Albania in the Middle Ages

When the Roman Empire divided into east and west in 395, the territories of modern Albania became a part of the Byzantine Empire. At the end of the 12th century, the Principality of Arbanon was formed which lasted until mid 13th century, after its dissolution it was followed with the creation of the Albanian Kingdom after an alliance between the Albanian noblemen and Angevin dynasty. After a war against the Byzantine empire led the kingdom occasionally decrease in size until the Angevins eventually lost their rule in Albania and led the territory ruled by several different Albanian chieftains until the mid 14th century which for a short period of time were conquered by the short-lived empire of Serbia. After its fall in 1355 several chieftains regained their rule and significantly expanded until the arrival of the Ottomans after the Battle of Savra.

| History of Albania |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

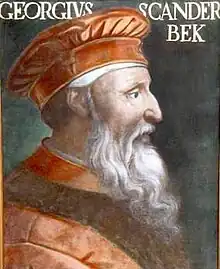

After the Battle of Savra in 1385 most of local chieftains became Ottoman vassals. In 1415–1417 most of the central and southern Albania was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire and its newly established Sanjak of Albania. In 1432-36 local Albanian chieftains dissatisfied with losing their pre-Ottoman privileges organized a revolt in southern Albania. The revolt was suppressed until another revolt was organized by Skanderbeg in 1443, after the Ottoman defeat in the Battle of Niš, during the Crusade of Varna. In 1444, Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg was proclaimed as the leader of the regional Albanian chieftains and nobles united against the Ottoman Empire in the League of Lezhë disestablished in 1479. Skanderbeg's rebellion against the Ottoman Empire lasted for 25 years. Despite his military valor he was not able to do more than to hold his own possessions within the very small area in the North Albania where almost all his victories against the Ottomans took place. By 1479 the Ottomans captured all Venetian possessions, except Durazzo which they captured in 1501. Until 1913 the territory of Albania would remain part of the Ottoman Empire.

Komani-Kruja culture

The Komani-Kruja culture is an archaeological culture attested from late antiquity to the Middle Ages in central and northern Albania, southern Montenegro and similar sites in the western parts of North Macedonia. It consists of settlements usually built below hillforts along the Lezhë (Praevalitana)-Dardania and Via Egnatia road networks which connected the Adriatic coastline with the central Balkan Roman provinces. Its type site is Komani and its fort on the nearby Dalmace hill in the Drin river valley. Kruja and Lezha represent significant sites of the culture. The population of Komani-Kruja represents a local, western Balkan people which was linked to the Roman Justinianic military system of forts. The development of Komani-Kruja is significant for the study of the transition between the classical antiquity population of Albania to the medieval Albanians who were attested in historical records in the 11th century.

Research greatly expanded after 2009 and the first survey of Komani's topography was produced in 2014. Until then, except for the area of the cemetery the size of the settlement and its extension remained unknown. In 2014, it was revealed that Komani occupied an area of more than 40 ha, a much larger territory than originally thought. Its oldest settlement phase dates to the Hellenistic era.[1] Proper development began in the late antiquity and continued well into the Middle Ages (13th-14th centuries). It indicates that Komani was a late Roman fort and an important trading node in the networks of Praevalitana and Dardania. Participation in trade networks of the eastern Mediterranean via sea routes seems to have been very limited even in nearby coastal territory in this era.[2] In the Avar-Slavic raids, communities from present-day northern Albania and nearby areas clustered around hill sites for better protection as is the case of other areas like Lezha and Sarda. During the 7th century as Byzantine authority was reestablished after the Avar-Slavic raids and the prosperity of the settlements increased, Komani saw increase in population and a new elite began to take shape. Increase in population and wealth was marked by the establishment of new settlements and new churches in their vicinity. Komani formed a local network with Lezha and Kruja and in turn this network was integrated in the wider Byzantine Mediterranean world, maintained contacts with the northern Balkans and engaged in long-distance trade.[3]

History

Byzantine Empire

After the region fell to the Romans in 168 BC it became part of Epirus Nova that was in turn part of the Roman province of Macedonia. Later it was part of provinces of the Byzantine empire called themes.

