Small and medium-sized enterprises

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) or small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) are businesses whose personnel and revenue numbers fall below certain limits. The abbreviation "SME" is used by international organizations such as the World Bank, the European Union, the United Nations, and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

In any given national economy, SMEs sometimes outnumber large companies by a wide margin and also employ many more people.[1][2] For example, Australian SMEs makeup 98% of all Australian businesses, produce one-third of the total GDP (gross domestic product) and employ 4.7 million people. In Chile, in the commercial year 2014, 98.5% of the firms were classified as SMEs.[3] In Tunisia, the self-employed workers alone account for about 28% of the total non-farm employment, and firms with fewer than 100 employees account for about 62% of total employment.[4] The United States' SMEs generate half of all U.S. jobs, but only 40% of GDP.[5]

Developing countries tend to have a larger share of small and medium-sized enterprises.[6][2] SMEs are also responsible for driving innovation and competition in many economic sectors.[7] Although they create more new jobs than large firms, SMEs also suffer the majority of job destruction/contraction.[8]

Overview

SMEs are important for economic and social reasons, given the sector's role in employment. Due to their sizes, SMEs are heavily influenced by their Chief Executive Officer, a.k.a. CEOs. The CEOs of SMEs are often the founders, owners, and managers of the SMEs. The duties of the CEO in a SME mirror those of the CEO of a large company: the CEO needs to strategically allocate their time, energy, and assets to direct the SMEs. Typically, the CEO is the strategist, champion and leader for developing the SME or the prime reason for the business failing.

At the employee level, Petrakis and Kostis (2012) explore the role of interpersonal trust and knowledge in the number of small and medium enterprises. They conclude that knowledge positively affects the number of SMEs, which in turn positively affects interpersonal trust. Note that the empirical results indicate that interpersonal trust does not affect the number of SMEs. Therefore, although knowledge development can reinforce SMEs, trust becomes widespread in a society when the number of SMEs is greater.[9]

Legal boundary on SMEs around the world

Multilateral organizations have been criticized for using one measure for all.[10][11] The legal boundary of SMEs around the world vary, and below is a list of the upper limits of SMEs in some countries.

Africa

%252C_Southern_Africa.png.webp)

African small businesses frequently struggle to get the cash they require to thrive. According to the SME Finance Forum, the formal financing gap for African SMEs averaged 17% of GDP across the 43 countries assessed in 2017.[13][14]

According to the World Bank, women own 58% of all MSMEs in Africa.[13][15][16]

The European Investment Bank's Banking in Africa survey, 2021 suggests that most of the responding banks had a non-performing loan (NPL) ratio of at least 5%. NPLs account for at least 10% of the SME portfolio in approximately one-third of African banks. Furthermore, 50% of the banks had at least 5% of their SME portfolio under the moratorium, and 40% had at least 5% of SME loans under some type of restructuring.[13]

Egypt

Most of Egypt's businesses are small-sized, with 97 percent employing fewer than 10 workers, according to census data released by state-run statistics body CAPMAS (Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics).

Medium-sized enterprises with 10 to 50 employees account for around 2.7 percent of total businesses. However, big businesses with over 50 employees account for 0.4 percent of all enterprises nationwide.

The data is part of Egypt's 2012/13 economic census on establishments ranging from small stalls to big enterprises. Economic activity outside the establishments – like street vendors and farmers, for example – were excluded from the census.

_respondents_in_East_Africa.png.webp)

The results show that Egypt is greatly lacking in medium-sized businesses.

Seventy percent of the country's 24 million businesses have only one or two employees. But less than 0.1 percent – only 784 businesses – employ between 45 and 49 people.

Kenya

In Kenya, the term changed to MSME, which stands for "micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises".

For micro-enterprises, the minimum number of employees is up to 10 employees. For small enterprises, it is from 10 to 50. For medium enterprises, it is from 50 to 100.

