21]

- [sx] → [sk] (σχολείο [sxo'lio] → σκολειό [sko'ʎo])

- [fθ] → [ft] (φθόνος ['fθonos] → φτόνος ['ftonos])

- [fx] → [fk]

- [xθ] → [xt] (χθές ['xθes] → χτές ['xtes])

For fricatives where the second was /s/:

- [fs] → [ps] (ἔπαυσα ['epafsa] → ἔπαψα ['epapsa])

The disappearance of /n/ in word-final position, which had begun sporadically in Late Antiquity, became more widespread, excluding certain dialects such as South Italian and Cypriot. The nasals /m/ and /n/ also disappeared before voiceless fricatives, for example νύμφη ['nyɱfi] → νύφη ['nifi], ἄνθος ['an̪θos] → ἄθος ['aθos].[22]

A new set of voiced plosives [(m)b], [(n)d] and [(ŋ)ɡ] developed through voicing of voiceless plosives after nasals. There is some dispute as to when exactly this development took place but apparently it began during the Byzantine period. The graphemes μπ, ντ and γκ for /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ can already be found in transcriptions from neighboring languages in Byzantine sources, like in ντερβίσης [der'visis], from Turkish: derviş ('dervish'). On the other hand, some scholars contend that post-nasal voicing of voiceless plosives began already in the Koine, as interchanges with β, δ, and γ in this position are found in the papyri.[23] The prenasalized voiced spirants μβ, νδ and γγ were still plosives by this time, causing a merger between μβ/μπ, νδ/ντ and γγ/γκ, which would remain except within educated varieties, where spelling pronunciations did make for segments such as [ɱv, n̪ð, ŋɣ][24]

Grammar

Many decisive changes between Ancient and Modern Greek were completed by c. 1100 AD. There is a striking reduction of inflectional categories inherited from Indo-European, especially in the verbal system, and a complementary tendency of developing new analytical formations and periphrastic constructions.

In morphology, the inflectional paradigms of declension, conjugation and comparison were regularised through analogy. Thus, in nouns, the Ancient Greek third declension, which showed an unequal number of syllables in the different cases, was adjusted to the regular first and second declension by forming a new nominative form out of the oblique case forms: Ancient Greek ὁ πατήρ [ho patɛ́ːr] → Modern Greek ὁ πατέρας [o pa'teras], in analogy to the accusative form τὸν πατέρα [tom ba'tera]. Feminine nouns ending in -ις [-is] and -ας [-as] formed the nominative according to the accusative -ιδα [-iða] -αδα [-aða], as in ἐλπίς [elpís] → ἐλπίδα [elˈpiða] ('hope'), πατρίς [patrís] → πατρίδα [paˈtriða] ('homeland'), and in Ἑλλάς [hellás] → Ἑλλάδα [eˈlaða] ('Greece'). Only a few nouns remained unaffected by this simplification, such as τὸ φῶς [to fos] (both nominative and accusative), τοῦ φωτός [tu fo'tos] (genitive).

The Ancient Greek formation of the comparative of adjectives ending in -ων, -ιον, [-oːn, -ion] which was partly irregular, was gradually replaced by the formation using the more regular suffix -τερος, -τέρα (-τερη), -τερο(ν), [-teros, -tera (-teri), -tero(n)]: µείζων [méːzdoːn] → µειζότερος [mi'zoteros] ('the bigger').

The enclitic genitive forms of the first and second person personal pronoun, as well as the genitive forms of the third person demonstrative pronoun, developed into unstressed enclitic possessive pronouns that were attached to nouns: µου [mu], σου [su], του [tu], της [tis], µας [mas], σας [sas], των [ton].