When the Roman Empire was divided into East and West in 395, the territories of modern Albania became part of the Byzantine Empire. Beginning in the first decades of Byzantine rule (until 461), the region suffered devastating raids by Visigoths, Huns, and Ostrogoths. In the 6th and 7th centuries, the region experienced an influx of Slavs.

The Albanians appear in medieval Byzantine chronicles in the 11th century, as Albanoi and Arbanitai, and in medieval Latin sources as Albanenses and Arbanenses,[4][5] gradually entering in other European languages, in which other similar derivative names emerged.[6] At this point, they are already fully Christianized. In later Byzantine usage, the terms Arbanitai and Albanoi, with a range of variants, were used interchangeably, while sometimes the same groups were also called by the classicising name Illyrians.[7][8][9]

The Albanians, during the Middle Ages, referred to their country as Arbëria (Gheg Albanian: Arbënia) and called themselves Arbëreshë (Gheg Albanian: Arbëneshë).[10][11]

Barbarian Invasions

In the first decades under Byzantine rule (until 461), Epirus nova suffered the devastation of raids by Visigoths, Huns, and Ostrogoths. Not long after these barbarian invaders swept through the Balkans, the Slavs appeared. Between the 6th and 8th centuries they settled in Roman territories. In the 4th century, barbarian tribes began to prey upon the Roman Empire. The Germanic Goths and Asiatic Huns were the first to arrive, invading in mid-century; the Avars attacked in AD. 570; and Slavs invaded in the 6th and 7th century. About fifty years later, the Bulgars conquered much of the Balkan Peninsula and extended their domain to the lowlands of what is now central Albania. In general, the invaders destroyed or weakened Roman and Byzantine cultural centers in the lands that would become Albania.[12]

Bulgarian Empire

In the mid-9th century most of eastern Albania became part of the First Bulgarian Empire, during the reign of Khan Presian.[13] The area, known as Kutmichevitsa, became an important Bulgarian cultural center in the 10th century with many thriving towns such as Devol, Glavinitsa (Ballsh) and Belgrad (Berat). Coastal towns such as Durrës remained in the hands of the Byzantines for most of that period. When the Byzantines managed to conquer the Bulgarian Empire in 1018–19, the fortresses in eastern Albania were some of the last Bulgarian strongholds to be submitted by the Byzantines. Durrës was one a centre of a major Bulgarian uprising in 1040–41 following the discontent of the Bulgarian population by the heavy taxes levied by the Byzantines. Soon the rebellion encompassed the whole of Albania, but it was quelled in 1041, after which Albania again came under Byzantine rule. In 1072 another uprising broke out under Georgi Voiteh but it was also crushed.

Later the region was recovered by the Second Bulgarian Empire. The last Bulgarian Emperor to govern the whole territory was Ivan Asen II (1218–1241) but after his successors the Bulgarian rule diminished.

Serbian Empire

The Serbs controlled parts of what is now northern and eastern Albania toward the end of the 12th century. In 1204, after Western crusaders sacked Constantinople, Venice won nominal control over Albania and the Epirus region of northern Greece and took possession of Durrës. A prince from the overthrown Byzantine ruling family, Michael Comnenus, made alliances with Albanian chiefs and drove the Venetians from lands that now make up southern Albania and northern Greece, and in 1204 he set up an independent principality, the Despotate of Epirus, with Ioannina in northwest Greece) as its capital. In 1272 the king of Naples, Charles I of Anjou, occupied Durrës and formed an Albanian kingdom that would last for a century. Internal power struggles further weakened the Byzantine Empire in the 14th century, enabling Serbian most powerful medieval ruler, Stefan Dusan, to establish a short-lived empire that included all of Albania except Durrës.[12]

Principality of Arbanon

.png.webp)

Arbanon was an autonomous principality that existed between the late 12th century and the 1250s. Throughout its existence, the principality was an autonomous dependency of its neighbouring powers, first Byzantium and, after the Fourth Crusade, Epirus, while it also maintained close relations with Serbia.[14] Arbanon extended over the modern districts of central Albania, with the capital at Kruja,[15] and it did not have direct access to the sea.[16] Progon was the first ruler, believed to have ruled in ca. 1190. He was succeeded by his sons Gjin (r. c. 1200–08) and Dimitri (r. 1208–16). After this dynasty, the principality came under Greek lord Gregory Kamonas[17] and then his son-in-law Golem.[18] Dimitri's widow, Serbian princess Komnena Nemanjić, had inherited the rule[19] and remarried Kamonas.[17] Arbanon declined after a rebellion against Nicaea in favour of Epirus in 1257–58.