Nigeria

The Central Bank of Nigeria defines small and medium enterprises in Nigeria according to asset base and a number of staff employed. The criteria are an asset base that is between ₦5 million ($15,400) to ₦500 million ($1,538,000), and a staff strength that is between 11 and 100 employees.[2][17]

Somalia

In Somalia, the term is SME (for "small, medium, and micro enterprises"); elsewhere in Africa, MSME stands for "micro, small, and medium enterprises". An SME is defined as a small business that has more than 30 employees but less than 250 employees.

South Africa

In the National Small Business Amendment Act 2004,[18] micro-businesses in the different sectors, varying from the manufacturing to the retail sectors, are defined as businesses with five or fewer employees and a turnover of up to R100,000 ZAR ($6,900). Very small businesses employ between 6 and 20 employees, while small businesses employ between 21 and 50 employees. The upper limit for turnover in a small business varies from R1 million ($69,200) in the agricultural sector to R13 million ($899,800) in the catering, accommodations and other trade sectors as well as in the manufacturing sector, with a maximum of R32 million ($2,214,800) in the wholesale trade sector.

Medium-sized businesses usually employ up to 200 people (100 in the agricultural sector), and the maximum turnover varies from R5 million ($346,100) in the agricultural sector to R51 ($3,529,800) million in the manufacturing sector and R64 ($4,429,600) million in the wholesale trade, commercial agents and allied services sector.

A comprehensive definition of an SME in South Africa is, therefore, an enterprise with one or more of the following characteristics:

- Fewer than 200 employees,

- Annual turnover of less than R64 million,

- Capital assets of less than R10 million,

- Direct managerial involvement by owners[19]

Asia

SMEs account for nearly 90% of all company entities in developing Asian countries and are the principal private sector employers, supplying 50-80% of all jobs.[20]

SMEs cover 97-99% of all firms in South-east Asia, contributing considerably to each country's GDP—for example, 46% in Singapore, 57% in Indonesia, and over 40% in other nations.[20]

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, Bangladesh Bank defines Small and medium enterprises based on fixed asset, employed manpower and yearly turn over, and they are definitely not Public Limited Co. and requires these characteristics -

| Serial No | Sector | Fixed Asset other than Land and Building (Tk)

SE (Small Enterprises) & ME (Medium Enterprises) |

Employed Manpower | Yearly Turn Over (Tk)

(N/A-Not Applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Services | For SE 1000,000 - 200,00,000 &

For ME 200,00,000 - 30,00,00,000 |

SE - 16-50 & ME - 51-120 | N/A |

| 02 | Business | For SE 1000,000 - 200,00,000 | SE - 16-50 | SE 10,000,000-120,000,000 |

| 03 | Industrial | For SE 7,500,000 - 150,000,000

For Me 150,000,000 - 500,000,000 |

SE - 31-120 & ME - 121-300 | N/A |

Hong Kong

Hong Kong defines Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as any manufacturing business that employs less than 100 people or any non-manufacturing business that employs less than 50 people.[21]

98% of business establishments in Hong Kong are defined as SMEs and employed 45% of the work force.[21][22]

India

India defines Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises based on dual criteria of investment and turnover. This definition is provided in Section 7 of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises Development Act, 2006 (MSMED Act) and was notified in September 2006. The Act provides for the classification of enterprises based on their investment size and the nature of the activity undertaken by that enterprise. As per MSMED Act, enterprises are classified into two categories - manufacturing enterprises and service enterprises. For each of these categories, a definition is given to explain what constitutes a micro-enterprise or a small enterprise or a medium enterprise. If an enterprise does not fall under the above categories, it would be considered a large-scale enterprise.