Irregularities in verb inflection were also reduced through analogy. Thus, the contracted verbs ending in -άω [-aoː], -έω [-eoː] etc., which earlier showed a complex set of vowel alternations, readopted the endings of the regular forms: ἀγαπᾷ [aɡapâːi] → ἀγαπάει [aɣaˈpai] ('he loves'). The use of the past tense prefix, known as augment, was gradually limited to regular forms in which the augment was required to carry word stress. Reduplication in the verb stem, which was a feature of the old perfect forms, was gradually abandoned and only retained in antiquated forms. The small ancient Greek class of irregular verbs in -μι [-mi] disappeared in favour of regular forms ending in -ω [-oː]; χώννυμι [kʰóːnnymi] → χώνω ['xono] ('push'). The auxiliary εἰμί [eːmí] ('be'), originally part of the same class, adopted a new set of endings modelled on the passive of regular verbs, as in the following examples:

| Classical | Medieval | Regular passive ending | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | ||||||

| 1st person sing. | εἰμί | [eːmí] | εἶμαι | ['ime] | -μαι | [-me] |

| 2nd person sing. | εἶ | [êː] | εἶσαι | ['ise] | -σαι | [-se] |

| 3rd person sing. | ἐστίν | [estín] | ἔνι → ἔναι, εἶναι | ['eni → ˈene, ˈine] | -ται | [-te] |

| Imperfect | ||||||

| 1st person sing. | ἦν | [ɛ̂ː] | ἤμην | ['imin] | -μην | [-min] |

| 2nd person sing. | ἦσθα | [ɛ̂ːstʰa] | ἦσοι | ['isy] | -σοι | [-sy] |

| 3rd person sing. | ἦν | [ɛ̂ːn] | ἦτο | [ˈito] | -το | [-to] |

In most cases, the numerous stem variants that appeared in the Ancient Greek system of aspect inflection were reduced to only two basic stem forms, sometimes only one. Thus, in Ancient Greek the stem of the verb λαμβάνειν [lambáneːn] ('to take') appears in the variants λαμβ- [lamb-], λαβ- [lab-], ληψ- [lɛːps-], ληφ- [lɛːpʰ-] and λημ- [lɛːm-]. In Medieval Greek, it is reduced to the forms λαμβ- [lamb-] (imperfective or present system) and λαβ- [lav-] (perfective or aorist system).

One of the numerous forms that disappeared was the dative. It was replaced in the 10th century by the genitive and the prepositional construction of εἰς [is] ('in, to') + accusative. In addition, nearly all the participles and the imperative forms of the 3rd person were lost. The subjunctive was replaced by the construction of subordinate clauses with the conjunctions ὅτι [ˈoti] ('that') and ἵνα [ˈina] ('so that'). ἵνα first became ἱνά [iˈna] and was later shortened to να [na]. By the end of the Byzantine era, the construction θέλω να [ˈθelo na] ('I want that…') + subordinate clause developed into θενά [θeˈna]. Eventually, θενά became the Modern Greek future particle θα Medieval Greek: [θa], which replaced the old future forms. Ancient formations like the genitive absolute, the accusative and infinitive and nearly all common participle constructions were gradually substituted by the constructions of subordinate clauses and the newly emerged gerund.

The most noticeable grammatical change in comparison to ancient Greek is the almost complete loss of the infinitive, which has been replaced by subordinate clauses with the particle να. Possibly transmitted through Greek, this phenomenon can also be found in the adjacent languages and dialects of the Balkans. Bulgarian and Romanian, for example, are in many respects typologically similar to medieval and present day Greek, although genealogically they are not closely related.

Besides the particles να and θενά, the negation particle δέν [ðen] ('not') was derived from Ancient Greek: oὐδέν [uːdén] ('nothing').

Vocabulary, script, influence on other languages

Intralinguistic innovations

Lexicographic changes in Medieval Greek influenced by Christianity can be found for instance in words like ἄγγελος [ˈaɲɟelos] ('messenger') → heavenly messenger → angel) or ἀγάπη [aˈɣapi] 'love' → 'altruistic love', which is strictly differentiated from ἔρως [ˈeros], ('physical love'). In everyday usage, some old Greek stems were replaced, for example, the expression for "wine" where the word κρασίον [kraˈsion] ('mixture') replaced the old Greek οἶνος [oînos]. The word ὄψον [ˈopson] (meaning 'something you eat with bread') combined with the suffix -αριον [-arion], which was borrowed from the Latin -arium, became 'fish' (ὀψάριον [oˈpsarion]), which after apheresis, synizesis and the loss of final ν [n] became the new Greek ψάρι [ˈpsari] and eliminated the Old Greek ἰχθύς [ikʰtʰýs], which became an acrostic for Jesus Christ and a symbol for Christianity.