Kingdom of Albania

After the fall of the Principality of Arber in its territories and in territories captured by the Despotate of Epiros was created the Kingdom of Albania, which was established by Charles of Anjou. He took the title of King of Albania in February, 1272. The kingdom extended from Durazzo (modern Durrës) south along the coast to Cape Linguetta, with vaguely defined borders in the interior. A Byzantine counter-offensive soon ensued, which drove the Angevins out of the interior by 1281. The Sicilian Vespers further weakened the position of Charles, and the Kingdom was soon reduced by the Epirotes to a small area around Durrës. The Angevins held out here, however, until 1368, when the city was captured by Karl Thopia.

After the fall of the Principality of Arber in territories captured by the Despotate of Epirus, the Kingdom of Albania was established by Charles of Anjou. He took the title of King of Albania in February 1272. The kingdom extended from the region of Durrës (then known as Dyrrhachium) south along the coast to Butrint. After the failure of the Eighth Crusade, Charles of Anjou returned his attention to Albania. He began contacting local Albanian leaders through local catholic clergy. Two local Catholic priests, namely John from Durrës and Nicola from Arbanon, acted as negotiators between Charles of Anjou and the local noblemen. During 1271 they made several trips between Albania and Italy eventually succeeding in their mission.[20]

On 21 February 1272, a delegation of Albanian noblemen and citizens from Durrës made their way to Charles' court. Charles signed a treaty with them and was proclaimed King of Albania "by common consent of the bishops, counts, barons, soldiers and citizens" promising to protect them and to honor the privileges they had from Byzantine Empire.[21] The treaty declared the union between the Kingdom of Albania (Latin: Regnum Albanie) with the Kingdom of Sicily under King Charles of Anjou (Carolus I, dei gratia rex Siciliae et Albaniae).[20] He appointed Gazzo Chinardo as his Vicar-General and hoped to take up his expedition against Constantinople again. Throughout 1272 and 1273 he sent huge provisions to the towns of Durrës and Vlorë. This alarmed the Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos, who began sending letters to local Albanian nobles, trying to convince them to stop their support for Charles of Anjou and to switch sides. However, the Albanian nobles placed their trust on Charles, who praised them for their loyalty. But Charles of Anjou imposed a military rule on Kingdom of Albania.

Throughout its existence the Kingdom saw armed conflict with the Byzantine empire. By 1282 the Angevins were weakened by the Sicilian Vespers but held control of the nominal parts of Albania and even recaptured some and held out until 1368 when the kingdom's territory was reduced to a small area in Durrës. Even before the city of Durrës was captured, it was landlocked by Karl Thopia's principality. Declaring himself as Angevin descendant, with the capture of Durrës in 1368 Karl Thopia created the Princedom of Albania. During its existence Catholicism saw rapid spread among the population which affected the society as well as the architecture of the Kingdom.A Western type of feudalism was introduced and it replaced the Byzantine Pronoia.

Albanian principalities

.png.webp)

The 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century was the period in which sovereign principalities were created in Albania under Albanian noblemen. Those principalities were created between the fall of the Serbian Empire and the Ottoman invasion of Albania.

In the summer of 1358, Nikephoros II Orsini, the last despot of Epirus of the Orsini dynasty, fought against the Albanian chieftains in Acheloos, Acarnania. The Albanian chieftains won the war and they managed to create two new states in the southern territories of the Despotate of Epirus. Because a number of Albanian lords actively supported the successful Serbian campaign in Thessaly and Epirus, the Serbian Tsar granted them specific regions and offered them the Byzantine title of despotes in order to secure their loyalty.