In June 2020, India updated the definition as follows:

| Sr No | Classification | Criteria (in ₹) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Micro Enterprises | Investment <= 1 cr and Turnover <= 5 cr |

| 2 | Small Enterprises | Investment <= 10 cr and Turnover <= 50 cr |

| 3 | Medium Enterprises | Investment <= 50 cr and Turnover <= 250 cr |

Businesses that are declared as MSMEs and within specific sectors and criteria can then apply for "priority sector" lending to help with business expenses; banks have annual targets set by the Prime Minister's Task Force on MSMEs for year-on-year increases of lending to various categories of MSMEs.[23] MSME is considered a key contributor to India's growth and contributes 48% to India's total export.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the government defines micro, small, and medium enterprises (Indonesian: usaha mikro kecil menengah, UMKM) based on their assets and revenues according to Law No. 20/2008:[24]

| Type | Maximum assets, Rp | Gross Revenue, Rp | Number of Employee Statistics Indonesia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | maximum 50,000,000 | maximum 300,000,000 | 1-4 |

| Small | 50,000,000-500,000,000 | 300,000,000-2,500,000,000 | 5-9 |

| Medium | 500,000,000-10,000,000,000 | 2,500,000,000-50,000,000,000 | 20-99 |

| Large | >10,000,000,000 | >50,000,000,000 | >99 |

An annual revenue of Rp 50 billion is approximately equal to US$3.7 million as of November 2017.

Despite their significant contribution to GDP and job creation, Indonesian MSMEs confront a number of obstacles. One of the most significant is capital access: 60-70 percent of MSMEs lack access to financial institutions and their funding options. Other restrictions include inadequate infrastructure, difficulties acquiring company licences and permissions, high tax rates, political insecurity, and improving their brand image in the digital era. .[25] Companies nowadays utilise websites and social media platforms as strategic communication tools to communicate not only their company profiles, but also the products or services they offer to their target market. Therefore, examining the key roles of websites and social media in the formation of a brand's image is critical for firms to remain competitive in today's tight business environment. Companies can also combined between enhancing their website's quality and brand awareness. a successful brand awareness is when customers could recall and recognise the brand. Not only from websites that company could increase their brand awareness, social media could also increase brand awareness. If the company can deliver interesting and useful material, it may enhance interaction with its social media channels, resulting in increased consumer brand recognition.[26] Company could also have bigger potential to be funded by Bank Indonesia if the company could attract consumer either international or local.

Jakarta, as the capital city of Indonesia, there are 529 SMEs with the potential to be funded by Bank Indonesia. [27]

| Economy Sector | Number of Company, |

|---|---|

| Processing Industry | 151 |

| Health Services and Social Activities | 1 |

| Rental leasing services without option rights, employment, travel agents and other business support | 9 |

| Professional, Scientific And Technical Services | 11 |

| Other Service Activities | 21 |

| Arts, Entertainment And Recreation | 1 |

| Construction | 2 |

| Water Procurement, Waste Management And Recycling, Waste And Garbage Disposal And Cleaning | 1 |

| Provision of Accommodation and Provision of Food and Drink | 80 |

| Wholesale and retail trade of car and motorcycle repair and maintenance | 236 |

| Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries | 16 |

Philippines

According to the Department of Trade and Industry's 2020 List of Establishments report, there are 957,620 registered business enterprises operating in the country, composed of 99.51% MSMEs and 0.49% large firms. The MSMEs consist of 88.77% microenterprises, 10.25% small enterprises, and 0.49% medium enterprises. Among the top industry sectors include (1) wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (445,386); (2) accommodation and food service activities (134,046); (3) manufacturing (110,916); (4) other service activities (62,376); and (5) financial and insurance activities (45,558) which accounted for about 83.77% of the total number of MSME establishments. Prior to the pandemic, MSMEs generated more than 5.38 million jobs or 62.66% of the country's total employment with a 29.38% share from micro-enterprises followed by 25.78% and 7.50% for small and medium enterprises.[7]

Singapore

With effect from 1 April 2011, the definition of SMEs is businesses with annual sales turnover of not more than $100 million or employing no more than 200 staff.[28]