Loanwords from other languages

Especially at the beginning of the Byzantine Empire, Medieval Greek borrowed numerous words from Latin, among them mainly titles and other terms of the imperial court's life like Αὔγουστος [ˈavɣustos] ('Augustus'), πρίγκιψ [ˈpriɲɟips] (Latin: princeps, 'Prince'), μάγιστρος [ˈmaʝistros] (Latin: magister, 'Master'), κοιαίστωρ [cyˈestor] (Latin: quaestor, 'Quaestor'), ὀφφικιάλος [ofiˈcalos] (Latin: officialis, 'official'). In addition, Latin words from everyday life entered the Greek language, for example ὁσπίτιον [oˈspition] (Latin: hospitium, 'hostel', therefore "house", σπίτι [ˈspiti] in Modern Greek), σέλλα [ˈsela] ('saddle'), ταβέρνα [taˈverna] ('tavern'), κανδήλιον [kanˈdilion] (Latin: candela, 'candle'), φούρνος [ˈfurnos] (Latin: furnus, 'oven') and φλάσκα [ˈflaska] (Latin: flasco, 'wine bottle').

Other influences on Medieval Greek arose from contact with neighboring languages and the languages of Venetian, Frankish and Arab conquerors. Some of the loanwords from these languages have been permanently retained in Greek or in its dialects:

Script

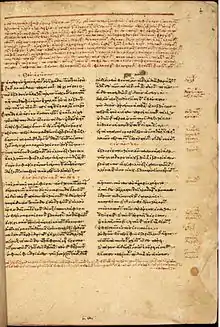

Middle Greek used the 24 letters of the Greek alphabet which, until the end of antiquity, were predominantly used as lapidary and majuscule letters and without a space between words and with diacritics.

Uncial and cursive script

The first Greek script, a cursive script, developed from quick carving into wax tablets with a slate pencil. This cursive script already showed descenders and ascenders, as well as combinations of letters.

In the third century, the Greek uncial developed under the influence of the Latin script because of the need to write on papyrus with a reed pen. In the Middle Ages, uncial became the main script for the Greek language.

A common feature of the medieval majuscule script like the uncial is an abundance of abbreviations (e.g. ΧϹ for "Christos") and ligatures. Several letters of the uncial (ϵ for Ε, Ϲ for Σ, Ѡ for Ω) were also used as majuscules especially in a sacral context. The lunate sigma was adopted in this form as "С" in the Cyrillic script.

The Greek uncial used the interpunct in order to separate sentences for the first time, but there were still no spaces between words.

Minuscule script

The Greek minuscule script, which probably emerged from the cursive writing in Syria, appears more and more frequently from the 9th century onwards. It is the first script that regularly uses accents and spiritus, which had already been developed in the 3rd century BC. This very fluent script, with ascenders and descenders and many possible combinations of letters, is the first to use gaps between words. The last forms which developed in the 12th century were Iota subscript and word-final sigma (ς). The type for Greek majuscules and minuscules that was developed in the 17th century by a printer from the Antwerp printing dynasty, Wetstein, eventually became the norm in modern Greek printing.

Influence on other languages

As the language of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Middle Greek has, especially with the conversion of the Slavs by the brothers Cyril and Methodius, found entrance into the Slavic languages via the religious sector, in particular to the Old Church Slavonic and over its subsequent varieties, the different Church Slavonic manuscripts, also into the language of the countries with an Orthodox population, thus primarily into Bulgarian, Russian, Ukrainian and Serbian, as well as on Romanian, sometimes partly through South Slavic intermediates. For this reason, Greek loanwords and neologisms in these languages often correspond to the Byzantine phonology, while they found their way into the languages of Western Europe over Latin mediation in the sound shape of the classical Greek (cf. German: Automobil vs. Russian: автомобиль avtomobil, and the differences in Serbo-Croatian).