The two Albanian lead states were: the first with its capital in Arta was under the Albanian nobleman Pjetër Losha, and the second, centered in Angelokastron, was ruled by Gjin Bua Shpata. After the death of Pjetër Losha in 1374, the Albanian Despotate of Arta and Angelocastron were united under the rule of Despot Gjin Bua Shpata. The territory of this despotate was from the Corinth Gulf to Acheron River in the North, neighboring with the Principality of Gjon Zenevisi, another state created in the area of the Despotate of Epirus.

From 1335 until 1432 four main principalities were created in Albania. The first of them was the Muzakaj Principality of Berat, created in 1335 in Berat and Myzeqe. The most powerful was the Princedom of Albania, formed after the disestablishment of Kingdom of Albania, by Karl Thopia. The principality changed hands between the Thopia dynasty and the Balsha dynasty, until 1392, when it was occupied by the Ottoman Empire. When Skanderbeg liberated Kruja and reorganised the Principality of Kastrioti, the descendant of Gjergj Thopia, Andrea II Thopia, managed to regain control of the Princedom. Finally, it was united with other Albanian Principalities forming the League of Lezhë in 1444.

Another principality was the Principality of Kastrioti, created by Gjon Kastrioti, and later captured by the Ottoman Empire. Finally, it was liberated by the national hero of Albania, Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg. The Principality of Dukagjini extended from the Malësia region to Prishtina in Kosovo.[22]

League of Lezhë

Under pressure by the Ottoman Empire, the Albanian Principalities were united into a confederation, created in the Assembly of Lezhë on 2 March 1444. The league was led by Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, and by Lekë Dukagjini following his death. Skanderbeg organized a meeting of Albanian nobles: the Arianiti, Dukagjini, Spani, Thopias, Muzakas, and the leaders of the free Albanian principalities from high mountains, in the town of Lezhë, where the nobles agreed to fight together for mutual gain against the common Turkish enemy. They voted Skanderbeg as their suzerain chief. The League of Lezhë was a confederation and each principality kept its sovereignty.

In the light of the modern geopolitical science, the League of Lezhë represented an attempt to form a state union. In fact, this was a federation of independent rulers who undertook the duty to follow a common foreign policy, to jointly defend their independence and recruit their allied armed forces. Naturally, it required a collective budget for covering the military expenditures; each family contributed their mite to the common funds of the League. At the same time, each clan kept its possessions and autonomy, to solve internal problems within its own estate. The formation and functioning of the League, of which Gjergj Kastrioti was the supreme feudal lord, was the most significant attempt to build up an all-Albanian resistance against the Ottoman occupation and, simultaneously, an effort to create, for the span of its short-lived functioning, of some sort of a unified Albanian state. Under Skanderbeg's command, the Albanian forces marched east, capturing the cities of Dibra and Ohrid. For 25 years, from 1443 – 1468, Skanderbeg's 10,000 men army marched through Ottoman territory, winning victory after victory against the consistently larger and better supplied Ottoman forces. Threatened by Ottoman advances in their homeland, Hungary, and later Naples and Venice, their former enemies, provided the financial backbone and support for Skanderbeg's army.

On 14 May 1450, an Ottoman army, larger than any previous force encountered by Skanderbeg or his men, stormed and overwhelmed the castle of the city of Krujë. This city was particularly symbolic to Skanderbeg as he had been previously appointed suba of Krujë in 1438 by the Ottomans. The fighting lasted four months, with an Albanian loss of over 1,000 men and over 20,000 for the Ottomans. The Ottoman forces were unable to capture the city and had no choice but to retreat before winter set in. In June 1446, Mehmed II, known as "the conqueror", led an army of 150,000 soldiers back to Krujë, but failed to capture the castle. Skanderbeg's death in 1468 did not end the struggle for independence, and fighting continued until 1481, under Lekë Dukagjini, when Albanian lands were finally forced to succumb to the Ottoman forces.

Medieval culture

In the latter part of the Middle Ages, Albanian urban society reached a high point of development. Foreign commerce flourished to such an extent that leading Albanian merchants had their own agencies in Venice, Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik, Croatia), and Thessalonica (now Thessaloniki, Greece). The prosperity of the cities also stimulated the development of education and the arts. Albanian, however, was not the language used in schools, churches, and official government transactions. Instead, Greek and Latin, which had the powerful support of the state and the church, were the official languages of culture and literature. The new administrative system of the themes, or military provinces created by the Byzantine Empire, contributed to the eventual rise of feudalism in Albania, as peasant soldiers who served military lords became serfs on their landed estates. Among the leading families of the Albanian feudal nobility were the Thopia, Shpata, Muzaka, Arianiti, Dukagjini and Kastrioti. The first three of these rose to become rulers of principalities that were practically independent of Byzantium.