European Union

Small companies are important to the European economy as they account for 99.8% of non-financial enterprises in the European Union (EU) and employ two-thirds of the workforce in the EU.[29][30] The majority of European firms are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), employing over 100 million people. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a large majority of SMEs saw a decline in revenue during 2020-2021.[31][32][33][34]

The pandemic has had a greater impact on SMEs than on large businesses, with an average sales loss of 26% versus 23% for large businesses.[35][36] Government assistance appears to have benefited SMEs more than large corporations among the companies that do have overdraft facilities, indicating a successful application of policies to ease financial limitations for SMEs even when they receive help from the banking sector.[35][37] The EIB Group contributed more than €16.35 billion to small and medium-sized firms in 2022.[38]

SMEs were more quick in altering output during the pandemic, despite the intensity of the shock. In reaction to the crisis, one-third of major enterprises altered their output or services, compared to 37% of SMEs.[35][36]

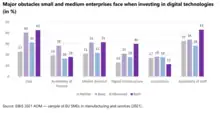

Large businesses, on the other hand, embraced digitization to a greater extent than small businesses, with 26% boosting their online distribution of products and services, compared to 22% for SMEs. The most significant difference in adaption measures was shown in the chance of expanding remote work, which increased by 25% among SMEs but 50% among large businesses.[35][39]

The criteria for defining the size of a business differ from country to country, with many countries having programs of business rate reduction and financial subsidy for SMEs. According to the European Commission,[40] SMEs are enterprises which meet the following definition of staff headcount and either the turnover or balance sheet total definitions:

| Company category | Staff headcount | Turnover | Balance sheet total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-sized | < 250 | ≤ €50 million | ≤ €43 million |

| Small | < 50 | ≤ €10 million | ≤ €10 million |

| Micro | < 10 | ≤ €2 million | ≤ €2 million |

In July 2011, the European Commission said it would open a consultation on the definition of SMEs in 2012. A consultation document was issued on 6 February 2018 and the consultation period closed on 6 May 2018. As of November 2019, no conclusions or responses have yet emerged.[41]

In Europe, there are three broad parameters that define SMEs:

- Micro-enterprises have up to 10 employees

- Small enterprises have up to 50 employees

- Medium-sized enterprises have up to 250 employees.[42]

The European definition of SME follows: "The category of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is made up of enterprises which employ fewer than 250 persons and which have an annual turnover not exceeding 50 million euro, and/or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding 43 million euro."[43] In order to prepare for an evaluation and revision of some features of the small and medium-sized enterprises definition European Union established public consultation period from 6 February 2018 to 6 May 2018. Public consultation is available for all EU member country citizens and organizations. Especially, national and regional authorities, enterprises, business associations or organizations, venture capital providers, research and academic institutions, and individual citizens are expected as the main contributors.[44]

EU member states have had individual definitions of what constitutes an SME. For example, the definition in Germany had a limit of 255 employees, while in Belgium it could have been 100. The result is that while a Belgian business of 249 employees would be taxed at full rate in Belgium, it would nevertheless be eligible for SME subsidy under a European-labelled programme.

SMEs are a crucial element in the supplier network of large enterprises which are already on their way towards Industry 4.0.[45] According to German economist Hans-Heinrich Bass, "empirical research on SME as well as policies to promote SME have a long tradition in [West] Germany, dating back into the 19th century. Until the mid-20th century, most researchers considered SME as an impediment to further economic development and SME policies were thus designed in the framework of social policies. Only the Ordoliberalism school, the founding fathers of Germany's social market economy, discovered their strengths, considered SME as a solution to mid-20th century economic problems (mass unemployment, abuse of economic power), and laid the foundations for non-selective (functional) industrial policies to promote SMEs."[46] Only around 20% of European SMEs are substantially digitalized, compared to almost 50% of major businesses.[29][47] Small and medium-sized companies make up 56.2% of the non-financial sector.