Some words in Germanic languages, mainly from the religious context, have also been borrowed from Medieval Greek and have found their way into languages like German through the Gothic language. This includes the word the German word for Pentecost, Pfingsten (from πεντηκοστή‚ 'the fiftieth [day after Easter]').

Byzantine research played an important role in the Greek State, which was refounded in 1832, as the young nation tried to restore its cultural identity through antique and orthodox-medieval traditions. Spyridon Lambros (1851–1919), later Prime Minister of Greece, founded Greek Byzantinology, which was continued by his and Krumbacher's students.

Sample Medieval Greek texts

The following texts clearly illustrate the case of diglossia in Byzantine Greek, as they date from roughly the same time but show marked differences in terms of grammar and lexicon, and likely in phonology as well. The first selection is an example of high literary classicizing historiography, while the second is a vernacular poem which is more compromising to ordinary speech.

Sample 1 – Anna Komnena

The first excerpt is from the Alexiad of Anna Komnena, recounting the invasion by Bohemond I of Antioch, son of Robert Guiscard, in 1107. The writer employs much ancient vocabulary, influenced by Herodotean Ionic, though post-classical terminology is also used (e.g. δούξ, from Latin: dux). Anna has a strong command of classical morphology and syntax, but again there are occasional 'errors' reflecting interference from the popular language, such as the use of εἰς + accusative instead of classical ἐν + dative to mean 'in'. As seen in the phonetic transcription, although most major sound changes resulting in the Modern Greek system (including the merger of υ/οι /y/ with /i/) are assumed complete by this period, learned speech likely resisted the loss of final ν, aphaeresis and synizesis.[25]

Ὁ δὲ βασιλεὺς, ἔτι εἰς τὴν βασιλεύουσαν ἐνδιατρίβων, μεμαθηκὼς διὰ γραφῶν τοῦ δουκὸς Δυρραχίου τὴν τοῦ Βαϊμούντου διαπεραίωσιν ἐπετάχυνε τὴν ἐξέλευσιν. ἀνύστακτος γὰρ ὤν ὁ δοὺξ Δυρραχίου, μὴ διδοὺς τὸ παράπαν ὕπνον τοῖς ὀφθαλμοῖς, ὁπηνίκα διέγνω διαπλωσάμενον τὸν Βαϊμούντον παρὰ τὴν τοῦ Ἰλλυρικοῦ πεδιάδα καὶ τῆς νηὸς ἀποβεβηκότα καὶ αὐτόθι που πηξάμενον χάρακα, Σκύθην μεταπεψάμενος ὑπόπτερον δή, τὸ τοῦ λόγου, πρὸς τὸν αὐτοκράτορα τὴν τούτου διαπεραίωσιν ἐδήλου.

[o ðe vasiˈlefs, ˈeti is tim vasiˈlevusan enðjaˈtrivon, memaθiˈkos ðja ɣraˈfon tu ðuˈkos ðiraˈçiu tin du vaiˈmundu ðjapeˈreosin epeˈtaçine tin eˈkselefsin. aˈnistaktos ɣar on o ðuks ðiraˈçiu, mi ðiˈðus to paˈrapan ˈipnon tis ofθalˈmis, opiˈnika ˈðjeɣno ðjaploˈsamenon tom vaiˈmundon para tin du iliriˈku peˈðjaða ce tiz niˈos apoveviˈkota ce afˈtoθi pu piˈksamenon ˈxaraka, ˈsciθin metapemˈpsamenos iˈpopteron ði, to tu ˈloɣu, pros ton aftoˈkratora tin ˈdutu ðjapeˈreosin eˈðilu.]

'When the emperor, who was still in the imperial city, learned of Bohemond's crossing from the letters of the duke (military commander) of Dyrráchion, he hastened his departure. For the duke had been vigilant, having altogether denied sleep to his eyes, and at the moment when he learned that Bohemond had sailed over beside the plain of Illyricum, disembarked, and set up camp thereabouts, he sent for a Scythian with "wings", as the saying goes, and informed the emperor of the man's crossing.'

