Yoon Mee-hyang

Yoon Mee-hyang (Korean: 윤미향; Hanja: 尹美香; born 1964) is a South Korean human rights activist, politician, and author. She was the former head of the Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, an organization dedicated to advocacy for former comfort women, who were forced into sexual slavery during World War II. She is the author of 25 Years of Wednesdays: The Story of the "Comfort Women" and the Wednesday Demonstrations.

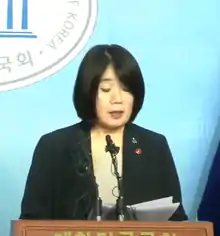

Yoon Mee-hyang | |

|---|---|

| 윤미향 | |

| |

| Member of the National Assembly | |

| Assumed office May 30, 2020 | |

| Constituency | Proportional representation |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 23, 1964 Namhae County, South Gyeongsang Province, South Korea |

| Political party | Democratic Party of Korea (2020-present) |

| Other political affiliations | Platform Party (2020) |

| Spouse | Kim Sam-seok |

| Alma mater | Hanshin University Ewha Womans University |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Yun Mi-hyang |

| McCune–Reischauer | Yun Mihyang |

In April 2020, Yoon was elected to National Assembly of the Republic of Korea, in a seat allocated by proportional representation.[1]

In September 2020 Yoon was suspended from the Democratic Party after being indicted by the Seoul Western District Prosecutors’ Office on eight charges including fraud, embezzlement and breach of trust for misappropriating donations and government subsidies from the comfort women advocacy organization she was leading.[2]

Education

Yoon was born in Namhae, South Gyeongsang Province, in 1964.[3] She graduated from Hanshin University in 1987 and earned a master's degree in social welfare from Ewha Womans University in 2007.[4][5]

Advocacy

Since the 1990s, Yoon has been a leader of the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, now called the Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan.[6][7][8][9] The organization was established in 1990 to advocate for the rights of former comfort women.[6] Since January 1992, the council has organized over 1000 weekly rallies in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul to raise awareness of the issue of war violence against women.[6][10][11] The group has called upon the Japanese government to issue a formal apology and compensation to former comfort women.[12]

Yoon's book on the subject, 20 Years of Wednesdays: The Unshakable Hope of the Halmoni - Former Japanese Military Comfort Women (Korean: 20년간의 수요일 : 일본군 '위안부' 할머니들이 외치는 당당한 희망), was published in 2010 in Korean, and translated into Japanese the following year.[13][14] A 2016 follow-up, 25 Years of Wednesdays (Korean: 25 년간의 수요일), included information on the new agreement between the Korean and Japanese governments to peacefully resolve the issue.[15] An English translation by Koeun Lee was published in 2019.[16]

Yoon established the War and Women's Human Rights Museum in Seoul in 2012.[6][10] She has also served as a founding member of the Korea Women's Foundation and as executive director of the Women's Subcommittee of the National Reunification Movement.[5] Yoon appears in The Apology, a documentary film directed by Tiffany Hsiung and featuring former comfort women Gil Won-Ok, Adela Reyes Barroquillo, and Cao Hei Mao.[17]

Election

On April 15, 2020, Yoon was elected to a proportional representation National Assembly seat as a candidate of the Platform Party, a satellite party of the Democratic Party of Korea.[18]

Controversy

In May 2020, Lee Yong-soo, a 91 year old comfort woman survivor, accused Yoon of not using the public donations to benefit the comfort women victims.[19] In a press conference, Lee Yong-soo accused Yoon and her organization of financially and politically exploiting the survivors for 30 years.[20] Lee also stated that Yoon “must not become a member of the National Assembly. She must first solve this problem.” Lee stated she did not support Yoon's parliamentary candidacy and accused Yoon of lying about having her support during the election.[21]

The Democratic Party of Korea suspended the party membership of Rep. Yoon Mee-hyang, who became a proportional lawmaker based on her career of supporting comfort women survivors.[22]

Awards and honours

In 2012, Yoon was awarded the 9th annual Seoul Women's Award.[23]

In 2013, Yoon was awarded the Late Spring Unification Award, given to individuals who have contributed to national reconciliation and reunification.[4] The same year, she was named a co-winner of Hanshin University's Hanshin Prize, given to individuals for their outstanding contributions to society.[10]

References

- "[선택 2020] 거리에서 '수요집회' 이끌던 윤미향, 이제는 국회로". 뉴스핌 (in Korean). 2020-04-16. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- MYO-JA, SER (September 16, 2020). "Yoon Mee-hyang suspended from Democratic Party".

- Whee Hee-bok (2016-01-11). "[원희복의 인물탐구]한국정신대대책협의회 윤미향 상임대표… 24년간 작은 함성, 세계로 증폭되다". 주간경향 (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Kim Mi-ran (2013-04-01). "정대협 윤미향 대표…18번째 '늦봄 통일상' 수상자 - 고발뉴스닷컴". Gobal News (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Kim, Dong-Gyu (2015-09-25). "제9회 의암주논개상에 정신대대책협 윤미향 대표 선정". News1 Korea (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Kambayashi, Takehiko (2014-09-05). "Yoon Mee-hyang helps Korea's World War II sex slaves tell their stories". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- "Readout of the Secretary-General's meeting with Ms. Yoon Mee-Hyang, Co-Chair and Representative for the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, and Ms. Gil Won-ok, one of the victims". United Nations Secretary-General. 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Lee Tae-hee (2019-01-28). "Former 'comfort woman' dies at 93, leaving 24 survivors". The Korean Herald. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Sang-Hun, Choe (2019-01-29). "Kim Bok-dong, Wartime Sex Slave Who Sought Reparations for Koreans, Dies at 92". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Song A-young (2013-04-06). "올해 한신상 수상자에 '김해성 목사·윤미향 대표'". 한국대학신문 (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Lee Minji (2020-01-08). "After 28 years, rally protesting Japan's wartime sex slavery still going strong". Yonhap News Agency. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Yun-hyung, Gil (2014-11-23). "This is not just a statue of a young girl, but a monument to peace". english.hani.co.kr. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Heo Yeon (20 September 2011). "위안부문제 다룬 책, 일본 권장도서 됐다". 매일경제 (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Nishino, Rumiko; Kim, Puja; Onozawa, Akane, eds. (2018). Denying the Comfort Women: The Japanese State's Assault on Historical Truth. Abingdom, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-04871-3. OCLC 1020709510.

- Kim Se-jeong (2016-01-24). "Activist publishes book on former sex slave victims". The Korea Times. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Yoon, Mee-hyang (2019). 25 Years of Wednesdays: The Story of the "Comfort Women" and the Wednesday Demonstrations. Translated by Lee, Koeun (First English ed.). Seoul: Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan. ISBN 979-11-88835-08-9. OCLC 1133655622.

- National Film Board of Canada, The Apology, retrieved 2020-03-22

- "'윤봉길 손녀' 윤주경·'4부자 의원' 김홍걸·'수요집회' 윤미향 당선". Seoul Newspaper (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- "Yoon uses comfort women for own interest". koreatimes. 25 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Min-joong, Kim; Myo-ja, Ser (June 1, 2020). "Civic group backs allegations against Yoon Mee-hyang". Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Shim, Elizabeth (May 7, 2020). "Ex-South Korea comfort woman accuses activist of exploiting women, funds". UPI. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- SER, MYO-JA (September 16, 2020). "Yoon Mee-hyang suspended from Democratic Party".

- "윤미향 상임대표, 서울시여성상 대상 수상". 여성신문 (in Korean). 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2020-03-22.