Smaller companies account for more than 60% of the value contributed to the non-financial sector in Belgium, Italy, and Spain, three of the nations worst hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.[29][48] An estimated 50% of Europe's small firms may fail because they lack the substantial financial reserves required to weather the crisis.[29][49]

With around 338,000 functioning in Bulgaria in 2022, SMEs and mid-caps are major contributors in the Bulgarian economy. They also employ over 75% of the workforce and create 65% of the economy's added value.[50][51][52][53]

The results of an EU survey conducted in 2021 suggest that during the pandemic, in countries with larger fiscal packages, SMEs were on average more likely to experience bankruptcy even after controlling for the size of the shock, the use of bank financing, and country and sector fixed effects. When policy assistance rises by 1% of GDP, the probabilities of bankruptcy for a SME are 2.7 times higher than for a non-SME.[35][54] Credit limitations are especially difficult for SMEs and new businesses to overcome. Credit constraints affect 24% of SMEs and 27% of young businesses.[35]

Poland

The SME sector in Poland generates almost 50% of the GDP, and out of that, for instance, in 2011, micro companies generated 29.6%, small companies 7.7%, and medium companies 10.4% (big companies 24.0%; other entities 16.5%, and revenues from customs duties and taxes generated 11.9%). In 2011, out of the total of 1,784,603 entities operating in Poland, merely 3,189 were classified as "large", so 1,781,414 were micro, small, or medium. SMEs employed 6.3 million people out of the total of 9.0 million of labour employed in the private sector. In Poland in 2011 there were 36.2 SMEs per 1,000 inhabitants.[55]

Nearly seven million people are employed by small businesses in Poland, which accounts for around half of the country's GDP, yet smaller businesses are less likely than larger ones to invest in strategies to combat climate change or boost energy efficiency. In October 2021, the Bank Ochrony rodowiska, a Polish bank that specializes in funding environmental protection initiatives received €75 million from the European Investment Bank (EIB) for these small enterprises.[56]

The Polish bank wants to use at least 50% of the loan for initiatives with a clear emphasis on tackling climate change, such improving building energy efficiency or turning to renewable energy sources like solar power. The money is set to be distributed across Poland, with around 80% of it projected to go to cohesive regions.[56]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom (UK), a company is defined as being an SME if it meets two out of three criteria: it has a turnover of less than £25m, it has fewer than 250 employees, it has gross assets of less than £12.5m.[57] Very small companies are called in the UK micro-entities, which have simpler financial reporting requirements. Such micro-enterprises must meet any two of the following criteria: balance sheet £316,000 or less; turnover £632,000 or less; employees 10 or less.[58]

Many small and medium-sized businesses form part of the UK's currently growing Mittelstand, or Brittelstand as it is also sometimes named.[59] These are businesses in Britain that are not only small or medium but also have a much broader set of values and more elastic definition.

The Department for Business Innovation and Skills estimated that at the start of 2014, 99.3% of UK private sector businesses were SMEs, with their £1.6 trillion annual turnover accounting for 47% of private sector turnover.[60][61]

In order to support SMEs, the UK government set a target in 2010 "that 25% of government’s spend, either directly or in supply chains, goes to SMEs by 2015"; it achieved this by 2013.[62]

Norway

In Norway it is normal to design small and medium-sized businesses as businesses with less than 100 employees. Businesses with 1-20 employees are defined as small, while businesses with 21-100 employees are considered medium-sized. Businesses with more than 100 employees would be considered a big business. Micro-sized businesses is a little used expression in Norway.NHO

Small and medium-sized businesses make up more than 99% of all businsesses in Norway, and together they employ 47% of all employees in the private sector. Together, SMEs account for 44% of the economic value added each year - almost 700 billion Norwegian Kroners (NOK).Fakta om små og mellomstore bedrifter (SMB)

Switzerland

In Switzerland, the Federal Statistical Office defines small and medium-sized enterprises as companies with less than 250 employees.[63] The categories are the following:[63]