Sample 2 – Digenes Akritas

The second excerpt is from the epic of Digenes Akritas (manuscript E), possibly dating originally to the 12th century. This text is one of the earliest examples of Byzantine folk literature, and includes many features in line with developments in the demotic language. The poetic metre adheres to the fully developed Greek 15-syllable political verse. Features of popular speech like synezisis, elision and apheresis are regular, as is recognized in the transcription despite the conservative orthography. Also seen is the simplification of διὰ to modern γιὰ. In morphology, note the use of modern possessive pronouns, the concurrence of classical -ουσι(ν)/-ασι(ν) and modern -ουν/-αν 3rd person plural endings, the lack of reduplication in perfect passive participles and the addition of ν to the neuter adjective in γλυκύν. In other parts of the poem, the dative case has been almost completely replaced with the genitive and accusative for indirect objects.[26]

Καὶ ὡς εἴδασιν τὰ ἀδέλφια της τὴν κόρην μαραμένην,

ἀντάμα οἱ πέντε ἐστέναξαν, τοιοῦτον λόγον εἶπαν:

'Ἐγείρου, ἠ βεργόλικος, γλυκύν μας τὸ ἀδέλφιν˙

ἐμεῖς γὰρ ἐκρατοῦμαν σε ὡς γιὰ ἀποθαμένην

καὶ ἐσὲν ὁ Θεὸς ἐφύλαξεν διὰ τὰ ὡραῖα σου κάλλη.

Πολέμους οὐ φοβούμεθα διὰ τὴν σὴν ἀγάπην.'[c os ˈiðasin t aˈðelfja tis tiŋ ˈɡorin maraˈmeni(n) anˈdama i ˈpende ˈstenaksan, tiˈuto(n) ˈloɣon ˈipa(n): eˈjiru, i verˈɣolikos, ɣliˈci(m) mas to aˈðelfi(n); eˈmis ɣar ekraˈtuman se os ja apoθaˈmeni(n) c eˈsen o ˈθjos eˈfilakse(n) (ð)ja t oˈrea su ˈkali. poˈlemus u foˈvumeθa ðiˈa ti ˈsin aˈɣapi(n)]

'And when her brothers saw the girl withered, the five groaned together, and spoke as follows: "Arise, lissom one, our sweet sister; we had you for dead, but you were protected by God for your beautiful looks. Through our love for you, we fear no battles.'

Research

In the Byzantine Empire, Ancient and Medieval Greek texts were copied repeatedly; studying these texts was part of Byzantine education. Several collections of transcriptions tried to record the entire body of Greek literature since antiquity. As there had already been extensive exchange with Italian academics since the 14th century, many scholars and a large number of manuscripts found their way to Italy during the decline of the Eastern Roman Empire. Renaissance Italian and Greek humanists set up important collections in Rome, Florence and Venice. The conveyance of Greek by Greek contemporaries also brought about the itacistic tradition of Greek studies in Italy.

The Greek tradition was also taken to Western and Middle Europe in the 16th century by scholars who had studied at Italian universities. It included Byzantine works that mainly had classical Philology, History and Theology but not Medieval Greek language and literature as their objects of research. Hieronymus Wolf (1516–1580) is said to be the "father" of German Byzantism. In France, the first prominent Byzantist was Charles du Fresne (1610–1688). As the Enlightenment saw in Byzantium mainly the decadent, perishing culture of the last days of the empire, the interest in Byzantine research decreased considerably in the 18th century.

It was not until the 19th century that the publication of and research on Medieval Greek sources began to increase rapidly, which was particularly inspired by Philhellenism. Furthermore, the first texts in vernacular Greek were edited. The branch of Byzantinology gradually split from Classical Philology and became an independent field of research. The Bavarian scholar Karl Krumbacher (1856–1909) carried out research in the newly founded state of Greece, and is considered the founder of Medieval and Modern Greek Philology. From 1897 onwards, he held the academic chair of Medieval and Modern Greek at the University of Munich. In the same century Russian Byzantinology evolved from a former connection between the Orthodox Church and the Byzantine Empire.