References

- Nallbani 2017, p. 320.

- Curta 2021, p. 79.

- Nallbani 2017, p. 325.

- Malcolm, Noel. "Kosovo, a short history". London: Macmillan, 1998, p.29.

- Robert Elsie (2010), Historical Dictionary of Albania, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, vol. 75 (2 ed.), Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0810861886

- Lloshi, Xhevat (1999). "Albanian", p. 277.

- Mazaris 1975, pp. 76–79.

- N. Gregoras (ed. Bonn) V, 6; XI, 6.

- Finlay 1851, p. 37.

- Demiraj, Bardhyl (2010), pp. 534.

- Kamusella, Tomasz (2009). The politics of language and nationalism in modern Central Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 241.

- Zickel, Raymond; Iwaskiw, Walter R., eds. (1994). ""The Barbarian Invasions and the Middle Ages," Albania: A Country Study". countrystudies.us/albania/index.htm. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- Andreev, Yordan (1996). The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars (Balgarskite hanove i tsare, Българските ханове и царе). Abagar. p. 70. ISBN 954-427-216-X.

- Ducellier 1999, pp. 780–781, 786

- Frashëri 1964, p. 43.

- Ducellier 1999, p. 780.

- Ducellier 1999, p. 786.

- Nicol 1986, p. 161.

- Nicol 1957, p. 48.

- Prifti, Skënder (5 September 2023). Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime (in Albanian). Albania. p. 207. ISBN 978-99927-1-622-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nicol, Donald M. (1 January 1984). The Despotate of Epiros 1267-1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521261906.

- Sellers, Mortimer (2010). The Rule of Law in Comparative Perspective. Springer. p. 207. ISBN 978-90-481-3748-0. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011.

Sources

- Fine, John V. A, Jr. (1991). The early Medieval Balkans; A critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ducellier, Alain (1999), "Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria", in Abulafia, David (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume V: c. 1198-c. 1300, Cambridge University Press, pp. 779–795, ISBN 0-521-36289-X

- Hill, Stephen (1992), "Byzantium and the Emergence of Albania", Warwick Studies in the European Humanities: 40–57, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-22050-2_4, ISBN 978-1-349-22052-6

- Ducellier, Alain (1981), La Façade maritime de l'Albanie au Moyen Age : Durazzo et Valona du XIe au XVe siècle, Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan studies, OCLC 492625425

- Galaty, Michael; Lafe, Ols; Lee, Wayne; Tafilica, Zamir (2013). Light and Shadow: Isolation and Interaction in the Shala Valley of Northern Albania. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. ISBN 978-1931745710.

- Finlay, George (1851). The History of Greece: From Its Conquest by the Crusaders to Its Conquest by the Turks, and of the Empire of Trebizond: 1204–1461. London: Blackwood.

- Frashëri, Kristo (1964). The history of Albania: a brief survey. Tirana. OCLC 230172517.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nallbani, Etleva (2017). "Early Medieval North Albania: New Discoveries, Remodeling Connections: The Case of Medieval Komani". In Gelichi, Sauro; Negrelli, Claudio (eds.). Adriatico altomedievale (VI-XI secolo) Scambi, porti, produzioni (PDF). Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia. ISBN 978-88-6969-115-7.

- Nicol, Donald McGillivray (1957). The Despotate of Epiros. Oxford: Blackwell & Mott, Limited.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1986). Studies in Late Byzantine History and Prosopography. London: Variorum Reprints. ISBN 978-0-86078-190-5.

- Curta, Florin (2021). The Long Sixth Century in Eastern Europe. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004456983.

External links

- Library of Congress Country Study of Albania

- Books about Albania and the Albanian people (scribd.com) Reference of books (and some journal articles) about Albania and the Albanian people; their history, language, origin, culture, literature, etc. Public domain books, fully accessible online.