- Microentreprises: 1 to 9 employees

- Small enterprises: 10 to 49 employees

- Medium-sized enterprises: 50 to 249 employees

- Large enterprises: 250 employees or more

Canada

Industry Canada defines a small business as one with fewer than 100 paid employees, and a medium-sized business as one with at least 100 and fewer than 500 employees. As of December 2012, there were 1,107,540 employer businesses in Canada of the rally . Canadian controlled private corporations receive a 17% reduction in the tax rate on taxable income from active businesses up to $500,000. This small business deduction is reduced for corporations whose taxable capital exceeds $10M and is eliminated for corporations whose taxable capital exceeds $15M.[64] It has been estimated that almost $2 trillion of Canadian SMEs will be coming up for sale over the next decade, which is twice as large as the assets of the top 1,000 Canadian pension plans and approximately the same size as Canadian annual GDP.[65]

Mexico

The small and medium-sized companies in Mexico are called PYMEs, which is a direct translation of SMEs. But there's another categorization in the country called MiPyMEs. The MiPyMEs are micro, small and medium-sized businesses, with an emphasis on micro which are one man companies or a type of freelance.

| Sector/Size | Industrial | Commerce | Services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | 0-10 | 0-10 | 0-10 |

| Small | 11-50 | 11-30 | 11-50 |

| Medium | 51-250 | 31-100 | 51-100 |

United States

In the United States, the Small Business Administration sets small business criteria based on industry, ownership structure, revenue and number of employees (which in some circumstances may be as high as 1500, although the cap is typically 500).[67] Both the US and the EU generally use the same threshold of fewer than 10 employees for small offices (SOHO).

Australia

In Australia, a SME has 200 or fewer employees. Micro Businesses have 1–4 employees, small businesses 5–19, medium businesses 20–199, and large businesses 200+.[68] Australian SMEs make up 98% of all Australian businesses, produce one-third of total GDP, and employ 4.7 million people. SMEs represent 90 percent of all goods exporters and over 60% of services exporters.[69]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, 99% of businesses employ 50 or less staff, and the official definition of a small business is one with 19 or fewer employees.[70][71] It is estimated that approximately 28% of New Zealand's gross domestic product is produced by companies with fewer than 20 employees.[72]

See also

- Confédération Européenne des Associations de Petites et Moyennes Entreprises (CEA-PME), an international federation of SME associations

- Environmental regulation of small and medium enterprises

- Hidden champions

- Mittelstand

- Small and medium enterprises in Mexico

- Small business

References

-

Compare:

Fischer, Eileen; Reuber, Rebecca (2000). Industrial Clusters and SME Promotion in Developing Countries. Issue 3 of Commonwealth trade and enterprise paper, ISSN 2310-1369. London: Commonwealth Secretariat. p. 1. ISBN 9780850926484. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

In most countries, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) make up the majority of businesses and account for the highest proportion of employment.

- Olorunshola, Damilola Temitope; Odeyemi, Temitayo Isaac (2022-01-01). "Virtue or vice? Public policies and Nigerian entrepreneurial venture performance". Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. 30: 100–119. doi:10.1108/JSBED-07-2021-0279. ISSN 1462-6004. S2CID 249721896.

- "Chile", Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2016, Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs, OECD Publishing, 2016-04-14, pp. 155–173, doi:10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2016-11-en, ISBN 9789264249462, retrieved 2018-10-01

- Rijkers et al (2014): "Which firms create the most jobs in developing countries?", Labour Economics, Volume 31, December 2014, pp.84–102

-

United States. Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba (2004). Report to the President. Department of State publication, volume 11164. Colin L. Powell. U.S. Department of State. p. 233. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

In the United States, small business accounts for 50 percent of jobs, 40 percent of GDP, 30 percent of exports, and one-half of technological innovations.

-

Compare:

Antoldi, Fabio; Cerrato, Daniele; Depperu, Donatella (5 January 2012). Export Consortia in Developing Countries: Successful Management of Cooperation Among SMEs. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media (published 2012). p. v. ISBN 9783642248788. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are highly significant in both developed and developing countries as a proportion of the totl number of firms, for the contribution they make to employment, and for their ability to develop innovation.