Byzantinology also plays a large role in the other countries on the Balkan Peninsula, as Byzantine sources are often very important for the history of each individual people. There is, therefore, a long tradition of research, for example in countries like Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary. Further centres of Byzantinology can be found in the United States, Great Britain, France and Italy. Today the two most important centres of Byzantinology in German speaking countries are the Institute for Byzantine Studies, Byzantine Art History and the Institute of Modern Greek Language and Literature at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, and the Institute of Byzantine Studies and of Modern Greek Language and Literature at the University of Vienna. The International Byzantine Association is the umbrella organization for Byzantine Studies and has its head office in Paris.

See also

References

- Peter Mackridge, "A language in the image of the nation: Modern Greek and some parallel cases", 2009.

- The separate code "gkm" was proposed for inclusion in ISO 639-3 in 2006. The request is still pending. ("Change Request Documentation: 2006-084". sil.org. Retrieved 2018-05-19.)

- Dawkins, R.M. 1916. Modern Greek in Asia Minor. A study of dialect of Silly, Cappadocia and Pharasa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrogorsky 1969, "The Struggle for Existence (610-711)", p. 106.

- «In that wretched city the reign of Romans lasted for 1143 years» (George Sphrantzes, Chronicle, ια΄, c.1460)

- Mango 1980, p. 23.

- Lombard 2003, p. 93: "Here too Coptic and Greek were progressively replaced by Arabic, although less swiftly. Some dates enable us to trace the history of this process. The conquest of Egypt took place from 639 to 641, and the first bilingual papyrus (Greek and Arabic) is dated 693 and the last 719, while the last papyrus written entirely in Greek is dated 780 and the first one entirely in Arabic 709."

- Toufexis 2008, pp. 203–217.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1889). "ἀντίστοιχος". An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon. Oxford University Press. p. 81.

- "Antistœchal". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- Browning, Robert (1983). Medieval and Modern Greek. London: Hutchinson University Library. pp. 56–57.

- F. Lauritzen, Michael the Grammarian's irony about Hypsilon. A step towards reconstructing Byzantine pronunciation. Byzantinoslavica, 67 (2009)

- Machardse, Neli A. (1980). "Zur Lautung der griechische Sprache in de byzantinischen Zeit". Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik (29): 144–150.

- C.f. dissimilation of voiceless obstruents below.

- Horrocks, Geoffrey C. (2010). Greek: A history of the language and its speakers (2nd ed.). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 276–277.

- See Appendix III in Maas and C.A. Trypanis, Paul (1963). Sancti Romani melodi cantica: Cantica dubia. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Horrocks (2010: 175-176)

- Horrocks (2010: Ch. 6) for a summary of these previous developments in the Koine.

- Horrocks (2010: 281-282)

- See Horrocks (2010: 405.)

- Horrocks (2010: 281)

- Horrocks (2010: 274-275)

- Horrocks (2010: 111, 170)

- Horrocks (2010: 275-276)

- Horrocks (2010: 238-241)

- Horrocks (2010: 333-337)

Sources

- Horrocks, Geoffrey (2010). Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lombard, Maurice (2003). The Golden Age of Islam. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 1-55876-322-8.

- Mango, Cyril A. (1980). Byzantium: The Empire of New Rome. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-16768-9.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1969). History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1198-4.

- Toufexis, Notis (2008). "Diglossia and register variation in Medieval Greek". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 32 (2): 203–217. doi:10.1179/174962508X322687. S2CID 162128578. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

Further reading

- Andriotis, Νicholas P. (1995). History of the Greek Language. Thessalonica, Greece: Institute of Neo-Hellenic Studies.

- Browning, Robert (1983). Medieval and Modern Greek. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29978-0.

- Horrocks, Geoffrey (2010). Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-3415-6.

- Tonnet, Henri (2003). Histoire du grec moderne: la formation d'une langue. L'Asiathèque Langues du monde. ISBN 2-911053-90-7.

- Holton, David; Horrocks, Geoffrey; Janssen, Marjolijne; Lendari, Tina; Manolessou, Io; Toufexis, Notis (2020). The Cambridge Grammar of Medieval and Early Modern Greek. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316632840. ISBN 9781139026888. S2CID 222381614.