- Cueto, L. J.; Frisnedi, A. F. D.; Collera, R. B.; Batac, K. I. T.; Agaton, C. B. (2022). "Digital Innovations in MSMEs during Economic Disruptions: Experiences and Challenges of Young Entrepreneurs". Administrative Sciences. 12 (1): 8. doi:10.3390/admsci12010008. ISSN 2076-3387.

- Aga et al. (2015): SMEs, Age, and Jobs: A Review of the Literature, Metrics, and Evidence, World Bank Group, November 2015.

- P.E. Petrakis, P.C. Kostis (2012), "The Role of Knowledge and Trust in SMEs", Journal of the Knowledge Economy, DOI: 10.1007/s13132-012-0115-6.

- Kushnir (2010) A Universal Definition of Small Enterprise: A Procrustean bed for SMEs?, World Bank

- Gibson, T.; van der Vaart, H.J. (2008): Defining SMEs: A Less Imperfect Way of Defining Small and Medium Enterprises in Developing Countries", Brookings Institution website, September 2008

- Finance in Africa: for green, smart and inclusive private sector development. European Investment Bank. 2021-11-18. ISBN 978-92-861-5063-0.

- "Finance in Africa: for green, smart and inclusive private sector development". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- "MSME Finance Gap". SME Finance Forum. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- "Eliminating Gender Disparities in Business Performance in Africa: Supporting Women-Owned Firms". World Bank. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- "World Bank SME Finance: Development news, research, data". World Bank. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- Central Bank Of Nigeria (March 30, 2010). "N200 BILLION SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES CREDIT GUARANTEE SCHEME(SMECGS)" (PDF). Central Bank of Nigeria. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- "Republic of South Africa, National Small Business Amendment Act" (PDF). www.thedti.gov.za. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- Du Toit.Erasmus.& Strydom "Definition of small business" Introduction to business management, 7th Edition Oxford University Press,2009, p. 49

- Nguyen, Lan Thanh; Su, Jen-Je; Sharma, Parmendra (21 June 2019). "SME credit constraints in Asia's rising economic star: fresh empirical evidence from Vietnam". Applied Economics. 51 (29): 3170–3183. doi:10.1080/00036846.2019.1569196. hdl:10072/384003. ISSN 0003-6846.

- "Small and medium enterprises (SME)". Support and Consultation Centre for SMEs, Trade and Industry Department (Hong Kong). 2022-07-20. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- "Support to Small and Medium Enterprises". Trade and Industry Department (Hong Kong). 2022-08-02. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- "Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises". Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "Indonesian Government Law No. 20 of 2008" (PDF). Commission for the Supervision of Business Competition. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Torm, Nina (September 2020). "To what extent is social security spending associated with enhanced firm‐level performance? A case study of SMEs in Indonesia". International Labour Review. 159 (3): 339–366. doi:10.1111/ilr.12155. ISSN 0020-7780.

- Suryani, Tatik-; Fauzi, Abu Amar; Nurhadi, Mochamad (14 August 2021). "Enhancing Brand Image in the Digital Era: Evidence from Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) in Indonesia". Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business. 23 (3): 314–340. doi:10.22146/gamaijb.51886. ISSN 2338-7238.

- "Database UMKM". www.bi.go.id.

- "Fact Sheet on New SME Definition" (PDF).

- "Digital innovation hubs to the rescue". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- Anonymous (2016-07-05). "Entrepreneurship and Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)". Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs - European Commission. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- Bank, European Investment (2022-01-27). EIB Activity Report 2021. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5108-8.

- "Small and medium-sized enterprises | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- "Two companies empower small businesses and grow together". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- "Europe's Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, Start-ups…". Renew Europe. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- Bank, European Investment (2022-05-18). Business resilience in the pandemic and beyond: Adaptation, innovation, financing and climate action from Eastern Europe to Central Asia. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5086-9.

- "Home". www.oecd-ilibrary.org. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- "Financing the economy - SMEs, banks and capital markets". European Central Bank - Banking supervision. 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- "Slovak high tech metallurgy business booms with EU financing". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- "Productivity gains from teleworking in the post COVID-19 era: How can public policies make it happen?". OECD. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- "What is an SME? - Small and medium sized enterprises (SME) - Enterprise and Industry". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - European Commission, Public consultation on the review of the SME definition, accessed 22 November 2019

- European Commission (2003-05-06). "Recommendation 2003/361/EC: SME Definition". Archived from the original on 2015-02-08. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- Enterprise and Industry Publications: The new SME definition, user guide and model declaration, Extract of Article 2 of the Annex of Recommendation 2003/361/EC

- "Consultations". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- Sommer, Lutz (28 November 2015). "Industrial revolution - industry 4.0: Are German manufacturing SMEs the first victims of this revolution?". Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management. 8 (5). doi:10.3926/jiem.1470.

- Hans-Heinrich Bass: KMU in der deutschen Volkswirtschaft: Vergangenheit, Gegenwart, Zukunft, Berichte aus dem Weltwirtschaftlichen Colloquium der Universität Bremen Nr. 101, Bremen 2006 Archived 2017-12-15 at the Wayback Machine (PDF; 96 kB)

- "Small and medium-sized enterprises: an overview". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- "Small and medium-sized enterprises: an overview". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19): SME policy responses". OECD. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- "More than 75% of employees in Bulgaria work in small and medium-sized enterprises ● Ministry of Economy and Industry". www.mi.government.bg. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. "Supporting SMEs in Bulgaria". PwC. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- "EBRD financing to support Bulgarian firms affected by war on Ukraine". www.ebrd.com. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- "Seeds of growth". eib.org.

- Dörr, Julian Oliver; Licht, Georg; Murmann, Simona (2022-02-01). "Small firms and the COVID-19 insolvency gap". Small Business Economics. 58 (2): 887–917. doi:10.1007/s11187-021-00514-4. ISSN 1573-0913. PMC 8258278.

- D. Walczak, G. Voss, New Possibilities of Supporting Polish SMEs within the Jeremie Initiative Managed by BGK, Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, Vol 4, No 9, p. 760-761.

- "EIB Group Activities in EU cohesion regions in 2021". www.eib.org. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- "Mid-sized businesses". gov.uk. Department of Business, Innovation and Skills. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Micro-entities, small and dormant companies". GOV.UK.

- Groom, Brian (1 October 2015). "Brittelstand stymied by lack of growth and skills". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Bridging loans UK can be used for many purposes". www.konnectfinancial.co.uk. Konnect Financial. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- "Statistical Release: Business Population Estimates for the UK and Regions 2014" (PDF). Department for Business Innovation and Skills. 26 November 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "2010 to 2015 government policy: government buying". 20 February 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- (in French) Taille, forme juridique, secteurs, répartition régionale, Swiss Federal Statistical Office (page visited on 24 October 2017).

- "T2 Corporation - Income Tax Guide - Chapter 4: Page 4 of the T2 return". Canada Revenue Agency. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- "Equicapita May 2014 - Who Will Buy Baby Boomer Businesses?" (PDF).

- Ley para el Desarrollo de la Competitividad de la Micro, Pequeña y Mediana Empresa

- United States Small Business Administration. "Size Standards". Retrieved 2023-09-21.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "1321.0 - Small Business in Australia, 2001". 23 October 2002. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "AN INTRODUCTION TO FTAs (FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS)" (PDF). Small Business Association of Australia, 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2014). "The Small Business Sector Report 2014" (PDF). Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. MBIE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-12.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "SMEs in New Zealand: Structure and Dynamics 2011", Page 10-11, Ministry of Economic Development

- "Archived copy" (PDF). www.mbie.govt.nz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-10. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)